Data from Cohen RA, Brown RS. Clinical practice. Microscopic hematuria. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2330–2338.

Risk Factors

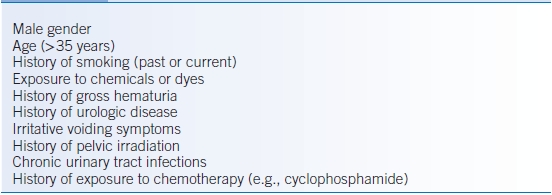

It is impossible to generalize risk factors for hematuria since there are so many different causes. However, common risk factors for hematuria associated with urinary tract malignancy are summarized in Table 25-2.1

TABLE 25-2 Risk Factors for Urinary Tract Malignancy

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of hematuria can be made by serial visual or microscopic assessments of the urine to confirm the persistent presence of blood. The purpose of the ensuing workup is to localize the cause of the hematuria and provide the appropriate treatment.

Clinical Presentation

History

- Although many causes of hematuria are asymptomatic, a detailed history can often identify symptoms that are suggestive of specific causes of hematuria.

- Pain:

- Colicky pain at the costovertebral angle (CVA) or flank with radiation to the groin may indicate a ureteral stone but can be associated with blood clot or sloughed renal papilla.

- A history of dysuria or urinary frequency suggests a urinary tract infection (UTI).

- Colicky pain at the costovertebral angle (CVA) or flank with radiation to the groin may indicate a ureteral stone but can be associated with blood clot or sloughed renal papilla.

- Urine flow: urinary hesitancy, dribbling, or weak urinary stream accompanies bladder obstruction from an enlarged prostate, stone, or tumor.

- Timing:

- Cyclical hematuria in women raises concern for genitourinary tract endometriosis.

- A history of heavy physical activity may explain transient (<48 hours) microscopic hematuria but does not exclude other underlying pathologic conditions.

- Cyclical hematuria in women raises concern for genitourinary tract endometriosis.

- Family history: A family history of hematuria can often be found in individuals with kidney stones, polycystic kidney disease, or congenital disease of the glomerular basement membrane, such as thin basement membrane disease and Alport syndrome.

- Associated illnesses:

- Patients on anticoagulation may have hematuria from nonglomerular sites of bleeding.

- Individuals with sickle cell disease or trait can develop renal diseases with hematuria.

- Infections

- A history of hematuria 1 to 2 weeks after pharyngitis or skin infection suggests poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN).

- IgA nephropathy can present with episodic gross hematuria in the setting of upper respiratory infections (URI).

- Bacterial endocarditis, sepsis, abscesses, or infection of an indwelling foreign body can be associated with a proliferative glomerulonephritis. Other infections such as viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C) and syphilis can also cause a variety of glomerulopathies.

- A history of hematuria 1 to 2 weeks after pharyngitis or skin infection suggests poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN).

- Autoimmune diseases: immune complex–mediated glomerular diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus or systemic vasculitis can present with arthritis, arthralgias, fever, or rashes.

- Patients on anticoagulation may have hematuria from nonglomerular sites of bleeding.

Physical Examination

- Thorough physical examination including vital signs (especially blood pressure) and assessment of volume status is important. The presence of edema and hypertension favors a glomerular cause of hematuria.

- Fever, CVA tenderness, or suprapubic tenderness may suggest infection.

- Polycystic kidney or distended bladder may be palpable on abdominal examination.

- Skin rashes, arthritis, or heart murmurs can often be seen with systemic vasculitis, autoimmune glomerulonephritis, and infectious glomerulonephritis.

- Digital rectal examination helps with diagnosis of prostate enlargement, masses, or tenderness.

- Vaginal examination should be performed in women to exclude vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic Testing

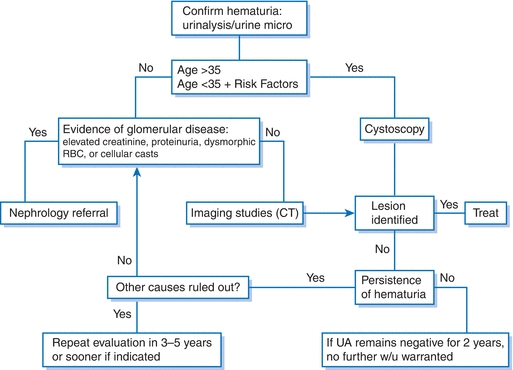

An overview of the workup for hematuria is summarized in Figure 25-1.

Figure 25-1 Algorithm for the evaluation of microscopic hematuria.

Laboratories

- The urinalysis (dipstick and micro) is the initial test for diagnosis and confirmation of hematuria. The urinalysis is able to distinguish true hematuria from urine that is discolored due to chemical pigments, food metabolites, or medications (e.g., bilirubin, porphyrins, beets, blackberries, blueberries, levodopa, metronidazole, nitrofurantoin, pyridium, phenytoin, rifampin).5

- The urine evaluation can also help differentiate glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria.

- The dipstick is able to detect significant excretion of negatively charged proteins. While it may miss microalbuminuria seen in the earliest stages of nephropathy, a positive urine dipstick is suggestive of glomerular damage and should be further assessed by an estimate of renal function and quantification of proteinuria.

- Urine microscopy can detect the presence of dysmorphic RBCs and cellular casts. When coupled with proteinuria (≥0.5 g/day) and/or renal insufficiency, it suggests renal parenchymal disease and warrants further nephrologic workup.

- The dipstick is able to detect significant excretion of negatively charged proteins. While it may miss microalbuminuria seen in the earliest stages of nephropathy, a positive urine dipstick is suggestive of glomerular damage and should be further assessed by an estimate of renal function and quantification of proteinuria.

- Further laboratory testing can be guided based on history, physical examination, and initial lab testing.

- Urine culture is indicated if pyuria or bacteriuria is present. Repeat urinalysis 6 weeks after appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis evaluates for suspected sickle cell disease or trait.

- Antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, complement levels, cryoglobulins, HIV testing, and viral hepatitis serology are used for evaluation of glomerular hematuria.

- Urine cytology is used for patients at risk for genitourinary malignancies but not for routine screening. If positive, cystoscopy is warranted.

- Urine culture is indicated if pyuria or bacteriuria is present. Repeat urinalysis 6 weeks after appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Imaging

- Imaging should be performed in patients with no evidence of glomerular hematuria.

- CT scan with and without intravenous (IV) contrast is currently the preferred initial imaging modality. It has excellent sensitivity for stones and solid masses. In patients with a contraindication to CT (contrast allergy, pregnancy, renal insufficiency), MRI with and without IV contrast can be considered.

- Ultrasonography is an effective and safe imaging modality in patients with contraindications to CT/MRI and is preferred in pregnancy.

- Retrograde pyelogram (RPG) provides an alternative for the evaluation of upper genitourinary tracts.

- Intravenous urography (IVU) was traditionally the initial imaging modality of upper urinary tracts but has been largely replaced by other methods.

Diagnostic Procedures

- Per the 2012 AUA guidelines, cystoscopy should be performed on all patients with hematuria ≥35 years old, with or without risk factors for urinary tract malignancy. Patients <35 years should have cystoscopy if underlying risk factors for malignancy are present.1

- Referral to nephrology with a possible kidney biopsy is indicated if glomerular pathology is suspected.

TREATMENT

- The treatment of hematuria is entirely dependent on the cause.

- See Chapter 24 for treatment of glomerulonephritis.

FOLLOW-UP

- A patient with a history of persistent microscopic hematuria and two consecutive negative annual urinalyses does not need any further urinalysis or other evaluation.1

- For persistent microscopic hematuria after negative workup, yearly urinalysis should be conducted.1

- Repeat evaluation in 3 to 5 years should be considered for persistent or recurrent microscopic hematuria after initial negative workup.1

Nephrolithiasis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Kidney stones are crystalline structures in the urinary tract that have achieved sufficient size to cause symptoms or be visible by radiographic imaging techniques.

Epidemiology

- Nephrolithiasis is a common condition that affects men twice as often as women (lifetime risk of 12% vs. 6%).6

- The peak age of onset is the third decade, with increasing incidence until age 70.

- Prevalence is influenced by age, sex, race, body size, and geographic distribution.

Classification

- Calcium stones account for approximately 80% of all stones and are composed of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or both.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree