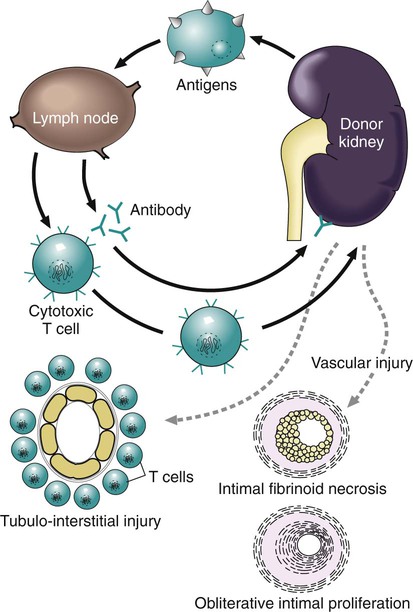

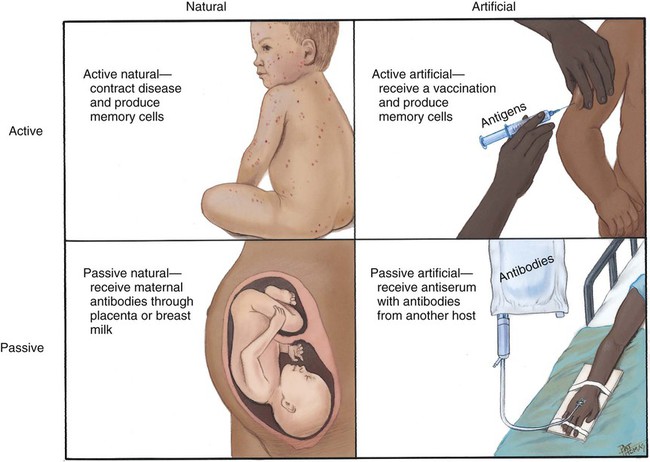

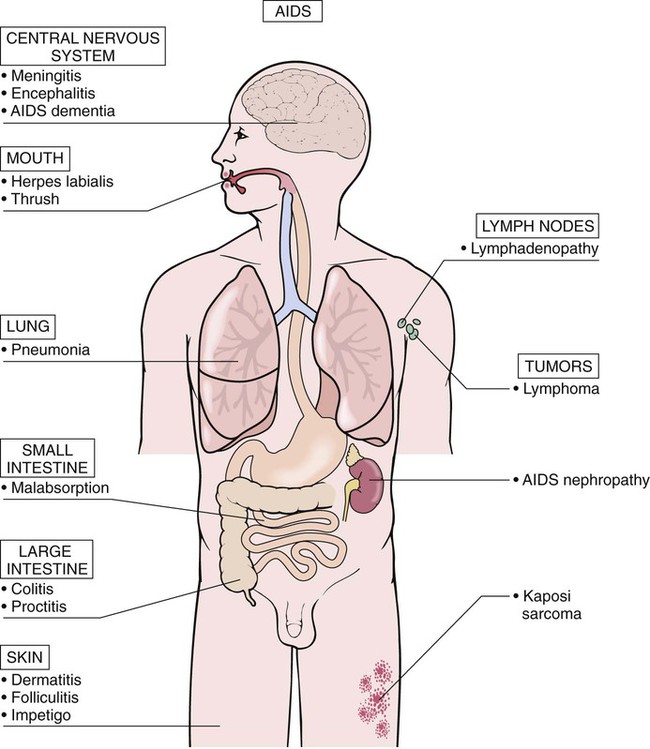

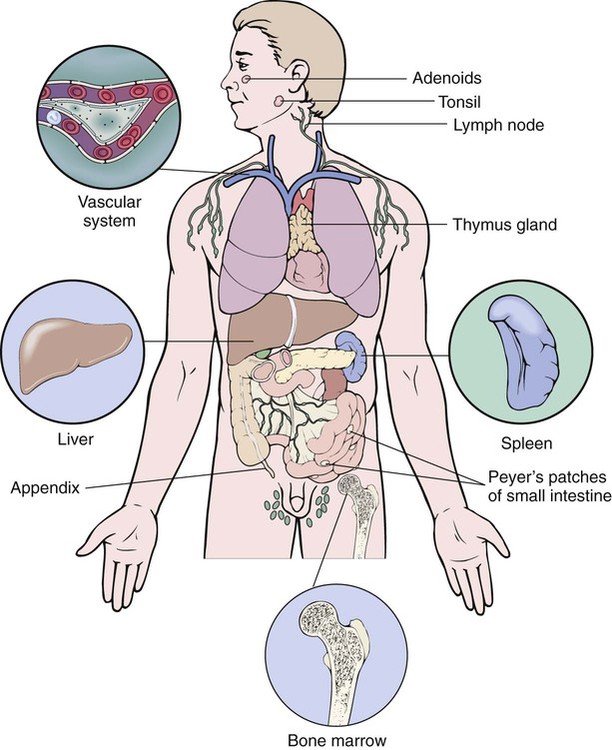

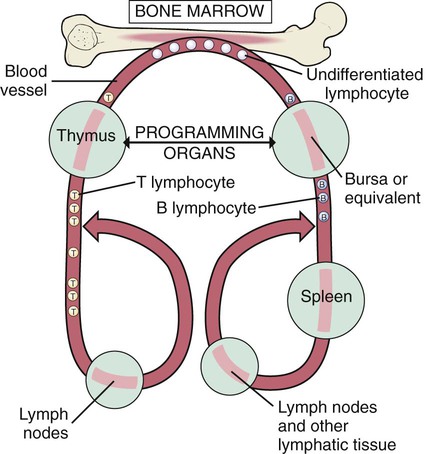

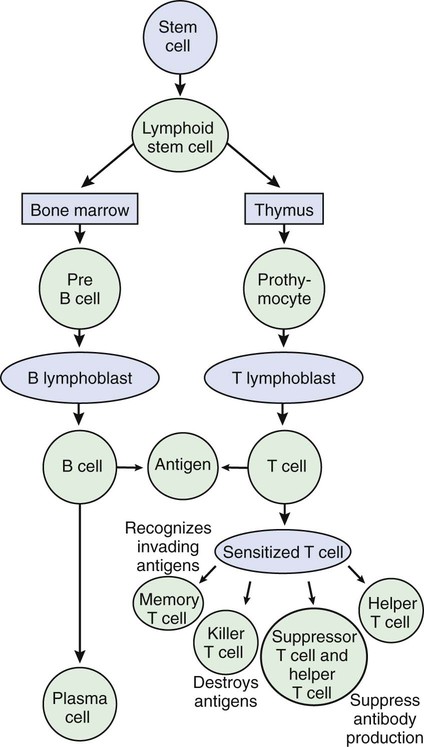

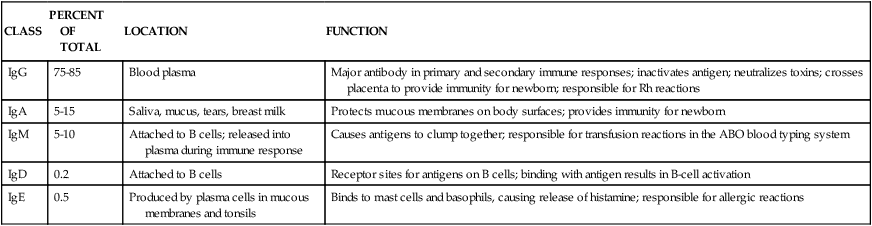

After studying Chapter 3, you should be able to: 1. Name the functional components of the immune system. 2. Characterize the three major functions of the immune system. 3. List examples of inappropriate responses of the immune system. 4. Explain the difference between active and passive immunity. 5. Trace the formation of T cells and B cells from stem cells. 6. Explain how T cells and B cells specifically protect the body against disease. 7. List the five immunoglobulins and explain complement fixation. 8. Explain the ways that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is transmitted. 9. List the guidelines for universal precautions and infection control. 10. Describe the primary absent or inadequate response of the immune system in the following diseases: • Common variable immunodeficiency • Selective immunoglobulin A deficiency • Severe combined immunodeficiency disease 11. Explain the destructive mechanisms in autoimmune diseases. 12. Describe the symptoms and signs of pernicious anemia. Name the primary treatment. 13. Recall the systemic features of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Recall the diagnostic criteria. 14. Detail the pathology of rheumatoid arthritis. 15. Specify the primary objectives of the treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. 16. Compare the pathology of multiple sclerosis with that of myasthenia gravis. 17. List the distinguishing diagnostic features of ankylosing spondylitis. The immune response assists the body in maintaining its functional integrity, and it battles infection by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. The immune system involves lymphoid tissues classified as primary (thymus and bone marrow) or secondary (tonsils, adenoids, spleen, Peyer’s patches, appendix, etc.) (Figure 3-1). • Hyperactive responses (e.g., allergies), in which the immune response is excessive • Immunodeficiency disorders (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), in which the immune response is inadequate • Autoimmune disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), in which the immune response is misdirected against one’s own tissues • Attacks on beneficial foreign tissue (e.g., reaction to blood transfusions or transplanted organ rejection). (See Enrichment box on Transplant Rejection.) • Natural killer (NK) cells that kill virus-infected cells and tumor cells by secreting certain toxins • Macrophages that phagocytose bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances • Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs or simply neutrophils) that also phagocytose bacteria The development of the components required for immunity begins early in fetal life when the fetal liver produces stem cells, which in turn produce all cells of the hematopoietic system. Bone marrow assumes this role after birth (Figure 3-3). Some of the stem cells migrate to the thymus gland, where they become T cells (T lymphocytes), which multiply and develop the capacity to combine with specific foreign antigens derived from viruses, fungi, tumors, or transplanted tissue (Figure 3-4). Those T cells coded to recognize self-antigens are destroyed. The remaining T cells are coded to seek out foreign invaders. The body produces several types of T cells; each has a different function: • Cytotoxic T cells (killer T cells) directly destroy virus-infected cells, tumor cells, and allograft cells by releasing certain toxins or by inducing apoptosis. These cells also may be referred to as CD8 cells because they carry the CD8 glycoprotein on their surface. • Helper T cells stimulate the B cells to differentiate into plasma cells and to produce more antibodies. They also activate cytotoxic T cells and macrophages. Helper T cells carry the CD4 glycoprotein on their surface. • Suppressor T cells inhibit both B- and T-cell activities and moderate the immune response. • Memory T cells remain dormant until they are reactivated by the original antigen, allowing a rapid and more potent response years after the original exposure. The remaining stem cells develop into B cells (B lymphocytes) to produce the antibody-mediated (humoral) immunity that protects the body against bacterial and viral infections and reinfections (see Figure 3-4). Once activated by exposure to an antigen, B cells are stimulated to proliferate and form a clone of cells that respond to that specific antigen. Some B cells become antibody-secreting plasma cells, whereas others become memory B cells, ready for a quick response if the target antigen presents itself again. The plasma cells are responsible for producing antibodies that attach to invading foreign antigens, thus marking the antigens for destruction by other cells of the immune system. B cells are coated with immunoglobulins, giving them the ability to recognize foreign protein and stimulate an antigen-antibody reaction. The five classes of immunoglobulins or antibodies are IgM, IgG, IgA, IgD, and IgE (Table 3-1). These immunoglobulins are usually all present during an antigenic response, although in varying amounts, depending on the stimulant and the health of the patient. Actions of the antigen-antibody complex include the following: TABLE 3–1 From Applegate EJ: The anatomy and physiology learning system, ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Saunders. • Inactivation of the pathogen or its toxin through direct binding. • Stimulation of phagocytosis through complement fixation, the process by which an antibody targets an infected cell for destruction by binding to the cell surface. (Phagocytic cells recognize the antibody marker and engulf the infected cell.) The human body is protected by two types of acquired specific immunity: active immunity and passive immunity. Active immunity results when a person has had previous exposure to a disease or pathogen, or when a person receives immunizations against a disease to stimulate the production of a specific antibody. Active immunity affords the person acquired permanent protection. Passive immunity bypasses the body’s immune response to afford the benefit of immediate antibody availability. A person gains passive immunity by being given immune substances created outside that person’s body for temporary immunity, such as antibodies received through the placenta, when breast milk is fed to a child, or when immune globulin, an antibody-containing preparation made from the plasma of healthy donors, is given to help a person combat disease (Figure 3-5). Initially it is not possible to tell whether people are infected with HIV by simply observing them. They may remain healthy for years during the latent period and may therefore unknowingly transmit the virus to other people. Within 1 to 4 weeks after exposure, the patient may experience a flulike illness with sore throat, fever, and body aches that often lasts about 2 weeks. Lymphadenopathy, weight loss, fatigue, diarrhea, and night sweats are common as the clinical course progresses. The body’s number of T cells becomes lower and allows for frequent infections, especially opportunistic infections, pneumonia, fever, and malignancies (see the Enrichment box for Malignancies and Common Opportunistic Infections and Conditions in Patients with AIDS). Often, in the later stages, encephalopathy and malignancy lead to dementia and death (Figure 3-9). Health care practitioners who are involved in various forms of patient care with exposure to body fluids and blood should follow the principles of infection control and universal precautions (see the Alert box for Infection Control and Universal Precautions). All body fluids and blood from any patient should be handled with extreme care, as if the patient were known to be infected with HIV. Children with DiGeorge’s anomaly often have a set of structural abnormalities. These include abnormally wide-set, downward slanting eyes; low-set ears with notched pinnas; a small mouth (Figure 3-10); abnormalities of the palate; and cardiovascular defects such as tetralogy of Fallot. The thymus and parathyroid glands are absent or underdeveloped. The infant exhibits signs of tetany due to hypocalcemia caused by hypoparathyroidism. Some degree of cognitive impairment often is present. The patient is susceptible to severe viral, fungal, and protozoan infections. The most common of these are pneumonia and thrush in infants.

Immunologic Diseases and Conditions

Orderly Function of the Immune System

CLASS

PERCENT OF TOTAL

LOCATION

FUNCTION

IgG

75-85

Blood plasma

Major antibody in primary and secondary immune responses; inactivates antigen; neutralizes toxins; crosses placenta to provide immunity for newborn; responsible for Rh reactions

IgA

5-15

Saliva, mucus, tears, breast milk

Protects mucous membranes on body surfaces; provides immunity for newborn

IgM

5-10

Attached to B cells; released into plasma during immune response

Causes antigens to clump together; responsible for transfusion reactions in the ABO blood typing system

IgD

0.2

Attached to B cells

Receptor sites for antigens on B cells; binding with antigen results in B-cell activation

IgE

0.5

Produced by plasma cells in mucous membranes and tonsils

Binds to mast cells and basophils, causing release of histamine; responsible for allergic reactions

Immunodeficiency Diseases

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

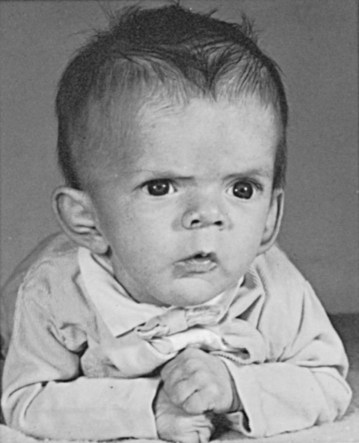

DiGeorge’s Anomaly (Thymic Hypoplasia or Aplasia)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree