Hodgkin Lymphoma: Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant

Definition

A monoclonal B-cell neoplasm characterized by a nodular pattern, with or without diffuse areas, in which large neoplastic lymphocytic and/or histiocytic (L&H) cells are present against a background of numerous lymphocytes and histiocytes, and follicular dendritic cells in nodular areas (1).

Synonyms

Epidemiology

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) represents approximately 5% of all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), and 6.5% of all cases of HL, as reported by the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study (1,5). In the United States, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, from 1992 to 2001, NLPHL represented 3.2% of all cases of HL (6). These slight differences in frequency may be a reflection of geographic or genetic factors, or perhaps differences in case collection. In the SEER database, the incidence rate of NLPHL is 0.08 per 100,000 person-years (6). The disease affects males more frequently than females, in a ratio of up to 3:1, and whites more often than African Americans (6). Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL can occur at all ages, with a peak in incidence at 30 to 50 years of age (1,5,6).

Pathogenesis

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL traditionally has been included in the classifications of HL. However, with the advent of immunohistochemical analysis and subsequently single-cell polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies, it is clear that the L&H cells in NLPHL are of B-cell origin. Furthermore, the immunophenotype of L&H cells is dissimilar from the Reed-Sternberg and Hodgkin cells of other types of HL, known as classical HL. The L&H cells of NLPHL strongly express a variety of pan–B-cell antigens and transcription factors or cofactors, as well as germinal center B-cell–associated antigens and leukocyte common antigen (LCA; CD45). L&H cells are also almost always negative for CD15 and CD30 (1,5,7,8). Single-cell PCR studies of NLPHL cases have shown that L&H cells carry immunoglobulin (Ig) gene rearrangements with a high frequency of somatic mutations in the Ig variable region genes (9). These findings show that L&H cells are B cells of germinal-center cell origin with a functional B-cell differentiation program. This is not the case for those Reed-Sternberg and Hodgkin cells that occur in classical HL.

The etiology and pathogenetic mechanisms of neoplastic transformation in the L&H cells of NLPHL are largely unknown at this time. Progressive transformation of germinal centers (PTGC) has been suggested as a precursor lesion, and PTGC is found in approximately 20% of patients who have NLPHL, either involving the same lymph node or different lymph nodes. Progressive transformation of germinal centers can occur with NLPHL in either simultaneous or metachronous fashion (10,11). However, currently, no convincing data show that patients with PTGC have an increased risk of subsequent NLPHL, and PTGC can rarely occur in patients with classical HL.

Clinical Features

Patients with NLPHL most often present with lymph node enlargement and have localized disease (12,13,14). Peripheral lymph nodes are most frequently involved by NLPHL, most often in the cervical region, with axillary and inguinal lymph nodes also commonly involved. It is uncommon or rare for NLPHL to involve the thymus or lymph nodes in the mediastinal, hilar, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal regions (12,13,15). B-type symptoms are uncommon, occurring in fewer than 10% of patients (12,13,14,15). Fewer than 20% of patients with NLPHL present with high-stage disease. These patients have involvement of multiple lymph node groups, liver, spleen, bones, or bone marrow. However, in patients with high-stage disease, the possibility of transformation to large B-cell lymphoma must be excluded, and in our experience, bone marrow involvement usually occurs in patients who have already transformed to large B-cell lymphoma (16).

The clinical course of patients with NLPHL is indolent. Patients with localized disease and favorable prognostic features may be treated with involved-field radiotherapy without chemotherapy (9,10,17). In the pediatric age group, a “watch and wait” strategy has been used to avoid the complications of therapy. Rituximab (anti-CD20) also has been used in clinical trials, for patients with de novo or relapsed disease (18). However, for patients with unfavorable prognostic features or advanced stage, the current recommendation is that patients be treated as they are for classical HL. This usually involves a chemotherapy regimen that includes doxorubicin (Adriamycin), or Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) (12,13). Other chemotherapy regimens also are used (17).

Patients with NLPHL have an overall relapse rate that is similar to patients with classical HL. However, relapses tend to occur over a longer interval of time in NLPHL patients. The overall survival of NLPHL patients who relapse is better than for patients with classical HL who relapse (13). Patients with NLPHL are at risk of developing large B-cell lymphoma over time. This is discussed later in this chapter.

Histologic Features

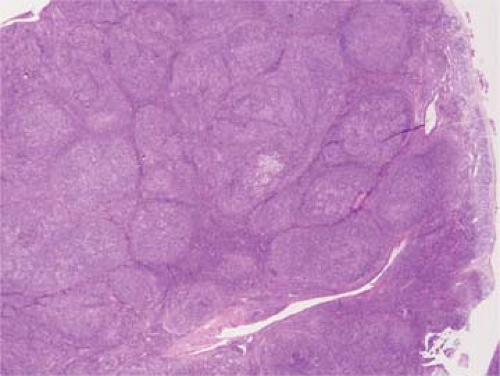

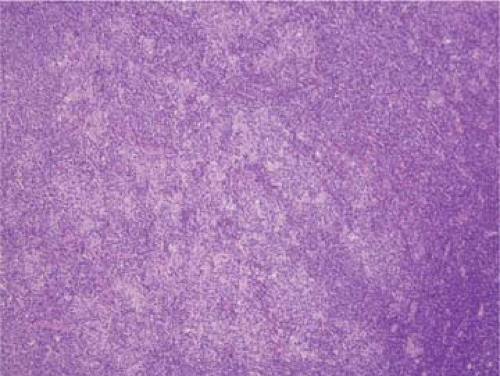

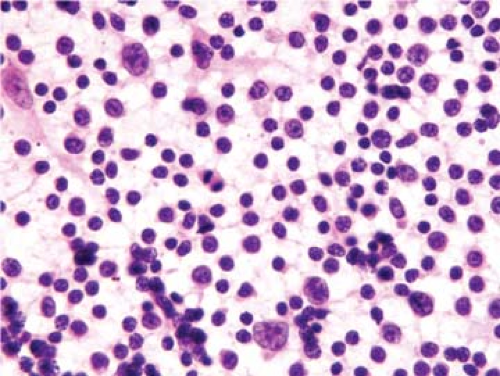

The classical pattern of NLPHL is that of large, expansile nodules that partially or totally replace the lymph node architecture (Fig. 58.1) (1,5,7,8,15). These nodules also displace and compress uninvolved lymphoid tissue at the periphery of the neoplasm. The neoplastic nodules vary in size, but most of them are larger than reactive lymphoid follicles, and they usually have vaguer outlines than do reactive follicles (Fig. 58.2). In well-developed cases of NLPHL, the nodules are typically arranged closely, often in back-to-back fashion. The neoplastic nodules are composed of numerous, small, round lymphocytes; typical and epithelioid histiocytes; follicular dendritic cells; and neoplastic L&H cells, with the latter representing 1% or less of all the cells in the nodules. L&H cells are large with scant pale cytoplasm (Fig. 58.3). Their nuclei are often multilobated or folded, and each nucleus usually has vesicular (or clear) nucleoplasm, an inconspicuous nucleolus, and a thin nuclear membrane. These cells often resemble popped kernels of corn and therefore the descriptive name “popcorn” cells is often used as a synonym for L&H cells. However, L&H cells can also have relatively round nuclear contours or more prominent nucleoli, with much less resemblance to popcorn. Mitoses are uncommon. The large size and distinctive cytologic features of L&H cells can be appreciated in fine needle aspirate smears and touch imprints (Fig. 58.4).

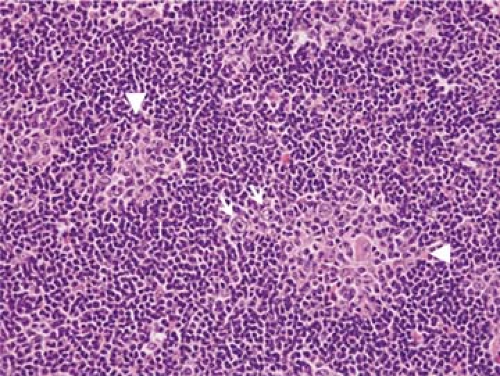

Reactive germinal centers are unusual in the nodules of NLPHL, but they can occur, in up to 15% of cases in one study (Fig. 58.5) (15). Epithelioid histiocytes are present, either singly or in small clusters, and in some cases can form wreaths around the periphery of the nodules. Fibrosis is usually absent in cases of NLPHL, but it can be present in approximately 20% of cases (15). Eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells are not a part of NLPHL. Classic Reed-Sternberg cells can occur in NLPHL,

but they are usually rare and are not required to establish the diagnosis. If classical Reed-Sternberg cells are numerous, a different diagnosis should be considered.

but they are usually rare and are not required to establish the diagnosis. If classical Reed-Sternberg cells are numerous, a different diagnosis should be considered.

Figure 58.5. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. In this case, small reactive germinal centers (arrowheads) can be identified within tumor nodules. L&H cells (arrows) also are present. (Same section shown in Figs. 58.13 A,B.) Hematoxylin and eosin stain. |

Variant patterns also have been described in NLPHL. Fan et al. (15) at Stanford University Medical Center have described six patterns: classic nodular, serpiginous/interconnected nodular, nodular with extranodular L&H cells, nodular with T-cell–rich background, T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma-like (also referred to as a diffuse pattern), and diffuse “moth-eaten” with a B-cell–rich background. Two or more of these patterns are commonly present in a biopsy specimen involved by NLPHL. The classic nodular pattern has already been described. The other patterns are referred to as variant patterns, and their recognition is essential because only variant patterns are present in approximately 5% to 10% of cases.

The term serpiginous/interconnected nodular pattern well describes the histologic findings. The nodules closely resemble the classic nodular pattern but their outlines are very irregular and fuse with other nodules. The nodular with extranodular L&H cells pattern also resembles the classic nodular pattern, except that a subset or most of the L&H cells occur are the periphery of the tumor nodules, outside of the follicular dendritic cell network (Fig. 58.6). This pattern may represent an early stage in progression to T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma (15). The term nodular with T-cell–rich background pattern also accurately reflects the histologic findings. The neoplasm is clearly nodular, but reactive small B cells are markedly decreased. Boudova et al. (5) also described this pattern (which they designated as pattern A), and they quantified the small B cells relative to L&H cells in their cases. Compared with the classic nodular pattern, in which the small B cell-to-L&H cell ratio ranges from 20:1 to 50:1, in the nodular T-cell–rich background pattern, this ratio ranges from 0.7:1 to 4.2:1 (5). This pattern has not been shown to influence prognosis (5,15).

The two variant patterns described by Fan et al. (15), in which a diffuse component is present, are distinctive and have different clinical implications. The T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma-like diffuse pattern is composed of scattered large L&H cells against a background of numerous T cells and histiocytes. Except for the coexistence of a component of nodular pattern in these cases, the findings otherwise resemble T-cell/histiocyte–rich large B-cell lymphoma, as defined in the WHO classification (see Differential Diagnosis) (1,15). The presence of this pattern in NLPHL was significantly associated with an increased relapse rate (15). The diffuse “moth-eaten” pattern with a B-cell–rich background, except for its diffuse pattern, otherwise resembles the classic nodular NLPHL cases. This variant pattern in NLPHL is uncommon, representing less than 5% of all cases, and is rarely present as a predominant pattern in a biopsy specimen. This pattern is too infrequent to reliably assess its impact on prognosis.

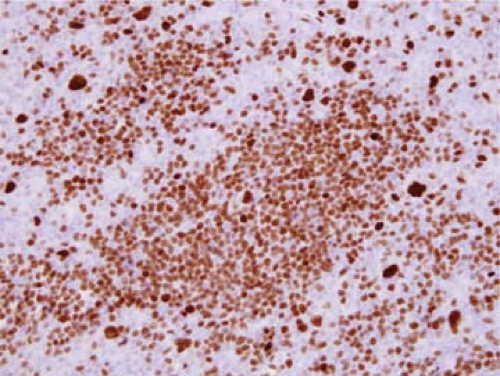

Figure 58.6. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Immunohistochemical stain for octamer binding transcription factor 2 (Oct2) highlights many small B cells and large L&H cells. Many of the L&H cells are outside of the tumor nodules, corresponding to the pattern referred to by Fan et al. (15) as nodular with extranodular L&H cells. Immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain. |

Gray Zone Neoplasms

The term gray zone lymphoma has been used differently by various authors, with perhaps its use being most frequent for neoplasms that have features of both classical HL and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma.

The gray zone terminology also has been used in the context of the differential diagnosis of NLPHL and T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (5). Boudova et al. (5) described 17 (7.2%) neoplasms in their series, in which the distinction between NLPHL and T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma could not be made using their histologic and immunohistochemical criteria. Morphologically, large neoplastic B cells were present within nodules that retained their follicular dendritic cell network, but these nodules were rich in T cells and histiocytes and markedly depleted of small B cells. Clinically, these patients had B symptoms and presented with high-stage clinical disease, resembling patients with T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; however, the lesions had an indolent clinical behavior more in keeping with patients with NLPHL.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree