5 Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases remain the greatest killers of humankind. Infection differs from other disease processes in that it comprises an interaction between the human body and another organism. Infection has been part of our evolution, evident by the development of a complex immune system. All body systems are susceptible to infection, and understanding infection and its management is integral to clinical care in every medical subspecialty.

PRINCIPLES OF INFECTIOUS DISEASE

The interaction of viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa with the human body is:

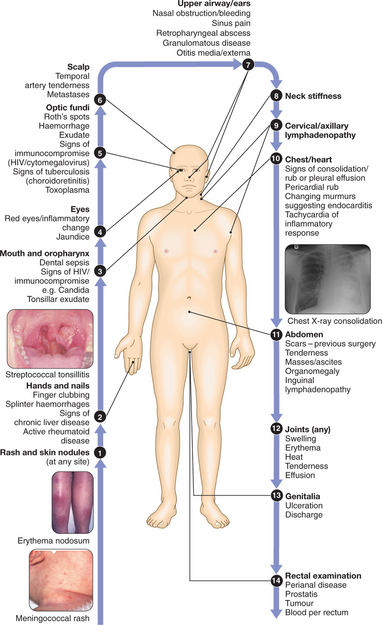

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE PYREXIAL PATIENT

RESERVOIRS OF INFECTION

MANAGEMENT OF INFECTION

Infectious disease results from the interaction between the microorganism and the immune system. The management of infection therefore requires both action to inhibit the microorganism and limitation of the host’s inflammatory response. This may involve more than simple antimicrobial therapy; indeed, antibiotics are not required for all infections.

PREVENTION OF INFECTION

INFECTION CONTROL

OUTBREAK CONTROL

An outbreak of infection is defined as two or more linked cases of an infectious disease occurring simultaneously or unexpectedly, or the occurrence of any disease clearly in excess of normal expectancy. Many countries have systems of compulsory notification of contagious conditions to public health authorities so that outbreaks can be recognised and appropriate measures put in place to control the further spread of the condition. These measures may include:

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN INFECTIOUS DISEASES

PYREXIA OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN (PUO)

PUO is a common presenting problem and may be defined as a consistently elevated body temperature of >37.5°C persisting for >2 wks with no diagnosis after initial investigation. Many causes of PUO are listed in Box 5.1. Two or more causes of fever may coexist.

5.1 AETIOLOGY OF PUO IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES ![]()

Infections (30%)

The following account applies to immunocompetent individuals in developed countries with community-acquired PUO. Infection will account for a higher percentage of PUO in developing countries. Fever in old age merits special attention (Box 5.2).

5.2 FEVER IN OLD AGE ![]()

Investigations and management

5.4 USEFUL SEROLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PUO IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES ![]()

| Viral | CMV, hepatitis A, B and C, infectious mononucleosis, erythrovirus, HIV, if travel history: Arbovirus |

| Bacterial | Chlamydia, leptospirosis, Q fever, Lyme disease, brucellosis, Yersinia, Mycoplasma, Streptococcus, syphilis |

| If travel history | Rickettsia, relapsing fever, melioidosis, bartonellosis |

| Fungal | Cryptococcosis (antigen detection) |

| If travel history | Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis |

| Protozoal and parasitic | Toxoplasmosis |

| If travel history | Schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, amoebiasis, trypanosomiasis |

The role of biopsies in investigation

Temporal artery biopsy: Should be considered in patients over the age of 50, even if the ESR is not significantly elevated. Since arteritis is patchy, diagnostic yield is increased if a 5 cm section of artery is biopsied.

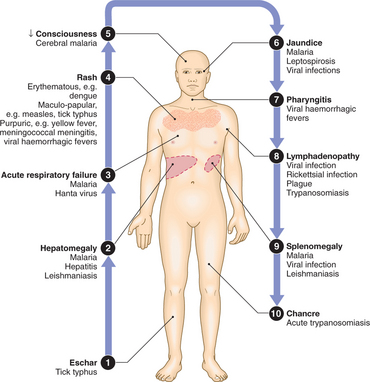

FEVER IN THE RETURNING TRAVELLER/TROPICAL RESIDENT

Vaccinations and prophylaxis

Investigations

Initial investigations in all settings should start with thick and thin blood films for malaria parasites, FBC, urinalysis and CXR if indicated. Box 5.5 gives the diagnoses that should be considered in acute fever with no localising signs, grouped according to differential WCC.

5.5 DIFFERENTIAL WCC: ACUTE FEVER IN THE ABSENCE OF LOCALISING SIGNS ![]()

| WCC differential | Potential diagnoses | Further investigations |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil leucocytosis | Bacterial sepsis | Blood culture |

| Leptospira and Borrelia | ||

| Leptospirosis | Culture of blood and urine, serology | |

| Tick-borne relapsing fever | Blood film | |

| Louse-borne relapsing fever | Blood film | |

| Amoebic liver abscess | USS | |

| Normal WCC and differential | Typhoid fever | Blood, stool and culture |

| Typhus | Serology | |

| Arboviral infection | Serology (PCR and viral culture) | |

| Lymphocytosis | Viral fevers | Serology |

| Infectious mononucleosis | Monospot test | |

| Rickettsial fevers | Serology |

FEVER ASSOCIATED WITH A RASH

Many infective processes produce skin manifestations, either as a result of infection or a toxin or as part of an immune reaction. Different patterns of rash associated with fever are summarised in Box 5.6. Although the combination of fever and rash frequently indicates infection in the mind of the patient, there are many non-infectious causes of this combination, such as the autoimmune vasculitides.

5.6 PATTERNS OF RASH ASSOCIATED WITH INFECTION ![]()

Vesicular/pustular

Erythematous

FEVER IN THE INJECTION DRUG-USER

Clinical assessment

FEVER IN THE NEUTROPENIC PATIENT

Neutropenia is defined as a neutrophil count of <1.5 × 109/l.

Patients with neutropenia, particularly <1.0 × 109/l, either from drug toxicity (including chemotherapy for cancer) or from marrow invasion or failure, are particularly prone to bacterial infections. Gram-positive organisms have now superseded Gram-negative infections as the most common pathogens in this condition, particularly where any line infection or indwelling catheter is present. Specimens such as blood cultures, swabs and urine samples should be taken and empirical antibiotic therapy started, commonly with a broad-spectrum penicillin and an aminoglycoside (e.g. piperacillin/tazobactam + gentamicin). Any potential nidus of infection such as a urinary or vascular catheter should be removed and, if necessary, replaced.

ACUTE DIARRHOEA

Acute diarrhoea is an extremely common presenting problem, and may result from both infectious and non-infectious causes (Box 5.7). Infectious diarrhoea is caused by faecal–oral transmission of bacterial toxins, viruses, bacteria or protozoal organisms. Psychological or physical stress may also precipitate diarrhoea. Occasionally, diarrhoea may be the presenting feature of another systemic illness, such as a lobar pneumonia.

Infectious

FOOD POISONING AND GASTROENTERITIS

Acute gastroenteritis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in both developing and developed countries. Causative organisms are listed in Boxes 5.7 and 5.8. The clinical features of food-borne disease depend on the organism; for example, enterotoxic organisms produce vomiting and ‘secretory’ watery diarrhoea. Organisms that invade the mucosa, such as Shigella and Salmonella, have longer incubation periods and may cause systemic upset and blood in the stool.

ASSESSMENT OF THE PATIENT WITH ACUTE DIARRHOEA

Box 5.9 shows markers of severity and coexisting conditions which increase the likelihood that intensive treatment (e.g. antimicrobials) will be needed.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE DIARRHOEA

Antibiotics/antimicrobial therapy: Not generally used, except in severe cases (Box 5.9). Have a high threshold for their use and discuss with the infectious diseases department.

Adjunctive antidiarrhoeal therapy: Anti-motility drugs are not generally recommended and may indeed prolong or worsen the course of an acute infective gastroenteritis.

EOSINOPHILIA

Eosinophilia is associated both with parasite infections (particularly helminths) and with allergic reactions. Eosinophils have an important role in mediating antibody-dependent damage to helminths. Anybody with an eosinophil count >0.4 × 109 should be investigated for both parasitic and non-parasitic causes of eosinophilia (Box 5.10). Eosinophilia is not a typical feature in malaria, amoebiasis, leishmaniasis, leprosy or tapeworm infections other than cysticercosis.

Clinical assessment

5.11 CLINICAL FEATURES ASSOCIATED WITH HELMINTHIC INFECTIONS AND EOSINOPHILIA ![]()

| Urticarial rashes | Strongyloidiasis, onchocerciasis, fascioliasis, hydatid disease, trichinosis |

| Cutaneous larva migrans | Ancylostoma braziliense |

| Dermatitis | Onchocerciasis |

| Migratory subcutaneous swellings | Loiasis, gnathostomiasis |

| Lymphangitis, orchitis | Lymphatic filariasis |

| Myositis | Trichinosis, cysticercosis |

| Febrile hepatosplenomegaly | Schistosomiasis, toxocariasis |

| Pneumonitis | Migratory stage of larval helminths (Löffler’s syndrome), lymphatic filariasis (tropical pulmonary eosinophilia), systemic strongyloidiasis |

| Enteritis and colitis | Strongyloidiasis, capillariasis, trichinosis |

| Meningitis | Angiostrongyliasis, strongyloidiasis |

Investigations

Direct visualisation of adult worms, larvae or ova provides the best evidence. Box 5.12 lists the initial investigations for eosinophilia.

5.12 INITIAL INVESTIGATION OF EOSINOPHILIA ![]()

| Investigation | Pathogens sought |

|---|---|

| Stool microscopy | Ova, cysts and parasites |

| Terminal urine | Ova of Schistosoma haematobium |

| Duodenal aspirate | Filariform larvae of Strongyloides, liver fluke ova |

| Day bloods | Microfilariae Brugia malayi, Loa loa |

| Night bloods | Microfilariae Wuchereria bancrofti |

| Skin snips | Onchocerca volvulus |

| Serology | Schistosoma, Filaria, Strongyloides, hydatid, trichinosis etc. |

SKIN CONDITIONS IN THE RETURNING TRAVELLER/TROPICAL RESIDENT

CUTANEOUS LARVA MIGRANS (CLM)

CLM is the most common linear lesion seen in travellers. Intensely pruritic, linear, serpiginous lesions result from the larval migration of the dog hookworm (Ancylostoma caninum). The track migrates across the skin at a rate of 2–3 cm/day. Most patients have recently visited a beach where the affected part (foot, elbows, buttocks or breast) was exposed. The diagnosis is clinical, and treatment consists of topical application of 15% tiabendazole cream 12-hourly, or a single systemic dose of albendazole or ivermectin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree