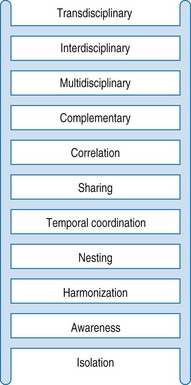

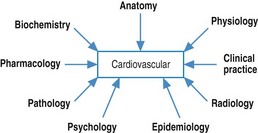

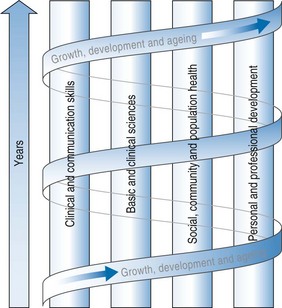

Chapter 22 In the later part of the 20th century medical education reformers advocated the combination of the disciplines and the organization of integrated learning experiences for students where they called upon knowledge and skills from across the disciplines in addressing patient cases, problems and issues. Integration was promoted in teaching and learning approaches rather than assuming that students would somehow integrate their disciplinary knowledge on their own. While integration was once regarded as a mark of innovation in medical education, it is now more widely accepted as a feature of all programmes. The degree of integration varies. Harden (2000) conceptualized a ‘ladder’ of integration with 11 steps or stages ranging from treating the disciplines in ‘isolation’ from each other to ‘interdisciplinary’ and ‘transdisciplinary’ designs (Fig. 22.1). A rationale for integrated learning can be found, however, in some of the writings in cognitive psychology. Regehr and Norman (1996) have summarized these writings. It is easier to retrieve and use information when it is combined in meaningful schemata. Regehr and Norman (1996) also refer to the concept of ‘context specificity’. The ability to retrieve an item from memory depends on the similarity between the condition or context in which it was originally learned and the context in which it is retrieved. Within these blocks students learn the basic sciences of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry together with social and behavioural sciences and clinical sciences as applied to normal and abnormal structures and functions within the systems (Fig. 22.2). More recently, some schools have adopted the concept of life cycle as a means of integrating content. The blocks or units which provide the basis for integration are organized according to stages in the life cycle. A common way of organizing a vertically integrated curriculum through the themes is to use a spiral approach. Within each of the themes there may be sub-themes or blocks which provide the basis for integration across the years of the medical course. For example, there may be a sub-theme such as growth, development and ageing which is present in each year of the course in one or more themes. The studies in each year revisit those from the previous year or years, build upon the sub-theme and extend the learning to higher levels and greater complexity. Each turn of the spiral represents an extension of the studies from the previous turn (Fig. 22.3). There are few medical courses which now rigidly maintain a preclinical/clinical divide, with the former presented in the earlier years of the course and the latter towards the end. Students now have early clinical learning experiences which increase in emphasis as they proceed through the course. There is a corresponding decrease in emphasis on the basic sciences, but they still have an important part to play in the clinical years in providing an explanation of the mechanisms of disease and disease processes. This increases the potential for integration of clinical and science disciplines. For example, anatomy and imaging are being presented in an integrated approach throughout medical courses. The establishment of clinical skills units, where students have opportunities to learn and practise skills in an intensive way, has also fostered integration, including the immediate application of concurrently learned anatomy and physiology. Dent et al (2001) have reported on an Ambulatory Care Teaching Centre (ACTC) in which students’ early experiences in the clinical skills centre integrate with patient-based experiences in the ACTC during subsequent system blocks.

Integrated learning

Introduction

The rationale for integrated learning

Approaches to integration

Vertical integration

Integrated learning