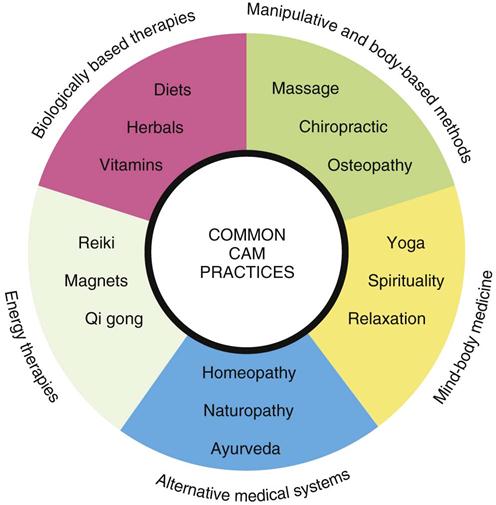

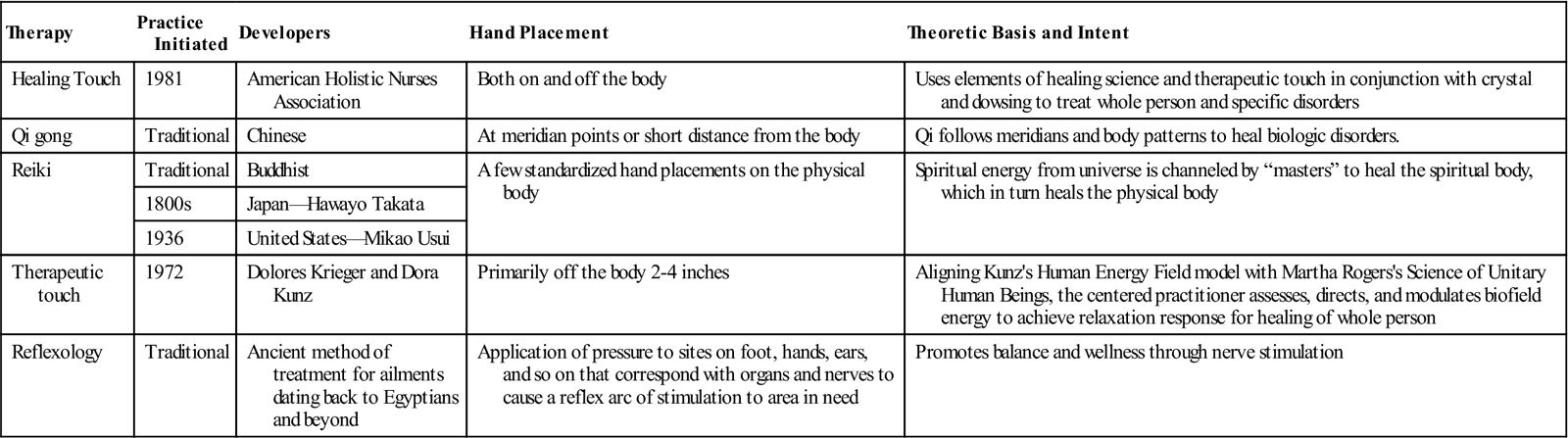

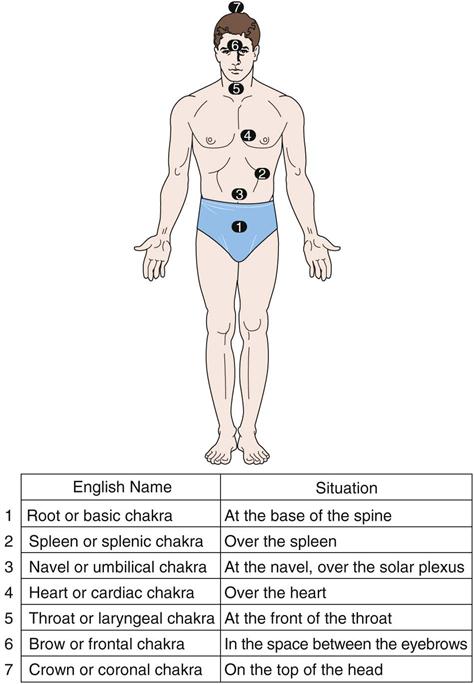

Rachael Larner An accurate presentation of the history of medicine in the United States needs to include influences from the botanic cultural traditions of Asia, India, Europe, and the First Nations. Our current medical system, referred to as biomedicine, began to dominate sometime in the mid-1800s with the discovery that microorganisms were responsible for disease and pathologic damage and that antitoxins and vaccines could improve the body’s ability to oppose the effects of pathogens. Armed with this knowledge, scientists and clinicians were able to refine surgical procedures and treat previously serious and fatal infections. As biomedicine dominated the healthcare system, it became the mainstream or “conventional” approach, establishing the standards for diagnosis and treatment of illness. By the 1990s, however, consumer faith and trust in this system began to falter, and many Americans sought complementary or alternative treatments for their healthcare. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), known currently as “integrative health practices,” has grown to constitute a significant percentage of American healthcare dollars and visits. This growth is sustained by patients who desire to be more empowered healthcare consumers and the availability of media information about the many alternatives to mainstream, conventional Western biomedical approaches to healthcare. Myths and misconceptions initially prevented investigation and development of promising therapies outside the biomedical regimen. In response to growing consumer pressure, anecdotal evidence, and a small body of published scientific results, the U.S. Congress established the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) within the office of the director, National Institutes of Health (NIH), in 1992. This office was given responsibility for: (1) facilitating fair, scientific evaluation of alternative therapies that showed promise in health promotion, and (2) reducing barriers to the acceptance and utilization of those alternative therapies that showed promise. In 1998 the OAM became the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, 2012a). This expansion into a center allowed more substantial funding for and initiation of research projects, providing more sound information about integrative health practices. The annual budget for NCCAM has grown significantly, as has the sophistication of research designs of studies being funded by the center. The NCCAM adheres to guidelines set forth in public policy. Many integrative health practices and therapies stem from a philosophy of wholeness, with intent to treat the entire person (body-mind-spirit) (Evidence for Practice). This is in contrast to the current gold standard of randomized, controlled clinical trials, which may not be the best, or indeed appropriate, way to measure the effectiveness of many integrative health practices and therapies. Conventional scientists and physicians and the proponents of integrative health practices and CAM often debate the appropriate forms of research to determine efficacy and safety of alternative therapies. A reason for this disparity stems from divergent theoretic models. The comprehensive approach takes into account multidimensional factors that may not easily or appropriately be studied independently. The comprehensive approach is more congruent with the philosophic underpinnings of most integrative health practices and CAM. The biomedical approach, on the other hand, is concerned with a disease orientation, suggesting that a specific agent or variable is responsible for a specific disorder or illness. The NCCAM has categorized the many integrative health practice modalities into five major domains: alternative medical systems, mind-body medicine, biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based methods, and energy therapies (Figure 30-1). Numerous treatments and systems are within each category. The remainder of this chapter discusses the major domains and provides examples of each. An estimated 10% to 30% of human healthcare is delivered by practitioners such as surgeons and nurses who have been trained in the mainstream, conventional Western biomedical model. The remaining 70% to 90% involves care given in a healthcare system that is based on alternative traditions—self-care based in folk practice or practices that range somewhere between alternative and traditional healthcare. Many of these integrative health therapies are culturally, ethnically, spiritually, or religiously derived. Among the diverse values, beliefs, and practices found in the many cultural groups in the United States are those relating to health, illness, professional healthcare, and folk healthcare (Box 30-1). They include well-known and respected Asian systems of medicine. Many Asian medicine techniques or systems are widely known in the United States. The most well-known and popular of these include herbal medicines, massage, energy therapy, acupressure, acupuncture, and qi gong (Figure 30-2). This integrative, alternative medicine system has a wide range of applications from health promotion to the treatment of illness. A significant aspect of Asian medicine is an emphasis on diagnosing and treating disturbances of qi (pronounced “chee”), or vital energy, and restoring its proper balance (Micozzi, 2010). Ayurveda is a traditional system from India that strives to restore the innate harmony of the individual while placing equal emphasis on body, mind, and spirit. Ayurvedic practitioners use many products and techniques to cleanse the body and restore balance. Key foundations are universal connectedness (e.g., that all living and nonliving things are joined together, health will be good if one’s mind and body are in harmony, disease arises when a person is out of harmony with the universe), the body’s constitution or prakriti (e.g., the person’s unique physical and psychologic characteristics and how the person functions to maintain health), and life forces, or doshas. Each person has a combination of three doshas; each dosha has a particular relationship with a bodily function and can be upset for a variety of reasons. Treatment is tailored to each person’s constitution and predominant dosha. Practitioners expect patients to be active participants because many ayurvedic treatments require changes in diet, lifestyle, and habits (NCCAM, 2012b). Native American, Middle Eastern, Tibetan, Central and South American, and African cultures have developed other traditional medical systems (Micozzi, 2010). Additional examples of complete integrative health practice and alternative medicine systems are naturopathic and homeopathic medicine systems. Homeopathic medicine is based on the principle that “like cures like” (i.e., a substance that in large doses produces the symptoms of a disease will, in a very diluted dose, cure the patient). Small doses of plant extracts and minerals specially prepared are given to stimulate the body’s defense mechanisms and encourage healing processes. Careful evaluation of symptoms enables the practitioner to determine a patient’s specific sensitivity and to select the appropriate remedy. Naturopathic medicine is one of the most recent alternative approaches to have developed as a health system across North America. In practice, modern naturopathic is eclectic, drawing on different systems and models (e.g., Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and manual therapies) to fit the patient profile and clinical problem with the appropriate techniques (Micozzi, 2010). Naturopathic medicine emphasizes health restoration as well as disease treatment based on the belief that disease is a manifestation of alterations in the body’s natural healing processes. Naturopathic physicians use multiple modalities, including clinical nutrition and diet; acupuncture; herbal medicine; homeopathy; spinal and soft tissue manipulation; physical therapies involving ultrasound, light, and electric currents; therapeutic counseling; and pharmacology (Pizzorno and Snider, 2010). A growing scientific movement has explored the mind’s ability to affect the body. The clinical application of this relationship is categorized as mind-body medicine. Some mind-body interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy), formerly categorized as CAM therapies, have been assimilated into conventional mainstream medicine. Progressive relaxation techniques, biofeedback, meditation, and cognitive-behavioral approaches have a well-documented theoretic basis with supporting scientific evidence. Other mind-body interventions still considered “alternative” by some include hypnosis, music, dance, art therapy, prayer, and mental healing. The integrative health practices category of biologically based therapies includes biologically based and natural-based practices, products, and interventions, some of which overlap with mainstream medicine’s use of dietary supplements. Herbal, orthomolecular, individual biologic therapies and special dietary treatments are encompassed in biologically based therapies. Herbs are plants or parts of plants that contain and produce chemical substances that act on the body. Some diet therapies are believed to promote health and prevent or control health. Proponents of diet therapies include religious factions such as Seventh-Day Adventist, or Jewish Kosher. Veganism, vegetarianism, raw food diets, and diets promoted by Drs. Atkins, Pritikin, and Weil are other examples of therapeutic nutrition. Orthomolecular therapies use differing concentrations of chemicals or megadoses of vitamins aimed at treating disease. Many biologic therapies are available but not currently accepted by mainstream medicine, such as the use of cartilage products from cattle, sheep, or sharks for treatment of cancer and arthritis or the use of bee pollen to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Methods that are based on the movement or manipulation of the body include chiropractic, osteopathy, and massage. Touch and manipulations with the hands have been used in healing and medical practice since the beginning of the history of medicine. At one time, the physician’s hands were considered the most important diagnostic and therapeutic tool. This remains true today, despite sophisticated diagnostic equipment and modalities (Box 30-2). Manual healing methods are based on the principle that dysfunction of a part of the body often affects secondarily the function of other discrete, possibly indirectly connected body parts. Theories have developed for correction of these secondary dysfunctions by realigning body parts or manipulating soft tissues. Chiropractic science is concerned primarily with the relationship between structure (spine primarily) and function (nervous system primarily) of the human body to preserve and restore health. Osteopathic medicine incorporates an extensive body of work that supports the use of osteopathic techniques for both musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal problems. Massage therapy is one of the oldest methods known in the practice of healthcare. One experimental pilot showed that using massage with music therapy during the perioperative period reduced postoperative prolactin levels and anxiety (Selimen and Andsoy, 2011). Many different massage techniques are aimed at helping the body heal itself through the use of manipulation of the soft body tissues. Energy therapies have been categorized into two groups: biofield therapies (those that focus on fields believed to originate within the body) and electromagnetic fields (those that originate from other sources). The existence of energy fields that originate within and around the body has not yet been definitively proven. However, many studies have examined the experiences of recipient or practitioner and the outcomes of this type of energy therapy. Examples of therapies with a biofield basis include acupuncture, reiki, qi gong, therapeutic touch (TT), and healing touch. Therapies that involve electromagnetic fields use unconventional pulsed fields, magnetic fields, alternating current fields, or direct current fields. These therapies have been clinically applied with patients who have arthritis, cancer, and pain (Kolthan, 2009). Patients have choices in how to manage their healthcare. However, surgery is the most invasive of all options. As healthcare consumers become more knowledgeable about their health they often seek complementary modalities to augment traditional Western medical therapies. Using the term alternative is actually misleading, which is why the field formerly known as CAM is more appropriately termed integrative health practices. Many progressive medical facilities embrace a holistic patient focus, exploring and integrating nontraditional healing modalities to support an individualized surgical experience. Biofield therapies represent a nonpharmacologic anxiolytic for surgical patients that may be integrated with an allopathic treatment plan. Many ancient cultures refer to a human biofield or “life force.” Sometimes referred to as “energy work,” biofield therapeutics are a range of interventions sharing common beliefs. First is the existence of a “universal force” or “healing energy” arising from God (as the person understands this being), the cosmos, the earth, or another supernatural source. Second, the human biofield, as part of the “universal field,” is dynamic, open, complex, and pandimensional. Human biofields are constantly changing and interacting with each other, the environment, and the universal force field. Third, the ability to use one’s biofield for healing is considered to be universal, although few people are aware of it without specific training. Last, practitioners intend to positively affect the patient’s biofield, either by direct contact or by using the hands in proximity, similar to the ancient practice of laying on of hands (Jackson and Keegan, 2008) (Table 30-1). TABLE 30-1 Comparisons of Selected Biofield Therapies Modified from Engebretson J, Wardell D: Energy-based modalities, Nurs Clin North Am 42:243–259, 2007; National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Energy medicine: an overview, available at http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam. Accessed October 7, 2012. Therapeutic touch (TT) is the contemporary interpretation of several ancient healing modalities. Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz developed TT in the early 1970s. The practice, like others that form part of the body of CAM, consists of learned skills for the conscious manipulation of human energies. In practice it is not necessary for the practitioner (healer) to actually touch the recipient (healee), because the energy field can be “felt” several inches away from the physical body. TT helps to aid in relaxation, reduces pain, promotes deeper and easier breathing, improves circulation of blood and movement of lymph fluids, reduces blood pressure, and strengthens the immune system. To work within biofields, the practitioner uses a model or map to focus the healing energy. Chakras, or energy centers, described by the Upanishads in the Vedas, the oldest literature of the East Indian people, are often used as a reference point. Although the most detailed descriptions are in the Upanishads, the attributes are found in the teachings of other cultures as widely geographic as the Sufis of the Middle East to the First Nations, particularly from the North American Southwest (Figure 30-3). TT practice lends itself well to the fast-paced surgical environment. The skills learned through study of TT provide a trained practitioner with the ability to center quickly and use intention to calm both himself or herself and others nearby in stressful situations. Research design, methods, techniques, and sample sizes are considerations for future studies into how biofield therapeutics may benefit surgical patients. Replicating past studies, as well as new research based on physiologic data and quantitative studies, is necessary (Research Highlight). It has become evident that the concepts involved in energy therapies need consistent definitions. If the concepts do not have preestablished definitions, they cannot be quantified or measured in meaningful ways. However, interest is high and research continues in an effort to better understand a phenomenon that seems to provide meaningful relief to the patient. Use of medical hypnotherapy in hospitals and clinics for perioperative care is not uncommon. Patients are seeking an active role in their treatment and are better informed regarding surgical options. Participating in perioperative medical hypnotherapy allows patients to take shared responsibility for their healing process, giving them a measure of control, because all hypnosis is self-hypnosis. Meaningful and active participation empowers a patient to enter into anesthesia and surgery with confidence. Surgery is a life-changing event, and each perioperative medical hypnotherapy patient is unique. The initial assessment serves to determine goals and explore questions relative to emotional as well as physical concerns. The hypnotherapist, working within the patient’s belief system, helps acknowledge areas of the patient’s concern as a multidisciplinary partnership of healing is forged in a patient-centered manner. As the hypnotherapist guides the patient into relaxation and induces hypnosis, both therapist and patient journey into the body, together addressing predetermined issues. Fear of the unknown, preprocedure anxiety, changes in body image, anticipated pain or nausea, loss of organs, and transplantation of new organs are some examples of issues that may be addressed in the perioperative setting (Gurgevich, 2012). Hypnosis compassionately allows a patient to explore emotions without judgment or expectation of those feelings. The practice of emotional awareness, of being present with feelings, and of holding those feelings sacred can bring a sense of peace and healing insights during a time of profound stress, such as that experienced by many surgical patients. Predetermined suggestions or affirmations may increase confidence in the healthcare team, increase compliance with the treatment plan, decrease blood loss, maintain intraoperative homeostasis, reduce the need for sedation or pain medication, decrease postoperative nausea or vomiting, and increase patient satisfaction. In a study done on patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery, it was found that preoperative relaxation techniques helped with postoperative pain and increased healing time (Topcu and Findik, 2012). Postoperative hypnotherapy sessions reinforce continued participation of patients in their healing process. This may take the form of establishing metabolic gauges in the “control room” or show a symbolic shield of protection, holding or sending color, light, or a certain feeling of safety to a specific part of the body. It may be expressing gratitude to and confidence in the medical and nursing community. Follow-up sessions allow both patient and hypnotherapist to evaluate attainment of preoperative goals, consider postoperative outcomes, and explore issues relevant to the ongoing healing process. Another therapy closely related to hypnosis is guided imagery. Imagery, or thinking in pictures, is the natural language of the unconscious mind and is used by the autonomic nervous system as a primary mode of communication. The autonomic nervous system controls unconscious body functions such as heart rate, immune function, digestion, blood flow, smooth muscle tension, and pain perception (Figure 30-4). Guided imagery for surgical patients may be in the form of pre-scripted tapes that lead the patient through relaxation exercises and provide healing suggestions. In other instances the perioperative nurse may assist the patient with guided imagery through the use of a calming, monotone voice; a smooth speaking delivery; and the use of relaxing images, such as a place in nature. The perioperative nurse coaches the patient to see, feel, smell, sense, and hear the imagined scene. Imagery may help patients build a “tool” to help in the postoperative period and lead to quicker recovery. According to Selimen and Andsoy (2011), benefits of guided imagery for surgery patients may include:

Integrative Health Practices

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Energy Therapies History and Background

Major Categories of Integrative Health Practices and Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Alternative Medical Systems

Mind-Body Interventions

Biologically Based Therapies

Manipulative and Body-Based Methods

Energy Therapies

Integrative Health Practices Use and Surgery

Energy Therapies

Therapy

Practice Initiated

Developers

Hand Placement

Theoretic Basis and Intent

Healing Touch

1981

American Holistic Nurses Association

Both on and off the body

Uses elements of healing science and therapeutic touch in conjunction with crystal and dowsing to treat whole person and specific disorders

Qi gong

Traditional

Chinese

At meridian points or short distance from the body

Qi follows meridians and body patterns to heal biologic disorders.

Reiki

Traditional

Buddhist

A few standardized hand placements on the physical body

Spiritual energy from universe is channeled by “masters” to heal the spiritual body, which in turn heals the physical body

1800s

Japan—Hawayo Takata

1936

United States—Mikao Usui

Therapeutic touch

1972

Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz

Primarily off the body 2-4 inches

Aligning Kunz’s Human Energy Field model with Martha Rogers’s Science of Unitary Human Beings, the centered practitioner assesses, directs, and modulates biofield energy to achieve relaxation response for healing of whole person

Reflexology

Traditional

Ancient method of treatment for ailments dating back to Egyptians and beyond

Application of pressure to sites on foot, hands, ears, and so on that correspond with organs and nerves to cause a reflex arc of stimulation to area in need

Promotes balance and wellness through nerve stimulation

Therapeutic Touch.

Perioperative Medical Hypnotherapy

Guided Imagery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree