Inguinal Hernia: Open Approaches

Michael D. Paul

Kamal M.F. Itani

DEFINITION

Inguinal hernia is one of the most commonly encountered clinical problems for the general surgeon.

An inguinal hernia is an opening in the myofascial plain of the oblique and transversalis muscles that can allow herniation of intraabdominal or extraperitoneal organs.

There are three potential spaces for an inguinal hernia: (1) an indirect hernia occurs lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels and through the opening that accommodates the cord structures in men and the round ligament in women, (2) a direct hernia occurs through Hesselbach’s triangle, and (3) a femoral hernia occurs through the femoral canal medial to the femoral vein.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patients present with complaints of either a bulge in the groin or groin pain.

The differential diagnosis for a groin bulge includes inguinal lymphadenopathy, hydrocele, varicocele, a testicular mass, a cord lipoma, or an iliac or femoral aneurysm.

The differential diagnosis for groin pain includes testicular pathology, ilioinguinal strain, or an athlete’s hernia.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The presence of an inguinal hernia can almost always be confirmed on physical examination. Both groins and testicles should be assessed for masses. A reducible mass is best felt with the patient standing and providing intermittent Valsalva such as a cough. A femoral hernia will be felt below the inguinal ligament, adjacent to the femoral vessels.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

If the diagnosis cannot be definitely made with physical examination, ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan can be used to assess the integrity of the abdominal wall.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The bulk of surgical treatment is discussed in the “Techniques” section. Here, consider indications and other more general concerns, such as the following:

Preoperative Planning

The role of routine antibiotic prophylaxis for elective inguinal hernia remains controversial. There is a body of literature indicating no statistically significant advantage to the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the performance of routine inguinal hernia repair with or without the use of mesh. Nevertheless, many surgeons argue that antibiotic prophylaxis with a first-generation cephalosporin to cover skin flora is both inexpensive and safe and that such practice should not be considered inappropriate. In the acute setting of a small bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated hernia, appropriate perioperative antibiotics should be given within 60 minutes of the initial skin incision.

Patients should be asked to void preoperatively. In most elective cases, a Foley catheter is not necessary.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with pneumatic compression devices starting prior to surgery and continuing in the recovery phase is now standard of care.

Anesthesia options for inguinal herniorrhaphy include general, spinal, and local anesthesia with or without intravenous sedation. Emergent cases of small bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated inguinal or femoral hernias will require general anesthesia.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with arms out on arm boards.

TECHNIQUES

The approach to the inguinal canal is the same for all anterior groin hernia repairs.

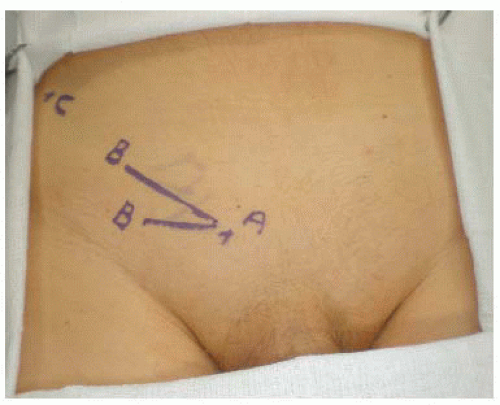

Gentle palpation of the inguinal area allows the identification of the spermatic cord. An oblique incision or incision along a skin crease or hairline centered around the cord structures is then made (FIG 1).

Using electrocautery, the soft tissue is dissected to the superficial epigastric vessels, which are ligated. The dissection is then carried down through Camper’s fascia and the more fibrous Scarpa’s fascia. The next layer is the transparent innominate fascia and the external oblique aponeurosis. Palpation along the external oblique aponeurosis moving laterally and inferiorly should exclude a femoral hernia.

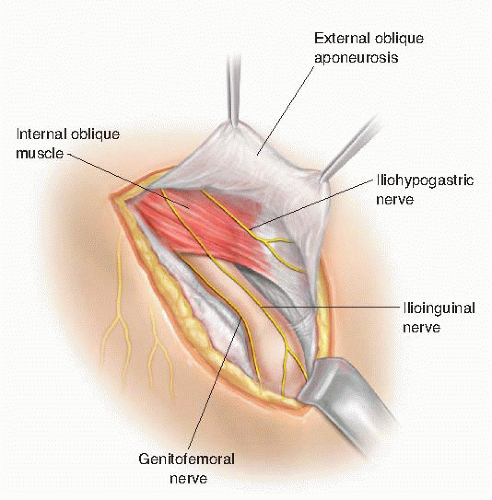

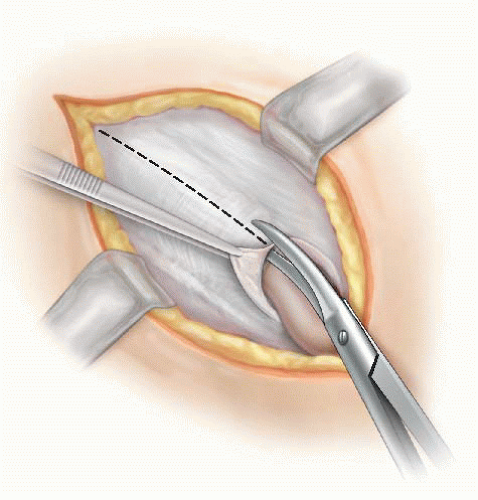

The external ring is identified and is covered with the external spermatic fascia, which is continuous with the innominate fascia. The external oblique aponeurosis is opened with a scissor, starting medial at the external ring and moving superior/lateral parallel to the inguinal ligament (FIG 2). Elevating the fascia and using a scissor protects the ilioinguinal nerve from sharp or thermal injury. The ilioinguinal nerve lies just below the aponeurosis of the external oblique and anterior to the cord. If injury to the nerve occurs, it is best divided and excised proximally, allowing the nerve to retract into the muscle or preperitoneal space.

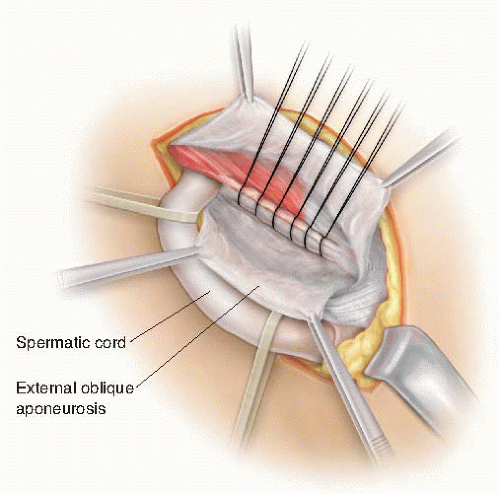

The medial and lateral external oblique flaps are then dissected free. Insertion of Weitlaner retractors below

the flaps greatly facilitates exposure of the spermatic cord. The iliohypogastric nerve can be identified running between the internal and external oblique superior and medial to the spermatic cord. It exits the external oblique medial and superior to the external ring (FIG 3).

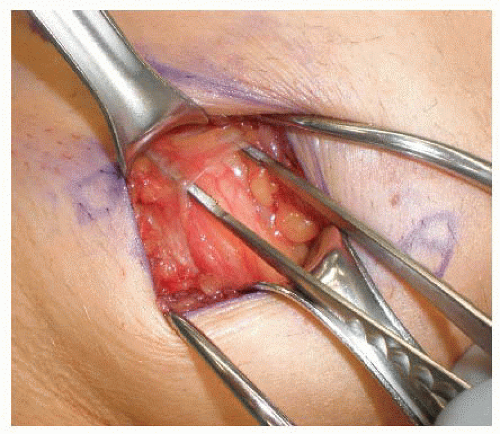

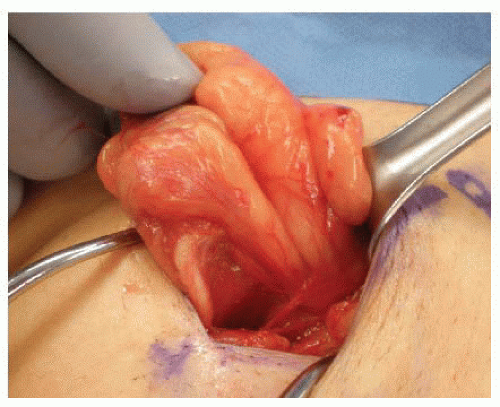

The spermatic cord is mobilized and isolated in the inguinal canal at the pubic tubercle but not medial to it (FIG 4). This will reduce the chance of damaging the posterior inguinal canal and any collateral circulation to the testes. A Penrose drain is placed around the cord structures and can be used to provide traction during dissection of the cord.

The spermatic cord is explored for evidence of an indirect hernia. The cremaster muscle fibers are not divided but are split parallel to the cord. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve lies posterior in the cord and is best preserved by splitting the cremasteric muscles. Inspection on the anterior medial aspect of the cord will identify an indirect hernia (FIG 5).

The indirect hernia sac is then dissected from the cord structures using sharp and blunt dissection. The sac is dissected down to the internal inguinal ring and freed from surrounding structures. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the vas deferens, which is closely associated with the sac proximally. The hernia sac is then reduced through the internal ring. The sac can also be transected and ligated. If ligated, the sac should be opened to assure that there is not a sliding component to the hernia.

FIG 2 • The external oblique is opened from the superficial ring toward the deep ring while avoiding injury to the ilioinguinal nerve.

FIG 4 • The isolation of the spermatic cord is done above the pubic tubercle to prevent injury to the inguinal floor.

In female patients, the round ligament can be completely transected, allowing for closure of the internal ring during repair.

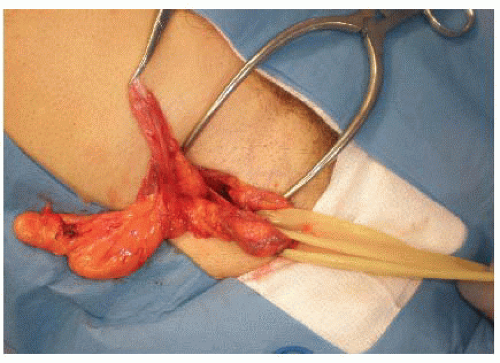

A cord “lipoma” is not a lipoma (suggesting growth of adipose tissue) but is rather extra or preperitoneal fat. It is usually associated with an indirect hernia but could also be present without an associated sac. Cord lipomas should be dissected free and resected as they can act as a lead point for a hernia sac (FIG 6).

A sliding hernia is an indirect hernia that has part of its sac made up of retroperitoneal viscus. This could be bladder, cecum, or sigmoid colon. The safest method of managing a sliding hernia is a safe dissection of the indirect sac and simple reduction back to the preperitoneal space. The danger with high ligation of an indirect hernia sac, without proper inspection of the sac, is injury to the bowel within a sliding hernia.

Following inspection of the spermatic cord and reduction of any indirect sac and excision of any preperitoneal fat, attention is turned to the posterior inguinal canal.

Gentle retraction of the spermatic cord will facilitate exposure. Any defects or weakness of the floor should be assessed. In large direct hernias, a purse-string suture around the defect or imbrications of the floor with figure-of-eight sutures will reduce the direct bulge, allowing one to work unencumbered by it.

BASSINI REPAIR

The Bassini repair is rarely performed today but remains the foundation for all hernia repairs. It is a primary tissue repair that consists of suturing of the transversus abdominis muscle, internal oblique muscle, and transversalis fascia medially to the inguinal ligament laterally.1,2 It is an option to consider in cases where contamination is likely and the use of mesh becomes contraindicated.

Technique

Bassini’s original description of the procedure included resection of the cremasteric fibers. Although still advocated by some, it is not routinely done.

After elevation and lateral retraction of the spermatic cord, the inguinal canal is carefully inspected for defects and weaknesses.

The muscular and aponeurotic arch formed by the lower fibers of the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique muscle is used to identify the medial edge of the repair.3 In his repair, Bassini opened the transversalis fascia,1 but most surgeons today would often omit this step and place the sutures between the aponeurotic arch and the deeper transversalis fascia to the inguinal ligament. If the anatomic layers are not clear, as in recurrent hernia surgery, opening the floor and clearly defining the anatomy will ensure the incorporation of the three anatomic layers medially: the internal oblique muscle, the transversus abdominis muscle, and the transversalis fascia.

If the decision is made to open the inguinal canal floor, it is done by incising the transversalis fascia from the pubic tubercle to the internal inguinal ring. Care should be taken not to injure the inferior epigastric vessels, which are directly posterior to the transversalis fascia. Once the transversalis fascia is opened and the undersurface of the fascial flaps is exposed, one can easily identify the three anatomic layers described earlier and more carefully inspect the femoral canal.

FIG 7 • If the transversalis fascia is opened in a Bassini repair, the iliopubic tract may be incorporated into the lateral stitch.

Once the muscular aponeurotic arch and the inguinal ligament are properly exposed and a femoral hernia is ruled out, single interrupted permanent polypropylene sutures are used to perform the repair. The first stitch is the most medial and should include the lateral edge of the rectus sheath if possible. It is placed from the rectus sheath and aponeurotic arch to the fascia overlying the pubic tubercle and not the inguinal ligament. This is an important technical point in order to reduce recurrence at the pubic tubercle, a common site.

Subsequent sutures should be placed from the muscular aponeurotic arch, incorporating all three layers, to the inguinal ligament. Medially, each suture is taken 2 cm from the edge of the arch. Laterally, the suture should incorporate few fibers of inguinal ligament, thus avoiding the underlying femoral vessels. Different fibers should be incorporated with each suture to avoid tearing the inguinal ligament. Upon reaching the internal inguinal ring, the ring is tightened, allowing the tip of a forceps to pass through the ring and avoiding strangulation of the cord structures.

If the transversalis fascia has been opened, the iliopubic tract will be identified. The medial stitch should first incorporate the iliopubic tract and then the inguinal ligament (FIG 7).

The spermatic cord is returned to its normal anatomic position, lying superior to the newly reconstructed inguinal floor, and closure of the superficial layers is performed in the standard fashion (FIG 8).

In order to decrease tissue tension after the repair is completed, a relaxing incision can be made vertically for few centimeters on the anterior rectus sheath parallel to the repair line. This will allow relaxation of the aponeurotic arch toward the inguinal ligament.

SHOULDICE REPAIR

After Bassini, the Shouldice repair is the most popular inguinal hernia tissue repair.4 It continues to be used as the primary inguinal hernia repair in the Shouldice clinic and by others who trained at the Shouldice clinic.5 It can also be used in situations where mesh is contraindicated such as in contaminated cases.

Technique

Like the Bassini repair, the Shouldice repair starts with a resection of the cremasteric muscle as an important step of the repair. Although some still advocate this step, we do not think that this adds to the durability of repair and it potentially exposes the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve to injury.

The transversalis fascia is opened from the medial aspect of the internal ring to the fascial thickening of Cooper’s ligament. This should be done with caution as the inferior epigastric vessels will be encountered just below the transversalis fascia. The opening of the transversalis fascia allows identification of all three layers of the posterior wall (transversalis abdominis muscle, internal oblique muscle, and transversalis fascia). Flaps of transversalis fascia are developed medially and laterally by carefully sweeping the underlying preperitoneal fat (FIG 9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree