INTRODUCTION

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter you should:

Understand the genetics, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of hemophilias A and B.

Understand the genetics, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of von Willebrand disease.

No hematologic disorder has more historical import and portent than hemophilia. Figure 15-1 shows the descendants of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. One of their three sons, Leopold, Duke of Albany, suffered from a life-long bleeding -disorder, as did nine grandsons and great grandsons, including members of the Russian, Prussian, and Spanish royal families. Particularly foreboding was the affliction of young Prince Alexie, the only son of Czar Nicholas and Czarina Alexandra. His illness was but one of many travails that beset the Russian royal family and led to their dethronement and execution during the Bolshevik revolution.

Hemophilia

Hemophilia A (Factor VIII Deficiency)

Hemophilia B (Factor IX Deficiency)

Phenotypically Identical:

Hemarthroses

Hematoma

GI and GU Bleeding

HEMOPHILIA A (FACTOR VIII DEFICIENCY)

Hemophilia A is the inherited bleeding disorder most often associated with severe morbidity, frequently requiring hospitalization. It is due to deficiency of factor VIII. When activated, factor VIII forms a complex with activated factor IX, enabling the efficient proteolytic activation of factor X (see bottom of sidebar and Chapter 13 for more information about factor VIII). Hemophilia A occurs in about 1 in 5000 male births. The gene encoding factor VIII is located near the tip of the long arm of the X chromosome. Thus, hemophilia A is inherited in an X-linked manner, with female heterozygous carriers passing the disease on to half of their sons. The royal families depicted in Figure 15-1 comprise a typical kindred demonstrating X-linked transmission. About 30% of patients have no family history of abnormal bleeding. Most of these cases are due to spontaneous mutations. Although hemophilia A can occur in homozygous females, often owing to consanguinity, most females who bleed abnormally are heterozygous carriers of the hemophilia gene. Although the mechanism for their low factor VIII levels is not known, skewed X-inactivation (lyonization) has been hypothesized.

Patients with hemophilia A tend to have deep bleeding into joints (hemarthroses) or muscle beds, rather than bleeding from mucosal surfaces. Patients with repeated joint hemorrhage develop chronic disability due to swelling, deformity, severe pain, limitation of motion, and contractures that can be corrected only by joint replacement. Less often patients have bouts of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding and, rarely, intracerebral hemorrhage—a catastrophic event. Patients are assigned to one of three levels of severity according to plasma levels of factor VIII. These levels generally predict the phenotype of the patient. Those with 1% or less factor VIII (severe hemophilia) have an average of 20 to 30 episodes per year of either spontaneous bleeding or excessive bleeding after minor trauma. Patients with 1% to 4% factor VIII levels have moderate hemophilia, whereas individuals with greater than 4% factor VIII levels generally have bleeding episodes only after trauma or surgery.

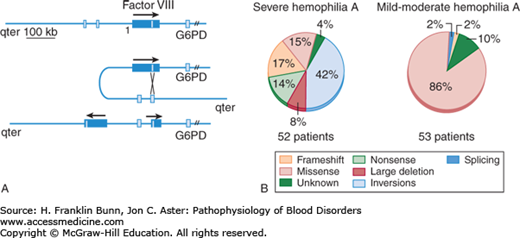

As might be surmised from the range of phenotypes, hemophilia A is a genetically heterogeneous disease. A wide variety of mutations of the factor VIII gene have been identified in hemophilia patients, including missense mutations, nonsense mutations leading to premature termination of translation, frame shifts, deletions, and rearrangements. The most commonly encountered mutation, depicted in Figure 15-2A, is an inversion that reverses the orientation of the 3′ end of the gene relative to the 5′ promoter and transcriptional start site. Alleles bearing this rearrangement, observed in about 50% of severe hemophilia A patients, make no factor VIII. As shown in Figure 15-2B, the great majority of mutations in patients with severe hemophilia A have either inversions, large deletions, nonsense mutations, or frame shifts, all of which preclude synthesis of full-length factor VIII. In contrast, those with moderate or mild hemophilia A usually have missense mutations in which full-length protein is produced but has impaired stability or function.

FIGURE 15-2

Mutations of factor VIII gene in hemophilia A. A) Inversion responsible for most cases of severe hemophilia A. B) Distribution of mutations in severe versus mild to moderate hemophilia A. (Modified with permission from Kaufman RJ and Antonarakis SE. Structure, biology and genetics of factor VIII. In Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Shattil SJ, et al, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice, 3rd Edition. New York, USA, Churchill Livingstone, 2001: 1858-1859.)

Because factor VIII is part of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, the partial thromboplastin time in a patient with hemophilia A is prolonged, whereas the prothrombin time is normal. Moreover, there are no abnormalities in the platelet count or in tests of platelet function such as the bleeding time. Assay of factor VIII coagulant activity is used not only in establishing the diagnosis but also in monitoring patients with hemophilia A and assessing their need for therapy. This test entails measurement of the clotting time after the patient’s plasma is mixed with factor VIII–deficient plasma. Molecular genetic testing is now available to diagnose hemophilia A during early fetal life for purposes of genetic counseling.