Learning without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous. Confucius, Chinese philosopher. From Analects (Book II, Chapter XV).

Shall I tell you the secret of the true scholar? It is this: Every man I meet is my master in some point, and in that I learn of him.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson, American essayist. From Letters and Social Aims: Greatness.

It is demonstrable that many of the obstacles to change which have been attributed to human nature are in fact due to the inertia of institutions and to the voluntary desire of powerful classes to maintain the existing status. John Dewey (1859 to 1952), American philosopher and educator. From Monthly Review (March 1950).

TYPES OF INTERACTIONS

Despite the rather pessimistic comments of John Dewey above, both academic and industrial institutions are recognizing the many benefits that can be derived from active collaboration. This is generally viewed as a positive trend with potentially important benefits to both. The industrial-academic relationship may be viewed from several perspectives, including that of the government and public sectors, in addition to the more obvious perspectives of pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions.

There is no doubt that industrial-academic relationships in the United States are increasing both in extent and importance. One of the major reasons for this change relates to the decrease in unsponsored research funds (e.g., from National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, foundations) available per academic scientist. This has led many scientists, departments, and even entire medical schools to pursue opportunities and relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical companies benefit from university expertise, and universities are paid for their time and effort. University scientists and clinicians also benefit scientifically, career wise, and in other ways by working on important projects (

Sterman 1989).

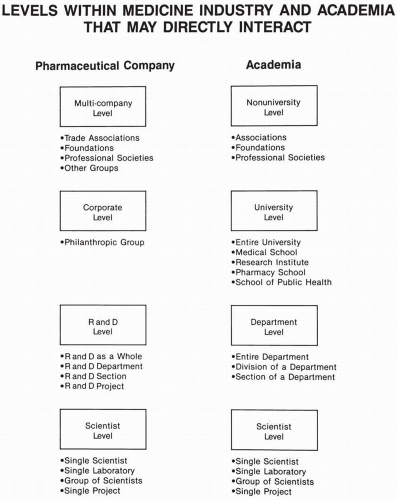

There are many types of interactions between pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions. As indicated in

Table 31.1, these interactions may be viewed from either the academic or the pharmaceutical company’s perspective. Few companies utilize all of these approaches, and the nature and degree of interactions vary greatly. Relationships are established between a pharmaceutical company and an academic institution (

Table 31.2), between a pharmaceutical company and individual

academic scientists, or both.

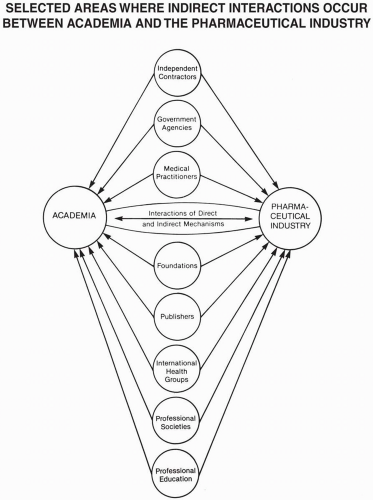

Figure 31.1 illustrates the numerous levels within companies and academic institutions at which interactions occur. An important point of this figure is that interactions may occur across different levels as well as across the same level. Some areas where indirect interactions occur are shown in

Fig. 31.2. A number of the possible relationships and interactions are described in the following sections.

Four Types of Relationships

Short-term grants targeted to scientific or clinical questions where in-house resources are unavailable or unsuitable to address the question. These grants may or may not be renewable. The terms and funding are strictly negotiated to secure the objective. An academic scientist may obtain equipment or staff to assist with conducting his or her research.

Unrestricted grants without any conditions except for the goal of enhancing knowledge. The company may view this grant as providing an entree into the institution, as a possible future recruitment exercise, or as a public relations exercise to improve the corporate image. These grants are usually limited to a single year, but the contract may include terms for renewing the grant.

Major alliances between academic and pharmaceutical groups are discussed further in various chapters in this book.

Ideas for New Drugs

Companies solicit and/or accept ideas from people and groups in academia. A company that establishes products in a new therapeutic area is usually approached on a frequent basis by academicians and others with novel ideas. For example, after the Burroughs Wellcome Company introduced some antiviral drugs, numerous individuals and groups began to approach the company with novel ideas relating to antiviral products. Even if a newly marketed product does

not generate large sales revenue, it may establish a company’s reputation in a therapeutic area that will attract novel ideas and proposals with greater commercial potential. In addition, a company may solicit an academician to do a study on a marketed drug because the company does not want the regulatory responsibilities. The company may or may not provide sufficient funding to allow the academician to comply with his or her regulatory obligations as a sponsor-investigator if an Investigational New Drug Application (

IND) is required.

Conducting Research in Academic Institutions

The ability of most mid- and large-sized companies to conduct all relevant research activities “in-house” is often limited by space and resources (both skilled manpower and specialized equipment) rather than financial resources. Collaboration with academic scientists offers the potential for a company to expand its capabilities on a temporary basis to probe and hopefully answer specific research questions. Collaboration with academicians also allows a company to pursue research in areas where (a) it may supplement its strengths, (b) it is currently weak, or (c) it is not currently active.

Companies sometimes invest or donate large sums of money to help finance an institution, medical department, or scientific group. Benefits desired by the company are usually defined in terms of services and outputs (e.g., compounds, licensing rights) resulting from the institution’s scientists. Many opportunities exist for collaboration between companies and external scientists, institutes, and other groups who are well respected and who offer an opportunity for expanding drug discovery or research.

Several different types of relationships exist for research activities conducted in academic institutions:

Contract research performed by academicians for a pharmaceutical company

Research where a company has the right of first refusal for licensing any outputs (e.g., discoveries) with commercial value

Research sponsored by a company with the institution without the academicians having any special relationship with the sponsor

Research conducted by academicians with a new drug or marketed drug supplied by a company

Research conducted by pharmaceutical company personnel who also have an academic appointment

Research conducted jointly by academicians and pharmaceutical company personnel

These relationships, along with others described in this chapter, may be initiated either by the academic or pharmaceutical institution. If the academic group seeks to contact a pharmaceutical company, they may contact individual scientists, research and development executives, a business development department, a licensing group, or a new products group in marketing. Industry people may contact comparable people in an academic institution to initiate one of the previously discussed relationships.

Conducting Research in a Pharmaceutical Company

Pharmaceutical companies can biologically test compounds synthesized by outside (i.e., academic) scientists, who are given funds to support their work. There are a number of academic institutions that are screening compounds with high throughput screening methodologies and their “hits” may be followed up within industry with more sophisticated biological screens. Companies also conduct research jointly with academicians. This is often the result of an academician approaching the company with a novel idea. Sometimes, the company wants the academician to run a “pilot” study to see if it works before the company invests a substantial amount of money.