INTRODUCTION

James Anderson, a 45-year-old accountant, regularly plays basketball and has always been healthy and active. For the past 2 weeks though he has not been able to shoot hoops due to low back pain. Two Saturdays ago, he cleaned out his garage and was moving around heavy boxes. He awoke the next morning feeling an aching pain in his low back, with an occasional intermittent sharp pain when he moved in certain positions. The discomfort seemed to be worse with bending and standing, and after lying down for long periods. After 2 weeks of using ice and heat packs, and Tylenol, with only temporary improvements, he decided to go see his doctor.

His doctor asked him a number of questions about the pain, ensuring that he did not have any bowel or bladder incontinence, fevers, weakness or numbness in his legs, or other concerning neurologic symptoms. He performed a full examination including a neurologic exam, which was completely normal except for some limited back mobility due to discomfort and some tenderness surrounding the lumbar spine region.

The physician explained to Mr Anderson that his back pain was almost assuredly “benign” and would get better slowly over about 4 to 6 weeks, but then suggested that he would order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of his back, “just to be sure.”

Approximately one-quarter of American adults have had low back pain that lasted at least 1 day in the last 3 months,1 leading low back pain to be the fifth most common outpatient complaint.2 In the United States, we spend a lot of money on back pain. The direct expenditures annually are similar to that for diabetes and for cancer.2,3 And yet for low back pain we are not actually making people much better. Between 1997 and 2005 the United States had rapidly increasing medical expenditures for low back pain, but there were no measurable improvements in outcomes for patients, including self-assessed health status, functional disability, work limitations, or social functioning.2.

Expensive imaging tests are a major contributor to these excessive healthcare costs.4 The problem is that abnormalities on imaging are as common in individuals with and without back pain. More than 57% of asymptomatic people over 60 years have abnormalities on lumbar MRIs.5 Clinical guidelines published by the American College of Physicians (ACP) recommend against obtaining imaging in any patient with low back pain without “red flag” symptoms—specific symptoms that are considered concerning for certain possible underlying diseases—within 4 to 6 weeks of onset, since imaging of the lumbar spine before 6 weeks does not improve outcomes but does increase costs.4,6 The American College of Radiology (ACR) agrees that imaging is frequently overused in the evaluation of low back pain and notes that most patients return to normal activity within one month regardless of imaging.7

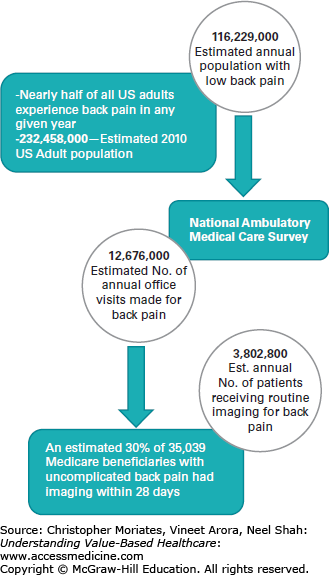

Despite a mountain of evidence and clear guidelines, about 40% of family practice and 13% of internal medicine physicians reported ordering routine diagnostic imaging for acute low back pain.8 Dr. Shubha Srinivas and colleagues from the University of Connecticut estimate that more than 3.8 million Americans receive routine imaging for low back pain each year (Figure 4-1).9 This places patients at risk of excessive radiation (in the case of x-rays and computed tomography [CT] scans), costs, and substantial cascading downstream effects.10 In addition, unnecessary imaging may lead to substantial out-of-pocket costs, particularly for patients like Mr Anderson who have a high-deductible insurance plan (see Chapter 2) and therefore are responsible for up to the first few thousand dollars in costs. The further downstream effects of back imaging include undue worry, perceptions of worsened back pain and/or lessened overall health status,11 and even unhelpful spine operations.12,13

Routine imaging for low back pain is just one of countless examples of a costly test that does not provide higher quality care for patients.

WHAT IS “VALUE”

The meaning of “value” in healthcare—very roughly defined as the output of healthcare per unit of cost—may differ widely whether considered from the perspective of the patient, provider, or payer.14

“Value in healthcare depends on who is looking, where they look, and what they expect to see,” Harvard cardiologist and journalist Dr Lisa Rosenbaum has suggested.14 For clinicians, value may mean decreasing overuse and inefficiency, while improving compliance with evidence-based care. But for patients, creating value may signify enriching the patient experience and concentrating on patient-centered outcomes.14

These differing perspectives have created a gap that must be investigated and bridged. However, at the most basic level there is general agreement that value should include cost, outcomes (or quality of care), and patient experience. And it is clear that currently there is substantial room for improvement in all of these areas (see Chapter 1).

We believe that clinicians should begin to consider the value of a healthcare intervention similarly to how their patients think about it. Many others have also warned that value in healthcare should consistently be defined by what actually matters to patients.14-16 This is because when considered from the perspective of the patient, value has the power to unite the interests of all players in the healthcare system.15 So, how do patients weigh the healthcare “value equation”?

In most instances the quality (“the numerator” of the value equation) of the recommended test/procedure/medication may be summarized as simply “what will this do for me?” Notably missing from the brief conversation above with Mr Anderson was any indication of what the potential benefits of undergoing the MRI would be for him. Patients should understand the potential benefit to them personally of recommended tests, procedures, or medications. The growing interest in measuring and addressing clearly defined patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) is discussed in Chapter 12.

Whether or not clinicians explicitly address benefits, one must understand that patients will automatically weigh their perceived benefit with their own values, history, and context surrounding medical care. A patient whose father died at the age of 57 from prostate cancer that was metastatic to the spine will likely view back pain very differently from someone like Mr Anderson who has never directly known anybody with cancerous bone lesions causing pain.

Clear communication between medical staff and patients is vitally important, and has been shown to improve appropriate testing by reducing underuse, overuse, and misuse.17 In a randomized clinical trial, women who were fully counseled about testing options, had undergone exercises to clarify their personal values, and had financial barriers removed were measurably better informed and chose to undergo prenatal genetic testing less frequently than other women.18

As for costs (“the denominator” of the value equation), this may prove to be even more nuanced for patients and clinicians. Although weighing quality with cost is how almost all other consumer decisions are made, healthcare has traditionally not been determined this way. As we discussed in Chapter 3, this is at least partially because true healthcare costs and quality information have broadly been hidden from patients and physicians, contributing to both groups’ difficulties in making rational decisions about healthcare. Furthermore, most patients are shielded from the full cost of medical purchasing decisions by their health insurance (see Chapters 2 and 3).

Some patients may not necessarily be concerned about their healthcare resource consumption. In one study, interviews with privately insured patients revealed that few of them understood terms such as “medical evidence” or “quality guidelines,” and most believed that more care automatically meant higher-quality care.19 The idea that receiving less care could actually be safer and be of higher-quality seemed counterintuitive. “I don’t see how extra care can be harmful to your health,” one participant said.19 “Care would only benefit you.” In fact, some patients may explicitly equate more costly care with better care. Despite a vocal contingent of patients who express this view, it is quite obvious that in many instances patients do care a lot about their healthcare costs. Indeed, healthcare costs lead many patients to postpone or skip needed care,20 and it is increasingly clear that the financial harms alone can be substantial for patients.21-23 Since value depends on “what matters to patients,” and patients are generally concerned about the monetary costs of medical care, we believe that financial costs should be included in modern clinician risk/benefit calculations.21

The costs considered in the value equation should not only focus on financial costs but also include other costs potentially incurred by patients, such as possible physical harms, downstream effects, and anxiety. In the case of routine back imaging, this may include out-of-pocket costs, the logistics of missing a day of work, the story one heard from a friend about the claustrophobia of lying still in the MRI tube, and the anxiety of worrying about being “unwell.”11 These additional costs to patients may be summed in terms of the overall experience of care. Even an objectively improved outcome may not be worthwhile to a patient if it entails significant physical or psychological suffering.24

To be clear, this does not mean that patients in the right age and risk group should not undergo testing, such as back imaging, when warranted, but rather that clinicians should understand the personalized value equation that patients may be, perhaps even subconsciously, calculating. When recognized, the healthcare provider can help patients more explicitly navigate this calculus. Actively engaging patients in their healthcare has been shown to be associated with better health outcomes and care experiences,25 and possibly even lower costs.26

Most clinicians are currently unaware of the cost of routinely ordered tests,27 but to explain the potential options and their fiscal implications to patients, health professionals should take responsibility for knowing the financial ramifications of the care they are recommending.21 This does not always require knowing the exact dollars-and-cents costs, but clinicians can utilize resources so to at least provide estimates within an order of magnitude. For instance, the clinician should be able to, at the very least, point Mr Anderson to a resource to check with his insurance about how much the MRI would cost him out-of-pocket (see Chapter 12 for some examples of emerging tools for cost transparency). There are also multiple emerging tools, which are discussed in Chapter 13, for clinicians to evaluate and possibly decrease out-of-pocket costs of prescription medications for their patients.

Of course, one of the best ways to deflate medical bills is to avoid interventions that do not make patients healthier—such as inappropriate back imaging. Avoiding unnecessary medical tests, procedures, and treatments is the easiest way to simultaneously improve quality of care, safety, and patient experience, and decrease costs.28

Although “value” has emerged as a catchall term to encapsulate the quality, experience, and costs of care, it often gets conflated into being about costs alone. In the past, value improvement was met with skepticism by both physicians and patients, who feared it was being used simply as a euphemism for blanket cost controls.29 Even today the terminology is confusing. Some may conjure up images of McDonald’s “value meals” or the local diner’s “blue plate special”—not really an appealing metaphor for a healthcare service. However, to be clear, we do not use value here as a code word for cost reduction.

The distinction between cost and value is critical (Table 4-1). Certain high-cost interventions are extremely beneficial in the right setting. An MRI scan provides excellent value for the evaluation of a suspected epidural abscess (a collection of infected pus around the spinal cord), but that same study is considered low-value when used for routine evaluation of common low back pain, since it does not improve outcomes. On the other hand, there are other interventions that are typically low-value, regardless of cost, because they do not improve patient outcomes under almost any circumstances, and even may cause harm.

Cost, benefit, and value of medical interventions

| Cost | Net Benefit | Value | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | High | Usually high-value, but depends on the situation and the relationship of costs and benefits | High-value: MRI for epidural abscess |

| Low | Low | Low-value: Routine MRI for low back pain | |

| Low | High | High | High-value: Universal HIV screening |

| Low | Usually low-value, but depends on the situation and the relationship of costs and benefits | Low-value: Preoperative testing prior to low-risk surgery like cataract surgery |

Consider the routine, rather than clinically indicated, replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVs). Most hospitals require that PIVs be replaced in inpatients every 72 to 96 hours. This has been shown to be a wasteful practice with no difference in rates of infection or phlebitis (inflammation of the blood vessel) for patients compared to replacing PIVs only when they have failed or show evidence of emerging infection.30-32 Even though the individual cost saving from saving plastic PIVs is rather minimal, this practice could likely be completely eliminated without negatively affecting patients. In fact, decreasing needle sticks would be very welcomed by patients and is likely to improve their care experience. Thus, even low-cost interventions may be of low-value and should be targeted for elimination. This means that simply concentrating on return on investment is likely an inadequate way to assess the success of healthcare strategies aimed at improving value for patients.33 Therefore, although cost is part of the value calculation, it does not solely define it.

Simply put, value is increased either by improving the quality of care delivered to patients at similar costs, or by reducing the total costs involved in a patient’s care while maintaining quality. The improvement of healthcare value, when appropriately applied, stands to benefit patients, clinicians, payers, and medical systems.

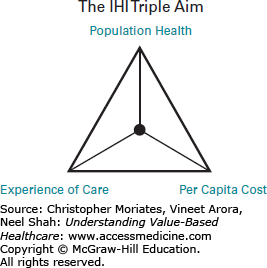

In order to assess whether the delivery of a healthcare service is high-value, it is useful to couch value improvement efforts within the shared goals of the health system as a whole. In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) proposed a framework for optimizing health system performance known as the “triple aim” (Figure 4-2)28:

Improve the experience of care

Improve the health of populations

Reduce per capita costs of healthcare

These aims are interdependent and require a balanced approach.28 If not taken together, some health systems may improve quality while generating exorbitant costs. Alternatively, haphazard application of these aims could lead to decreased costs but at the detriment of the patient experience or quality of care. Therefore, it is vital that these three goals are pursued equally and simultaneously. If a space shuttle with excellent insulation design exploded due to faulty fuel mechanics, nobody at NASA would be celebrating the good insulation; they would be lamenting the overall failure of the mission.

The triple aim has been broadly adopted as an aspiration of many health system improvement efforts but it can be challenging to implement. With many moving parts that must be tackled in tandem, it requires the dedication of frontline clinicians as well as health systems leaders. It also requires a way of defining, measuring, and prioritizing the components of the value equation at the healthcare system level.

The triple aim goals imply a focus on the bottom-line results achieved—not just the volume of services delivered or the number of patients that are cared for.15 Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter has helped popularize a tiered “Outcomes Measures Hierarchy” with implications for both healthcare quality and patient experience15:

Tier 1: Health status achieved (survival; degree of health recovery)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree