INTRODUCTION

The rush-hour traffic on the 405 freeway in Los Angeles seemed even worse than usual and Andrew Martin’s thoughts began to drift back to his workday and the big construction deal that he had been working on for a month but was now falling through. Suddenly he began to feel a dull, constant pressure in his chest that travelled down his left arm. He took a few deep breaths, but the pressure seemed to get worse and began to feel like it was suffocating him. He pulled off the freeway and drove to the closest emergency room. As a previously healthy 55-year-old man he infrequently saw a primary care provider and did not take any medications. The emergency department (ED) physician said that it seemed like a panic attack, but that he should be admitted overnight to get some tests in order to “just make sure that this isn’t your heart.” Although that statement made him even more nervous, Mr Martin’s chest pain resolved shortly after arriving at the hospital.

He spent the night under telemetry monitoring in an observation unit located next door to the ED. The next morning a cardiologist stopped by his bed and told him that based on his blood work (two negative troponin tests obtained 8 hours apart) and his normal ECGs, he was not having a heart attack, but that his cholesterol drawn this morning was found to be high. His 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (derived from the Framingham risk calculator)1 was approximately 15%, so the cardiologist recommended that he start on a statin. Mr Martin agreed to take this medication and the cardiologist wrote him a prescription for Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium; Pfizer Inc) 40 mg by mouth, once daily. Mr Martin left the hospital and went straight to his closest pharmacy to fill the prescription. When the pharmacist entered the prescription she told him that this medication will cost him $191 each month. Mr Martin is worried about his cholesterol and the fact that the cardiologist told him that he is at risk of having a real heart attack one day, but he thinks back to his failed construction deal and his tight financial situation. “Never mind for now, I will have to come back another time,” Mr Martin tells the pharmacist, leaving the drug store without his prescription.

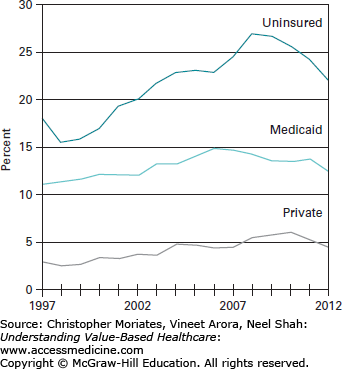

Unfortunately, the out-of-pocket costs of medications have led many patients to forgo recommended treatments. Patients like Mr Martin are often not aware that less costly statins exist and they may feel embarrassed about bringing up an inability to pay for this medication with a healthcare provider. Although the majority of patients report a desire to talk to their doctors about out-of-pocket drug costs, only 15% of patients say they have ever done so.2 The discomfort caused by discussing costs is not only common for patients, but healthcare providers as well. In one study, 79% of physicians wished that they could discuss costs with patients but reported unease with the topic, insufficient time, and doubts about viable solutions.3 These discussions are vital, however, since cost-related medication underuse is prevalent in the United States, particularly among the uninsured (Figure 13-1).4 This chapter will review a number of potential mediators at both the clinician and health system level that can help patients navigate this concerning problem. We should note upfront that evidence suggests the most effective and consistent way to reduce the risk of cost-related nonadherence is to provide patients with any form of prescription drug coverage.5

On the quality side of the value equation, many patients are not benefiting from their prescription plans due to complicated regimens. More than half of all patients above 65 years old take three or more prescription medications.4 While most of these patients likely have appropriate indications for a number of their medications, patients with the same chronic illnesses have highly variable levels of medication complexity.6 The problem is that complex prescription regimens are clearly associated with reduced compliance compared to simple regimens.7

High-value prescribing entails providing the simplest medication regimen that minimizes physical and financial risk to the patient while achieving the best outcome. In other words, decreasing either cost, complexity, or risk of medications can improve value. Ideally, providers should aim to decrease all three simultaneously.

UNDERUSE OF MEDICATIONS DUE TO COST AND COMPLEXITY

Medication nonadherence results in poor disease management and costly complications,8 including increased ED visits, psychiatric admissions, nursing home placements, and decreased overall health status.9-11 Patients are not just failing to fill that prescription for loratadine for their season allergies, but also essential medications such as hypoglycemics, diuretics, bronchodilators, and antipsychotics.3 The data suggest that more than one million adults diagnosed with diabetes may be taking less hypoglycemic medications than prescribed because of cost, and an additional 750,000 people with diabetes may be cutting back on their medications at least once per month.3 Incredibly, these numbers do not even include the patients that are noncompliant for a myriad of other reasons, including medication regimen complexity and other psychosocial factors.

If you see patients in a clinical setting, then you undoubtedly see patients who are not taking their medications as prescribed due to costs. Bearing in mind this overwhelming prevalence of cost-related medication nonadherence, clinicians should consider this as a possible cause whenever a patient “fails” to respond to pharmacotherapy. Instead, clinicians often reply to these “medication failures” by prescribing more medications, ultimately exacerbating the underlying problem of unaffordability. Relying on patients to mention their nonadherence or their financial difficulties will not suffice. About one-third of chronically ill adults who underuse prescription medications due to medication costs never talk with clinicians about this issue.3

Contributing to the problem of medication underuse is the increasing complexity of medication regimens. The medical management for congestive heart failure now includes a cocktail of different drugs consisting of aspirin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), β-blockers, statins, and diuretics. A review of the studies on barriers to medication adherence in the elderly12 found that four studies showed taking more drugs led to worse overall adherence,13-16 and a single study reported the opposite.17 It is not simply about the total pill count: medication regimens can also vary significantly in complexity due to multiple dosage forms, frequency of dosing, and additional usage directions.6 In patients with poorly controlled diabetes, taking diabetic medications more than twice daily led to decreased adherence and worsened blood sugar control (as measured by hemoglobin A1c).18 In another study compliance improved from 59% on a three-time daily regimen to 84% on a once-daily regimen, leading the authors to declare, “Probably the single most important action that healthcare providers can take to improve compliance is to select medications that permit the lowest daily prescribed dose frequency.”7

Medication complexity is a modifiable risk factor to adherence; therefore, efforts should be made to provide patients with the simplest appropriate regimen. Clinicians could consider combination pills that include two or more common medications and doses, which decreases pill burden and may provide better compliance for patients with chronic conditions, such as hypertension.19 Combination pills may be cheaper than the component medication separately. however, this strategy requires caution since some combination pills can be inappropriately expensive. In these instances the trade-off between medication complexity and cost burden will need to be carefully weighed lest you replace one medication adherence problem with another.

Of course, clinicians must also consider whether or not their patient can appropriately understand the medication regimen in the first place. Health literacy is low in many US populations and a lot of patients have limited English proficiency. Dr David Margolius shared a parable about misinterpreted medication instructions in a Los Angeles Times Op-Ed: “The story of ‘once’ is a cautionary tale that—best as I am able to tell from Google—was adapted from a Spanish soap opera. In one version, a doctor prescribes a patient a 30-day supply of a medication. Three days later, the patient returns for a refill. ‘How can this be?’ the doctor wonders. The Spanish-speaking patient responds, ‘I took the pills exactly as the bottle said to: ‘11 daily.’ The doctor scrutinized the pill bottle: ‘Take once daily.’ But ‘once’ read and pronounced ‘ohn-say’ means 11 in Spanish. The patient had taken 11 pills daily, just as the bottle label said—in Spanish. The patient lives in that story, but in other versions he is hospitalized or even dies.”20

It is imperative that providers take into account their patients’ ability to pay for, understand, and comply with their medication regimen, otherwise their efforts to provide thoughtful and effective medical care may be easily undermined.

WHY DO WE SEE LOW-VALUE PRESCRIBING?

The tools and strategies we highlight in this chapter are designed to help clinicians and their patients address the challenges presented by the costs and complexity of therapeutic options. However, there are several barriers to high-value prescribing that will require systems-level solutions, beyond the individual patient-clinician encounter. Chapter 3 reviewed the challenge of price transparency and Chapter 12 discussed some of the emerging tools to help patients better understand the cost and quality of care they are receiving. Although medication costs are often easier to discern prior to purchase than diagnostic tests and other health services, prices may vary in equally frustrating and arbitrary ways. For example, oral contraceptive pills, one of the most frequently prescribed medications for women of reproductive age, can vary by an order of magnitude in monthly cost to the patient, depending on the coverage plan, formulation, and pharmacy that is selected.21 This variation in pricing makes it challenging for both patients and care providers to track lower cost options and has left a gap in medical education, with many clinicians feeling unprepared to deal with medication costs.3

Our fee-for-service reimbursement system also presents a notable challenge to high-value prescribing (see Chapter 15). This is particularly evident in cases where both medical and surgical management may be appropriate. Because performing procedures generates more reimbursement than prescribing medications, opportunities to use a high-value medication may be overlooked or dismissed. The evidence for this exists at the systems level—as we point out in Chapter 7, many procedures in the United States are performed at variable rates in different regions, sometimes varying more than 20-fold, without an apparent medical explanation or benefit.22 An all too common example is joint arthritis, which depending on the patient’s individual case and goals of care might be managed conservatively with medication and physical therapy or surgically with an elective knee, shoulder, or hip replacement. Recent data suggest that the skewed incentives to operate may be leading to unnecessary surgery in many parts of the country, where medical therapy may have been more appropriate.23

Sometimes an expensive medication can be worth it if it helps avoid an even more expensive, risky, or otherwise undesirable surgery. As an extreme example, medical hormonal therapy costs significantly more than bilateral orchiectomy (removal of testes) for men with prostate cancer. Although both hormonal therapy and castration are reasonable approaches, the very expensive hormonal therapy appears worth it and creates positive value for men with prostate cancer by enabling them to avoid a highly undesirable surgery.24

The influence of the pharmaceutical industry on prescribing practices has recently drawn increased scrutiny within academic medicine. Through a combination of lobbying efforts and targeted marketing, the industry as a whole spends more than one-third of all sales revenue (approximately $100 billion) on promoting the use of their products.25 While advertising in itself may not be necessarily problematic, tensions arise when industry incentives to maximize shareholder profits are misaligned with the patient and caregiver incentives to deliver high-value care.

A 2003 survey of third-year medical students revealed that over 93% of them reported accepting food from a pharmaceutical company. At that time, resident physicians also commonly interacted with pharmaceutical companies, which altered their prescribing behaviors.26 Even exposure to small pharmaceutical promotional items subtly influences medical students’ attitudes toward the advertised product.27 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) both recommended drastically curtailing commercial involvement in medical education.28-30 In response, numerous medical schools, residency programs, and academic medical centers have limited industry access to medical training, although this ban is far from complete.31, 32 The American Medical Student Association (AMSA) has created a “PharmFree” scorecard that publically compares conflict of interest policies across academic medical centers (available at http://www.amsascorecard.org), which has also helped catalyze these policies. Recent studies provide encouraging evidence that these medical school policies are associated with changing student attitudes toward marketing,27 and lead to more conservative future prescribing practices.33 Despite these inroads in the undergraduate and postgraduate educational arenas, the world of continuing medical education (CME) remains substantially sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. This seems less likely to change significantly anytime soon because the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) has considered but rejected ending commercial support,34 which in 2011 equaled approximately $736 million.35 Of note, this does represent a dramatic decrease from the peak of $1.2 billion in CME commercial support, back in 2006.34, 35

Outside of education, in the “real world” of private practice physician offices and community hospitals, the lunchtime visits from pharmaceutical representatives and the invited dinner lectures are often a daily occurrence. Payers have a unique ability to drastically influence this situation by creating a policy that would ban their providers from these relationships. One move in that direction is the new “Physician Payments Sunshine Act,” which requires public reporting of payments to physicians and teaching hospitals from pharmaceutical and medical device companies. This law includes meals, honoraria, travel expenses, and grants. The data started being published on a public website in 2014.36 Perhaps this will help prove the adage, “sunshine is the best disinfectant.”

SCREENING PATIENTS FOR FINANCIAL BURDEN OF MEDICATIONS

As already discussed, patients are usually uncomfortable initiating conversations about medication costs with their physicians. There are a number of reasons for this discomfort, but patients say that an important contributor is the perception that their clinicians are unwilling or unable to help them with this problem.3 Perhaps this is because providers have never asked them about their medication adherence or their financial situations. Eighty-five percent of patients reported they have never discussed out-of-pocket costs with their physicians, and only 16% of patients believe that their physician was aware of the magnitude of their out-of-pocket costs.2 There is little wonder as to why patients think that this is not a priority to their providers. Maybe the reality is that with the many challenges and competing urgencies that clinicians face, it frankly is not. But it absolutely should be. It is central to the care for many patients. And patients who are not asked by their providers about the problem of medication costs have a more global, negative perception regarding their clinicians’ overall interest and potential ability to assist them.3

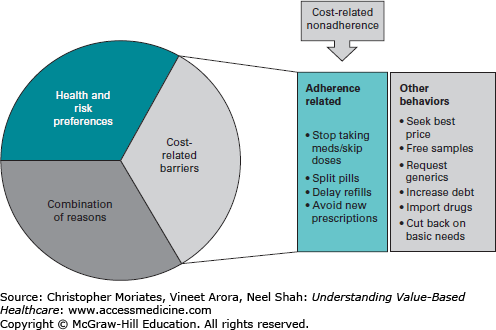

At least equally concerning, patients adopt other strategies—in addition to underuse of medications—to cope with the burden of high medication costs (Figure 13-2). These include cutting back on necessities such as food or heat to pay for medications. Many take on increased debt.37 This strain on household budgets can cause further erosion of personal health. According to one study, almost a quarter of Medicare patients without prescription drug coverage had cut back on food or clothing because of medication costs.38 As the Haitian proverb goes, we may be “washing our hands and then drying them in the dirt” by prescribing medications that aim to help with medical conditions but that are actually compelling older patients with chronic conditions to forgo necessities, eat less healthily, and increase their debt burden.

Figure 13-2

Relationship between medication nonadherence and cost-related behaviors. (Reproduced from Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):864-871. With kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media.)

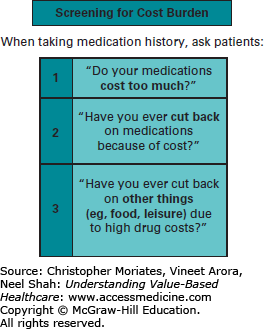

The first step for clinicians to address this common problem is to ask simple questions to screen patients for financial burdens associated with their medications. We propose three specific questions to ask patients while taking a medical history (Figure 13-3)39:

Do your medications cost too much?

Have you ever cut back on medications because of cost?

Have you ever cut back on other things (eg, food, leisure) due to high drug costs?

Figure 13-3

Proposed method for screening patients for cost burden related to medications. (Rupali Kumar, Neel Shah, Andy Levy, Mark Saathoff, Jeanne Farnan, Vineet Arora. GOT MeDS: designing and piloting an interactive module for trainees on reducing drug costs. Society of General Internal Medicine Presentation, April 2013.)

Making such screening routine, much like is done with advanced directives, could help alleviate the patient or physician discomfort with this topic.40

This paradigm of screening patients for medication-related financial harm applies to hospitalized patients as well. In one survey of hospitalized adults, 23% reported cost-related underuse in the year prior to admission.41 Yet, few patients (16%) who were prescribed medications at discharge knew how much they would pay at the pharmacy, and almost none of them had spoken to their inpatient (4%) or outpatient (2%) providers about the cost of newly prescribed drugs.41 Any benefit from a hospitalization could be too easily unraveled by careless discharge prescriptions that a patient cannot appropriately fill. Not taking medication costs into account can easily lead to preventable and unnecessarily costly readmissions. In one case recently presented at an M&M (Mortality and Morbidity) conference, a patient was readmitted to the hospital for anticoagulation treatment of his cancer-related deep vein thrombosis after he was unable to afford the out-of-pocket costs of Enoxaparin injections. His previous inpatient medical team had neither taken this possibility into consideration nor tried to obtain a prior authorization.

TOOLS FOR DETERMINING MEDICATION COSTS

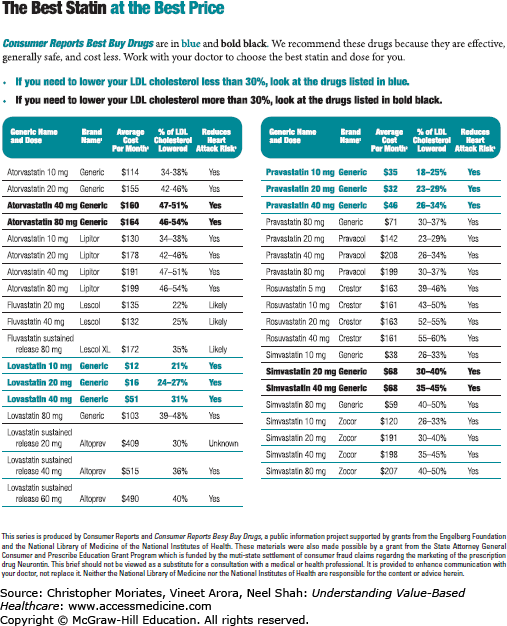

Healthcare providers require clear information regarding the relative efficacy and price of medications. Fortunately, there are many tools and resources available for both physicians and patients. These include websites such as www.consumerreports.org, mobile applications like Epocrates and Lowestmed.com, and drug store discount generic drug lists (as discussed below).

Consumer Reports has created a number of “Best Buy Drug Reports” listed by condition and by specific drug name (Figure 13-4).42 Their statin list points out that, “Statins can vary widely in cost—from as little as $12 per month (and even less if your drug is available on a drug store’s discount generic list) to more than $500. Most people who take them must continue to do so for years—perhaps for the rest of their life—so the cost can be an important factor to consider.”43

1“Generic” indicates a drug sold by generic name.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree