Incisional Hernia: Laparoscopic Approaches

Todd Heniford

Kristopher Williams

DEFINITION

Incisional hernia is defined as any abdominal wall defect occurring at the site of previous operation or scar. Laparoscopic incisional hernia repair uses prosthetic mesh reinforcement, much like as originally described by Stoppa,1 applied through minimally invasive operative techniques with reliable success.2

Incidence of incisional hernia following laparotomy exceeds 20% with over 2 million laparotomies performed in the United States annually, a factor contributing to the estimated 348,000 ventral hernia repairs in 2006.3,4 Recurrence rates for primary suture hernia repair have been reported to be as high as 54%,5 which have been reduced by more than half with the use of mesh reinforcement.6,7

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Diastasis recti

Seroma

Hematoma

Abdominal wall abscess

Hypertrophic scar

Desmoid

Abdominal scar endometrioma (at sites of previous cesarean or hysterectomy incisions)

Soft tissue sarcoma

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A detailed general health history should be obtained including past medical history, current medications, allergies, social habits (alcohol, illicit drug use, smoking history) as well as previous adjuvant treatments, which may impact any attempt at operative repair (e.g., previous pelvic or abdominal radiation). Consideration of other common abdominal pathology, such as symptomatic cholelithiasis or colon cancer, may need evaluation prior to hernia repair and results should be documented.

A detailed history regarding obstructive symptomology (nausea, vomiting, passage of flatus, bowel frequency, abdominal pain) the patient may have experienced in the recent or distant past should be recorded. For all patients undergoing evaluation of incisional hernia, medical records should be obtained and reviewed, emphasizing surgical history and operative reports from previous pertinent surgeries and hernia repairs. Attention should be directed toward specifics of previous abdominal operations, especially hernia repairs: anatomic location of initial hernia defect, previous attempts at hernia repair, presence and type of previously placed mesh, location of any previously placed mesh (intraperitoneal, preperitoneal, retrorectus, fascial onlay, etc.), method of mesh fixation, and previous operative complications. Also, the extent of previous skin and subcutaneous dissection and the presence and extent of a components separation can be very helpful.

The presence of comorbidities known to be associated with increased risk of postoperative wound complications or recurrence (current or smoking history, obesity, diabetes, immunocompromised status, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], current or chronic infections such as urinary or pulmonary infection, history of previous mesh or other methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] infections), as well as any history of previous or current wound infections and any current abdominal wall wound issues should be noted.

A complete physical exam should be performed paying particular attention to the existence and location of abdominal scarring, nonhealing wounds, erythema that may indicate deeper pathology, identification of any abdominal wall defects (either incisional or primary), presence and nature of hernia contents within defects, reducibility of hernia contents, and tenderness to palpation of noted defects. Fascial defect size should be estimated to aid in preoperative planning.

Other physical findings or review of symptoms points may alert a surgeon to medical issues that require workup prior to surgery, such as heart failure, COPD, vascular disease, liver or kidney disease.

A thorough examination should be performed looking for the existence of other potential hernia sites (umbilical, inguinal, femoral, parastomal, etc.), which may be addressed at the time of surgery. By neglecting other potential hernias, the opportunity to repair them at the same time as the primary hernia may be lost.

The presence of a gastrointestinal stoma, active wound infection, or chronic draining sinus tracts should also be taken into account, as these situations influence operative planning, risk counseling, and may influence an open versus a laparoscopic repair. A laparoscopic repair with synthetic mesh placement is not appropriate for an actively infected field.

The presence of peritoneal signs (abdominal rigidity, guarding, rebound tenderness) should alert the surgeon to the likelihood of intraabdominal issues and may mandate an emergent laparotomy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Although physical exam is the gold standard of diagnosis, obese body habitus, abdominal scarring, and the presence of previously placed mesh may preclude physical diagnosis of an incisional hernia. For these reasons, computed tomography (CT) is a valuable tool for diagnosis and operative planning in cases of a suspected incisional hernia (FIG 1).

Advantages of CT imaging for the evaluation of incisional hernias are multifactorial: accurate diagnosis in cases of obscure or small defects; proper identification of hernia contents (small bowel, colon, solid organs, omentum, etc.); definition of defect size; location of previously placed mesh; distinction from other or concomitant potential diagnoses (seroma, abscess, hematoma, etc.); identification of bowel incarceration; obstruction or possible ischemia, necrosis, or perforation; and planning of where to enter the abdomen safely.

When feasible, it is helpful for the operating surgeon to review the actual CT images, as the information discussed earlier may not be included in a radiologist’s reading of the films. It is also helpful to have CT images available to be viewed intraoperatively as they can serve as a reference during the operative procedure.

Colon cancer screening with colonoscopy or other appropriate means is often considered for those patients who have reached appropriate age for screening, have a significant family history, or other colonic symptoms prior to hernia repair.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

For elective procedures, in the weeks leading up to repair, attempts should be made at optimization of preoperative patient factors associated with increased risk of postoperative wound complications: smoking cessation, evaluation and maximization of nutrition status, tight blood glucose control, weight loss in the obese, or elimination of open wounds through local wound care.8

Appropriate intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered prior to incision and repeated as needed to provide adequate prophylactic coverage depending on length of procedure and drug half-life.9

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis should be provided, such as lower extremity serial compression devices or subcutaneous prophylactic dose heparin prior to induction of anesthesia, assuming no contraindications.9

Following induction of anesthesia, the abdominal wall is reexamined to confirm the borders of the defect in question and to identify the presence or location of previous mesh, signs of infection, or other issues.

Intraoperative urinary and gastric decompression are recommended.

Iodophor-impregnated adhesive skin drape may be used to minimize mesh contact with skin surfaces and therefore reduce the risk of mesh infection, although this has not been proven in randomized clinical trials.

Positioning

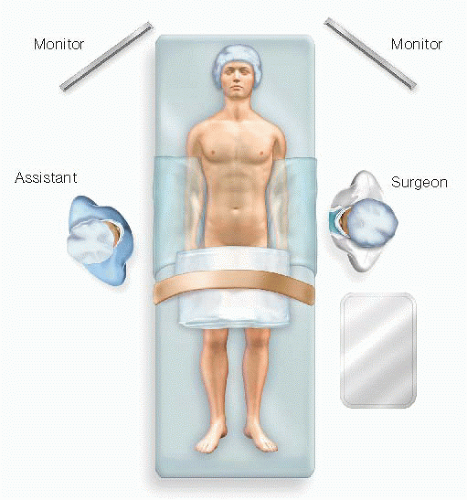

The patient should be positioned supine with arms adducted and tucked at sides of body with adequate padding of pressure points to avoid neurologic pressure injury. This allows movement of the surgeon and the assistant on each side of the table during the operation (FIG 2).

Semilateral or lateral decubitus position may be favored for repair of flank or lumbar hernias.

The patient should be secured to the operating table to allow steep positioning or rolling of the table as required during the procedure.

Laparoscopic monitors should be positioned over the working space to allow direct vision by both the primary surgeon and assistant.

TECHNIQUES

INITIAL ACCESS

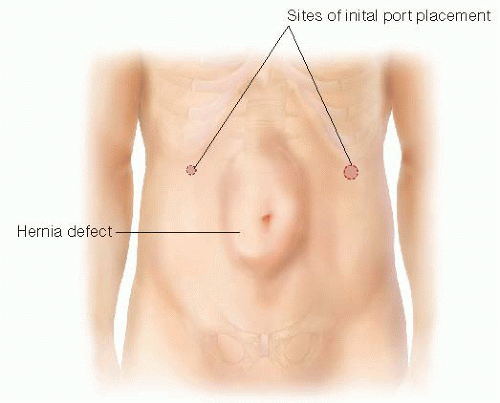

A safe window of intraperitoneal access is usually available in areas distant from site(s) of previous surgery, although an open, “cut-down” technique can be performed near or within a hernia if the surgeon prefers.

Often, safe entry is found just inferior to the tip of the 11th rib, between midclavicular and anterior axillary lines (FIG 3).

Open cut-down technique is most often performed with identification of individual abdominal wall layers as each is entered, but some surgeons use a port that allows visualization of the abdominal wall layers with the laparoscope as the trocar is slowly advanced into the abdomen.

Pneumoperitoneum is established at 12 to 15 mmHg.

PLACEMENT OF WORKING PORTS

Using an angled (30- or 45-degree) scope, a brief general inspection of the abdominal cavity checking for organ injury, which may have occurred during initial access, is performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree