Hodgkin Lymphoma: Classical

Definition

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is characterized by a heterogeneous cellularity comprising a minority of specific neoplastic cells—the Hodgkin cells and the Reed-Sternberg cells—and a majority of reactive non-neoplastic cells.

Synonym

Hodgkin disease.

Epidemiology

Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for about l% of all cancers (1) and 11.5% of all lymphomas diagnosed in 2007 (2). For that year, the projections in the United States were for 8,190 cases of HL and of 63,190 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (2).

The wide geographic variation in the incidence of HL supports the belief that the disease is caused by an environmental, probably infectious, agent (3). In the United States and western Europe, HL is a common form of cancer in young adults (4), with 3.5 to 5 cases occurring per 100,000 population per year in persons between the ages of 15 and 35 years (5). In Japan, the incidence is almost three times lower (6). In economically developed countries with a high standard of living, HL is rare in children and more frequent in young adults, displaying the histologic types that are associated with a favorable prognosis. In underdeveloped countries and populations with poor socio economic conditions, the incidence is highest in children, and the histologic types associated with a poor prognosis predominate (7).

In relation to age, the distribution curve is bimodal, with the first peak between 15 and 34 years and the second peak after 54 years (8). The incidence of HL among people younger than 20 years was 1.1 per 100,000 in 2004. In this age group, the incidence of HL has decreased steadily between 1975 and 1999 and has been more frequent in adolescents than in children (2).

By gender, HL occurs slightly more often in men than in women. Of the 8,190 cases in 2007, HL affected 4,470 males and 3,720 females (2). The overall ratio is 1.34:1.00; it is approximately equal in younger patients, and a male predominance was noted in a series of older patients (9).

Nodular sclerosis (NL) and lymphocyte-predominant, the histologic types with a favorable prognosis, are significantly more common in younger persons and in women (10,11,12,13). The survival rates for HL have improved continuously from 78% at 5 years in 1976 to 94% in 1998 (14).

In acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients and transplant recipients, HLs are far less common than NHLs (15,16). The incidence of HL is significantly increased, and AIDS patients carry a risk 10 times greater than that of persons without AIDS (17). Yet the incidence of NHLs in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive persons is 300 times higher than in normal individuals (17,18).

Etiology

Extensive investigations directed at a variety of etiologic factors have failed so far to reveal the cause of HL. Clusters of HL cases have been reported in families and in social groups of unrelated persons, observations that focus attention on genetic and other host factors and, alternately, on various environmental agents (9,19).

Epidemiologic studies indicate a relationship with infectious mononucleosis (IM), which is associated with a fourfold increased risk for the subsequent development of HL (20).

A study investigating this relationship in a large cohort of patients with prior IF concluded that only those who had serologically confirmed IF were at increased risk for HL (21). After a median incubation time of 4.1 years, postinfectious mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive HL developed with a four times greater risk than normal, but there was no increased risk for EBV– HL after IM (21). Whether IF occurs

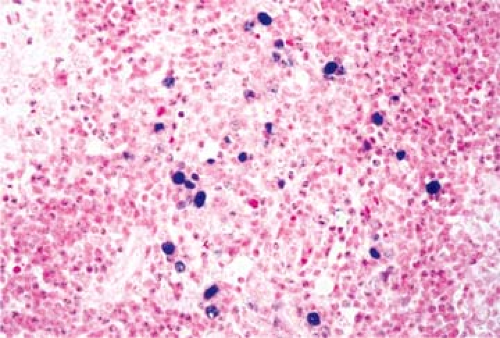

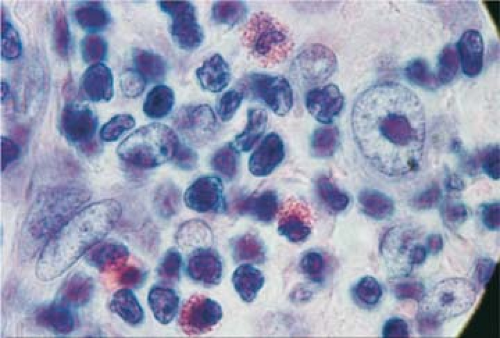

after EBV infection depends on various factors, including some genetic markers. A recent study showed that the presence of certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 alleles correlated with the incidence and severity of IM and that the same HLA alleles were risk factors for EBV-associated HL (22). These findings support the epidemiologic evidence that a history of IM may predispose to HL. Southern blot hybridization with a DNA probe detected monoclonal EBV DNA in 20% of 16 HL biopsy specimens (23). In situ hybridization applied to the same cases showed the EBV nucleic acid to be localized to the Reed-Sternberg (R-S) cells. These findings were confirmed by a large study of 198 HL, 151 NHL, and 34 nonmalignant lymph nodes; by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), EBV-specific DNA sequences were detected in 58% of HL cases (24). The EBV+ cells were monoclonal, suggesting that the EBV infection had occurred before the clonal cell proliferation (23). EBV+ R-S cells are found in 40% to 50% of cases by in situ hybridization with the EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) probe (25) (Fig. 57.1). By in situ hybridization, EBERs were detected in R-S cells in 33%, 53.5%, and 61.6% of cases in three different studies (26,27,28). The differences may be related to geographic location or population variances; however, all studies noted the highest prevalence of the virus in the mixed cellularity (MC) histologic type, the higher clinical stages, and in patients of older age (26,29).

after EBV infection depends on various factors, including some genetic markers. A recent study showed that the presence of certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 alleles correlated with the incidence and severity of IM and that the same HLA alleles were risk factors for EBV-associated HL (22). These findings support the epidemiologic evidence that a history of IM may predispose to HL. Southern blot hybridization with a DNA probe detected monoclonal EBV DNA in 20% of 16 HL biopsy specimens (23). In situ hybridization applied to the same cases showed the EBV nucleic acid to be localized to the Reed-Sternberg (R-S) cells. These findings were confirmed by a large study of 198 HL, 151 NHL, and 34 nonmalignant lymph nodes; by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), EBV-specific DNA sequences were detected in 58% of HL cases (24). The EBV+ cells were monoclonal, suggesting that the EBV infection had occurred before the clonal cell proliferation (23). EBV+ R-S cells are found in 40% to 50% of cases by in situ hybridization with the EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) probe (25) (Fig. 57.1). By in situ hybridization, EBERs were detected in R-S cells in 33%, 53.5%, and 61.6% of cases in three different studies (26,27,28). The differences may be related to geographic location or population variances; however, all studies noted the highest prevalence of the virus in the mixed cellularity (MC) histologic type, the higher clinical stages, and in patients of older age (26,29).

In HIV-infected patients, up to 100% of cases are EBV+ (30). EBV-encoded RNA is identified in the R-S cells of 97% to 100% of HL cases in HIV-infected patients as compared to 30% to 57% in HL of immunocompetent HIV- patients (31,32,33). Latent membrane protein (LMP)-1 is expressed in all HIV infected patients with HL, suggesting an etiologic role for EBV (31) (Fig. 56.22). However, EBV alone may not provide the answer to the cause of HL because in numerous typical cases the same techniques were unable to demonstrate the presence of EBV, and in at least one study, the number of EBV+ cases of HL was not higher than the number of EBV+ cases of benign hyperplastic lymphadenopathies (34).

Classification

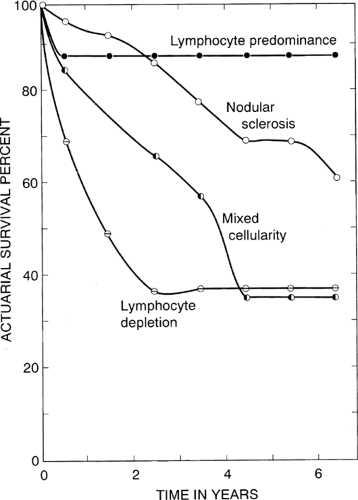

In contrast to malignant neoplasms in general and lymphomas in particular, which are characteristically composed of clonal monomorphic populations of cells, HL presents as a mixture of different cells assembled in a variety of histologic patterns. Also unlike any other neoplasm, HL comprises a minority of neoplastic cells, the R-S cells and their variants, and a majority of reactive inflammatory cells, which form the bulk of the tumor. These include lymphocytes of various kinds, plasma cells, polymorphonuclear neutrophils and eosinophils, histiocytes, and fibroblasts. Attempts were made at various times to identify recognizable histologic patterns among the admixture of cells that constitute HL. An early classification by Jackson and Parker in 1944 (35) divided HL into three subtypes—paragranuloma, granuloma, and sarcoma—a nomenclature suggesting that HL begins as a benign inflammatory condition and eventually evolves into a malignant tumor (Table 57.1). Because the vast majority of cases belonged to the granuloma category, this classification was of limited practical use. In 1966, Lukes and Butler (36) introduced a new classification comprising six subtypes; shortly afterward, at the Rye conference, this was simplified to four subtypes (Table 57.1). This classification was widely accepted by pathologists and clinicians because it correlated well with survival (Fig. 57.2), and it remained the dominant classification for the next 30 years. With the introduction of immunophenotyping, it became apparent that the type of HL designated “lymphocyte predominant” is different from the classically described forms and may even represent a different clinicopathologic entity. This belief was expressed at an international conference held in 1994 on the subject (37) and subsequently defined in the revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms (REAL) (38). With further modifications, included in the presently accepted World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphomas (39), HL is divided into two major entities, lymphocyte-predominant and classical, with the latter further subtyped (Table 57.2). Although both remain under the general heading of HL, we are discussing the two entities in separate chapters to emphasize their multiple differential features (Chapters 57 and 58).

TABLE 57.1 CLASSIFICATIONS OF HODGKIN LYMPHOMA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Pathogenesis

The malignant cells in HL classical type (cHL) are the R-S cells and their mononuclear variant, the Hodgkin cells (H cells). The H/R-S cells arise from the germinal center cells or the immediate post germinal cells. These cells lack detectable immunoglobulin and B-cell antigen receptors (40,41,42,43). Understanding the histogenesis and function of H/R-S cells was much advanced by the PCR analysis of single cells isolated by microdissection (40,41). Thus it was determined that the H/R-S cells have immunoglobulin gene rearrangements with somatic mutations as they originate from the B cells of the germinal center. The B-cell differentiation fails, including the crippling of immunoglobulin gene mutations, the methylation of B-cell differentiation genes, and the expression of B-cell repressors (40,41,42,43,44). The B-cell identity of H/R-S cells is disturbed not only at the immunoglobulin (Ig) expression level, but also at the transcription level by the inactivation of the Ig promoter (42,43). Normally, B cells that have lost the capacity to express Igs undergo apoptosis, however the H/R-S cells are able to block the apoptotic pathway by developing antiapoptotic mechanisms not yet clearly understood or are rescued by EBV infection (39,43).

TABLE 57.2 HODGKIN LYMPHOMA: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) CLASSIFICATION | |

|---|---|

|

Unlike any other neoplasm, the tumor in cHL is made predominantly of the non-neoplastic H/R-S cells rather than the neoplastic H/R-S cells, which often constitute no more than l% to 3% of the entire mass (45). The reactive cells in cHL include lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and fibroblasts. This abnormal immune response to the H/R-S cells is triggered by the production of a large amount and variety of cytokines by the neoplastic cells. Cytokines are low-molecular-weight proteins with a wide variety of functions, including the modulation of immune response, inflammation, and hematopoiesis (46). These molecules are very potent, able of acting in nanomolar concentrations. Most cases of classical HL comprise the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, a member of the tumor necrosis family receptor (TNFR), and the overproduction of helper T-cell type 2 (Th2) cytokines and chemokines such as interleukin (IL)-13, IL-5, and eotaxin (46). CD4+ T-cell lymphocytes are the most abundant cell type in cHL, clustering around the R-S cells (47). Prominent eosinophilia is a characteristic feature of the cHL cellular infiltrate. The eosinophiles are attracted by eotaxin, a chemokine strongly expressed by the fibroblasts of cHL (48), while in turn they are the major source of the fibrosis-promoting cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF-β), which results in the characteristic NL variant of cHL (49). The relationship of tissue eosinophilia with the course of the disease has been controversial. Although some studies indicated a worse prognosis in cHL with prominent eosinophiles (50,51,52), others showed a better overall survival (52). Cytokines and chemokines abundantly produced by both the H/R-S cells and by the reactive infiltrative cells also have important systemic effects including the maintenance of impaired immunologic reactions and important B-type clinical symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss (53).

The localization and spread of HL were long considered to be random and therefore unpredictable. Lymphomas, including HLs, were considered to arise multifocally within the reticuloendothelial system, so that the term metastasis was rarely used in the context of these tumors, as it is for carcinomas and sarcomas (54). This concept derived mainly from observations of advanced disease in which multiple organs were involved. More recently, with the benefit of early diagnosis and the help of modern staging procedures, it has been recognized that HL may start unifocally and at first involve a single lymph node or a single group of lymph nodes. The involved lymph nodes are enlarged and often firm, particularly in NL, in which bands of fibrosis delineate vague nodular areas (Fig. 57.3).

Even within a lymph node, the involvement may be focal, and diseased areas may contrast with uninvolved areas of normal parenchyma (19,55,56) (Fig. 57.4). To avoid missing foci of HL, particularly in lymph nodes that are not grossly enlarged, the whole lymph node should be processed and multiple, preferably semiserial sections examined. The initial foci of HL are usually situated in the interfollicular areas of the cortex (the T-cell zone) without apparent relation to sinuses or capillaries.

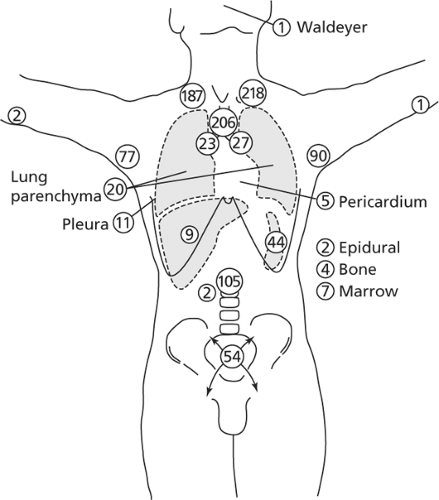

Hodgkin lymphoma spreads mostly by contiguity, from one chain of lymph nodes to another, as demonstrated by the mapping studies of Kaplan (57).

The cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes are most frequently involved, particularly in cases with limited disease (stages I and II) (Fig. 57.5). Abdominal lymph nodes usually are not affected unless the cervical or mediastinal lymph nodes are involved (56,57). From the axillary lymph nodes, HL spreads to

infraclavicular, supraclavicular, and low cervical lymph nodes of the same side and not to the opposite side.

infraclavicular, supraclavicular, and low cervical lymph nodes of the same side and not to the opposite side.

Figure 57.3. Axillary lymph node with nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma shows vague nodularity and whitish areas of fibrosis. |

Correlations between anatomic location and histologic type have been noted. Of all the histologic types, NS is most likely to spread by contiguity, whereas noncontiguous dissemination, when it occurs, is more than twice as frequent in MC and lymphocyte depletion (LD) types (12). Hodgkin lymphoma in the mediastinal lymph nodes is usually of the NS type, which in stage I is 15 times more common in the mediastinum than all other histologic types combined, according to the original study by Lukes and Butler (36) and confirmed by others (12,13). Mixed cellularity and LD types are seldom restricted to a single site or region (57) and are more likely to involve extralymphatic organs and tissues (10). Involvement of the left supraclavicular nodes is often followed by abdominal paraaortic node involvement, whereas involvement of the right supraclavicular nodes tends to be associated with mediastinal adenopathy. Paraaortic lymph node involvement usually precedes involvement of the spleen, which in turn is followed by liver or bone marrow involvement, or both (Fig. 57.6).

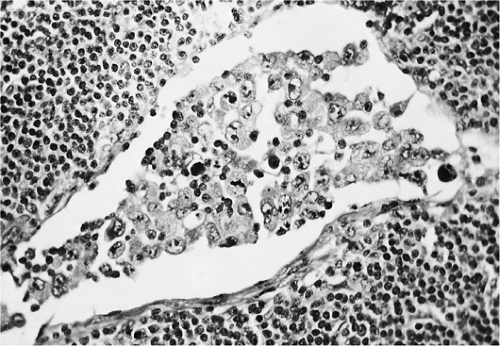

In about 10% of cases, the pattern of contiguous lymphatic spread is not evident (57). The involvement of noncontiguous lymph nodes and the dissemination of HL to bone marrow, spleen, and liver suggest blood vessel invasion, which is estimated to occur in more than 20% of cases (58) (Fig. 57.7). Rappaport and colleagues demonstrated invasion of veins in 6% to 14% of diagnostic lymph node biopsy specimens (58). Silver staining of elastic fibers may reveal the presence of vascular invasion, an aggravating factor that indicates extensive disease and the need for systemic rather than regional therapy (59,60). Although not restricted to the LD type, the invasion of

blood vessels is more frequently associated with this histologic form (60).

blood vessels is more frequently associated with this histologic form (60).

Figure 57.4. Cervical lymph node partially involved by Hodgkin lymphoma. Microscopically, the lesion is restricted to the upper pole, which grossly shows enlargement and discoloration. |

The consistency of histologic types in the presence of multiple localizations and between nonsynchronous lesions has been debated. It is generally believed that simultaneous lesions tend to be of similar histologic type (12,61), whereas during the natural course of the disease, a transition from less malignant to more malignant histologic types commonly occurs (61,62).

The clinical stages of Hodgkin disease are currently evaluated according to the Ann Arbor classification as modified by the Cotswolds Conference in 1989 (63,64) (Table 57.3). The staging procedure as originally formulated required exhaustive surgical and radiologic investigations, including laparotomy, lymph node biopsies, splenectomy, liver and bone marrow biopsies, computed tomography, and gallium scanning. Because involvement can be focal, spleens and lymph nodes removed for staging must be sectioned at 3- to 5-mm intervals and carefully examined. Currently, surgery and lymphangiography are no longer used to stage HL because of potential infectious complications in these immune-deficient patients. Advanced radiologic techniques and successful treatments for all stages have made exhaustive staging unnecessary. When the histologic types of HL are correlated with clinical stages, LP is strongly associated with clinical stages I and II, NS predominantly with stage II, and LD primarily with clinical stages III and IV (13). Mixed cellularity is seen in all clinical stages without any strong associations. Thus, the histologic subtypes may help predict the stage, as in a reported series of 900 staged cases, in which the number of cases with early-stage disease was highest in the patients with LP and decreased progressively from NS to MC to LD (9). Male sex and advanced age were associated with advanced stage and unfavorable histologic type. Massive involvement of lymph nodes and viscera, which were common before modern combined treatment (Fig. 57.6), are rarely seen at present.

TABLE 57.3 ANN ARBOR STAGING CLASSIFICATION FOR HODGKIN DISEASE (AS MODIFIED AT COTSWOLDS) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Syndrome

Most patients with HL first seek medical attention for enlarged lymph nodes (57). They are not usually painful or tender and so are noticed by chance. The growth of lymph nodes may be rapid or slow, but the rate generally correlates with the intensity of constitutional symptoms. The adoption of the Rye classification, based on the histologic subtypes described by Lukes and Butler (36,65), has made it possible to study large series of cases and establish clinicopathologic correlations. Thus, in a series of 659 patients with HL, the mediastinal lymph nodes were more commonly involved in up to 80% of cases with lesions of NS, whereas abdominal lymph nodes were more often affected by lesions of MC (66). Bulky lesions were seen in 54% of cases (39). The cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes were most commonly involved in all forms of HL, particularly NS. One-fourth of the cases of LP showed inguinal involvement. The tonsils and Waldeyer ring are rarely involved. As in other series, earlier stages (I and II) were more often associated with LP and NS, whereas advanced stages (III and IV) had MC and LD lesions.

Patients with HL show various degrees of immune deficiency. Lymphocytopenia and a functional impairment of T lymphocytes are common and result in an increased susceptibility to some types of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections (67). In HIV-infected patients, HL may occur in unusual sites, and the bone marrow may be involved in the absence of lymph node involvement (68), in contrast to immunocompetent patients in which the bone marrow is affected in only 3% of cases (39).

B-type symptoms include fever (>38°C for 3 days consecutively), night sweats (sometimes considerable as a consequence of nocturnal defervescence), pruritus, anorexia, fatigue, generalized weakness, and weight loss. Their presence and intensity generally correlate with the pathologic stage. In NS, they occur in about 40% if cases (39). Nodular sclerosis is the only type without a male predominance; the male-to-female ratio is 1 (39). The MC type is seen more often in middle-aged patients, 70% males who present in stages II and III. Lymphocyte depletion, the most aggressive form of HL, accounts for less than 5% of cases and affects elderly men, involving subdiaphragmatic lymph nodes and showing at autopsy a high rate of vascular invasion and extranodal spread (39). Mixed cellularity and LD are more common in developing countries and in HIV/AIDS patients (39).

Histopathology

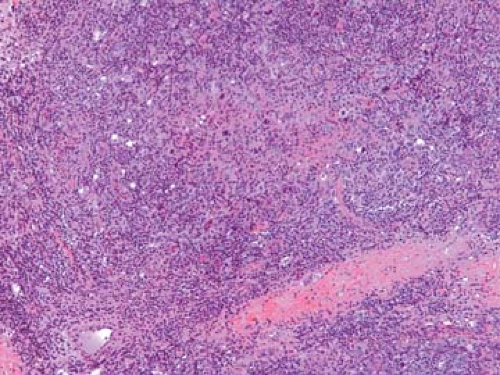

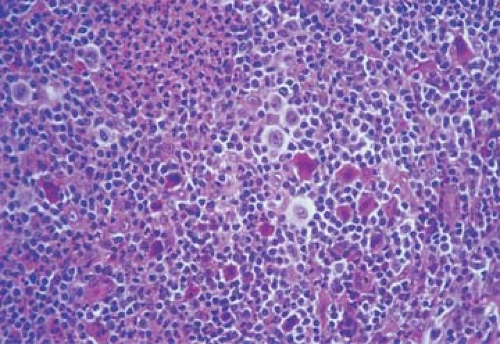

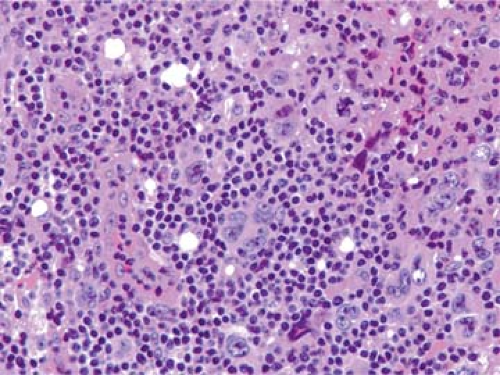

The cell populations of HL are heterogeneous, including neoplastic and non-neoplastic reactive cells. Varying proportions of neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells give rise to multiple histologic patterns (Figs. 57.8,57.9,57.10,57.11).

The Rye classification (Table 57.1), a simplified four-category version of the original six-category classification of

Lukes and Butler (36), was formerly used worldwide and offered clinical relevance and high reproducibility (63). It has been replaced by the new WHO classification of HL; this system separates LP from cHL, which includes all other histologic types (39) (Table 57.2).

Lukes and Butler (36), was formerly used worldwide and offered clinical relevance and high reproducibility (63). It has been replaced by the new WHO classification of HL; this system separates LP from cHL, which includes all other histologic types (39) (Table 57.2).

Figure 57.8. Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular sclerosis, with band of fibrocollagen and mixed-cell population including several large neoplastic cells. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Figure 57.9. Mixed cellular population in Hodgkin lymphoma with various inflammatory cells, Reed-Sternberg cells, lacunar cells, and mummified cells. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Figure 57.10. Hodgkin lymphoma, mixed cellularity, including Reed-Sternberg cells (one in mitosis), Hodgkin cells, mummified cell, and lymphocytes. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Cell Types of Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma

Unlike the NHLs, which comprise a homogeneous population of tumor cells, the HLs are composed of mixed infiltrates of neoplastic and inflammatory cells, the latter forming the vast majority (Figs. 57.8 and 57.9). The R-S cells and their variants may account for 10% to as few as 1% of the entire cell population (45) (Fig. 57.10).

Non-Neoplastic Cells

Non-neoplastic cells are considered to represent an immune cellular reaction to the neoplastic cell component of HL. Their morphologic features are indistinguishable from those of their normal counterparts, and their respective numbers vary in relation to the histologic subtypes of HL. Lymphocytes, which are small with round nuclei and rare mitoses, are the predominant cell type. The majority of lymphocytes are T cells, mostly of CD4+ helper type 2 (Th 2) (68). The ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells is within normal range. Admixed with the lymphocytes are occasional immunoblasts, plasma cells, neutrophils, and particularly eosinophils. The latter is a constant and characteristic component of the NS and MC types (Fig. 57.11). Eosinophils are attracted by eotaxin, a chemokine expressed by the fibroblasts of HL, particularly the NS type (46,48). The number of eosinophils may be very great, and they sometimes form eosinophilic microabscesses. In one case, a 68-year-old man had a peripheral leukocyte count of 120,000/mm3 with 92% eosinophils, which led to an initial diagnosis of eosinophilic leukemia (19). At autopsy in such cases, the lymph nodes and most other organs show infiltrates of MC in which the eosinophils are the predominant cell type. Neutrophils, when present, usually surround the foci of necrosis.

Histiocytes and fibroblasts are commonly noted. Epithelioid cell granulomas are occasionally present in the involved or uninvolved lymph nodes of patients with HL and have been described repeatedly (69,70,71). The incidence of this finding was 9% in a survey of 608 patients (70) and 16.7% in a study of 185 patients (69). The granulomas are randomly distributed in the

nodal parenchyma and comprise epithelioid histiocytes, a few multinucleated giant cells of Langhans or foreign-body type, and scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells. Central necrosis is minimal or lacking, and asteroid bodies are not seen. Some authors have reported longer survival for patients with epithelioid granulomas (70); however, the relation of epithelioid granulomas to HL is not understood. Hodgkin lymphoma with a high content of epithelioid cells is classified with the MC type (71).

nodal parenchyma and comprise epithelioid histiocytes, a few multinucleated giant cells of Langhans or foreign-body type, and scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells. Central necrosis is minimal or lacking, and asteroid bodies are not seen. Some authors have reported longer survival for patients with epithelioid granulomas (70); however, the relation of epithelioid granulomas to HL is not understood. Hodgkin lymphoma with a high content of epithelioid cells is classified with the MC type (71).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree