Hernia Repair

Maya N. Clark-Cutaia

A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a peritoneum-lined sac through the musculoaponeurotic covering of the abdomen. The word hernia is a Latin term that means “rupture” of a portion of a structure. Descriptions of hernia reduction date back to Hammurabi of Babylon and the Egyptian papyrus. Weakness of the abdominal wall, congenital or acquired, results in the inability to contain the visceral contents of the abdominal cavity within their normal confines. This defect occurs frequently; hernia repair is the most common operation in general surgery. About 10% of the population develops some type of hernia during their lifetime, with more than 800,000 hernia repairs performed each year. About 50% are for indirect inguinal hernias, with a male-to-female ratio of 7:1, and 25% are for direct inguinal hernias. Fourteen percent are umbilical (female-to-male ratio, 1.7:1), 5% are femoral (female-to-male ratio, 1.8:1), and 10% are incisional (female-to-male ratio, 2:1). With aging, the prevalence of all varieties of hernias increases (Erickson, 2011).

Hernias have a tremendous economic significance in the United States. The number of workdays lost is substantial. The increase in ambulatory surgery for hernia repair is one of many attempts to provide cost-effective healthcare that also leads to patient satisfaction.

A hernia can occur in several places in the abdominal wall, with protrusion of a portion of the parietal peritoneum and often a part of the intestine. The weak places or intervals in the abdominal aponeurosis are: (1) the inguinal canals, (2) the femoral rings, and (3) the umbilicus. Any number of conditions causing increased pressure within the abdomen can contribute to the formation of a hernia. Contributing factors to hernia formation include age, gender, previous surgery, obesity, nutritional status, occupation, and pulmonary and cardiac disease. Loss of tissue turgor occurs with aging and in chronic debilitating diseases, perhaps impairing collagen metabolism and weakening fibroconnective tissue in the groin. Successful hernia repair is measured by incidence of complications, total costs, ability to return to work or normal activities (Tolver et al, 2012) and rate of recurrence (Research Highlight).

Surgical Anatomy

A hernia is a sac lined by peritoneum that protrudes through a defect in the layers of the abdominal wall. Generally, a hernia mass is composed of covering tissues, a peritoneal sac, and any contained viscera. Hernias may be acquired or congenital.

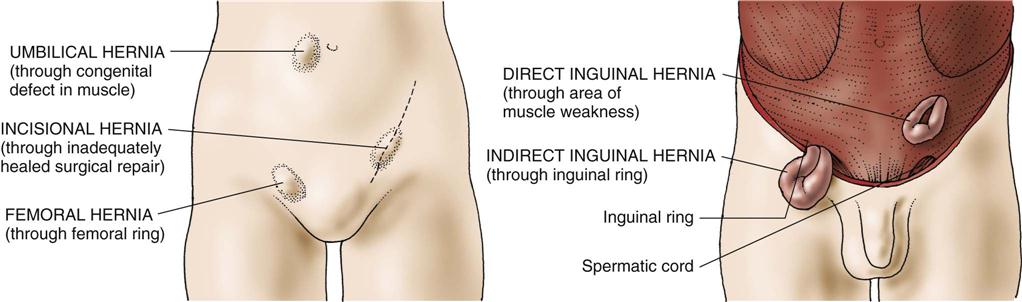

Depending on their location, hernias are classified as direct inguinal, indirect inguinal, femoral, umbilical, incisional, or epigastric (Figure 13-1). Hernias in any of these groups are either reducible or nonreducible; that is, the contents of the hernia sac either can be returned to the normal intra-abdominal position or are trapped in the extra-abdominal sac (incarcerated). The conditions preventing the return of the hernia contents to the abdomen can result from: (1) adhesions between the contents of the sac and the inner lining of the sac, (2) adhesions among the contents of the sac, or (3) narrowing of the neck of the sac. Patients with incarcerated hernias may have signs of intestinal obstruction, such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and distention. The greatest danger of an incarcerated hernia is that it may become strangulated. In a strangulated hernia, the blood supply of the trapped sac contents becomes compromised and eventually the sac contents necrose. When bowel is strangulated in such a hernia, resection of necrotic bowel, in addition to the repair of the hernia defect, becomes necessary. This is a surgical emergency.

Inguinal Hernias

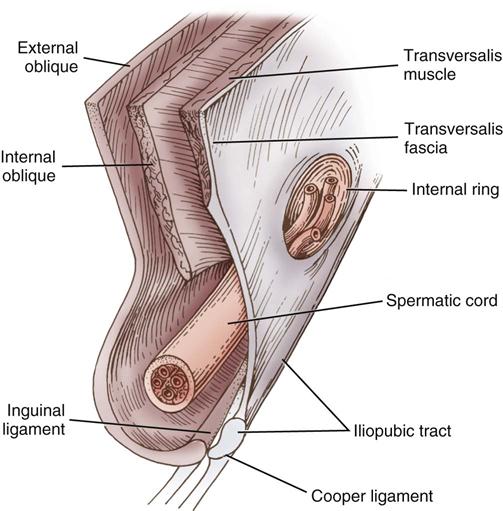

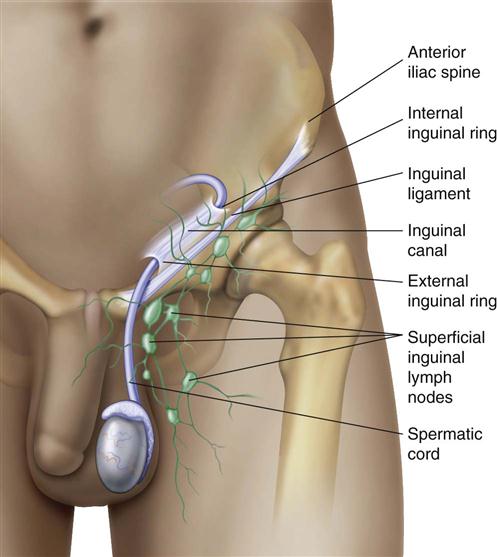

The anterolateral abdominal wall consists of an arrangement of muscles, fascial layers, and muscular aponeuroses lined interiorly by peritoneum and exteriorly by skin (Figure 13-2). The abdominal wall in the groin area is composed of two groups of these structures: a superficial group (Scarpa fascia, external and internal oblique muscles, and their aponeuroses) and a deep group (internal oblique muscle, transversalis fascia, and peritoneum).

Essential to an understanding of inguinal hernia repair is an appreciation of the central role of the transversalis fascia as the major supporting structure of the posterior inguinal floor. The inguinal canal, which contains the spermatic cord and associated structures in males and the round ligament in females, is approximately 4 cm long and takes an oblique course parallel to the groin crease. The inguinal canal is covered by the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle, which forms a roof (Figure 13-3). A thickened lower border of the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal (Poupart) ligament, which runs from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. Structures that traverse the inguinal canal enter it from the abdomen by the internal ring, a natural opening in the transversalis fascia, and exit by the external ring, an opening in the external oblique aponeurosis, to go to either the testis or the labium. If the external oblique aponeurosis is opened and the cord or round ligament is mobilized, the floor of the inguinal canal is exposed. The posterior inguinal floor is the structure that becomes defective and is susceptible to indirect, direct, or femoral hernias.

The key component of the important posterior inguinal floor is the transversalis muscle of the abdomen and its associated aponeurosis and fascia. The posterior inguinal floor can be divided into two areas. The superior lateral area represents the internal ring, whereas the inferior medial area represents the attachment of the transversalis aponeurosis and fascia to the Cooper ligament (iliopectineal line). The Cooper ligament is the site of insertion of the transversalis aponeurosis along the superior ramus from the symphysis pubis laterally to the femoral sheath. The inguinal portion of the transversalis fascia arises from the iliopsoas fascia and not from the inguinal ligament.

Medially and superiorly the transversalis muscle becomes aponeurotic and fuses with the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle to form anterior and posterior rectus sheaths. As the symphysis pubis is approached, the contributions from the internal oblique muscle become fewer and fewer. At the pubic tubercle and behind the spermatic cord or round ligament, the internal oblique muscle makes no contribution. The posterior inguinal wall (floor of the inguinal canal) is composed solely of aponeurosis and fascia of the transversalis muscle.

None of the three groin hernias (direct and indirect inguinal hernias and femoral hernia) develops in the presence of a strong transversus abdominis layer and in the absence of persistent stress on the connective tissue layers. When a weakening or a tear in the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and the transversalis fascia occurs, the potential for development of a direct inguinal hernia is established.

Femoral Hernias

When the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and its fascia are only narrowly attached to the Cooper ligament, a femoral hernia may develop. The resultant enlarged femoral ring and canal allows for the prominence of the iliofemoral vessels, giving rise to a femoral herniation.

The walls of the femoral sheath are formed anteriorly and medially from the transversalis fascia, posteriorly from the pectineus and psoas fascia, and laterally from the iliaca fascia. The pelvis ostium consists of a relatively fixed rim of bone and connective tissue: anteriorly and medially the iliopubic tract, posteriorly the superior ramus, and laterally the iliopectineal arch.

The femoral sheath is subdivided into three compartments. The lateral compartment contains the femoral artery, and the intermediate compartment contains the femoral vein. The medial compartment is the smallest and constitutes the femoral canal, which is formed anteriorly and medially by the iliopubic tract. This opening is bound laterally by the iliofemoral vessels and posteriorly by the superior pubic ramus and pectineus fascia. Superiorly, laterally, and inferiorly the fossa is formed by the falciform margin of the fascia lata. The iliopubic tract forms the superolateral border of the so-called triangle of pain, an area bounded medially by the spermatic vessels. In this area, tacking of surgical mesh (see Surgical Interventions) is avoided because of the risk of injury to the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve or the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (Sherwinter, 2011a).

Abdominal Hernias

The anterior abdominal wall is composed of external abdominal oblique muscles attached to a thick sheath of connective tissue called the rectus sheath. The linea alba extends superiorly and inferiorly from above the xiphoid process to the pubis. Beneath the rectus sheath lies the rectus abdominis muscles, laterally to the right and left of the linea alba. Lateral to the rectus abdominis is the linea semilunaris. The transversus abdominis muscles originate from the seventh to the twelfth costal cartilages, lumbar fascia, iliac crest, and inguinal ligament, and insert on the xiphoid process, the linea alba, and the pubic tubercle. The third layer of abdominal wall includes the internal abdominal oblique muscles originating from the iliac crest, inguinal ligament, and lumbar fascia, and inserting on the tenth to twelfth ribs and rectus sheath.

Direct and Indirect Inguinal Hernias

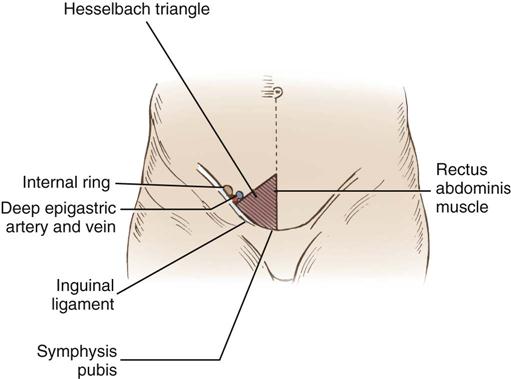

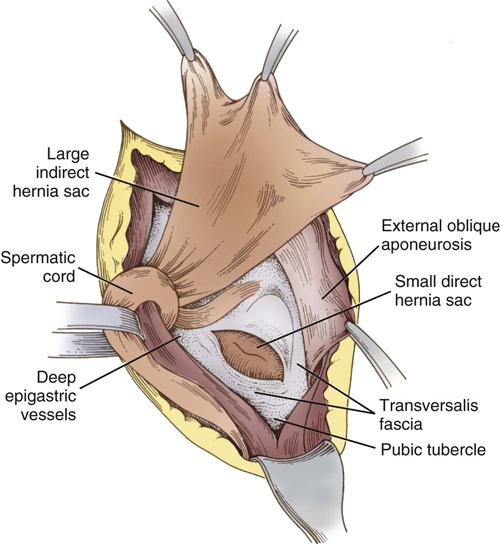

The deep epigastric vessels (inferior epigastric) arise from the external iliac vessels and enter the inguinal canal just proximal to the internal ring. The triangle formed by the deep epigastric vessels laterally, the inguinal ligament inferiorly, and the rectus abdominis muscles medially is referred to as the Hesselbach triangle (Figure 13-4). Hernias that occur within the Hesselbach triangle are called direct inguinal hernias. Indirect inguinal hernias occur laterally to the deep epigastric vessels. Both direct and indirect hernias represent attenuations or tears in the transversalis fascia (Figure 13-5).

Direct hernias protrude into the inguinal canal but not into the cord and therefore rarely into the scrotum. Direct inguinal hernias usually result from heavy lifting or other strenuous activities. Indirect hernias leave the abdominal cavity at the internal inguinal ring and pass with the cord structures down the inguinal canal. Consequently, the indirect hernia sac may be found in the scrotum. Indirect hernias may be either congenital, representing a persistence of the processus vaginalis, or acquired. In a congenital hernia the hernia sac has a small neck, is thin-walled, and is closely bound to the cord structures. In an acquired indirect hernia the neck is wide and the sac is both short and thick-walled. When both direct and indirect hernias are present, the defect is called a pantaloon hernia after the French word for “pants.”

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Assessment

Assessment begins with a thorough review of the patient’s history, which includes previous surgeries related to the herniated area. Information relating to a familial history of hernias, the patient’s nutritional status, duration of the symptoms, and a history of obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure, chronic cough, constipation, benign prostatic hypertrophy, intestinal obstruction, colon malignancy, or pregnancy are noted. A list of the patient’s current medications is collected, along with any history of chronic illness and allergies, including latex allergies (because a Penrose drain may be used during the procedure). The patient’s occupation and physical activities are listed. If it is part of institutional protocol, verification of preoperative showering or bathing with an antiseptic agent is done during assessment (Evidence for Practice).

Pain is often a notable symptom for the patient; it may be described as a burning sensation. An accurate description of the type and degree of pain is included in the assessment; obtain general information about onset, duration, severity, and quality of pain and about exacerbating and remitting factors. Patients often describe the feeling of a foreign body, or mass, at the hernia site. This may appear on arising in the morning and disappear while sleeping.

The diagnosis of hernias should be accompanied by clinical physical examination. Palpation of the herniated area reveals the contents of the hernia sac. Fingertip palpation allows the nurse to feel the edges of the external ring or abdominal wall. Having the patient stand and cough during the examination also assists in the evaluation of the herniated area. If a definitive diagnosis is not confirmed, ultrasonic scanning and imaging techniques (e.g., computed tomography [CT], herniography, standard radiography) may be used.

In some patients a hernia may cause no symptoms; its only sign may be a swelling or protrusion in a restricted area of the abdominal wall. If the hernia is unilateral, the patient notes the lack of a protrusion on the other side in comparison. The area may be visible when the patient stands or coughs and may disappear on reclining. Femoral hernias can be difficult to diagnose and may resemble an enlarged lymph node.

Formerly, routine studies (e.g., complete blood count [CBC], chest x-ray, and electrocardiogram [ECG]) were ordered preoperatively as elements in preanesthesia evaluation. It was believed that such studies determined the patient’s fitness for anesthesia and surgery. During the past few decades this practice has been a subject of much controversy. It has been somewhat established that performing routine screening tests in patients who are otherwise healthy is of little value in detecting diseases and in changing the anesthetic management or outcome. A thorough history and physical examination of the patient probably is the best method for screening diseases. This may be followed by selective tests based on the patient’s health, invasiveness of planned surgery, and potential for blood loss (Kumar and Srivastava, 2011). Thus an otherwise healthy patient presenting for hernia repair will have, in some institutions, only selective testing, which reduces cost without sacrificing safety or quality of surgical care.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of the patient undergoing hernia surgery might include the following:

Outcome Identification

Outcome measurement and management are important parts of perioperative nursing care. Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses could be stated as follows:

Planning

The perioperative nurse formulates a plan of care for the patient undergoing herniorrhaphy by assimilating knowledge pertaining to the anatomy involved, principles of asepsis, the planned surgical procedure, and requisite information provided/gained during planning specific to the surgical patient (Patient-Centered Care). Instrumentation, draping, and positioning for the patient’s surgery depend on the type of hernia and repair to be performed, for example, open versus laparoscopic.

A Sample Plan of Care for a patient having surgery for hernia repair is shown on p. 388.

Implementation

The patient is identified using two (2) identifiers, such as name and medical record number or date of birth. This should match the ID band. The surgical procedure/procedural consent should match the planned procedure for which the team is preparing. The patient may receive a general anesthetic, an inguinal nerve block, a field block, a spinal or epidural block, a regional anesthetic with sedation, or a local anesthetic with moderate sedation/analgesia. Chapter 5 describes required monitoring equipment, such as a three-lead or five-lead ECG, oxygen-saturation monitor, and blood pressure cuff, for patients receiving local anesthesia with or without moderate sedation/analgesia. An intravenous (IV) line is inserted for fluid replacement and medication administration. The surgical site is marked as part of the preoperative verification process and rechecked during the time-out; the site mark should be visible after draping. As part of the time-out, all members of the surgical team identify themselves and their roles and ask simple questions such as, “Does everyone agree that this is Patient X, undergoing a right inguinal hernia repair?” The perioperative nursing team reviews critical checklist information (AHRQ, 2013; DeJohn, 2013) such as confirming sterility of the instruments and supplies (including indicator results); discusses any equipment issues or concerns; notes whether antibiotic prophylaxis has been given within the last 30 to 60 minutes (antibiotics should be given as close to the time of incision as possible) and whether re-dosing is anticipated (re-dosing is based on the patient’s body mass index [BMI] and whether the procedure will last for more than 3 hours [Moody and Davis, 2013]); confirms mesh implant/material is available (as appropriate); and verifies whether essential imaging studies are displayed, if applicable. A preop briefing is held in many institutions, during which surgical team members discuss the planned procedure, potential patient needs, and any anticipated problems so they can be resolved prior to the patient being brought in to the operating room (OR) (Braman, 2013) (Research Highlight).

The patient is usually positioned supine (see Chapter 6) following basic prepping and draping procedures (see Chapter 4). As with any surgical procedure, the prep solution must dry before the start of the surgical procedure as part of fire safety measures. To maintain the patient’s dignity and modesty, expose only the part of the patient’s body necessary for antimicrobial skin preparation. Instruments used for hernia repair are those found in standard laparotomy sets, laparoscopy sets, or minor sets. Additional supplies and anticipatory preparation for other patient care needs depend on the perioperative nurse’s knowledge of the planned procedure as well as communication and teamwork. Research suggests that interventions to improve OR teamwork and communication may have beneficial effects on technical performance as well as on patient outcomes. Improving the effectiveness of communication among caregivers remains a National Patient Safety Goal for The Joint Commission (TJC, 2013).

Self-retaining retractors, such as a Weitlaner, facilitates separation of tissue layers. A moistened Penrose drain is often used to retract the spermatic cord structures for better exposure. Because the peritoneal cavity may be entered in this procedure, soft goods, sharps, and instrument counts are initiated. Different size meshes should be available. There are many brands and types of mesh for the repair of inguinal hernias: absorbable and permanent synthetic meshes; allograft material; and xenograft material, such as sterile lyophilized acellular porcine collagen. Mesh is available in flat sheets, precut segments, and three-dimensional forms. Some mesh products for hernia repair include additional components to resist adhesions, to allow for fixation, or to prevent infection (Pickett, 2013).

The mesh must be large enough to produce a wide overlap beyond the defect’s edges. A polypropylene or polyester mesh is often used. There are lighter, more porous meshes that maintain the strength of the repair but are credited by the manufacturer with reducing the inflammatory response. The mesh chosen is primarily based on surgeon preference and training (Sherwinter, 2011b).

With a sliding or an incarcerated hernia, the possibility of having to enter the peritoneal cavity must be considered. If the hernia is strangulated, necrotic bowel is resected and instruments for performing a bowel anastomosis are added. If antibiotics are added to irrigation solution, safe medication practices are followed. All medications and solutions on and off the sterile field are labeled. When the antibiotic solution is passed to the surgeon, the surgical technologist or other scrub person should announce the name and strength of the antibiotic solution to be used for irrigation.

Repair of an inguinal hernia includes approximation of the transversalis fascia with a heavy nonabsorbable type of suture; mesh may also be used. With some indirect hernias, only two or three sutures may be necessary. In other cases, however, up to 10 sutures in succession may be needed. Scarpa fascia is approximated with absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed by one of several methods. Several types of prosthetic mesh are available and often used to support hernia repair.

A laparoscopic hernia repair is technically similar to an open laparotomy, but the instrumentation includes laparoscopic equipment. There is always a possibility that a laparoscopy may become a laparotomy, and instrumentation for this change in procedure is always available.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the patient having repair of a hernia includes examining all skin surfaces to assess variances with preoperative assessment data. The patient should awaken from general anesthesia, if it is used, in a reasonable amount of time without exhibiting signs of anxiety or extreme disorientation. Extubation should be timely to avoid stress on the repaired hernia site. Evaluation of the patient’s status can be phrased in outcome statements such as the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree