Incisional Hernia Repair: Abdominal Wall Reconstruction Options

Michael J. Rosen

DEFINITION

The field of abdominal wall reconstruction has seen significant advances in the past decade. A resurgence in the concept of recreating a functional dynamic abdominal wall through reconstructing the linea alba and restoring normal anatomy of the abdominal wall unit has fostered several innovative techniques to achieve these goals. The foundation for much of our understanding of abdominal wall reconstruction can be linked to pioneering surgeons such as Oscar Ramirez, Renee Stoppa, and Jean Rives. These reconstructive surgeons brought forth the concepts of performing fascial releases of the anterior abdominal wall compartments to provide advancement of the midline fascia. Although each of these surgeons and several of the newer techniques that will be described in this chapter differ in the exact mechanism in which fascial advancement is obtained, the underlying concept of achieving fascial advancement to reconstruct the midline is a constant.

When considering which approach is indicated for reconstructing the abdominal defect that the surgeon is faced with, it is helpful to provide general categories of the various abdominal wall reconstructive techniques. In the authors’ opinion, the most clinically relevant classification scheme is based on preservation of the anterior abdominal wall neurovascular blood supply and the need to raise large lipocutaneous flaps to gain access to the lateral abdominal wall. In general, minimally invasive approaches preserve the abdominal wall blood supply and avoid large skin flaps. Examples of such techniques include endoscopic component separation, posterior component separation, and periumbilical perforator sparing approaches, whereas, the standard open approach does not typically preserve the anterior abdominal wall blood supply.

This chapter will focus on some of the more advanced reconstructive techniques to repair large abdominal wall defects. Prior to discussing each of these approaches, it is imperative to understand that not all ventral hernia repairs will require these approaches. In fact, most abdominal wall defects less than 10 to 15 cm in maximal width can be repaired using a standard Rives-Stoppa-Wantz approach. This technique will be described in detail in another chapter in this textbook. In the authors’ opinion, this approach should always be initially considered prior to moving on to more advanced techniques.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

When planning an abdominal wall reconstruction, the most important first step is to clarify patient’s expectations for a successful outcome as well as the surgeon’s. Not all defects, particularly in the setting of contamination or infection, can or should be repaired in a single setting. Often, the initial attempt at clearing the infectious source or reconstructing the gastrointestinal (GI) tract takes precedence and formal reconstruction should be delayed. In these cases, the patient should understand that they will likely have a ventral hernia at the end of the procedure that eventually will need to be repaired.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Basic cardiac and pulmonary risk stratification are essential.

Skin preparation is critical, and an experienced wound care nurse is invaluable. Treating any subcutaneous cellulitis or breakdown can significantly improve soft tissue coverage at the time of formal reconstruction.

Optimization of nutritional status is also important. This can include supplemental, enteral, or parenteral feeding when necessary. It is also important to point out that patients with an ongoing infectious nidus, particularly infected synthetic mesh, can be very difficult to obtain a positive nitrogen balance.

Many patients with large ventral hernias also suffer from morbid obesity. The ideal approach to managing obesity in the setting of a complex ventral hernia is challenging. No doubt, substantial weight loss prior to surgical intervention is optimal. However, the best approach is unclear, but options include medically supervised weight loss or bariatric surgery. This can be particularly challenging in symptomatic incarcerated hernias in which there is little time to achieve or obtain clearance for weight loss surgery.

Preoperative smoking cessation is mandatory in our practice prior to complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Smoking has been clearly linked to impaired wound healing and in the author’s opinion is an absolute contraindication to complex abdominal wall reconstruction.

Obtaining and reviewing all old operative records is extremely important. Understanding what type of mesh and in what layer in the abdominal wall it was placed can help guide your approach. In addition, it is important to clarify if one of the lateral abdominal wall muscles were already released because it can lead to lateral abdominal wall laxity if it is rereleased. Likewise, the surgeon might choose another muscle to release to access an undissected plane.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Routine radiologic imaging with an abdominal-pelvic computed axial tomography (CAT) scan is particularly useful in complex ventral hernia repairs. These scans can provide valuable information as to the size of the defect and presence of loss of domain, the absence or destruction of important components of the abdominal wall, and the presence of remnant prosthetic materials.

More advanced radiologic imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or angiogram to look for periumbilical perforator vessels is not routinely performed in our practice.

Preoperative antibiotic and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis is routinely given. Typically, a first-generation cephalosporin will suffice, but in cases of prior or active methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, Vancomycin is added.

Nasogastric tube decompression and Foley catheters are routinely inserted.

Perioperative anesthesia management is critical to success in large abdominal wall reconstructions. It is important that the patient remains completely relaxed during the procedure as this greatly improves exposure of the abdominal wall. In addition, in larger abdominal wall reconstruction, there is often some level of compartment syndrome at the conclusion of the procedure. It is important to keep these patients intubated for a 24- to 48-hour period until their airway pressures normalize.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

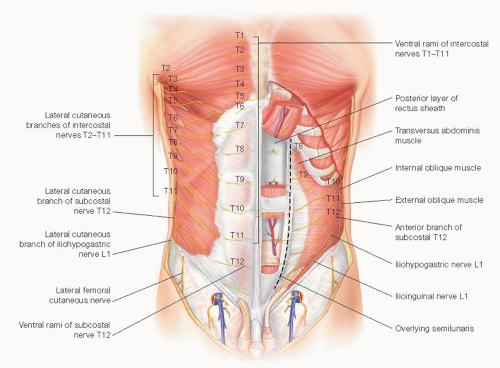

As with any hernia repair, it is critically important that the surgeon has a firm understanding of the anatomy of the abdominal wall prior to manipulation. The abdominal wall is basically composed of the two rectus muscles running longitudinally and the three lateral muscles on each side of the abdominal wall. Each performs a valuable function for the abdominal wall, and any disruption can cause impairment in core physiology. Understanding the neurovascular anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall is particularly important for optimizing the results of each of these approaches. The rectus muscle receives its innervation from the T7-T11 intercostal nerve routes. These nerves run above the transversus abdominis and below the internal oblique muscles in the lateral abdominal wall. They penetrate the linea semilunaris and segmentally innervate the rectus muscle. It is very important to preserve these nerves in any reconstruction; otherwise, the rectus muscle will atrophy and prevent any hope for a functional abdominal wall (FIG 1). One important consideration for a posterior component separation is that the transversus abdominis muscle actually forms the posterior sheath of the rectus muscle in the upper two-thirds of the abdomen.

FIG 1 • Innervation of the anterior abdominal wall. Note the intercostal nerves run in the lateral abdominal wall in between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle.

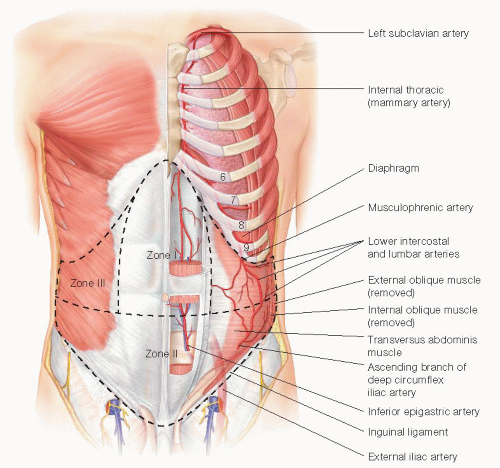

The blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall is slightly more complex (FIG 2). The rectus muscle receives its blood supply both laterally from the intercostal vessels and from a superior and inferior branch of the inferior epigastric vessel. The blood

supply to the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the midline is also important to understand to limit ischemic problems during reconstruction. The skin does receive some limited supply from the lateral intercostal vessels, but the majority comes from deep inferior epigastric perforator vessels. These vessels typically lie within 5 cm cephalad and caudad to the umbilicus. This relationship is particularly useful when performing a periumbilical perforator sparing component separation.

FIG 2 • Blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall. Note location of the medial row of perforators off the inferior epigastric providing blood supply to the medial aspect of the skin. |

Positioning

Regardless of the abdominal wall reconstructive technique chosen, some basic technical aspects remain constant. A wide surgical preparation including the entire abdomen, lower chest, and upper legs is performed with a chlorhexidine solution. All stoma sites are oversewn to minimize spillage. An iodine-impregnated dressing is routinely applied to cover the entire abdominal wall.

TECHNIQUES

INCISION

The surgical incision is typically performed in a midline fashion and all other old scars or skin ulcerations are completely excised.

ADHESIOLYSIS

The abdominal cavity is entered and a complete adhesiolysis is performed to free up the entire abdominal wall all the way to the gutters. This step is critical, as the abdominal wall will be limited in its mobility if it remains fixated to the viscera.

CONCOMITANT PROCEDURES AND REMOVAL OF ALL FOREIGN MATERIAL

Any concomitant GI surgery is completed and all prior synthetic material is removed from the abdominal wall. In our opinion, removing prior synthetic material allows the new prosthetic to actually grow into the abdominal wall and reduces seromas and mesh infections. After the intraperitoneal portion of the procedure is completed, a countable towel is placed over the abdominal viscera to prevent inadvertent injury during dissection of the abdominal wall.

POSTERIOR COMPONENT SEPARATION TECHNIQUE

A posterior component separation is basically an extension of the standard Rives-Stoppa-Wantz repair.

The initial procedure begins in a similar fashion. The linea alba is identified and grasped with Kocher clamps. To avoid confusion and misidentification of appropriate planes, the clamps must be placed on the medial edge of the rectus muscle and not on the hernia sac. If the clamps are on the hernia sac, the dissection will proceed in a subcutaneous plane. Next, an incision of the posterior sheath is made approximately 1 cm off the linea alba. It is important to identify the rectus muscle, which will avoid creating a subcutaneous or preperitoneal plane of dissection (FIG 3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree