Inguinal Hernia: Laparoscopic Approaches

Benjamin K. Poulose

Michael D. Holzman

Rebeccah B. Baucom

DEFINITION

Inguinal hernias can be divided into indirect, direct, and femoral based on location.

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons in the United States, with 750,000 to 800,000 cases annually.

Inguinal hernia will affect nearly 25% of men and less than 2% of women over their lifetime.

The majority of femoral hernias occur in women (around 70%), but indirect inguinal hernias are still the most common type of hernia in women.

Indirect inguinal hernias result from a patent processus vaginalis and are responsible for most pediatric inguinal hernias.

ANATOMY

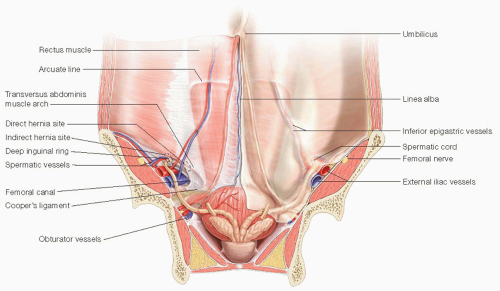

The myopectineal orifice includes both the inguinal and femoral regions. The inguinal ligament divides the myopectineal orifice into the inguinal region superiorly and the femoral region inferiorly.

The boundaries of the inguinal canal are as follows: anteriorly, the aponeurosis of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscle laterally; posteriorly, the transversalis fascia and the transversus abdominis muscle; superiorly, the arch formed by the internal oblique muscle; inferiorly, the inguinal ligament; medially, the aponeurosis of the external oblique and its insertion on the pubic symphysis (FIG 1).

An indirect hernia passes with the spermatic cord (or round ligament, in women) through the inguinal canal via the internal and external rings.

A direct hernia passes through the posterior wall of the canal (i.e., the transversalis fascia and transversus abdominis), medial to the inferior epigastric vessels, above the inguinal ligament. This region is considered Hesselbach’s triangle.

Femoral hernias pass through the femoral canal, medial to the femoral vessels, inferior to the inguinal ligament.

The nerves at risk for traction injury in most anterior inguinal hernia repairs include the ilioinguinal nerve, iliohypogastric nerve, and the genital and femoral branches of the genitofemoral nerve.

PATHOGENESIS

Indirect hernias occur as a result of a patent processus vaginalis and are congenital. The hernia involves a peritoneal sac passing through the inguinal canal alongside the spermatic cord or round ligament.

Direct hernias tend to occur secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure. Predisposing factors include chronic cough, constipation, straining and difficulty with urination, obesity, and ascites.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of untreated inguinal hernias is not fully known, although many believe that progression is inevitable. Traditionally, repair of all inguinal hernias has been recommended to prevent progression, hernia symptoms, and strangulation.

Watchful waiting is a reasonable strategy especially in men with minimal symptoms, as the rate of acute hernia incarceration with bowel obstruction, strangulation of intraabdominal contents, or both is less than 2 per 1,000 patient-years.1

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Most patients present with a groin bulge as their primary complaint. Over time, this tends to increase and may be associated with pain or discomfort in the groin, thigh, or testicle.

Some are asymptomatic and detected on physical exam by a primary care physician.

Significant pain at initial presentation, particularly if not accompanied by an obvious bulge, may not be due to hernia. Often, these patients will have chronic pain even after groin exploration.

Patients who develop progressive symptoms with increasing hernia size tend to have the best outcomes after surgical repair with significant improvement in pain.

Physical examination is the best way to diagnose inguinal hernias, and both sides should be evaluated for the presence of a hernia. The patient should be examined supine and upright, with a finger palpating the external ring while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. A bulge detected below the inguinal ligament in the medial thigh suggests a femoral hernia.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Adjunctive imaging studies are rarely required for diagnosis of inguinal hernia.

Ultrasound may be helpful but is dependent largely on the skill of the sonographer. Valsalva maneuvers should be employed, and the exam should be performed with the patient supine and upright.

Some inguinal hernias can be seen on computed tomography (CT), although small studies suggest that the sensitivity and specificity are only 85% and 65% to 85%, respectively. Therefore, if a hernia is not visualized on CT, the diagnosis is not ruled out.

The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without Valsalva is unclear but may be available at some centers. MRI is most useful in differentiating sports-related injuries from true inguinal hernias.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for a groin bulge includes hernia, lymphadenopathy, hydrocele, abscess, hematoma, femoral artery aneurysm, or undescended testicle.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Patients with minimally symptomatic hernias may be candidates for nonoperative management or watchful waiting.1 This approach entails follow-up after 6 months and annually by a care provider, along with instructions regarding the signs and symptoms of acute incarceration or strangulation.

Delay of repair for 6 months has been shown not to have an adverse effect on surgical outcomes.2

Patients who experience significant pain with activity, those who have prostatism or constipation, and those with overall good health status are likely to benefit most from surgical repair.3

After 2 years, about 25% of patients who are minimally symptomatic will develop worsening symptoms and request surgical repair.1

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Techniques for the laparoscopic management of inguinal hernia include the transabdominal properitoneal approach (TAPP) and the totally extraperitoneal (TEP) technique.

Laparoscopic repair is especially useful for recurrent or bilateral inguinal hernias.

A recent meta-analysis comparing open and laparoscopic repairs (TAPP and TEP) for primary unilateral hernias demonstrated that both laparoscopic approaches resulted in less chronic groin pain and numbness compared to open repair. TAPP and open repairs had a lower risk of recurrence compared to TEP. TAPP was associated with a higher risk of perioperative complications compared to open repair.4

Preoperative Planning

General anesthesia is usually required for laparoscopic repairs, whereas open repairs can be performed with the use of local anesthesia.

Immediately prior to surgery, the patient should be instructed to void or a Foley catheter should be placed. Most patients can adequately void preoperatively, precluding the need for a urinary catheter, which may increase the risk of urinary retention as well as infection.

For recurrent hernias, it is imperative that the surgeon review previous operative reports. In general, the approach used to repair a recurrence should use fresh surgical planes to facilitate the repair. For a previous open repair that has recurred, a laparoscopic approach is usually favored. If a mesh plug has been used, a TAPP approach may be significantly easier than TEP due to the high chance of peritoneal violation and need to debulk the plug.

For a previous laparoscopic repair that has recurred, an open approach may be easier to perform. Given the variety of laparoscopic inguinal hernia techniques used, many have found that repeat laparoscopic repair of a recurrence is possible in experienced hands.

Caution should be taken in patients with previous prostatectomy or entrance into the space of Retzius, which can make laparoscopic repair much more challenging. In these cases, serious consideration should be given to an anterior

approach. As with repairing laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair recurrences, a laparoscopic approach can be attempted, if deemed advantageous, by an experienced laparoscopic hernia surgeon.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with arms tucked and legs secured in order to prevent slippage with changes in table position during the procedure.

The surgeon stands on the contralateral side from the hernia being repaired.

TECHNIQUES

LAPAROSCOPIC TRANSABDOMINAL PROPERITONEAL INGUINAL HERNIA REPAIR

Establishment of Pneumoperitoneum and Port Placement

The first trocar is placed at the level of the umbilicus, typically beginning in the umbilicus and extending the incision inferiorly. Pneumoperitoneum can be established either with a Veress needle or by placing a 12-mm Hasson port.

Two 5-mm ports are then placed lateral to the rectus sheath approximately 1 to 2 cm above the level of the umbilicus (FIG 2). A 5-mm 30-degree laparoscopic is used and is placed in the port ipsilateral to the hernia. The surgeon uses the umbilical port and port contralateral to the hernia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree