Chapter 4 Inherited and autoimmune subepidermal blistering diseases

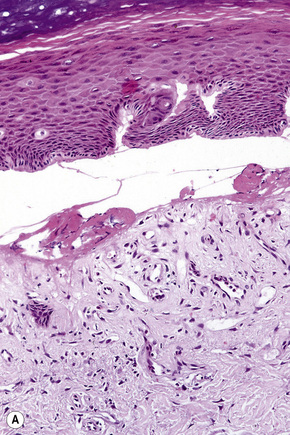

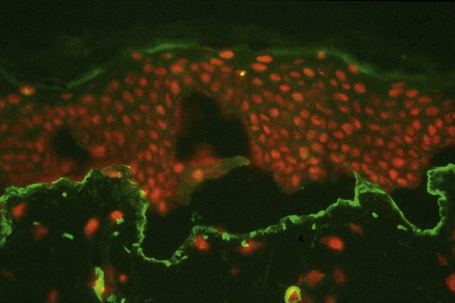

Blisters, which are clinically subdivided into vesicles (L. vesicula, dim. of vesica, bladder) and bullae (L. bubble), are defined as accumulations of fluid either within or below the epidermis and mucous membranes. Although somewhat arbitrary, the term ‘vesicle’ is applied to lesions less than 0.5 cm in diameter and ‘bulla’ to those greater than 0.5 cm. Subepidermal blisters, i.e., those that develop at the epidermal or mucosal basement membrane region, include inherited variants and acquired (often autoimmune mediated) conditions. The former are usually classified as noninflammatory (cell-poor) blisters whereas the latter are commonly inflammatory (cell-rich) in nature (Fig. 4.1).

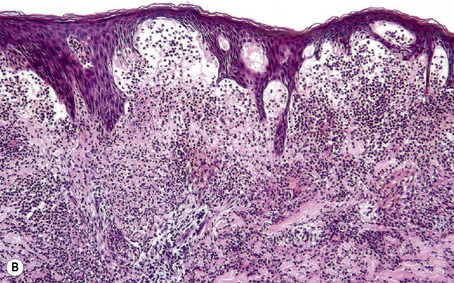

Subepidermal blisters may develop within the lower epidermis, the lamina lucida (e.g., bullous pemphigoid) or deep to the lamina densa (e.g., epidermolysis bullosa acquisita) (Fig. 4.2). In addition to clinical observations, the precise diagnosis of a blistering disorder requires careful histological and immunofluorescence correlation. When possible, the last should include indirect studies and, in particular, NaCl-split skin should be used as substrate as a mechanism of localizing the site of epidermodermal separation.1 If a sample has not been taken for indirect immunofluorescence, immunoperoxidase antigen mapping on paraffin-embedded material may on occasions be of value at least as a screening procedure. Although the results of electron microscopic investigations and, in particular, molecular studies have formed the basis of the current classification of subepidermal bullous dermatoses, such techniques are usually not essential to the everyday investigation of a patient with an acquired blistering disorder.

Split skin immunofluorescence

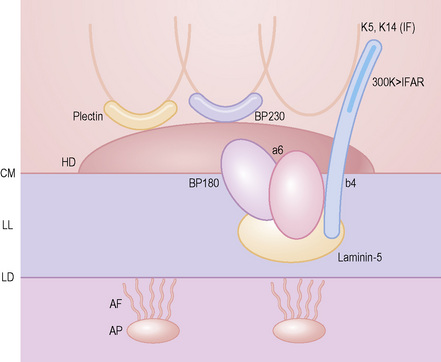

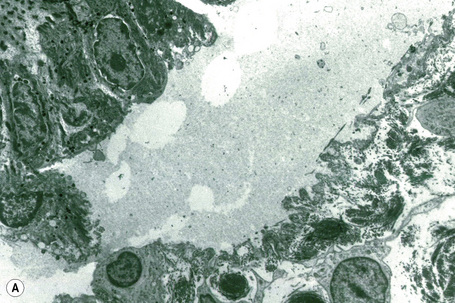

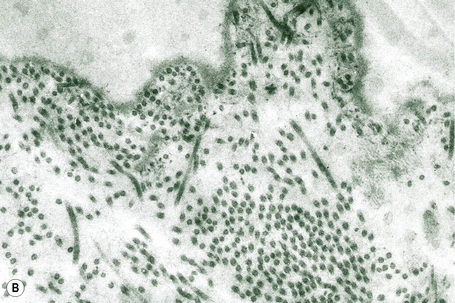

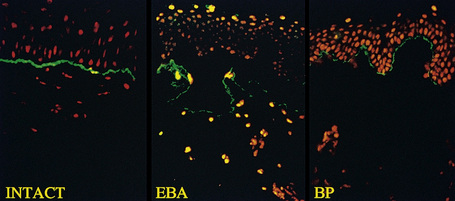

This technique represents a modification of indirect immunofluorescence (IMF) where normal skin is split through the lamina lucida of the basement membrane region to produce an artificial blister cavity (with the lamina densa lining the floor) for use as substrate. Artificial separation can be achieved by the suction technique (in vivo) or by immersion of normal skin in 1 M NaCl for 48 hours at 4°C (Fig. 4.3). In general, the latter technique is preferred.2 As such a split is invariably through the lamina lucida region (confirmed by electron microscopy or immunofluorescence) (Figs 4.4, 4.5), the technique enables precise localization of a circulating basement membrane zone antibody to either the floor or the roof of the artificial blister cavity. In bullous pemphigoid, pemphigoid gestationis, and the majority of cases of mucous membrane pemphigoid, linear immunofluorescence is found along the roof of the artificial blister whereas in diseases characterized by a sublamina densa split (e.g., epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, antilaminin mucous membrane pemphigoid, anti-p105 pemphigoid, anti-p200 pemphigoid, and bullous dermatosis of bullous lupus erythematosus), the immunofluorescent signal is found along the floor of the blister (see references 3 and 4 for a review) (Fig. 4.6). In some diseases, positive immunofluorescence may be found on either the roof or the floor or even at both sites simultaneously (e.g., linear IgA disease and some variants of mucous membrane pemphigoid). Such variable labeling reflects the antigen heterogeneity in a number of bullous dermatoses.

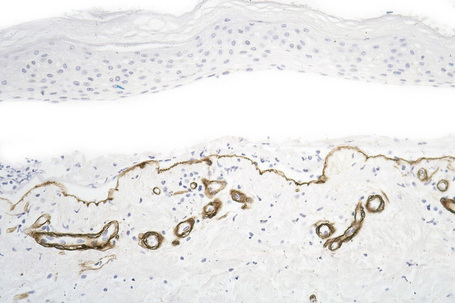

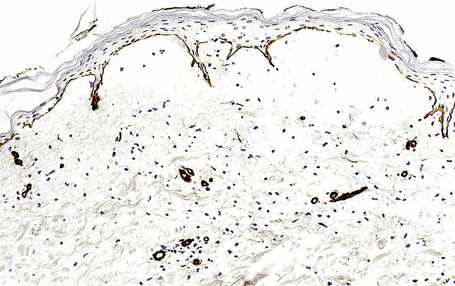

Immunoperoxidase antigen mapping

As an alternative to split skin immunofluorescence, paraffin-embedded sections of lesional skin have been proposed in a direct immunoperoxidase antigen mapping technique to identify the level of the epidermodermal separation.5–8This procedure localizes known basement membrane region constituents such as keratins 5/14, laminin, and type IV collagen to the roof or floor of the blister cavity. The site of blister formation can therefore be characterized as intrabasal, within the lamina lucida or deep to the lamina densa. For example, in epidermolysis bullosa simplex variants, all of these immunoreactants are present along the floor of the blister cavity. In bullous pemphigoid, keratin is present along the roof of the blister while laminin and type IV collagen are found along the floor (Fig. 4.7). In dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, all three immunoreactants are present in the roof of the blister (Fig. 4.8). However, in many hereditary and acquired blistering diseases the relevant antibodies against the target antigens do not work well in paraffin-embedded material and false-positive and false-negative results are common, making this method unreliable for use in routine diagnosis. For example, antigen mapping of the group of hereditary subepidermal blistering diseases is done exclusively on frozen sections with excellent results.

Epidermolysis bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) refers to a heterogeneous group of diseases in which the skin and sometimes the mucous membranes blister easily in response to mild trauma, hence the alternative title ‘mechanobullous dermatosis’, which has sometimes been applied.1 All are rare conditions; the estimated incidence for the group as a whole is in the order of 1:20 000. Apart from the acquired autoimmune variant (epidermolysis bullosa acquisita), they are all autosomal inherited disorders.

EB was initially described as a defined entity in 1886.2 This group of conditions has been classified in several ways over the years. The three major types were defined in a groundbreaking electron microscopy study in 1962.3 In 1988, the contemporary classification and subtyping of the major variants commenced with the first consensus meeting of the Steering Committee of the National EB Registry (established in 1986) held in conjunction with the American Academy of Dermatology.4,5 At that time, 23 seemingly clinically distinct variants were recognized (Table 4.1).5 In the following decade, a second consensus conference was held.6 As a result of the considerably increased number of cases available for study, a much greater degree of clinical overlap between the various subtypes was recognized. For this reason and because of a much better understanding of the molecular basis for many of the variants of EB, a considerably simplified classification system was recommended at that time (Table 4.2).7,8 Most recently, at the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB, the classification scheme was further revised and this current proposed scheme forms the framework for the discussion in this chapter (Tables 4.3, 4.4).9 Research over the past two decades has generated a wealth of literature specifically addressing the molecular basis of the various subtypes of EB. As a result, it is now possible to subgroup EB on the basis of the level of separation within the basement membrane region as well as on specific molecular findings. Though molecular classification now drives our understanding of this disease group, knowledge of the traditional clinical subtypes can be helpful in explaining the disease course to patients, despite the often overlapping spectrum of manifestations.

Table 4.1 First consensus conference (1988): classification of subepidermal blisters

| EB simplex |

| Localized |

| EB simplex of hands and feet (Weber-Cockayne variant) EB simplex with anodontia/hypodontia (Kallin syndrome) |

| Generalized |

| EB simplex, Koebner variant EB simplex herpetiformis (Dowling-Meara variant) EB simplex with mottled or reticulate hyperpigmentation with or without punctate keratoderma EB simplex superficialis EB simplex, Ogna variant Autosomal recessive EB simplex (letalis) with or without neuromuscular disease EB simplex, Mendes da Costa variant Reproduced with permission from Fine, J.D. et al (1991) Pediatrician, 18, 175–187. DDEB, dominant dystrophic EB; DEB, dystrophic EB; RDEB, recessive dystrophic EB. |

| Junctional EB |

| Localized |

| Junctional EB, inversa Junctional EB, acral/minimus Junctional EB, progressiva variant |

| Generalized |

| Junctional EB, gravis variant (Herlitz variant) Junctional EB, mitis variant (non-Herlitz variant; EB atrophicans generalisata mitis; generalized atrophic benign EB) Cicatricial junctional EB |

| Dystrophic EB |

| Localized |

| RDEB, inversa DDEB, minimus DDEB, pretibial RDEB, centripetalis |

| Generalized |

| Autosomal dominant forms of DEB DDEB, Pasini variant DDEB, Cockayne-Touraine variant transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn Autosomal recessive forms of DEB RDEB, gravis (Hallopeau-Siemens variant) RDEB, mitis |

Table 4.2 Second consensus conference (1999): classification of epidermolysis bullosa

| Major EB type | Major EB subtype | Protein/gene systems involved |

|---|---|---|

| EBS (‘epidermolytic EB’) | EBS-WC | K5, K14 |

| EBS-K | K5, K14 | |

| EBS-DM | K5, K14 | |

| EBS-MD | Plectin | |

| Junctional EB | JEB-H | Laminin-5* |

| HEB-nH | Laminin-5; type XVII collagen | |

| JEB-PA† | α6β4 integrin‡ | |

| DEB (‘dermolytic EB’) | DDEB | Type VII collagen |

| RDEB-HS | Type VII collagen | |

| RDEB-nHS | Type VII collagen |

DDEB, dominant dystrophic EB; EBS-DM, EBS Dowling-Meara; EBS-K, EBS, Koebner; EBS-MD, EBS with muscular dystrophy; EBS-WC, EBS, Weber-Cockayne; JEB-H, junctional EB, Herlitz; JEB-nH, junctional EB, non-Herlitz; JEB-PA, junctional EB with pyloric atresia; RDEB-HS, recessive dystrophic EB, Hallopeau-Siemens; RDEB-nHS, recessive dystrophic EB, non-Hallopeau-Siemens.

* Laminim-5 is a macromolecule composed of three distinct (α3, β3, γ2) laminin chains; mutations in any of the encoding genes result in a junctional EB phenotype.

† Some cases of EB associated with pyloric atresia may have intraepidermal cleavage or both intralamina lucida and intraepidermal clefts.

‡ α6β4 integrin is a heterodimeric protein; mutations in either gene have been associated with the JEB-PA syndrome.

Reproduced from Fine et al (2000) J Am Acad Dermatol, 42, 1051–1066 from American Academy of Dermatology.

Table 4.3 Third consensus conference (2007): classification of epidermolysis bullosa

| Major EB type | Major EB subtype | Protein involved |

|---|---|---|

| EBS | Suprabasal Lethal acantholytic EB Plakophilin deficiency EBS superficialis (EBSS) | Desmoplakin Plakophilin-1 ? |

| Basal EBS, localized (EBS-loc)+ EBS, Dowling-Meara (EBS-DM) EBS, other generalized (EBS, gen-nonDM; EBS, gen-nDM)^ EBS with mottled pigmentation (EBS-MP) EBS with muscular dystrophy (EBS-MD) EBS with pyloric atresia (EBS-PA) EBS, autosomal recessive (EBS-AR) EBS, Ogna (EBS-Og) EBS, migratory circinate (EBS-migr) | K5, K14 K5, K14 K5, K14 K5 Plectin Plectin, α6β4 integrin‡ K14 Plectin K5 | |

| Junctional EB | JEB, Herlitz (JEB-H) JEB, other (JEB-O) JEB, non-Herlitz, generalized (JEB-nH gen)$ JEB, non-Herlitz, localized (JEB-nH loc) JEB with pyloric atresia (JEB-PA) †JEB, inversa (JEB-I) JEB, late onset (JEB-lo)# LOC syndrome (laryngo-onycho-cutaneous syndrome) | Laminin-332 (laminin-5)* Laminin-332; type XVII collagen (BP180) Type XVII collagen α6β4 integrin‡ Laminin-332 ? Laminin-332 α3 chain |

| DEB (‘dermolytic EB’) | Dominant dystrophic EB (DDEB) DDEB, generalized (DDEB-gen) DDEB, acral (DDEB-ac) DDEB, pretibial (DDEB-Pt) DDEB, pruriginosa (DDEB-Pr) DDEB, bullous dermolysis of the newborn (DDEB-BDN) Recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) RDEB, severe generalized (RDEB-sev gen)@ RDEB, generalized other (RDEB-O) RDEB, inversa (RDEB-I) RDEB, pretibial (RDEB-Pt) RDEB, pruriginosa (RDEB-Pr) RDEB, centripetalis (RDEB-Ce) RDEB, bullous dermolysis of the newborn (RDEB-BDN) | Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen Type VII collagen |

| Kindler syndrome | Kindlin-1 |

Rare variants are italicized.

Dominant dystrophic EB; EBS-DM, EBS Dowling-Meara; EBS-K, EBS, Koebner; EBS-MD, EBS with muscular dystrophy; EBS-WC, EBS, Weber–Cockayne; JEB-H, junctional EB, Herlitz; JEB-nH, junctional EB, non-Herlitz; JEB-PA, junctional EB with pyloric atresia; RDEB-HS, recessive dystrophic EB, Hallopeau-Siemens; RDEB-nHS, recessive dystrophic EB, non-Hallopeau-Siemens.

+ Previously termed EBS, Weber-Cockayne

^ Includes cases previously termed EBS-Koebner

‡ α6β4 integrin is a heterodimeric protein; mutations in either gene have been associated with both EBS-PA and JEBS-PA. Some cases of EB associated with pyloric atresia may have intraepidermal cleavage or both intralamina lucida and intraepidermal clefts.

* Laminin-332 (laminin-5 is a macromolecule composed of three distinct (α3, β3, γ2) laminin chains; mutations in any of the encoding genes result in a junctional EB phenotype.

$ Previously termed generalized atrophic benign EB (GABEB).

# Previously termed EB progressiva.

@ Previously termed RDEB, Hallopeau-Siemens.

† Some cases of EB associated with pyloric atresia may have intraepidermal cleavage or both intralamina lucida and intraepidermal clefts.

‡ α6β4 integrin is a heterodimeric protein; mutations in either gene have been associated with the JEB-PA syndrome.

Adapted from Fine et al (2008) J Am Acad Dermatol, 58, 931–50 from American Academy of Dermatology.

Table 4.4 Simplified classification of epidermolysis bullosa

| Subtype | Mutation | |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex | Suprabasal Basal | Plakophilin-1; desmoplakin Keratin 5 or 14; plectin; α6β4 integrin |

| Junctional | Herlitz Non-Herlitz | Laminin-332 (laminin-5) Laminin-332; type XVII collagen; α6β4 integrin |

| Dystrophic | Dominant Recessive | Type VII collagen Type VII collagen |

| Kindler syndrome | Kindlin-1 |

In 1999, a fourth category – hemidesmosomal EB (where the level of split is within the hemidesmosome) – was added.10 This provisional category has now been removed and Kindler syndrome now constitutes a fourth major category. The most recent classification, which takes into account the current precise molecular data which is now known for virtually all of the subtypes of this disease, is particularly valuable when considering the pathological basis of EB and forms the basis for this account. There have been some changes in nomenclature based on an attempt to produce names that are more accurately descriptive of the diseases and concordant with current molecular classification of this disease.

Mutations of sundry types in a variety of genes encoding plakophilin-1 (PKP1), desmoplakin (DSP), keratins 5 and 14 (KRT5, KRT14), plectin (PLEC1), BP180, α6 and β4 integrin subunits (ITGA6, ITGB4), laminin-5 (now termed laminin-332 and encoded by LAMA3, LAMB3, LAMC2), types XVII and VII collagen (COL17A1, COL7A1) and kindling-1 (KIND1) currently account for the different subtypes of EB (a more detailed account of these basement membrane proteins is given in Chapter 1).10–12

Clinical evaluation of a patient with suspected EB should include the age of onset and nature and distribution of the cutaneous lesions and whether or not scarring and contractures are present. In addition, the family pedigree should be studied and the patient investigated for the presence or absence of extracutaneous involvement (eyes, oropharynx, larynx, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts, and musculoskeletal system) and other specific lesions (including enamel hypoplasia, anodontia or hypodontia, pyloric atresia, and muscular dystrophy) that might point towards a particular variant.4,5

Four major subtypes of EB are now recognized: simplex, junctional, dystrophic and Kindler Syndrome: 4–7,9

Clinical features

EB simplex (EBS)

Two major types of EB simplex (with 12 subtypes) are now recognized:

Suprabasal EBS

Three suprabasal subtypes are recognized; all of them are rare variants.

Lethal acantholytic EB

Lethal acantholytic EB has been described in two cases with severely defective skin and mucosal epithelia.19 The disease was lethal in the neonatal period due to epidermolysis that was first noted during parturition leading to uncontrollable loss of fluid from the skin. Additional defects included universal alopecia and complete shedding of nails and the presence of neonatal teeth. Histology revealed clefting of the suprabasal layer producing a tombstone-type appearance reminiscent of pemphigus vulgaris. Molecular investigation revealed that the patient had inherited two different nonfunctional copies of the gene encoding desmoplakin (DSP, a desmosomal protein that links the transmembrane cadherins to the various proteins of the cytoplasmic intermediate filaments), one from each parent, indicating that the disease is autosomal recessive. The mutations both lead to truncation of the desmoplakin protein and an inability to act as a linker. Additional cases will be necessary to further define this syndrome.

Plakophilin deficiency (ectodermal dysplasia-skin fragility syndrome, McGrath syndrome)

Plakophilin is a required component of desmosomes and an important protein in ectodermal development. The rare deficiencies in this protein result in a recently described inherited disease known as ectodermal dysplasia-skin fragility syndrome. Plakophilin-1 (PKP1) deficiency is an autosomal recessive disease that is associated with skin fragility and an inflammatory response resulting in erosions, scale-crust, and progressive palmoplantar keratoderma. Ectodermal effects such as sparse hair and anhidrosis and astigmatism are also noted.20 While initially described in a single child, approximately ten cases with mutations in this gene have now been described.20,21

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex superficialis

This rare form of EB transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion was first described in 1989. It specifically differs from the other simplex variants by the site of epidermal cleavage: variable subcorneal split between the stratum corneum and granular cell layer or sometimes within the stratum spinosum rather than intrabasal.22 Patients present at birth or within the first 2 years of life with erosions and crusts sparing the palms and soles. Atrophic scarring, nail dystrophy, and milia are additional common features; oral and ocular epithelia can be affected.23 As well as the cutaneous manifestations, anemia and gastrointestinal lesions affect a minority of patients. Some cases are associated with mutations causing structural dysfunction of type VII collagen.23 The condition may be clinically confused with peeling skin syndrome but in the latter there are no blisters and peeling is continous and spontaneous.

Basal EBS

Nine subtypes of basal EBS are currently recognized, five of which are very rare.

EB simplex, localized (Weber-Cockayne; EB simplex of the hands and feet)

This is the most common form of epidermolysis bullosa and has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.4 5 Lesions are limited to the palms and soles and are usually detected in infancy or the first few years of life (Fig. 4.9). Occasionally, in patients with mild involvement, blisters and erosions may not develop until childhood or even early adulthood in association with strenuous activity. The lesions, which sometimes heal with atrophic scarring, show seasonal variation, often occurring only in the summer months. Hyperhidrosis may sometimes be present. Milia, atrophic scarring, and nail dystrophy are uncommon features.5,7 The teeth are uninvolved and there is no evidence of any systemic involvement, except perhaps for oral erosions, which may affect an appreciable number of patients in infancy.7 Ocular lesions are not a feature. Repeated episodes of secondary infection may occur in some patients. Postinflammatory hyper- and hypopigmentation may sometimes be a cosmetic problem.8

EBS, Dowling-Meara (EBS herpetiformis)

This variant, which is the second commonest form of EB simplex, shows clinical features resembling dermatitis herpetiformis and has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance (Fig. 4.10).7,24–27 Herpetiform grouping of blisters is characteristic. Lesions are usually present at birth and have a distribution sometimes mimicking severe dystrophic or junctional disease.7 Some patients die in early infancy due to infection, fluid loss or electrolyte imbalance.1 Milia formation is common, but atrophy and scarring are rare.7 Distal flexural contractures are occasionally present.25 Nail dystrophy is often found and palmoplantar keratoderma is characteristic. Anodontia and hypodontia have also been described. Normalization during episodes of high fever is a typical finding but seasonal variation is not a feature.26 Blistering significantly improves with advancing years.27 Mutations in keratins 5 and 14 underlie this disease.28–31 Death as a result of complications of the disease is rare and generally occurs by age 1 as a result of sepsis or respiratory failure.32

EBS, other generalized (includes Koebner variant)

This group has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance and includes primarily those cases previously termed Koebner-type and all other generalized subtypes of EBS.5 In the Koebner variant, blisters are present at birth or shortly thereafter and, although the entire body may be affected, lesions are particularly severe on the extremities, where the dorsal surfaces tend to be involved (Fig. 4.11).5 The blisters usually heal without scarring or atrophy and milia are very uncommon.5 The eruption often worsens in the summer months. The nails are rarely dystrophic and teeth abnormalities are typically absent. Although oral lesions may be present in infancy, systemic involvement is not a feature of this variant.

EBS with mottled pigmentation

This autosomal dominant variant was originally described in six members of a single kindred.33 The cutaneous lesions are similar to the Dowling-Meara variant with the addition of mottled or reticulate pigmentation, particularly affecting the neck and trunk. Atrophic scarring, milia, and nail dystrophy are uncommon. Punctate keratoderma affecting the palms and warty hyperkeratotic lesions involving the hands, elbows, and knees may be additional features.33–35 Dental caries is also sometimes present and intraoral lesions are occasionally seen.

EBS with muscular dystrophy (pseudojunctional EB)

This is an autosomal recessive variant in which patients concomitantly develop muscular dystrophy or exceptionally myasthenia gravis and even cardiac involvement.36–38 Blisters and erosions present at birth or soon thereafter and are usually generalized. Patients may also suffer from atrophic scarring, milia, nail dystrophy or anonychia, alopecia, and oral lesions36,37 Severe mucose membrane involvement is rare.39 The mortality of this variant is high.6 Mutations in plectin are associated with these forms of the disease.40–42 Plectin is a large (greater than 500 kD) intermediate filament binding protein that provides mechanical rigidity to cells by acting as crosslinking adaptor to the cytoskeleton.43 The PLEC1 gene bears a domain structure similar to BPAG1, indicating they belong to a common family and may have similar functions.

A lethal variant of EBS with mutations in plectin at the level of the plakin domain may occur exceptionally and it is associated with aplasia cutis of the limbs and developmental impairment.42

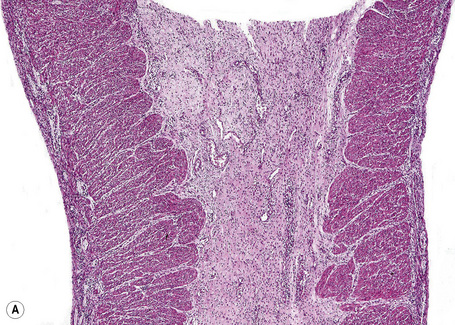

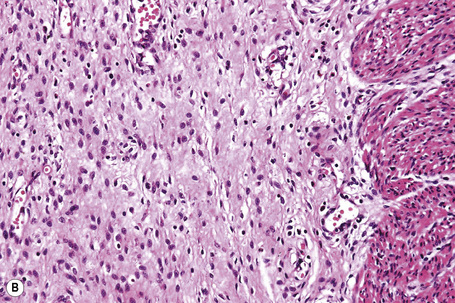

EBS with pyloric atresia

This category was placed in the provisional hemidesmosomal category in the prior edition of this book. Cases with pyloric atresia are currently considered in two groups: EBS discussed here, and another category in junctional EB discussed below. This is a rare variant of epidermolysis bullosa in which affected infants are at risk of ureterovesical junction obstruction with fibrosis involving the entire urinary tract and aplasia cutis congenita in addition to pyloric atresia (Figs 4.12, 4.13).44–47 Polyhydramnios is also seen. The pyloric atresia may be due to a diaphragm or stenosis (Fig. 4.14). The mortality rate of this variant is very high, up to 78% of affected infants succumbing.46 It appears to be the most lethal form in the EBS category. Mutations in both plectin and α6β4 integrin subunits (junctional EB) have been described.48 Since both α6β4 integrin and plectin are expressed in villous trophoblast from the first trimester of pregnancy this feature has been used successfully for the prenatal diagnosis of this group of conditions.49

Fig. 4.12 EB with pyloric atresia: stillborn infant with widespread blistering.

By courtesy of M.J. Tidman, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 4.13 EB with pyloric atresia: in addition to blistering there is also deep ulceration.

By courtesy of M.J. Tidman, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

EBS, autosomal recessive

Autosomal recessive EBS is generalized with onset at birth. Blistering is prominent with mild atrophic scarring. Ichthyotic plaques and focal palmoplantar keratoderma are sometimes encountered. Nails may be dystrophic or absent. Anemia, growth retardation, dental caries, and constipation can be complications.9 Mutations in keratin 14 underlie this disease; keratin 5 mutations have not been described.50,51

EBS, Ogna

This form is autosomal dominant and presents at birth. It primarily involves acral sites, but can become widespread. Blistering is prominent and onychogryphosis is common. A tendency to bruise has been described.9,52 Lack of muscular involvement distinguishes this form of disease from EBS with muscular dystrophy described above; the mutation genotype may be predictive of disease expression.42,53

EBS, migratory circinate

This generalized form of EBS presents at birth with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Blistering is very prominent and associated with a migratory circinate erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.9 Mutations in keratin 5 have been described, but none is currently reported in keratin 14.39,54,55

Hemidesmosomal EB

This group previously included three variants:

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa

Two major subtypes of this variant are recognized: junctional EB-Herlitz and junctional EB-non-Herlitz (Other). This later group encompasses both localized and generalized forms, cases with pyloric atresia, and three additional very rare variants under the newly revised classification scheme.9 Junctional EB with pyloric atresia was classified in the hemidesmosomal group in the prior classification scheme. All have an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance.

Junctional EB, Herlitz (Herlitz, gravis variant of junctional EB, EB hereditaria letalis, EB atrophicans generalisata gravis)

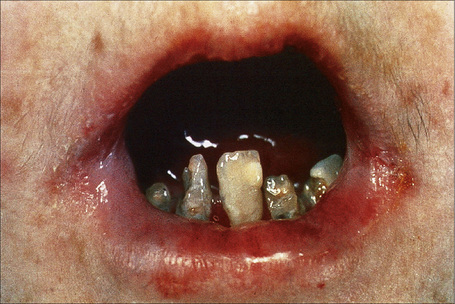

Within this generalized variant, no additional subtypes are recognized. Blisters and erosions are present at birth accompanied by scarring and atrophy (Fig. 4.15).56–58 Milia may be a feature.7 Healing with the formation of exuberant, vegetative or tumorous granulation tissue is a pathognomonic feature (Fig. 4.16).5 This is found particularly around the mouth, sides of the neck, trunk, and about the nails.4 The nails may be dystrophic or absent and scarring alopecia is sometimes evident.5 Severe oral involvement (including scarring and microstomia) is usually present and pitted dystrophic enamel is characteristic (Fig. 4.17). Dental caries are frequently severe. Other features may include musculoskeletal deformities, gastrointestinal lesions, laryngotracheal stenosis, and genitourinary and ocular involvement. Esophageal involvement may result in stenosis. Perforation with resultant infection is an important cause of death. Severe growth retardation and anemia are usually evident. Infantile mortality is high (42.2%).7 Mutations in one of the three subunits of laminin-332 underlie this syndrome.59–61

Fig. 4.15 Junctional EB (Herlitz): newly born infant with blistering and nail involvement.

By courtesy of J. McGrath, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 4.16 Junctional EB (Herlitz): infant showing granulation tissue at the edge of a healing blister.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Junctional EB, Other

The category contains six subtypes, two common and four rare.

JEB, non-Herlitz, generalized (generalized non-Herlitz junctional EB, EB atrophicans generalisata mitis, generalized atrophic benign EB (GABEB), hemidesmosomal EB, junctional EB mitis)

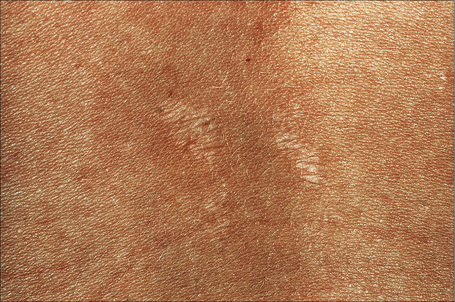

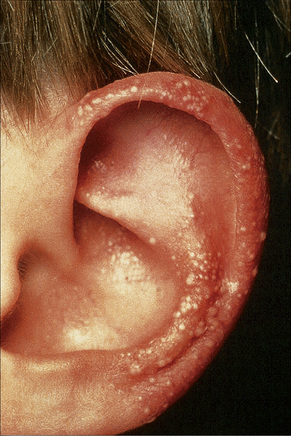

This somewhat milder form, in which the cutaneous features are similar to the gravis form, includes some patients with laminin-332 gene mutations and others with mutations in type XVII collagen previously classified in the hemidesmosomal group.9,62 Systemic involvement is typically mild or absent.63–66 Patients present at birth with extensive blistering and erosions accompanied by mild scarring and widespread cigarette paper-like atrophy. Variable hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation are characteristic.63 Skin lesions may be exacerbated during summer. Milia are variably present. Exuberant granulation tissue is less common than in the Herlitz variant. Other features include dystrophic or absent nails (Fig. 4.18), oral erosions with mild scarring, pitted dystrophic enamel, and severe dental caries. Ocular lesions include recurrent corneal erosion, blistering, and corneal scarring.64 Follicular atrophy with resultant alopecia involving the scalp, axillary, and pubic hair in addition to sparse eyelashes and eyebrows is common (Fig. 4.19).63 Large or multiple melanocytic nevi have also been described as part of the phenotype58 but this is not currently believed to be a specific feature.5 Contractures do not develop. Systemic involvement is usually limited to mild laryngeal and/or esophageal lesions.4 Growth may be retarded and anemia is present in some patients. Infantile mortality is high (up to 44.7%).7,32

Fig. 4.18 Generalized atrophic benign EB: there is scarring and complete absence of nails.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

JEB, non-Herlitz, localized

This milder and localized form of JEB is associated with mutations in type XVII collagen rather than laminin-332.67,68 Genotypic correlations and immunofluorescence antigen mapping may allow distinction of this form from the more several generalized form.68

JEB with pyloric atresia

All EB with pyloric atresia was previously placed in the now defunct hemidesmosomal category. These cases are now divided into two categories within EBS and JEB. While both plectin and α6β4 integrin subunit mutations have been noted in EBS with pyloric atresia, only the latter is believed associated with JEB with pyloric stenosis.69–71 The clinical features are similar, with generalized blisters present from birth associated with atrophic scarring, dystrophic or absent nails, and milia on occasion. Large areas of aplasia cutis have been described.67 This disease is usually fatal at an early age.

JEB inversa

Lesions, which are present at birth or develop in early infancy, are initially generalized, but later are predominantly localized to inverse (flexural) sites including the axillae and groin.5 Blisters and erosions are accompanied by atrophic scarring and nails may be dystrophic or absent. Other features that are sometimes evident include mouth erosions, maldeveloped teeth with enamel hypoplasia, and occasional gastrointestinal lesions, particularly affecting the esophagus and anus. Mutations in the subunits of laminin-332 are noted.9,58

JEB-late onset (progressiva)

In this variant, lesions do not present until late childhood, and consist of blisters and erosions affecting the hands, elbows, knees, and feet.5 Nails may be dystrophic or absent and enamel hypoplasia is characteristic. Mouth erosions may be evident. Mild finger contractures are sometimes a complication.3,5 The mutation underlying this form of the disease is unclear.9

Laryngo-onycho-cutaneous (LOC) syndrome

A mutation in the gene encoding the laminin-332 α3 chain resulting in an unusual N-terminal deletion underlies this syndrome.72 It was first described by Shabbir and colleagues in 22 patients of Punjabi extraction and about 10 additional cases have been described.73,74 So far, this autosomal recessive condition has not been described outside of this population. It can occur in a nonconsanguineous context. It consists of epithelial defects resulting in cutaneous erosions, nail dystrophy, and chronic conjunctival and laryngeal granulation tissue. Symblepharon and blindness are serious complications. Airway obstruction and infection can also be problematic. The degree of skin fragility is less than that seen in other variants of JEB. Under the new classification system, based on molecular and clinical similarities to JEB, this syndrome has been added as a rare variant.9,59

Dystrophic EB

Two major subtypes – dominant dystrophic EB and recessive dystrophic EB (Hallopeau-Siemens) – are recognized and these are categorized into three major subtypes (one dominant and two recessive) and nine rare dominant or recessive groups. All subtypes are associated with mutations in the gene encoding type VII collagen. 9

Dominant dystrophic EB

Five subtypes are recognized; four of these are rare.

Dominant dystrophic EB, generalized

Autosomal dominant EB, generalized includes both the Cockayne-Touraine and Pasini variants. This is because the two conditions are characterized by identical type VII gene mutations and the albopapuloid lesions (white perifollicular papules and plaques) have been found to be an inconsistent finding (Fig. 4.20).6,7 Generalized blisters are seen at birth (Fig. 4.21a).4,8 Alopecia may be present and milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic or absent nails are typical features (Fig. 4.21b). Oral involvement may be mild or absent. Enamel hypoplasia is sometimes evident. Gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract involvement is seen in a minority of patients. There is a slightly increased risk of basal cell carcinoma and melanoma.75

Dominant dystrophic EB, acral

In this mild autosomal dominant localized variant, lesions present at birth or in early childhood, particularly in an acral distribution. Blisters and erosions in the absence of other significant lesions except for atrophic scarring, milia, and nail dystrophy may cease altogether after childhood.1 Extracutaneous manifestations have not been recorded.

Dominant dystrophic EB, pretibial

This is a mild, localized, and typically symmetrical autosomal dominant form. An autosomal recessive variant has recently been described (see below).76 The onset is often delayed, patients usually presenting in early childhood.77 Blisters and erosions accompanied by atrophic scarring and milia are particularly seen on the pretibial region and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figs 4.22, 4.23). The scarring may have a violaceous appearance reminiscent of hypertrophic lichen planus.76 Lesions are also sometimes seen on the forearms and trunk.76 Pruritus and nail dystrophy are common. There are no teeth or hair changes.77

Fig. 4.22 Dystrophic EB–pretibial: extensive erosions with scarring are localized to the front of both shins.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Dominant dystrophic EB, pruriginosa

This variant, which presents in childhood, includes dominant and recessive variants (see below).78 Patients present with highly pruritic, violaceous nodular prurigo-like nodules developing against a background of blisters, milia, nail dystrophy, and albopapuloid lesions.

Dominant dystrophic EB, bullous epidermolysis of the newborn

This exceptionally rare, self-limiting condition presents in the newborn with blisters that usually resolve within the first 2 years and heal with mild atrophy, milia, and scarring.79,80 Most cases have been inherited as an autosomal dominant, although recessive variants have also been documented.6

Recessive Dystrophic EB

This category is composed of seven subtypes, of which five are rare.

Recessive dystrophic EB, severe generalized (Hallopeau-Siemens; polydysplastic EB; EB gravis)

This autosomal recessive variant is a much more serious form than its autosomal dominant counterpart.4,8 Blisters and erosions are present at birth and, atrophy, scarring, anemia, and growth retardation are consistently present (Figs 4.24, 4.25). Nikolsky’s sign is positive. Destructive involvement of the distal peripheries results in contractures and severe deformities including the characteristic ‘mitten lesions’ (pseudosyndactyly) of the hands and feet (Figs 4.26–4.28).81 If the latter is left untreated, there may eventually be resorption of the underlying bones (autoamputation). Nail dystrophy and milia are marked, and scarring alopecia is common (Fig 4.29). Oral involvement is severe, with blisters, erosions, and scarring. Excessive caries are usual. Gastrointestinal and renal complications are common.82,83 There is often conjunctival involvement with keratitis and scarring, and lesions of the mucous membranes result in difficulty in opening the mouth, dysphagia, and esophageal stricture formation, with some infants eventually succumbing to terminal respiratory infections (Fig. 4.30).84 Anal and genitourinary involvement may also be present. Squamous cell carcinoma is a common complication of the cutaneous scarring (occurring in 39.6% of cases) and is a significant cause of mortality (Figs 4.31–4.33).85,86 Tumors are frequently multiple, have an aggressive behavior, and may be associated with extensive metastatic spread. Melanoma much less commonly develops. This variant of EB has a high mortality: 38.7%.7

Fig. 4.25 Recessive dystrophic EB (Hallopeau-Siemens): note the scarring and extensive erosions.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 4.28 Recessive dystrophic EB (Hallopeau-Siemens): there is gross deformity of the knees.

By courtesy of J. McGrath, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 4.29 Recessive dystrophic EB (Hallopeau-Siemens): note the conspicuous milia.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Recessive dystrophic EB, generalized other

This type is often referred to as non-Hallopeau-Siemens type. In contrast to the severe generalized form, anemia and mental retardation are less common and dental caries are not increased. In this variant the features are similar to the Hallopeau-Siemens variant except that the extracutaneous lesions and complications (e.g., anemia, mental retardation, and dental caries) are less severe and the risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is diminished (14.3%).4,8 The mortality for this variant of EB is 10.0%.87 Genotypic differences in mutational types and sites in the gene encoding type VII collagen likely underlie differences in the phenotypic expression of this disease.88

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree