Patient Story

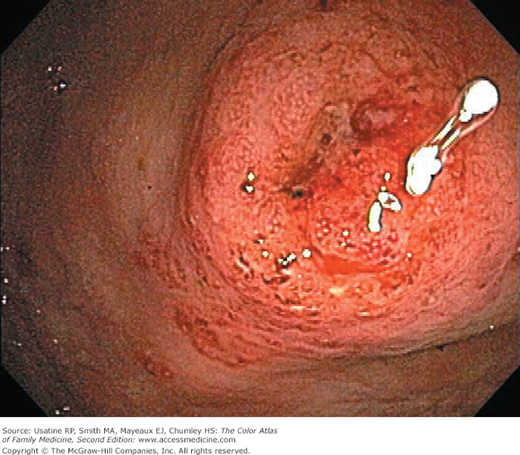

A 20-year-old man presents with several days of diarrhea with a small amount of rectal bleeding with each bowel movement. This is his second episode of bloody diarrhea; the first seemed to resolve after several days and occurred several weeks ago. He has cramps that occur with each bowel movement, but feels fine between bouts of diarrhea. He has no travel history outside of the United States. He is of Jewish descent and has a cousin with Crohn disease. Colonoscopy shows mucosal friability with superficial ulceration and exudates confined to the rectosigmoid colon, and he is diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (Figure 65-1).

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease. The intestinal inflammation in UC is usually confined to the mucosa and affects the rectum with or without parts or the entire colon (pancolitis) in an uninterrupted pattern. In Crohn disease, inflammation is often transmural and affects primarily the ileum and colon, often discontinuously. Crohn disease, however, can affect the entire GI tract from mouth to anus.

Epidemiology

- Incidence of UC in the West is 8 to 14 per 100,000 people and 6 to 15 per 100,000 people for Crohn disease.1 Prevalence for UC and Crohn disease in North America (one of the highest rates in the world) is 37.5 to 238 per 100,000 people and 44 to 201 per 100,000 people, respectively; IBD therefore affects an estimated 1.3 million people in the United States.1 Rates of IBD are increasing in both the West and in developing countries.1

- Age of onset is 30 to 40 years for UC and 20 to 30 years for Crohn disease. A bimodal distribution with a second peak at ages 60 to 70 years has been reported but not confirmed.1 Pediatric patients account for up to 20% of cases.

- Predilection for those of Jewish ancestry (especially Ashkenazi Jews) followed in order by non-Jewish whites and African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians.1

- Inheritance (polygenic) plays a role with a concordance of 20% in monozygous twins and a risk of 10% in first-degree relatives of an incidence case.2

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Unknown etiology—Current theory is that colitis is an inappropriate response to microbial gut flora or a lack of regulation of intestinal immune cells in a genetically susceptible host with failure of the normal suppression of the immune response and tissue repair.2,3

- Genetic regions containing nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2; encodes an intracellular sensor of peptidoglycan), autophagy genes (regulate clearing of intracellular components like organelles), and components of the interleukin-23-type 17 helper T-cell (Th17) pathway are associated with IBD; the autophagy gene, ATG16L1, is associated with Crohn disease.3

- Multiple bowel pathogens (e.g., Salmonella, Shigella species, and Campylobacter) may trigger UC. This is supported by a large cohort study where the hazard ratio of developing IBD was 2.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7 to 3.3) in the group who experienced a bout of infectious gastroenteritis compared with the control group; the excess risk was greatest during the first year after the infective episode.4 People with IBD also have depletion and reduced diversity of some members of the mucosa-associated bacterial phyla, but it is not known whether this is causal or secondary to inflammation.3

- Other abnormalities found in patients with IBD include increased permeability between mucosal epithelial cells, defective regulation of intercellular junctions, infiltration into the lamina propria of innate (e.g., neutrophils) and adaptive (B and T cells) immune cells with increased production of tumor necrosis factor α and increased numbers of CD4+ T cells, dysregulation of intestinal CD4+ T-cell subgroups, and the presence of circulating antimicrobial antibodies (e.g., antiflagellin antibodies).3 Many of the therapeutic approaches target these areas.

- Psychological factors (e.g., major life change, daily stressors) are associated with worsening symptoms.

- Patients with longstanding UC are at higher risk of developing colon dysplasia and cancer; this is believed to be a developmental sequence (see “Prognosis” below).

Risk Factors

Diagnosis

The diagnosis depends on the clinical evaluation, sigmoid appearance, histology, and a negative stool for bacteria, Clostridium difficile toxin, and ova and parasites.2

- Major symptoms of UC—Diarrhea, rectal bleeding, tenesmus (i.e., urgency with a feeling of incomplete evacuation), passage of mucus, and cramping abdominal pain.

- Symptoms in patients with Crohn disease depend on the location of disease; patients become symptomatic when lesions are extensive or distal (e.g., colitis), systemic inflammatory reaction is present, or when disease is complicated by stricture, abscess, or fistula. Gross blood and mucus in the stool are less frequent and systemic symptoms, extracolonic features, pain, perineal disease, and obstruction are more common.2 There is no relationship between symptoms and anatomic damage.1

- UC is classified by severity based on the clinical picture and results of endoscopy;5 treatment is based on disease classification.

- Mild: Less than 4 stools per day, with or without blood, no signs of systemic toxicity, and a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

- Moderate: More than 4 stools per day but with minimal signs of toxicity.

- Severe: More than 6 bloody stools per day, and evidence of toxicity demonstrated by fever, tachycardia, anemia, and elevated ESR.

- Fulminant: May have more than 10 bowel movements daily, continuous bleeding, toxicity, abdominal tenderness and distention, a blood transfusion requirement, and colonic dilation on abdominal plain films.

- Mild: Less than 4 stools per day, with or without blood, no signs of systemic toxicity, and a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

- Extraintestinal manifestations are present in 25% to 40% of patients with IBD, but are more common in Crohn disease than UC:2,6

- Dermatologic (2% to 34%)—Erythema nodosum (10%) that correlates with disease activity and pyogenic gangrenosum (pustule that spreads concentrically and ulcerates surrounded by violaceous borders) in 1% to 12% of patients.2

- Rheumatologic—Peripheral arthritis (5% to 20%), spondylitis (1% to 26%, but nearly all of those positive for human leukocyte antigen B27), and symmetric sacroiliitis (<10%).

- Ocular—Conjunctivitis, uveitis, iritis, and episcleritis (0.3% to 5%)6

- Hepatobiliary—The most serious complication in this category is primary sclerosing cholangitis; although 75% of patients with this disease have UC, only 5% of those with UC and 2% of patients with Crohn disease develop it.6 Hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) and cholelithiasis can also occur.

- Cardiovascular—Increased risk of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and stroke (because of a hypercoagulable state from thrombocytosis and gut losses of antithrombin III among other factors); endocarditis; myocarditis; and pleuropericarditis.2

- Bone—Osteoporosis and osteomalacia from multiple causes including medications, reduced physical activity, inflammatory-mediated bone resorption, vitamin D deficiency, and calcium and magnesium malabsorption. Fracture risk in patients with IBD is 1 per 100 patient-years (40% higher than the general population).6

- Renal—Nephrolithiasis, obstructive uropathy, and fistulization of the urinary tract occur in 6% to 23%.6

- Dermatologic (2% to 34%)—Erythema nodosum (10%) that correlates with disease activity and pyogenic gangrenosum (pustule that spreads concentrically and ulcerates surrounded by violaceous borders) in 1% to 12% of patients.2

- Extraintestinal manifestations may occur prior to the diagnosis of IBD. For example, 10% to 30% of patients with IBD-related arthritis develop arthritis prior to IBD diagnosis.6

- Severe complications include toxic colitis (15% initially present with catastrophic illness), massive hemorrhage (1% of those with severe attacks), toxic megacolon (i.e., transverse colon diameter >5 to 6 cm) (5% of attacks; may be triggered by electrolyte abnormalities and narcotics), and bowel obstruction (caused by strictures and occurring in 10% of patients).1

- On endoscopy in patients with Crohn disease, rectal sparing is frequent and cobblestoning of the mucosa is often seen. Small bowel involvement is seen on imaging in addition to segmental colitis and frequent strictures (Figure 65-5).

- Diagnosis is changed from UC to Crohn disease over time in 5% to 10% of patients.7

- At presentation, about a third of patients with UC have disease localized to the rectum, another third have disease present in the colorectum distal to the splenic flexure, and the remainder with disease proximal to the splenic flexure; pancolitis is present in one quarter.1 Adults appear to always have rectal involvement, which is not the case for children. Over time (20 years), half will have pancolitis (Figure 65-1).8

- In patients with Crohn disease, lesions occur in equal proportions in the ileum, colon, or both; 10% to 15% have upper GI lesions, 20% to 30% present with perianal lesions and about half eventually develop perianal disease. Fifteen percent to 20% of patients have or have had a fistula.1

- Acute disease can result in a rise of acute phase reactants (e.g., C-reactive protein) and elevated ESR (rare in patients with just proctitis). C-reactive protein is elevated in nearly all patients with Crohn disease and in approximately half the patients with UC.9

- Obtain hemoglobin (to assess for anemia) and platelets (to assess for reactive thrombocytosis).

- Of the biomarkers available to detect IBD, fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are most commonly used.9 The former is an indirect measure of neutrophil infiltrate in the bowel mucosa and the later is an iron-binding protein secreted by mucosal membranes and found in neutrophil granules and serum. Although the optimal threshold value for calprotectin in detecting IBD is unknown, a study of adult patients suspected of having IBD based on clinical evaluation reported a sensitivity and specificity of the test of 93% and 96%, respectively.10 Test characteristics for lactoferrin are lower at 80% and 82%.

- Stool should be examined to rule out infectious causes including C. difficile; the incidence of C. difficile is increasing in patients with UC and is associated with a more severe course in those with IBD.11

Imaging has become more important for patients with IBD, not only for diagnosis in symptomatic patients but for early detection and treatment of inflammation in asymptomatic patients with Crohn disease and for monitoring inflammation and disease complications.12

- Colonoscopy with ileoscopy and mucosal biopsy should be performed in the evaluation of IBD and for differentiating UC from Crohn disease (Figures 65-1, 65-2, 65-3, 65-4, 65-5).13 SOR B It is the best test for detection of colonic inflammation.5,10

- Colonoscopy can show pseudopolyps in both active UC (Figure 65-3) and inactive UC (Figure 65-4). Risks of ileocolonoscopy include perforation, limited small bowel evaluation and inability to stage penetrating disease.12

- Capsule endoscopy (CE) is a less-invasive technique for evaluating the small intestine in patients with Crohn disease and is more sensitive than radiologic and endoscopic procedures for detecting small bowel lesions and mucosal inflammation.12,13 SOR B CE should not be performed in patients with Crohn disease known or suspected to have a high-grade stricture. In that case, consider CT enterography.13 The major risk is retention.12

- In patients with initial presentation of symptomatic Crohn disease, the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends CT enterography.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree