BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Modified from Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72.

Epidemiology

- An estimated 66.9 million people, with an overall prevalence rate of 30.4%, have HTN based on 2003–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, a substantial increase from earlier estimates of 50 million from 1988 to 1994.2

- The growing prevalence is directly related to an aging population and a higher rate of obesity.

- HTN is more common in dark-skinned individuals of African descent and those with a family history of HTN. The prevalence is higher in men than in women until the age of 60, after which women are affected in greater numbers.

- HTN is a major risk factor for the development of CVD, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and dementia, with most affected patients dying from ischemic heart disease.

- Reversible risk factors include prehypertension, being overweight or obese, excessive alcohol intake, a high-sodium low-potassium diet, and a sedentary lifestyle.

- Associated conditions include the metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus (DM), kidney disease, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Etiology

- Essential/primary hypertension

- The most common cause of HTN affecting approximately 95% of patients

- Thought to be due to a complex interplay of multiple factors including genetics, increased sympathetic and angiotensin II activity, insulin resistance, salt sensitivity, and environmental influences

- The most common cause of HTN affecting approximately 95% of patients

- Secondary hypertension

- Affects a much smaller minority (about 5%) of patients.

- Secondary to a disease process with a specific identifiable structural, biochemical, or genetic defect resulting in elevated BP.

- Some of the more common examples include renovascular disease, renal parenchymal disease, endocrinopathies, side effect of other drugs, and OSA. These entities are described further in the “Special Considerations” section.

- Affects a much smaller minority (about 5%) of patients.

Screening

- Elevated BP is usually discovered in asymptomatic patients during routine office visits and should, therefore, be checked as part of every health care encounter.

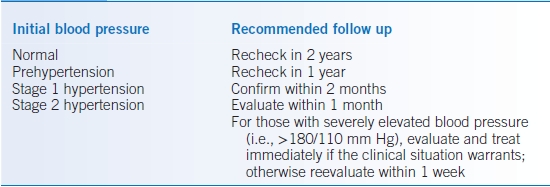

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force strongly recommends HTN screening but the optimal screening interval for HTN is unknown.6 Current recommendations call for checking BP at least every 2 years in those with normal BP (<120/80 mm Hg) and annually for persons with prehypertension. Table 6-2 presents a suggested time frame for follow-up evaluations based on BP measurements.3,7

- If systolic and diastolic categories are different, follow recommendations for the shorter follow-up.

- The schedule may be modified based on reliable information about past BP measurements, other CV risk factors, and target organ damage.

TABLE 6-2 Recommendations for Follow-Up Based on Initial Blood Pressure

Modified from Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72.

DIAGNOSIS

- The diagnosis of HTN is established by documenting SBP of ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP of ≥90 mm Hg, based on the average of two or more readings obtained on each of two or more office visits.

- A patient may be diagnosed on the basis of an elevated SBP alone, even if the DBP is normal (i.e., isolated systolic HTN).

- With extreme elevations of BP (>210/120 mm Hg), the diagnosis can usually be safely made without the need for serial evaluations. In these circumstances, one should focus on the evaluation of end-organ damage and treatment of hypertensive urgency or emergency as indicated (see “Hypertensive Urgencies and Emergencies”).

- After the diagnosis of HTN has been made, there are three major objectives:

- Assess lifestyle or other CV risk factors that may affect prognosis and guide treatment.

- Reveal a cause of secondary HTN (most often not present).

- Assess the presence or absence of target organ damage.

- Assess lifestyle or other CV risk factors that may affect prognosis and guide treatment.

- The history, physical examination, and further diagnostic testing are the primary tools to achieve these objectives.

Clinical Presentation

History

- Determine additional risk factors that increase the risk for CV events: increased age (men >45, women >55), cigarette smoking, obesity (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2), physical inactivity, dyslipidemia, DM, kidney disease, and family history of premature CVD (for men, age <55, for women, age < 65). Modifiable risk factors should be treated.

- Seek evidence of end-organ damage that may be either known or suggested by characteristic symptoms:

- Coronary artery disease (CAD) or prior myocardial infarction (MI) (angina or exertional dyspnea)

- Heart failure (HF) (symptoms of volume overload and/or dyspnea)

- Prior transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke (dementia or focal deficits)

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD, claudication)

- Renal disease

- Coronary artery disease (CAD) or prior myocardial infarction (MI) (angina or exertional dyspnea)

- Secondary HTN should be considered when BP becomes severely elevated acutely in a previously normotensive individual, at extremes of age (<20 or >50), or if refractory to treatment with multiple medications. Other symptoms that may be helpful include muscle weakness, palpitations, diaphoresis, skin thinning, flank pain, snoring, or daytime somnolence. See the “Secondary Hypertension” section.

- Conduct a thorough evaluation of the patient’s medications, as many agents have side effects of elevated BP. Common examples include oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and tricyclic antidepressants.

- Oral contraceptives induce sodium retention and potentiate the action of catecholamines.

- NSAIDs block the formation of vasodilating, natriuretic prostaglandins and interfere with the effectiveness of many antihypertensives.

- Tricyclic antidepressants inhibit the action of centrally acting agents (e.g., clonidine).

- Oral contraceptives induce sodium retention and potentiate the action of catecholamines.

- Excess alcohol consumption and illicit substances such as cocaine can also raise BP.

Physical Examination

- Blood pressure measurement

- Optimal detection of HTN depends on proper technique.8

- BP should be measured while the patient is in the seated position with the arm supported at the heart level.

- The patient should have avoided caffeine, exercise, and smoking for at least 30 minutes prior to measurement.

- An appropriately sized cuff with the bladder encircling at least 80% of the arm circumference should be used to ensure accuracy.

- The cuff should be inflated rapidly to 20 to 30 mm Hg past the level where the radial pulse is no longer felt and then deflated at a rate of 2 mm Hg/second.

- The stethoscope should be placed lightly over the brachial artery.

- SBP should be noted at the sound of the brachial pulse (Korotkov phase I) and DBP at the disappearance of the pulse (Korotkov phase V).

- Two readings should be taken, ideally separated by at least 2 minutes.

- Elevated values should be confirmed in both arms. If there is a disparity due to a unilateral arterial lesion, the reading from the arm with higher pressure should be used.

- Optimal detection of HTN depends on proper technique.8

- Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

- In some situations, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) can be used to provide further information.3 With ABPM, patients wear automated, lightweight devices that obtain multiple BP measurements at specific intervals throughout a 24- to 48-hour period. It more effectively reflects a patient’s true diurnal variation in BP with lower values during sleep and higher values during wakefulness or activity.

- By ABPM HTN can be defined as an average awake BP >135/85 and average sleep BP >120/75.3

- Studies have suggested that values obtained with ABPM more closely correlate with end-organ complications than do values obtained in the physician’s office.9

- ABPM may be particularly useful in suspected cases of white coat HTN in which the anxiety of the physician encounter may falsely elevate BP while values outside of the office are often normal. The risk of CV events in patients with true white coat HTN is frequently debated but a meta-analysis of eight trials suggested there may be no excess risk over normotensive individuals.10

- Ambulatory monitoring may also reveal masked HTN and nighttime nondippers. Masked HTN indicates patients with normal in-office BP but hypertensive readings during ABPM, and has a prevalence on the order of 10%.11 It is associated with increased CV risk.10,12 Currently, it is not clear whom should be screened for masked HTN. Patients receiving treatment for HTN may also display masked HTN with ABPM. Nocturnal HTN and nondipping (i.e., BP not falling by ≥10% during sleep) are also associated with increased CV events.13,14

- ABPM may also be helpful in guiding treatment decisions in patients with borderline HTN, resistant HTN, or symptoms suggestive of hypotension on treatment.3

- ABPM is often impractical due to cost and poor reimbursement. Home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) with self-measurement of BP may serve as a more practical alternative in patients whose values are consistently <130/80 mm Hg despite an elevated office value.3 It is also recommended as an adjuvant to HTN management.15

- In some situations, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) can be used to provide further information.3 With ABPM, patients wear automated, lightweight devices that obtain multiple BP measurements at specific intervals throughout a 24- to 48-hour period. It more effectively reflects a patient’s true diurnal variation in BP with lower values during sleep and higher values during wakefulness or activity.

- After obtaining accurate BP measurements, the physical examination should be tailored to evaluate the presence and severity of target end-organ damage and any features that may suggest secondary HTN.

- Cardiopulmonary exam: S4 gallop suggesting left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), murmurs, or rales suggesting HF.

- Funduscopic exam: papilledema, arteriolar narrowing, cotton wool spots, and microaneurysms.

- Vascular exam: bruits of major arterial vessels (carotids, femorals, and aorta), asymmetric or diminished distal pulses.

- Neurologic exam: altered mental status or focal findings suggestive of prior stroke.

- Endocrine: elevated BMI, thyroid enlargement, and Cushingoid features (e.g., buffalo hump, striae, and skin thinning).

Diagnostic Testing

- Routine laboratory tests recommended before initiating therapy include serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, blood glucose, hematocrit, lipoprotein profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and urinalysis.

- Measurement of microalbuminuria is recommended in those with DM or renal disease but is otherwise elective and may add to the overall assessment of CV risk.16–18

- An ECG should be obtained in all patients to assess for LVH and/or signs of previous infarct. Although echocardiography is more sensitive at diagnosing LVH, it is not recommended in all patients.

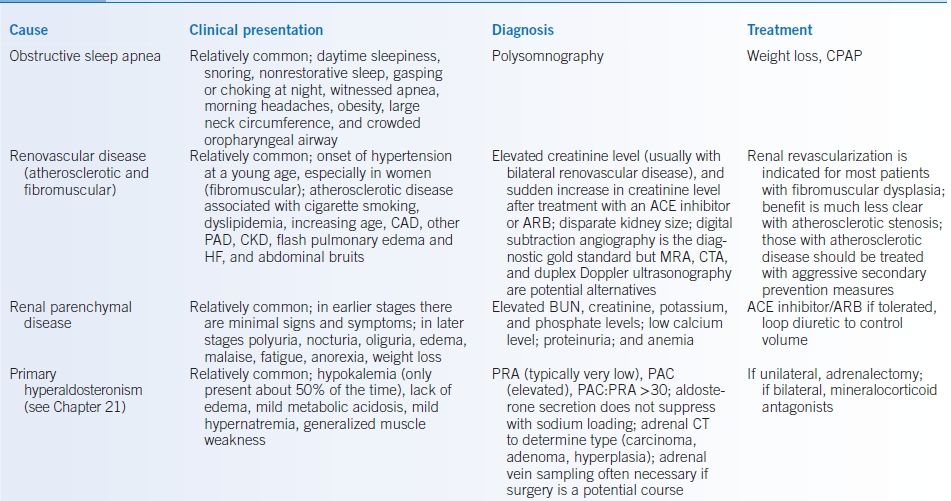

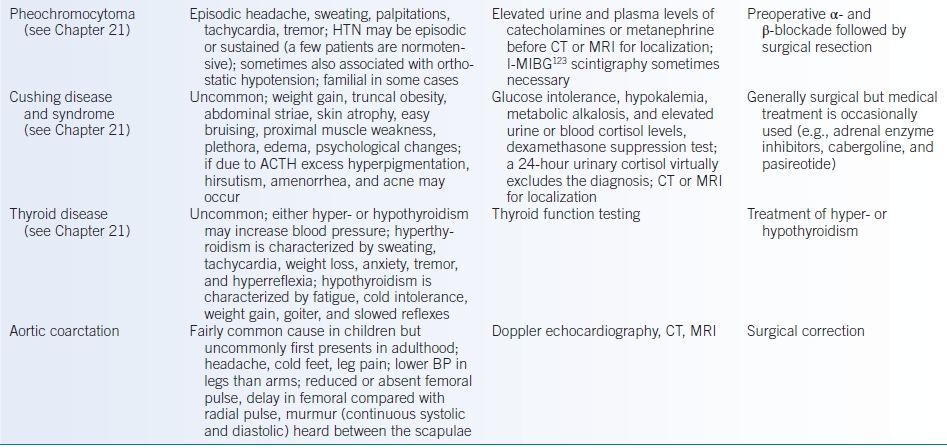

- A more detailed workup can be pursued for features suggestive of a secondary cause of HTN. Some of these are described in Table 6-3.

TABLE 6-3 Causes of Secondary Hypertension

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PRA, plasma renin activity; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; HTN, hypertension; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BP, blood pressure.

TREATMENT

- The goal of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce the morbidity and mortality of CVD attributable to HTN.

- Patient education is an essential component of the treatment plan and promotes better adherence. Physicians should stress the following:

- Lifelong treatment is often required.

- Symptoms are an unreliable gauge of severity (despite many patients’ claims that they can “feel” when their BP is high).

- Prognosis improves with effective management.

- The importance of therapeutic lifestyle changes.

- Adherence to medication therapy is critically important.

- Lifelong treatment is often required.

- All patients with prehypertension or HTN should be counseled regarding therapeutic lifestyle changes.3,19,20 See “Other Nonpharmacologic Therapy”.

- For the general population of patients <60 years old the JNC 8 BP goal is <140/90. This does not differ from the JNC 7 recommendations.3,4

- For the general population of patients ≥60 years old the new JNC 8 goal is <150/90. The prior JNC 7 goal had been <140/90. The JNC believes that the evidence most strongly support the SBP goal of <150 and points out that some data suggest that <140 adds no additional benefit.3,4,21–24

Medications

- Medication treatment is generally considered appropriate/indicated for.4

- Patients <60 years with SBP >140 and/or DBP >90.

- Patients ≥60 years with SBP >150 and/or DBP >90.

- Patients <60 years with SBP >140 and/or DBP >90.

- Starting two drugs in patients with more marked elevation in BP (<60 years >160/100, ≥60 years >170/100) is reasonable.3

- Many factors should be taken into consideration when initiating drug therapy including the following: evidence of improved clinical outcomes, comorbid diseases and other CV risk factors, demographic differences in response, affordability, lifestyle issues, and the likelihood of adherence.

- There is a high interpatient variability in response, with many patients responding well to one drug class but not to another.

- The amount of BP reduction rather than the specific antihypertensive drug is the major determinant in reducing CV risk in hypertensive patients.25,26 However, this may not be the case with β-blockers and certain medication combinations.

- In the general non-Black (i.e., lacking specific overriding indications) population, initial medication management should include a thiazide diuretic, calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).4

- In the general Black population (i.e., lacking specific overriding indications), initial management should include a thiazide diuretic or CCB.4,27,28

- β-Blockers should not be considered first-line therapy in patients without evidence-based indications due to the lack of consistent data supporting an independent positive effect on CV morbidity and mortality and relatively less stroke protection compared to other first-line agents.4,29–31

- While the ALLHAT trial did demonstrate greater benefit of chlorthalidone (CTDN) in terms of HF, the JNC 8 did not conclude that this finding was compelling enough to recommend thiazide diuretic above the other first-line agents.4,27

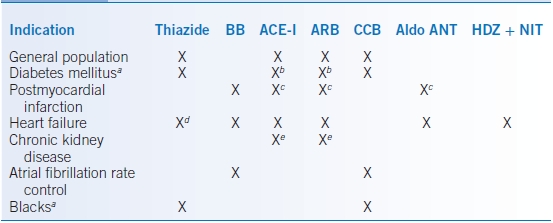

- Many patients have specific indications for particular antihypertensive agents based on other comorbidities (Table 6-4).3 Data regarding these indications are discussed in the appropriate sections below.

- A patient with mild HTN who is relatively unresponsive to one drug has an almost 50% likelihood of responding to a second drug, so trials of different agents are warranted before moving to combination therapy.32

- Many patients will not reach treatment goal BP on one drug.3,4

- The typical decrease in BP with a single agent is approximately 8 to 15 mm Hg systolic and 8 to 12 mm Hg diastolic.33,34 Most patients with HTN, however, will eventually require two or more medications.3,4

- Combination therapy is appropriate if BP cannot be controlled with a single agent, in patients with stage 2 HTN, and in patients with specific indications for multiple agents (Table 6-4).

- Thiazide diuretics, CCBs, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs are all appropriate add-on agents.4

- Fixed-dose combination pills offer the advantage of convenience that may improve adherence but sometimes at a higher cost to the patient and with less flexibility in adjusting doses.

TABLE 6-4 Indications for Individual Drug Classes

aCombination therapy frequently required.

bFirst-choice agent according to the American Diabetes Association.

cIn patients with left ventricular dysfunction.

dLoop rather than thiazide diuretic.

eParticularly for patients with albuminuria ≥30 mg/day (or albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g).

ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; Aldo ANT, aldosterone antagonist; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, β-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; HDZ, hydralazine; NIT, nitrate.

Data from Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72.

Specific Patient Populations

- Diabetes

- HTN occurs more frequently in diabetics compared with nondiabetics. These two conditions together significantly increase a patient’s risk of developing both major CV events and microvascular disease.

- The JNC 8 BP treatment goals are the same a nondiabetics (i.e., <140/90).4

- The American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2014 standards of care, however, recommend a goal of <140/80.35 An SBP of <130 is suggested for some patients (e.g., relatively young) if this can be attained without significant treatment burden.35

- The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) demonstrated a reduction in mortality (15%), MI (11%), and retinopathy/nephropathy (13%) for every 10 mm Hg reduction in SBP.36

- The JNC 8 recommendation regarding which particular drug to use/start in diabetics is the same as for nondiabetics, based on the lack of difference in CV outcomes.4

- The ADA specifically recommends that an ACE inhibitor or an ARB should be a component of antihypertensive treatment given their ability to retard loss of renal function and proteinuria independent of antihypertensive effects.35,37–40

- Most hypertensive diabetics will require more than one antihypertensive to achieve goal BP.

- HTN occurs more frequently in diabetics compared with nondiabetics. These two conditions together significantly increase a patient’s risk of developing both major CV events and microvascular disease.

- Ischemic heart disease

- β-Blockers reduce mortality following MI and should be initiated in all patients regardless of left ventricular (LV) function. Immediate therapy should be avoided in acute MI patients with signs HF or risk factors for cardiogenic shock.41–44

- β-Blockers without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity are preferred; therefore, acebutolol and pindolol should not be used. When LV function is impaired (without evidence of unstable HF or shock), β-blockers with proven benefit in HF should be used (i.e., metoprolol, carvedilol, and bisoprolol).41,42,44

- ACE inhibitors also have mortality benefit in patients following an MI, especially those with impaired LV function.41,42,45–48 An ARB may be substituted for patients intolerant to ACE inhibitors. Combined ACE inhibitor and ARB does not have further benefit and is associated with more adverse events. Perindopril has also been shown to decrease CV events in patients with stable CAD.49

- CCBs may be used if β-blockers are contraindicated or if additional BP or angina control is necessary. A long-acting dihydropyridine is recommended to limit the risk of heart block, bradycardia, and reflex tachycardia.

- β-Blockers reduce mortality following MI and should be initiated in all patients regardless of left ventricular (LV) function. Immediate therapy should be avoided in acute MI patients with signs HF or risk factors for cardiogenic shock.41–44

- Heart failure

- ACE inhibitors, ARBs, β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and the combination of hydralazine and nitrates have all been shown to have mortality benefit in HF, depending on disease severity.50–58

- Extended release metoprolol succinate, carvedilol, and bisoprolol all have proven benefit and are the preferred β-blockers.

- The addition or an ARB to ACE inhibitor therapy may be useful in some patients but patients should be monitored carefully for hyperkalemia, worsening renal function, and hypotension.59,60 The concomitant use of an ACE inhibitor, ARB, and aldosterone antagonist is not recommended.

- Loop diuretics constitute an important aspect of fluid management and are typically an essential part of the patient’s regimen.

- While CCBs may cause adverse effects due to their negative inotropic properties, long-acting dihydropyridines can provide additional BP control with less potential for myocardial depression than with verapamil and diltiazem.

- ACE inhibitors, ARBs, β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and the combination of hydralazine and nitrates have all been shown to have mortality benefit in HF, depending on disease severity.50–58

- Chronic kidney disease

- The JNC 8 BP goal for patients with CKD is the same as for the general population, <140/90.4

- The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Working Group, however, recommends a more strict goal of <130/80 for patients with CKD not on dialysis and with albuminuria ≥30 mg/day (or albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g or proteinuria ≥150 mg/day). Data most strongly support this goal for those with albuminuria ≥300 mg/day. The more lenient goal of <140/90 is recommended by KDIGO when albuminuria is <30 mg/day.61

- The National Kidney Foundation accepts these recommendations as reasonable but points out the lack of quality supporting data for the more stringent goals, particularly in those with moderate albuminuria (i.e., 30 to 300 mg/g).62

- KDIGO recommends that an ACE inhibitor or an ARB are first-line therapy in patients with albuminuria ≥30 mg/day (or albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g), particularly in those with concurrent DM.36–40,63–65 Again the data most strongly support this recommendation in those with albuminuria ≥300 mg/day.

- While adding an ARB to an ACE inhibitors reduces proteinuria more, data indicate that this may worsen outcome.66,67

- The JNC 8 BP goal for patients with CKD is the same as for the general population, <140/90.4

- Stroke

- During the acute phase of an ischemic stroke (at least the first 24 hours), BP is often increased and is generally not treated unless it is severely elevated (>220/120 mm Hg) or there is other ongoing end-organ damage (e.g., myocardial ischemia, HF, dissection, acute kidney injury [AKI], encephalopathy).68 An important exception is for patients who are to receive fibrinolytic therapy, in which case the BP should be lowered to <185/110 mm Hg and then to <180/105 mm Hg once it has been given. When to start or resume chronic antihypertensive therapy after an acute ischemic stroke is a matter of controversy; in most patients it is reasonable to initiate treatment after the first 24 hours.

- The acute management of BP in intracerebral hemorrhage is more complex and the BP can be extremely high in this circumstance. Guidelines recommend treatment for SBP >180 mm Hg (mean arterial pressure >130 mm Hg), with the aggressiveness of therapy and monitoring dependent on the degree of elevation and the concern for increased intracranial pressure.69 With an acute subarachnoid hemorrhage antihypertensive treatment is very generally recommended to decrease SBP <160 mm Hg.70

- Treatment of HTN to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke or TIA is clearly indicated.71–73 The PROGRESS trial demonstrated a reduction in recurrent stroke and all CV events in patients treated with perindopril and indapamide compared to placebo. The degree of reduction was dependent on the degree of BP lowering, which was most notable in the combined therapy patients.74 Some patients had preexisting HTN and others did not. The same has been shown for indapamide alone.72 A very large trial found no such difference with telmisartan versus placebo but the degree of achieved BP reduction was very small.75 Whether the class of drug used is as or more important than the degree of BP lowering has yet to be clearly determined, particularly for combination therapy. Both the JNC 8 and the American Stroke Association (ASA) recommend initiating treatment in patients with a prior stroke or TIA for BP ≥140/90 mm Hg and for a goal BP of <140/90 mm Hg.4,73

- During the acute phase of an ischemic stroke (at least the first 24 hours), BP is often increased and is generally not treated unless it is severely elevated (>220/120 mm Hg) or there is other ongoing end-organ damage (e.g., myocardial ischemia, HF, dissection, acute kidney injury [AKI], encephalopathy).68 An important exception is for patients who are to receive fibrinolytic therapy, in which case the BP should be lowered to <185/110 mm Hg and then to <180/105 mm Hg once it has been given. When to start or resume chronic antihypertensive therapy after an acute ischemic stroke is a matter of controversy; in most patients it is reasonable to initiate treatment after the first 24 hours.

- Black patients

- HTN is more common, is more severe, and has a higher morbidity in Blacks compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

- Blacks have lower plasma renin levels, increased plasma volume, and higher peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) compared with non-Black patients.

- Dietary sodium reduction may be more effective in this population with a greater decrease in BP compared with other demographic groups.76,77

- The JNC 8 does not make a specific BP target recommendations based solely on race and, therefore, treatment goals are the same as for non-Blacks.

- The 2010 International Society on Hypertension in Blacks (ISHIB) Consensus Statement recommends a goal of <135/85 for those with no evidence of end-organ damage, preclinical CVD, or overt CVD. A goal of <130/80 is recommended for Blacks with evidence of end-organ damage, preclinical CVD, or a history of CV events. In this context, end-organ damage was defined as albumin/creatinine ratio >200 mg/g, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/minute/1.73 m2, or ECG or echocardiographic evidence of LVH. CV events were defined as HF, CAD, MI, PAD, stroke, TIA, or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Preclinical CVD was defined as metabolic syndrome, Framingham risk >20%, prediabetes, or DM.28

- JNC 8 recommends either a thiazide diuretic or CCB as first-line therapy for Blacks, including those with DM.4,27 ISHIB emphasizes the common necessity of combined therapy in Blacks.28

- While Blacks in general have less of a BP reduction with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, they can still be very effective, particularly when combined with a diuretic or dihydropyridine CCB.7,28 The ACE inhibitor and CCB (rather than thiazide diuretic) combination may be particularly effective at reducing CV outcomes.78

- HTN is more common, is more severe, and has a higher morbidity in Blacks compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

- Older patients

- HTN becomes much more common with advancing age (>60), particularly isolated systolic HTN (i.e., SBP >140 and DBP <90). SBP may be a stronger predictor of CV events than DBP.

- Data from clinical trials clearly support treating HTN in older patients.21–24,79

- In elderly patients starting with lower doses and titrating slowly is, in general, reasonable advice. Care should be taken when increasing medications to avoid causing orthostatic hypotension and its symptoms. Following the standing BP may be helpful.80

- When treating isolated systolic HTN it is generally agreed that there is no increased risk in lowering the DBP until it is <60.7

- Thiazide diuretics, long-acting dihydropyridine CCBs, and ACE inhibitors/ARBs are all reasonable choices for initial therapy in older patients.4

- The effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment in frail older patients is unknown.

- HTN becomes much more common with advancing age (>60), particularly isolated systolic HTN (i.e., SBP >140 and DBP <90). SBP may be a stronger predictor of CV events than DBP.

Specific Drug Classes

- Thiazide diuretics

- Thiazides commonly used for HTN include hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), CTDN, and indapamide. They are a reasonable first choice for most patients.4

- Thiazides block sodium reabsorption at the distal convoluted tubule by inhibition of Na-Cl cotransporter, thereby decreasing plasma volume. Plasma volume, however, stabilizes after 2 to 3 weeks of therapy and partially returns to the pretreatment level. Therefore, the actual mechanism of sustained BP reduction is uncertain but may be due to a decrease in vascular resistance.

- CTDN is thought to be 1.5 to 2 times more potent than HCTZ and has a much longer half-life.

- They may be particularly effective in Blacks and the elderly who have a greater tendency to be sodium sensitive but are less effective in patients with renal insufficiency (eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2). In the latter case, a loop diuretic may be more appropriate.

- Multiple trials have shown thiazides to be effective in lowering BP, preventing initial and subsequent strokes, and reducing CV mortality.21,27 These data are largely driven by the use of CTDN in the ALLHAT trial, while the data supporting a reduction in CV events with HCTZ are minimal.27

- There is no randomized prospective trial data that specifically and directly compares the effectiveness of CTDN and HCTZ. A large network meta-analysis indirectly compared the two drugs and found CTDN to be superior in preventing CV events, even when the achieved SBP reduction was the same.81 Conversely, a large observational cohort did not find a difference in CV outcomes but did demonstrate a greater risk of hypokalemia with CTDN.82

- The results of the ACCOMPLISH Trial indicate that the combination of HCTZ plus benazepril is inferior to amlodipine plus benazepril.78 Given that many patients require combination therapy to achieve BP goals, these results could call into question the first-line drug of choice status of thiazides, particularly HCTZ, as CTDN was not studied in this trial.

- Side effects include electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypercalcemia, and hyperuricemia), muscle cramps, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance. Electrolyte monitoring is warranted during initiation, dosage changes, and occasionally when on stable treatment.

- Thiazides commonly used for HTN include hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), CTDN, and indapamide. They are a reasonable first choice for most patients.4

- Potassium-sparing diuretics

- Spironolactone and eplerenone inhibit the action of aldosterone by blocking the mineralocorticoid receptors in the cortical collecting ducts. Eplerenone is far more selective than spironolactone and does not have antiandrogenic or progestogenic effects. Amiloride and triamterene block the epithelial sodium channel and inhibit the reabsorption of sodium and secretion of potassium in the collecting ducts.

- Spironolactone and eplerenone are specifically indicated for patients with HF and reduced LV function after MI to improve morbidity and mortality.55,58,83

- Patients with primary hyperaldosteronism who refuse or are not candidates for surgery can be treated with potassium-sparing diuretics. Spironolactone and eplerenone have the advantage of fully blocking the systemic effects of aldosterone rather than counteracting its effect only in the collecting ducts.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics are sometimes added to thiazides to offset the hypokalemic effect of the latter.

- All potassium-sparing diuretics can cause hyperkalemia and monitoring of potassium and renal function is advisable, particularly in patients with DM and/or CKD. Spironolactone can cause gynecomastia, decreased libido, and impotence in men and mastodynia and amenorrhea in women.

- Spironolactone and eplerenone inhibit the action of aldosterone by blocking the mineralocorticoid receptors in the cortical collecting ducts. Eplerenone is far more selective than spironolactone and does not have antiandrogenic or progestogenic effects. Amiloride and triamterene block the epithelial sodium channel and inhibit the reabsorption of sodium and secretion of potassium in the collecting ducts.

- Loop diuretics

- Loop diuretics inhibit sodium resorption by blocking the Na-K-Cl cotransporter in the ascending loop of Henle and include furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, and ethacrynic acid. Ethacrynic acid does not contain a sulfa moiety and can be used in those with a sulfa allergy.

- Short-acting loop diuretics should not generally be considered antihypertensive agents in patients without CKD.

- They are appropriate antihypertensives for patients with HTN and eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2 because hypervolemia is often an important factor.

- Side effects include electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hyperuricemia), ototoxicity (less common with oral rather than intravenous), and glucose intolerance.

- Loop diuretics inhibit sodium resorption by blocking the Na-K-Cl cotransporter in the ascending loop of Henle and include furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, and ethacrynic acid. Ethacrynic acid does not contain a sulfa moiety and can be used in those with a sulfa allergy.

- ACE inhibitors

- Commonly used ACE inhibitors include benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril, and trandolapril.

- As the name clearly implies, these drugs inhibit ACE leading to a decreased conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which reduces vasoconstriction, reduces aldosterone secretion, promotes natriuresis, and increases vasodilatory bradykinins.

- ACE inhibitors are appropriate initial therapy in most patients.4

- ACE inhibitors are considered first-line therapy in patients with HF or asymptomatic LV dysfunction, prior MI or high risk for CAD, DM, and CKD with moderate-to-severe albuminuria.36–38,45–47,51,63,65,84,85

- They work well in combination with other agents, particularly diuretics, due to the activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). As noted above, however, the results of the ACCOMPLISH Trial indicate that the combination of benazepril plus HCTZ is inferior to benazepril plus amlodipine.78 CTDN was not studied in this trial.

- While adding an ARB to an ACE inhibitor further reduces proteinuria, data indicate that this may worsen outcome.66,67

- ACE inhibitors are absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy.

- Side effects include hyperkalemia, orthostatic hypotension, cough, angioedema, and worsening renal function. However, an increase in serum creatinine is expected in most patients and up to 30% is acceptable and not a reason to discontinue therapy.

- Commonly used ACE inhibitors include benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril, and trandolapril.

- ARBs

- The ARBs include candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, and valsartan. These drugs directly block angiotensin II receptors resulting in vasodilation. They do not inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin and are much less likely to cause cough.

- ARBs are appropriate as initial therapy in most patients and generally effective in the same clinical settings as an alternative to ACE inhibitors.39,40,48,56,57

- ARBs may be specifically beneficial in patients with LVH.31

- While adding an ARB to an ACE inhibitor further reduces proteinuria, data indicate that combined therapy does not improve CV outcome and may worsen renal outcome.66,67

- ARBs are absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy.

- Side effects are similar to those of ACE inhibitors and include hypotension and a lower incidence of cough and angioedema.

- The ARBs include candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, and valsartan. These drugs directly block angiotensin II receptors resulting in vasodilation. They do not inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin and are much less likely to cause cough.

- Direct renin inhibitors

- Aliskiren binds the active site of renin and inhibits the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I and subsequently dramatically reducing the levels of angiotensin II and aldosterone.

- Aliskiren is effective at lowering BP and has been studied as monotherapy and in combination with other drugs.86–88

- One study showed that the addition of aliskiren to losartan in patients with diabetic nephropathy may further reduce albuminuria.89 A subsequent randomized controlled trial in a much larger but similar population was terminated early due to a trend toward more stroke, hypotension, hyperkalemia, and a lack of benefit on CV and renal outcomes.90

- At present, there are no long-term studies demonstrating a reduction in long-term hard CV or renal outcomes with aliskiren. It should not be used as first-line therapy.

- Side effects include hyperkalemia, decreased renal function, diarrhea, and cough.

- Aliskiren binds the active site of renin and inhibits the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I and subsequently dramatically reducing the levels of angiotensin II and aldosterone.

- Calcium channel blockers

- CCBs selectively block the slow inward calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle causing arteriolar vasodilation.

- Long-acting dihydropyridine CCBs (e.g., amlodipine, felodipine, isradopine, nifedipine) are most commonly used for HTN while the nondihydropyridine CCBs (e.g., verapamil and diltiazem) are used for atrial fibrillation rate control and angina. CCBs are also indicated for coronary vasospasm or Raynaud phenomenon, and supraventricular arrhythmias.

- CCBs are appropriate as an initial treatment of HTN in most patients.4,27

- They may be particularly effective in older patients with isolated systolic HTN and Blacks.3,27,28

- As a class, CCBs have no significant effect on glucose tolerance, electrolytes, or lipid profiles and are not adversely affected by NSAIDs.

- Side effects include flushing, headache, dependent edema, gingival hyperplasia, and esophageal reflux.

- CCBs selectively block the slow inward calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle causing arteriolar vasodilation.

- β-Blockers:

- β-Blockers competitively inhibit the effects of catecholamines at β receptors to decrease heart rate and cardiac output. Individual drugs have variable selectivity for β1 and β2 receptors. β1 receptors are located mainly in the heart and kidneys. β2 receptors are found in the lungs, vascular smooth muscle (causing vasodilation), gastrointestinal (GI) tract, uterus, and skeletal muscle. Some β-blockers also have antagonistic effects on α1 receptors. They also decrease plasma renin and release vasodilatory prostaglandins. The precise mechanism of sustained BP reduction, however, is uncertain.

- The nonselective β-blockers antagonize both β1 and β2 receptors and include propranolol, timolol, and nadolol. There is some risk of bronchospasm in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or reactive airway disease. There is a theoretical possibility of hypoglycemia and blunting of the adrenergic response to hypoglycemia.

- Cardioselective β-blockers primarily act on β1 receptors but lose some selectivity at higher doses. Examples include atenolol, bisoprolol, esmolol, and metoprolol. They seem to have less risk of inducing bronchospasm.

- Some β-blockers are said to have intrinsic sympathomimetic activity including acebutolol and pindolol. They exert low-level agonist activity while simultaneously antagonizing the site. Acebutolol is β1-selective and pindolol is nonselective. These drugs may be useful in patients with excessive bradycardia but do not have demonstrated benefit in patients post-MI.

- The mixed α- and β-blockers labetalol and carvedilol have antagonist effects at both types of adrenergic receptors. Both have vasodilating properties through α1-receptor blockade.

- Nebivolol is a new vasodilating β-blocker with and additional unique mechanism of action—potentiating nitric oxide (NO).

- The vasodilating β-blockers may be preferential to conventional nonselective β-blockers based on the latter being associated with inferior outcomes, an increased rate of stroke, and an increased risk of developing DM.29 On the other hand, it is important to note that to date there are no long-term outcome trials of vasodilating β-blockers used solely for the treatment of HTN.

- β-Blockers are no longer considered appropriate first-line agents for patients without compelling indications (e.g., MI or HF) due to the lack of data supporting an independent positive effect on morbidity and mortality.4,29,30

- β-Blockers reduce mortality following MI and should be initiated in all patients regardless of left ventricular (LV) function. β-blockers without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity are preferred. When LV function is impaired (without evidence of unstable HF or shock), β-blockers with proven benefit in HF should be used (i.e., metoprolol, carvedilol, and bisoprolol).41–43

- β-blockers have been clearly shown to have mortality benefit in HF, particularly metoprolol, carvedilol, and bisoprolol.52–54

- β-blockers are also indicated for the treatment of tachyarrhythmias and angina.

- Side effects of β-blockers include fatigue, nausea, dizziness, heart block (especially when used with CCBs), worsening of HF, dyslipidemia, erectile dysfunction, and bronchospasm. Abrupt withdrawal can precipitate angina and elevation of BP because of the increase in adrenergic tone with chronic β-blocker use.

- β-Blockers competitively inhibit the effects of catecholamines at β receptors to decrease heart rate and cardiac output. Individual drugs have variable selectivity for β1 and β2 receptors. β1 receptors are located mainly in the heart and kidneys. β2 receptors are found in the lungs, vascular smooth muscle (causing vasodilation), gastrointestinal (GI) tract, uterus, and skeletal muscle. Some β-blockers also have antagonistic effects on α1 receptors. They also decrease plasma renin and release vasodilatory prostaglandins. The precise mechanism of sustained BP reduction, however, is uncertain.

- α1-Blockers:

- Prazosin, terazosin, and doxazosin block α1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells, impairing catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction.

- α1-Blockers are less efficacious than thiazides, CCBs, and ACE inhibitors as monotherapy based on the ALLHAT and are not recommended as first-line therapy.27

- They are characterized by a first-dose effect with a larger decrease in BP than subsequent doses making use before bedtime more appropriate than the morning.

- They may decrease urinary symptoms in patients with prostate enlargement.

- Side effects include orthostatic hypotension, GI distress, and drowsiness.

- Prazosin, terazosin, and doxazosin block α1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells, impairing catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction.

- Centrally acting adrenergic agonists

- Clonidine and methyldopa stimulate α2 receptors in the central nervous system leading to decreased peripheral sympathetic tone, PVR, heart rate, and cardiac output. Both are effective antihypertensives, but there are no long-term outcome data supporting either drug.

- Clonidine can be quite useful for hypertensive urgencies. Refer to the Hypertension Urgencies and Emergencies section.

- Abrupt cessation can precipitate an acute withdrawal syndrome characterized by tachycardia, diaphoresis, and severe elevations in BP.

- Methyldopa is safe in pregnancy.

- Side effects include bradycardia, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, depression, and sexual dysfunction. Methyldopa is associated with a lupus-like syndrome.

- Clonidine and methyldopa stimulate α2 receptors in the central nervous system leading to decreased peripheral sympathetic tone, PVR, heart rate, and cardiac output. Both are effective antihypertensives, but there are no long-term outcome data supporting either drug.

- Other sympatholytic agents such as reserpine, guanethidine, and guanadrel are no longer considered first- or second-line therapy because of their significant side effect profiles and the availability of more effective and much better-tolerated drugs.

- The so-called direct-acting vasodilators are hydralazine and minoxidil.

- These agents hyperpolarize arteriolar smooth muscle by activating gated potassium channels to produce direct relaxation and, therefore, vasodilation. Hydralazine requires the presence of NO to be functional and minoxidil contains a NO moiety.

- While these are potentially potent antihypertensive agents, there are no randomized clinical trials demonstrating improvements in CV morbidity and mortality with either drug when used specifically for HTN. Because of this, both are second-line therapy. Additionally, they have the potential for more frequent and significant side effects.

- Hydralazine plus nitrate improves mortality in patients with HF compared to placebo.50 Further evidence indicates that ACE inhibitor therapy is more beneficial than the combination of hydralazine and nitrate in HF patients.91 In Blacks, the addition of hydralazine and nitrate to standard HF therapy (including RAS blockade and β-blockers) further improves mortality.92 Whether these effects are ethnically specific is unresolved. Care should be taken not to conflate these results with the use of hydralazine strictly as an antihypertensive. Additionally, oral nitrates are not appropriate for use as an ongoing BP-lowering agent.

- Both hydralazine and minoxidil may lead to reflex sympathetic hyperactivity and fluid retention that makes concomitant treatment with a diuretic and/or β-blocker desirable.

- Side effects of hydralazine include headache, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, GI distress, and a lupus-like syndrome. Minoxidil can lead to weight gain, hirsutism, hypertrichosis, ECG abnormalities, and pericardial effusions.

- These agents hyperpolarize arteriolar smooth muscle by activating gated potassium channels to produce direct relaxation and, therefore, vasodilation. Hydralazine requires the presence of NO to be functional and minoxidil contains a NO moiety.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapy

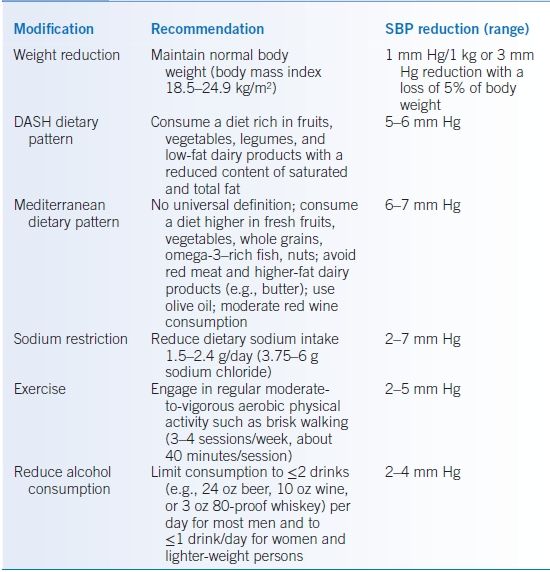

- Therapeutic lifestyle changes described in Table 6-5 should be instituted in all patients with HTN and prehypertension.3,7,19,20 These represent a critical component of both prevention and management of those on drug therapy.

- Therapeutic lifestyle changes may be employed as sole therapy for 6 to 12 months to manage stage 1 HTN in the absence of DM, end-organ damage, evidence of CVD, or multiple other risk factors.3,7,19

- Weight loss results in a reduction of SBP on the order of 1 mm Hg/kg. Put another way, a 5% weight loss results in about a 3 mm Hg reduction in SBP.93–96 Orlistat and sibutramine increase weight loss but the former my increase BP.93

- Exercise: Moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity 3 to 4 sessions/week, 40 minutes/session results in a 2 to 5 and 1 to 4 mm Hg reduction in SBP and DBP, respectively, independent of weight loss.20

- Diet

- Reducing sodium levels decreases BP in some individuals but often enhances the antihypertensive effects of medications. Sodium intake should be restricted to 1.5 to 2.4 g/day (3.75 to 6 g sodium chloride). This degree of restriction may reduce SBP by 2 to 7 mm Hg.20

- The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and a Mediterranean diet pattern may be recommended.20,97 The DASH diet consists of consuming a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and low-fat dairy products with a reduced content of saturated and total fat. Adding sodium limitation to the DASH diet augments BP reduction.76

- There is no universal definition of the Mediterranean dietary pattern. In general, it entails consuming a diet higher in fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, omega-3–rich fish, nuts, and avoiding red meat and higher-fat dairy products (e.g., butter). Olive oil is the typical fat. It also often includes moderate red wine consumption.

- Reducing sodium levels decreases BP in some individuals but often enhances the antihypertensive effects of medications. Sodium intake should be restricted to 1.5 to 2.4 g/day (3.75 to 6 g sodium chloride). This degree of restriction may reduce SBP by 2 to 7 mm Hg.20

- Cessation of tobacco smoking is advised for overall CV health but does not reduce basal BP.

- Alcohol intake should be limited to ≤2 drinks/day for men and ≤1 drink/day for women and smaller men. Restricting alcohol to these levels can reduce SBP by 2 to 4 mm Hg.20 One drink is equivalent to 12 oz beer (350 mL), 5 oz wine (150 mL), or 1.5 oz 80-proof whiskey (45 mL).

- Although relieving stress may improve one’s overall health, no studies have successfully demonstrated a link between stress reduction and a sustained reduction in BP.

TABLE 6-5 Lifestyle Modifications to Prevent and Reduce Hypertension

DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

Modified from Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree