Chapter 55 Many national organizations, such as the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the Endocrine Society, the American College/Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH), the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), along with the FDA, support the use of HT for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy associated with menopause. Most of these organizations and the FDA recommend against the use of HT for prevention of chronic disease (e.g., cardiovascular disease), with the exception of osteoporosis. However, they note that other options are also available for osteoporosis prevention and should be considered in women who do not experience moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (see Chapter 39). Additionally, current recommendations for HT use advocate using the lowest effective dose and, in most cases, for the shortest length of time. Women who use HT should regularly review their symptoms with their clinicians to consider the need for continued use. The WHI results indicate that HT use for 3 to 5 years is reasonably safe. The risks vs. benefits for use, especially for longer periods, must be determined on an individual basis. The NAMS states that there is no clear data regarding length of therapy, and the International Menopause Society (IMA) notes that there is no reason to place a specified limit on the length of therapy. See Chapter 54 for a discussion of hormone use during the reproductive years. Loss of bone mass is associated with postmenopause. Bone density peaks in the early to mid 30s and then begins to decline slowly over time. Loss accelerates following menopause at a rate of 1% to 5% per year for the first 4 to 8 years after menopause; it then slows again to a rate of about 1% per year. This loss of bone mass can lead to osteopenia and osteoporosis, which predispose women to fracture; it is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. See Chapter 39 for further discussion. Monitoring FSH levels for the purpose of diagnosing menopause is not recommended. Identification of menopause is based on symptom patterns, menstrual changes, and age. Most clinicians do some laboratory testing to rule out other conditions that can mimic menopausal symptoms, such as thyroid abnormalities (see Chapter 52) or diabetes (see Chapter 53). If the woman is perimenopausal, FSH levels are especially unreliable because of the irregularity of hormone levels during this phase. FSH levels may be high when tested and then may fall low enough to allow for ovulation and pregnancy. Progestogens include bioidentically manufactured progesterone and a number of other synthesized manufactured progestogens and synthesized compounded progestogens. Common major classes of synthetic progestogens are the 17 acetoxyl-progestin derivatives (21-carbon atoms; e.g., medroxyprogesterone), which are very similar to the endogenous hormone (e.g., micronized progesterone); micronized progesterone; and the 19-nortestosterone compounds (e.g., norethindrone), which have both progestogen effects and a variety of androgenic effects. Progestogens are lipophilic and bind to progesterone receptors throughout the body. See Chapter 53 for more information on progestogens. • North American Menopause Society: The 2012 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society, Menopause 19(3):257-271, 2012. • Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Ginzburg SB et al: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause, Endocr Pract 12(3):315-337, 2006. • Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP et al: Postmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statement, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(7 Suppl 1):s1-s66, 2010. • Sturdee DW, Pines A, Archer DF et al: Updated IMS recommendations on postmenopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health, Climacteric 14(3):302-320, 2011. • The Endocrine Society: Androgen therapy in women, 2006. See www.endo-society.org. • AHQR Evidence Report on Managing Menopause-Related Symptoms, 2005. • Pregnancy is possible during the perimenopausal years; these women must be counseled for appropriate selection of contraception if needed. • Menopause-related symptom management begins with lifestyle modification. • Use of HT must be individualized for each specific woman. • The decision to use HT must be made in partnership with each individual woman, with consideration given to therapy risks and benefits, QOL, personal and family history, and personal preferences. • HT should be given at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest time possible. • The need for therapy must be regularly reevaluated. • HT is used in conjunction with lifestyle changes to manage moderate to severe vasomotor and vulvovaginal symptoms associated with menopause in postmenopausal women. The following recommendations are supported by most national organizations and the FDA. • Progesterone is needed for all women who have an intact uterus. Progesterone is used for the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in postmenopausal women with an intact uterus who are using estrogen. Women in the United States increasingly seek complementary and alternative therapies for the management of symptoms of menopause. Data regarding efficacy are limited, and, with the possible exception of black cohosh, few therapies have consistently demonstrated benefits. Black cohosh is a herb that has estrogen-like effects. It has shown efficacy in managing menopause-related symptoms in some studies and not in others. Women who have contraindications for taking estrogen should not use black cohosh. The exact mechanism of action of black cohosh is unclear. Recent publications suggest that no direct effect on estrogen receptors may be seen, although this is an area of controversy. Soy is a phytoestrogen, a plant substance that when ingested is metabolized into a compound that has estrogen-like properties. Complementary and alternative therapies are not regulated by the FDA in the same manner that prescription medications are. Purity, dose-to-dose or package-to-package consistency, and strength of varying forms of OTC products, herbal remedies, or soy formulations may fluctuate. Despite these potential limitations, many herbal products, soy formulations, and alternative practices (e.g., acupuncture) are used by women who experience symptoms. Research has indicated that stress management, such as deep-breathing exercises similar to yoga breathing, may help to alleviate or reduce the severity of hot flashes. Herbal and OTC products can interact with prescription medications and with each other; thus information on use of these products must be elicited and documented (see Chapter 8 for additional information on alternative therapies). Some women prefer medications other than HT for vasomotor symptom management. A significant body of research indicates that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, citalopram, and paroxetine, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, can effectively reduce vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Clonidine and gabapentin have also been shown to have some efficacy in vasomotor symptom relief, but clonidine is rarely used due to its side effect profile. None of these alternative medications is as effective as ET or HT. Estrogen agonists/antagonists such as tamoxifen and raloxifene have proved ineffective in reducing hot flashes. In fact, raloxifene may cause vasomotor symptoms in some women. Tamoxifen is frequently used for breast cancer treatment. Raloxifene is used for osteoporosis prevention and treatment and invasive breast cancer risk reduction (see Chapter 39 for additional information on osteoporosis and estrogen agonist-antagonists (or selective estrogen reuptake modulators, SERMs)). Low-dose OCs during the perimenopausal years are contraindicated in smokers (Box 55-1) because of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and VTE. OC use is associated with a reduced risk for developing ovarian and endometrial cancers. Research undertaken to evaluate the effects of OCs on breast cancer and stroke has yielded contradictory findings (see Chapter 53 for more information).

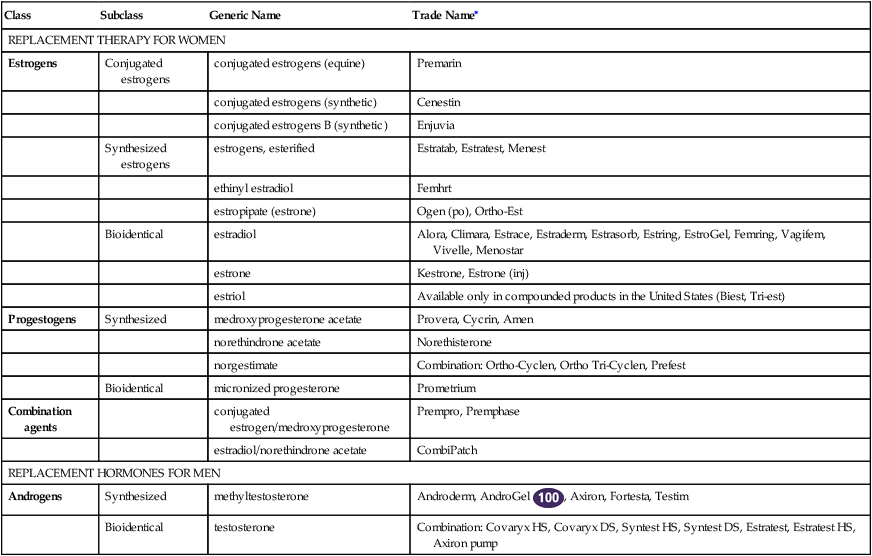

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Class

Subclass

Generic Name

Trade Name∗

REPLACEMENT THERAPY FOR WOMEN

Estrogens

Conjugated estrogens

conjugated estrogens (equine)

Premarin

conjugated estrogens (synthetic)

Cenestin

conjugated estrogens B (synthetic)

Enjuvia

Synthesized estrogens

estrogens, esterified

Estratab, Estratest, Menest

ethinyl estradiol

Femhrt

estropipate (estrone)

Ogen (po), Ortho-Est

Bioidentical

estradiol

Alora, Climara, Estrace, Estraderm, Estrasorb, Estring, EstroGel, Femring, Vagifem, Vivelle, Menostar

estrone

Kestrone, Estrone (inj)

estriol

Available only in compounded products in the United States (Biest, Tri-est)

Progestogens

Synthesized

medroxyprogesterone acetate

Provera, Cycrin, Amen

norethindrone acetate

Norethisterone

norgestimate

Combination: Ortho-Cyclen, Ortho Tri-Cyclen, Prefest

Bioidentical

micronized progesterone

Prometrium

Combination agents

conjugated estrogen/medroxyprogesterone

Prempro, Premphase

estradiol/norethindrone acetate

CombiPatch

REPLACEMENT HORMONES FOR MEN

Androgens

Synthesized

methyltestosterone

Androderm, AndroGel ![]() , Axiron, Fortesta, Testim

, Axiron, Fortesta, Testim

Bioidentical

testosterone

Combination: Covaryx HS, Covaryx DS, Syntest HS, Syntest DS, Estratest, Estratest HS, Axiron pump

Hormone Replacement Therapy for Women

Therapeutic Overview of Hormone Therapy

Anatomy and Physiology

Disease Process

Immediate-Onset Effects

Long-Term Effects

Bone Density

Assessment

Mechanism of Action

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic Treatment

Oral Contraceptives during Perimenopause

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Hormone Replacement Therapy