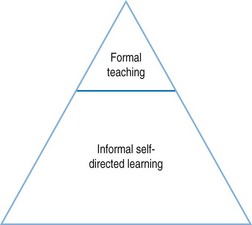

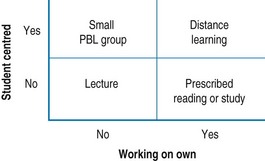

Chapter 19 In this chapter we will consider: • what we mean by independent learning and study skills • the important role they play in any curriculum • component skills in self study • the development of a study plan • the effective use of learning resources for independent study • the teacher’s role in independent learning • how the student can review prior learning effectively • how the student can undertake self-assessment • Students learn on their own. • Students have a measure of control over their own learning, in that they choose: • Students may be encouraged to develop their personal study plans (Challis 2000). • Differing needs of individual students are recognized and responded to appropriately. • Learning is supported by learning resources and study guides prepared specifically for this purpose • The role of the teacher changes from transmitter of information to manager of the learning process: a more demanding but a more rewarding role (Harden & Crosby 2000). • Independent learning: emphasizes that students work on their own to meet their own learning needs. • Self-managed learning, self-directed learning or self-regulated learning: emphasizes that students have an element of control over their own learning, with responsibility for diagnosis of learning needs, identifying resources and assessing the degree of learning by themselves. Implicit in this approach is that students have a clear understanding of the intended learning outcomes. • Resource-based learning: emphasizes the use of resource material in print or multimedia format as a basis for students’ learning and the freedom this gives the students. • ‘Just-for-you’ or flexible learning: emphasizes the wide range of learning opportunities offered to students and flexibility in responding to individual student needs and aspirations. • Open learning: is often used interchangeably with flexible learning. It emphasizes the provision of greater access for students to their choice of education. • E-learning: learning is facilitated by information and communication technology. • Distance learning: emphasizes that students work on their own at a distance from their teacher. Implicit in this approach is that the teacher interacts with students at a distance and facilitates the students’ learning. • ‘Just-in-time’ learning: resources are made available to learners when required. This facilitates ‘on-the-job’ learning and the integration of theory and practice. The two ideas underpinning the above concepts are: Both these features are absent in the lecture but present in independent learning (Fig. 19.1). • learning with understanding (deep learning), leading to long-term retention, rather than through rote (surface) learning, which is likely to result in short-term retention • seeking and retrieving information from an increasing variety of resources • critically reviewing what is read, rather than blindly accepting the written word • integrating new learning with existing knowledge by seeking links between them, and dealing with dissonance • assessing oneself on learning that has occurred to ensure that it can be remembered and applied to situations likely to be encountered in professional practice. The independent learner who is properly guided has the opportunity to develop these component skills while in medical school, while adopting a more active approach to learning. Students adopt a deep rather than a superficial approach to learning and search for an understanding of the subject rather than just reproducing what they have learned. They are encouraged to think rather than just recall facts. A learning approach does not describe a particular attribute of the student, but a relationship between the learner and the learning task (Ramsden 1987). Study skill courses should focus on developing students’ awareness of these approaches so that they could select that which is most suited to a given learning task. Superficial reading of text does not guarantee that what is read, and even understood, will be retained in long-term memory. While the most efficient reader may be the ‘one who can gather the most amount of information from the printed page in the least amount of time’ (Wilcox 1958), he or she may not be the most effective learner, as much of that information may be retained for only a short time. The reflective process involved in the deep approach to learning may, ostensibly, be more time-consuming. However, longer retention of learning makes this approach more effective in the long term. One reason why students complain of the tedious nature of basic science courses may be the lack of time and opportunity for reflection. Students must develop the practice of reflecting on the subject matter, connecting it with what they already know and summarizing new learning in their own words. Few would disagree that the attributes and study skills we would desire in a medical student are those embedded in the deep approach to learning. However, many curricula are planned and implemented in ways that promote surface or strategic approaches (Stiernborg & Bandaranayake 1996). The surge of curricula adopting problem-based learning to varying extents favours the deep approach (Newble & Clarke 1987), though the nature of the curriculum does not necessarily dictate the manner in which students undertake self-study in that curriculum. There is no reason, however, for not inculcating a deep approach even in the more conventional curricula. Students accustomed to surface learning may have initial difficulty adopting a deep approach. Effective ways of reflecting on newly learned material are writing essays, discussion with peers, teaching others and entertaining questions. The adoption of an independent learning approach encourages these needs to be recognized and allows for learner choice in terms of content, learning strategy and rates of learning (Fig. 19.2). In ‘just-for-you’ learning the learning programme is customized to the needs of the individual student or doctor. • individual preferences and style • practicalities of a given situation • priorities in the purpose of learning

Independent learning and study skills

Introduction

What are independent learning and study skills?

Why is independent learning important?

Active learning

The needs of the individual learner

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine