Incisional Hernia: Open Approaches

Mark D. Sawyer

Michael G. Sarr

DEFINITION

An incisional hernia is a defect in the musculoaponeurotic layer of the abdominal wall occurring at the site of a prior incision. The sine qua non of any hernia is the presence of a fascial defect. Typically, a hernia is a protrusion of intraperitoneal abdominal contents through the defect, usually contained within a “sac” of peritoneum and covered with skin and perhaps subcutaneous fat. In certain circumstances such as the sequelae of an open abdomen, there may not be a true peritoneal sac nor a cutaneous cover.

There are certain circumstances in which a pseudohernia can mimic a true hernia. Flank incisions can denervate the lateral abdominal wall, causing flaccidity and an outward bulge appearing to be a “hernia,” even though the musculoaponeurotic layers are intact. Diastasis of the rectus muscles will also lead to a bulge especially on straining, but in both these circumstances, there is no actual defect in this musculoaponeurotic layer.

Incisional hernias are classified as incarcerated when the contents of the hernia sac cannot be reduced back into the confines of the peritoneal cavity and strangulated when incarceration leads to vascular compromise and ischemia of the incarcerated contents. Strangulated contents may be salvageable if reduction can be accomplished prior to irreversible ischemia and necrosis.

Incisional herniorrhaphies are designed to obliterate the musculoaponeurotic defect and restore continuity to the abdominal wall. This process may be accomplished in a number of ways but fall into three basic categories: (1) A primary repair with reapposition of the separated musculoaponeurotic edges is the simplest type of repair; (2) synthetic and biologic prostheses to restore abdominal wall continuity without primary apposition of the musculoaponeurotic layers, covering the defect in a bridging fashion with a “patch.” Generally, repairs in this fashion are performed as an underlay or overlay with a substantial amount of overlap beyond the musculoaponeurotic edge (usually ≥5 cm) because sewing the prosthesis directly to the edges leads to an unacceptably high rate of hernia recurrence; and (3) a component separation technique, which are extensive, anterior or posterior lateral relaxing incisions to allow for greater tissue mobility, medialization of the rectus muscles, and decreased tension. The component separation is often reinforced using synthetic or biologic prostheses as underlays or overlays.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of incisional hernias involves anything else that could cause a mass effect of the abdominal wall.

Pseudohernias arising from flank incisions and diastasis recti may be mistaken for true hernias. Diastasis recti is usually seen in the absence of a previous midline incision. Flank pseudohernias may require imaging such as computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen to demonstrate that the musculoaponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall are intact.

Neoplastic masses, such as desmoid tumors or other soft tissue tumors, such as lipomas and sarcomas, can potentially be mistaken for hernias, especially an incarcerated hernia, because they do not change with straining or coughing and obviously cannot be reduced. Infections causing fluid collections, such as an abscess or seroma formation after prior herniorrhaphy or abdominoplasty, can cause bulging that could be mistaken for a hernia and can occur or become evident weeks to years after the herniorrhaphy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The most common symptom is discomfort or pain directly over the site of the hernia, especially when standing or otherwise increasing intraabdominal pressure; referred pain like a radiculopathy is rare. Patients will complain of a bulge, loss of abdominal wall support (often with back pain), or a feeling that they are “falling out” if the hernia is large. Patients often find the hernia cosmetically unacceptable. Localized borborygmi may also be evident to the patient, as may visible peristalsis.

Hernias may cause varying degrees of intestinal obstruction— acute, chronic, or intermittent. Predisposing factors include chronic or acute incarceration and a small hernia neck, especially with a relatively large protrusion of intraabdominal content relative to the neck size. Intermittent, partial small intestinal obstruction may manifest as cramping, abdominal pain, or emesis, and patients may have learned to massage the hernias to provide relief. Acute or chronically incarcerated hernias may cause more severe obstructive symptoms, including acute, complete small intestinal obstruction or chronic, partial obstruction. Although much less common, large bowel obstruction may occur and manifest as constipation or acutely as obstipation.

Examination of the patient with an incisional hernia should be performed in both the supine and erect positions. This approach may provide valuable information to the examiner—reducibility, the extent to which the hernia protrudes, and to what extent the abdominal domain has been lost. The two most prevalent findings on physical exam are the presence of a bulge over or lateral to the prior incision and a palpable fascial defect. If the hernia reduces spontaneously in the supine position, the examination can be aided by having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver, standing, or both. Usually, the hernia can be elicited merely by having the patient lift his or her head off the examination table. Subtle and smaller hernias can be difficult to detect and may manifest during examination as a gentle,

slowly developing bulge under the examiner’s fingers; in the obese patient, small hernias may be difficult or impossible to appreciate.

The edges of the hernia defect should be determined circumferentially by palpation with the patient supine and relaxed. The dimensions are important in determining whether musculoaponeurotic apposition will be possible at the time of repair. Beware the possibility of a “Swiss cheese” hernia, that is, small multiple defects along the fascial incision, especially when the fascia had been closed previously with interrupted sutures; smaller defects may not be palpable. As noted previously, an incarcerated hernia must raise other possibilities in the differential diagnosis, such as seromas, abscesses, and both benign and malignant abdominal wall masses.

The examiner should palpate carefully over any prior port site after a laparoscopic procedure for a subtle defect or “mass.”

Intramural hernias, where at least the most superficial musculoaponeurotic layer remains intact, can occur after lateral celiotomies where the abdominal wall has several layers. Spigelian hernias can present as intramural hernias. Intramural hernias are rare and can be difficult to diagnose and often impossible to feel. A Valsalva maneuver during CT or even ultrasonography may be diagnostic when physical exam and even a passive CT cannot demonstrate the hernia.

For very large hernias that remain evident with the patient supine, an estimation should be made as to the extent to which the herniated contents have lost domain; that is, there is no longer adequate room within the abdominal cavity to accommodate the extruded contents after attempted reduction back into the coelomic cavity. CT of the abdomen is also particularly helpful in this regard. Loss of domain can preclude fascial apposition, even with concomitant component separation or relaxing incisions. Substantial loss of domain will cause undue tension in repairs, respiratory compromise, and an increased risk of recurrence after repair. Severe loss of domain precludes repair.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The best imaging technique for incisional hernia is CT. CT provides excellent and actionable information regarding the size and configuration of the hernia defect, can provide a visual estimate of loss of domain and other potential pathologies in the differential diagnosis, and will aid in planning of the operation. In large, complex hernias, the information can assist with decisions regarding the procedure of choice as well as the potential for adjunctive measures such as tissue (skin surface area) expanders. For flank hernias, CT can rule out a pseudohernia and is important to define the status of the oblique muscles cranial and caudal to the defect, as well as the paraspinal muscles, which will need to serve as fixation points for the hernia prosthesis.

Routinely obtaining a CT to define the hernia defect, position, and size is controversial. For straightforward incisional hernias easily felt and defined at examination, CT has little benefit. For large, complex, or recurrent hernias, especially after prior repairs, CT can provide a wealth of information to define size and conformation, position of any prior prosthetics, issues of abdominal domain, unappreciated additional defects, and the status of the abdominal musculature such as loss or atrophy of specific muscle layers—critical information when planning a concomitant component separation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is acceptable but provides no more information than CT while being more expensive, time consuming, and difficult for the patient (and for many physicians as MRI is more difficult to interpret). Ultrasonography can be helpful, especially with the diagnosis of intramural hernias but is not generally useful and provides far less information than CT.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Timing of Operation

Although most incisional herniorrhaphies are elective operations, acutely incarcerated hernias are surgical emergencies, particularly when strangulation is suspected. Signs of strangulation may include: nausea and vomiting; peritonitis; acutely inflamed, indurated skin overlying the hernia; new onset of constant severe hernia pain; and the signs and symptoms of local or systemic sepsis.

As a general rule, elective incisional herniorrhaphy should be delayed until optimum conditions for repair have been achieved; this approach will decrease recurrence rate. Timing of repair, however, is relative to the patient and the hernia; for example, a small-necked hernia considered at high risk for incarceration would prompt an earlier repair especially if symptomatic, whereas a patient with multiple, potentially remediable risk factors for recurrence, such as obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, tobacco use, malnutrition, constipation, or chronic cough, would argue for a delayed approach until these issues are addressed. More immediate concerns that should delay repair for the shorter term would include, open wounds on the abdominal wall, cellulitis, panniculitis, or cutaneous candidiasis; distant infections such as pneumonia or urinary tract infection; and uncontrolled, potentially reversible medical conditions such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A nonmature (“nonpinchable”) split thickness skin graft overlying the hernia is a relative indication for delay, as is waiting to receive recoverable operative notes from prior abdominal operations prior to operation.

Open versus Laparoscopic Repairs

The topic of open versus laparoscopic repairs is controversial. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and the data regarding hernia recurrence, pain, and postoperative complications are roughly comparable. There are factors that may predispose toward one or the other approach in a particular patient; a surgeon routinely performing hernia repairs should be conversant with both. A recent Cochrane review examined 10 randomized controlled trials with a total of 880 patients comparing laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repairs. They did not note any difference in recurrence rates or postoperative pain intensity. Laparoscopic repairs carried a greater risk of enterotomy and incurred greater inhospital costs, but they were associated with a decreased risk of wound and mesh infection and shortened hospital stay.

Factors favoring open repair: Theoretically, returning the abdominal musculature to its normal position of continuity could be expected to restore optimal anatomic and physiologic functionality of the mechanics of the abdominal wall, although

this remains unproven. Apposition of the musculature in its anatomic position is more easily accomplished in an open procedure. Although fascial apposition can be accomplished laparoscopically, as can a limited component separation, these are performed more efficiently and completely in an open procedure, and more complex component separations including the rectus sheath rollover technique can be accomplished. The fascial apposition performed laparoscopically usually leaves a cosmetically undesirable ridge of skin and subcutaneous fat above the repair. Dense adhesions, especially those resulting from an open wound and subsequent split thickness skin grafting, make a laparoscopic repair difficult or impossible.

Preoperative Planning

Several factors can affect the recurrence rate of incisional hernia repair. With a recurrence rate of 10% to 30% or greater, attention to the factors that adversely affect recurrence rate in the preoperative phase is warranted.

Weight loss: If patients are substantially overweight, certainly if they meet medical criteria for severe obesity, an attempt at weight loss prior to repair is warranted. If the patients are not able to lose weight successfully after a reasonable period of time, however, it may be reasonable to proceed with repair.

Tobacco use: Experts in abdominal wall reconstruction are in general intolerant of tobacco use prior to hernia repair, certainly within 6 weeks prior to the repair and especially if a components separation is planned. The adverse effects of tobacco use on wound healing are well documented in the medical literature. It is worthwhile noting that nicotine substitutes such as gum would be expected to cause the same vasoconstriction and tissue ischemia as inhaled and oral tobacco products.

Abdominal wall strain: Voluntary and involuntary abdominal wall contractions can place an immense strain on a fresh abdominal wall reconstruction—coughing, constipation, emesis, and straining to urinate all place stresses on the abdominal wall that could have an adverse effect on herniorrhaphy. Any remediable causes of these problems should be addressed prior to operation. Routine screening: It is worthwhile to make certain that patients are up-to-date with routine medical maintenance and screening such as colonoscopy so that other necessary intraabdominal conditions can be treated concomitantly, beforehand, or sequentially with the herniorrhaphy as appropriate.

Routine health maintenance: A general preoperative clearance is useful to make certain the patient is medically optimized for operation. Common diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, COPD, and coronary artery disease, should be evaluated and optimized prior to operation to minimize perioperative risk.

Incisional hernia repair is usually a clean case. Because enterotomies can occur and repairs usually entail the placement of either a synthetic or biologic prosthesis, perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are indicated. Bowel preparation is not indicated. A preoperative shower with chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens®) is prescribed at the preference of the surgeon. Adhesive drapes, such as Ioban™ (3M Corp, Minneapolis, MN) and Steri-Drape™ (3M Corp), are used frequently for the theoretic purpose of “isolating skin bacteria” from the wound and any prosthesis used, but strong evidentiary studies to support their use are lacking.

Many hernia cases will require advance notice to ensure that necessary materials and equipment are available.

Planned fixation of the prosthesis to the pubis or anterior iliac spine may require the use of a bone drill or bone anchors.

Specialized, procedure-specific equipment such as a Reverdin needle

Biologic prosthetics (fetal bovine, porcine, or human dermis and others) are expensive and may be stocked in limited supply. Be certain that the prosthesis required in size, thickness, and type is in stock and available the day of operation, as well as alternatives should the originally planned material not be usable as planned.

Positioning

Most incisional hernias can be repaired with the patient supine; the drapes should extend at least 10 to 15 cm above and below the extent of the previous incision. There may be unappreciated defects discovered at the time of operation along the entire extent of the previous incision.

For flank hernias, adequate exposure is paramount. Depending on the incision, a vertically placed bump under the spine providing lateral position may give sufficient access, whereas for more lateral incisional hernias, a complete lateral position may be necessary. See the following “Techniques” section.

Varieties of Repair

The optimal repair of an open incisional hernia is a controversial topic. We will present our choices for what we consider the acceptable and optimal repairs, as well as general considerations that are valid regardless of the other technical details. For most purposes, we consider fascial apposition with a prosthesis underlay in the retrorectus or preperitoneal position to be the best repair for most open incisional hernias.

Choice of Mesh

In general, the synthetic (alloplastic) meshes are preferable when there is no contamination precluding their use, whereas biologic prostheses are preferable when microbial contamination is present. There are innumerable choices for both synthetic and biologic prostheses and little to support the superiority of one particular type over another within their respective classes. It is useful to categorize broadly the various products by functional use. The most important distinction is synthetic versus biologic. The biologic prosthetics are in general more resistant to bacterial colonization and infection and may be chosen in a contaminated field, but they may remodel and weaken over time, especially when used in a bridging fashion. The synthetics are stronger than the biologic meshes and do not remodel, although a varied extent of shrinkage does occur, depending on the prosthetic material. The synthetics may be further subdivided into barrier and nonbarrier meshes. Barrier meshes are designed to allow them to be apposed to the abdominal viscera are in theory minimize adhesions to the side facing intracorporeally. Nonbarrier synthetics should only be used in a protected space, such as the preperitoneal or retrorectus spaces.

Procedure Categorization

Open

Fascial apposition alone

Fascial apposition with prosthesis underlay

Protected space mesh placement (preperitoneal and retrorectus)

Intraperitoneal mesh placement

Fascial apposition with prosthesis overlay

Components separation

Laparoscopic

Prosthesis underlay

Suture fixation with tacks

Tack fixation alone

Fascial apposition

Components separation

TECHNIQUES

WIDE ONLAY TECHNIQUE OF INCISIONAL HERNIORRHAPHY

The concept behind this wide onlay repair is that the procedure can remain fully extraperitoneal, and the meshed prosthesis provides a large surface area for transgrowth through the mesh and thus a wide tissue fixation.

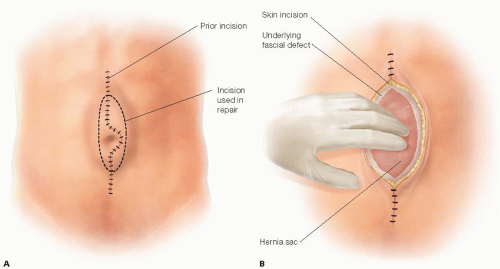

Placement of Incision

The entire prior skin incision is excised along with any underlying fibrosis back to healthy epidermis and subcutaneous fat in attempt to minimize infection (FIG 1A).

Dissection proceeds directly down to the hernia sac, being careful not to enter the sac. If the incision is longer than the hernia defect, only the skin and subcutaneous tissues that are chronically scarred with concerns for healing need be excised. This type of repair can be accomplished totally extraperitoneally. The lateral aspect of the hernia sac is mobilized medially back to the fascial defect. This maneuver may be accomplished purely by blunt dissection, but if the interface of sac and subcutaneous tissue is scarred, sharp dissection may be required (FIG 1B).

Creation of Space for Prosthesis

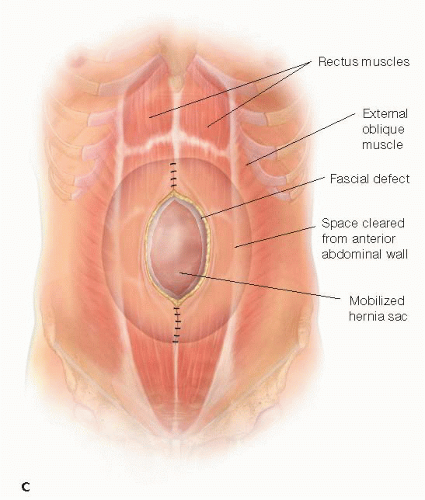

The skin and subcutaneous tissue flaps are mobilized for at least 5 to 7 cm lateral to the edge of the hernia defect. This plane is created just anterior to the abdominal wall fascia (anterior rectus fascia and possibly out to the external oblique fascia or aponeurosis more laterally) to allow a wide, lateral overlap of the prosthesis. A 5- to 7-cm skin and subcutaneous flap is mobilized off the midline fascia past the cranial and caudal extents of the hernia defect (FIG 1C).

Reapproximation of Fascia Edges

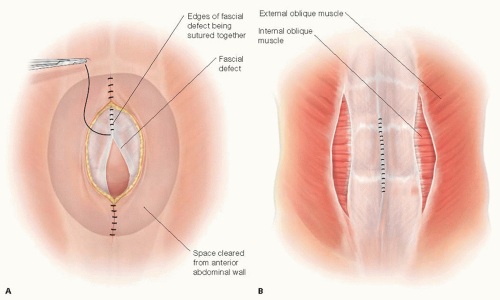

A decision needs to be made whether and how the fascial edges of the defect can be reapproximated (FIG 2A) or only bridged or “patched” by the prosthesis (FIG 2B) (see Part 2, Chapter 5). If the fascial edges are to be sutured together, some dissection under the fascial edges may be necessary to place the fascial sutures safely. Most surgeons believe that reapproximation of the fascial edges reinforced by a prosthesis provides a superior outcome compared to a bridge or patch of a persistent fascial defect. If the defect is wide and would require a more complicated abdominal wall reconstruction, the advantages and disadvantages should be considered. In this situation, the skin flaps can be dissected further laterally beyond the lateral border of the rectus muscle; then the external oblique fascia and muscle can be transected being careful not to disrupt the internal oblique muscle/fascia—a form of anterior components separation—this maneuver allows the rectus muscle to be “medialized” and the medial edges of the fascia to be sewn together (FIG 2C) (see Part 2, Chapter 5, for more in-depth description). This maneuver allows 4 to 6 cm of medialization of the rectus muscles on both sides. Another option to “approximate” the fascial edges of the defect is a rectus rollover technique (FIG 2C). With this technique, the anterior rectus fascia is incised just medial to its lateral border, mobilized off the underlying rectus muscle, and “rolled” medially. These edges of the rolled anterior rectus fascia can be sutured together in the midline. Note that the rectus muscles are not medialized with this technique.

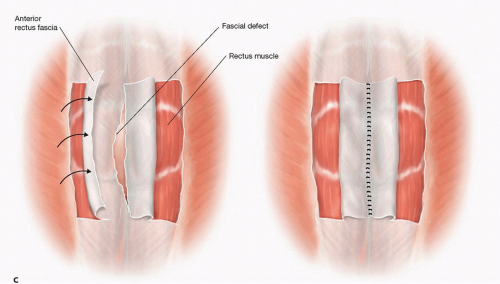

Placement of Prosthetic Mesh

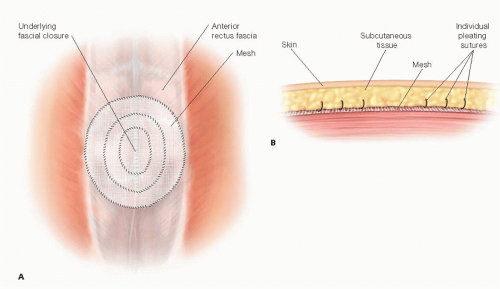

A large sheet of prosthetic mesh is then sized to cover the anterior abdominal wall hernia defect and to extend a further 5 to 7 cm from the hernia defect (so-called “wide onlay”) on all sides of the defect. The lateral edges of the prosthesis are sewn to the anterior abdominal wall fascia circumferentially with #0 or no. 1 suture material (e.g., 0 or no. 1 polydioxanone) (FIG 3). The use of absorbable versus permanent sutures is controversial. Proponents of permanent sutures believe that permanent sutures minimize the possibility of late migration or dislodgement of the prosthesis, whereas those surgeons favoring the longer lasting absorbable suture (such as polydioxanone) believe that permanent sutures can lead to suture granulomas and ultimately contamination and infection of the prosthesis. Although there is no good evidence supporting either argument, we prefer the absorbable suture provided there will be a large surface area for mesh transgrowth.

In progressively smaller concentric circles, one or two additional suture fixation of the prosthesis to the underlying anterior abdominal wall can also be placed (FIG 3A). If the repair is a bridge repair, these concentric circles should not extend medial to the edges of the fascial defect because the underlying hernia sac and viscera can be injured. A porous synthetic prosthetic and not a solid prosthetic (ePTFE) is used to achieve the goal to provide a

wide surface area for transgrowth through the mesh for tissue fixation.

If an anterior components separation is performed, the prosthesis extends laterally to the lateral transected edge of the external oblique aponeurosis (a very wide onlay repair) or just 5 to 7 cm lateral to the medial edge of the hernia defect which is usually to the lateral edge of the rectus muscle.

If a rectus rollover is performed, the prosthesis should extend 5 cm lateral to the site of incision in the anterior rectus fascia to provide solid points of fascial fixation of the prosthesis.

For situations where there is bacterial contamination (clean-contaminated cases) or active infection, albeit treated, a synthetic mesh is contraindicated, and a bioprosthesis would be a better choice.

Wound Closure

Most surgeons place one or two closed suction drains in the large subcutaneous space to prevent a seroma. When the drains should be removed is controversial; for a bioprosthesis, drains are mandatory to prevent a seroma.

Prior to closing the skin, a pleating technique may be used, whereby the posterior adipose surface of the skin/subcutaneous flaps can be sewn to the anterior surface of the prosthesis in attempt to minimize the “dead space” and the possibility of seroma (FIG 3B).

RECTRORECTUS SUBLAY REPAIR: MODIFIED RIVES-STOPPA REPAIR

Many believe that this repair has the best results of all current incisional herniorrhaphies. Whether it is better than a wide, intraperitoneal sublay (IPOM) can be debated, but there are no studies comparing the two repairs. This modified Rives-Stoppa repair is based on the principle of wide surface area of a meshed synthetic prosthesis placed in a very vascular field—the retrorectus space (to allow a stable, reliable anterior and posterior transgrowth for mesh fixation). Importantly, the prosthesis is neither in the less vascular subcutaneous space where the risk of infection and seroma is greater nor is the prosthesis direct in contact with the intraperitoneal viscera. Moreover, in most patients, the repair can be accomplished extraperitoneally.

Placement of Incision

As with other repairs, the incision should be made directly over the hernia defect with resection of the skin incision and the underlying, poorly vascularized scar tissue. The skin incision preferably should not extend all the way up to the xiphoid or all the way down to the pubis but rather stay 5 to 8 cm away from xiphoid and pubis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree