Chapter Fifty. Health challenges and problems in neonates of low birth weight

Introduction

This chapter aims to define low birth weight, consider some of the common causes and address some of the most prevalent health challenges and problems that may occur in such neonates. The complexity and diversity of health problems require all those caring for these neonates to have specialist knowledge and expertise and this chapter aims to offer a résumé of relevant biological principles that may guide practice. The chapter will also build on some of the diagnostic accounts of congenital abnormalities in Chapter 15, giving due consideration to relevant aspects of physiology, pathophysiology and, where appropriate, therapeutic caring interventions.

Defining low birth weight

The term low birth weight applies to all neonates, regardless of gestational age, whose body weight at birth is less than 2500 g. The improved survival of neonates weighing less than 1000 g required the introduction of the term extremely low birth weight in order to contextualise the challenges and outcomes related to these very small neonates. Given that about 70% of perinatal mortality (total of stillbirths and neonatal deaths) occurs in the 7% of babies whose birth weight is low or very low, this group of neonates clearly encounters complex problems. Regardless of the cause, these neonates are often grouped according to their birth weight in the following manner (England 2003):

• Low birth weight (LBW) includes neonates weighing 2500 g or less at birth.

• Very low birth weight (VLBW) includes neonates weighing 1500 g or less at birth.

• Extremely low birth weight (ELBW) includes neonates weighing under 1000 g at birth.

Causes of low birth weight

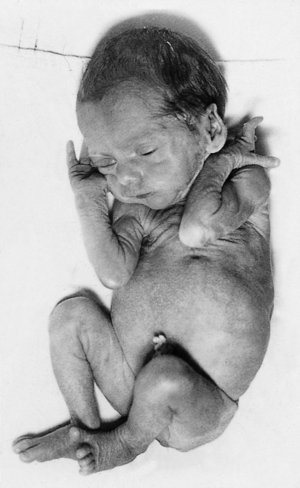

The two most dominate reasons for a neonate’s low birth weight are prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) (Fig. 50.1). Premature neonates are born before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy and the term prematurity is used regardless of birth weight. Neonates who are small for gestational age (SFGA) weigh less at birth than would be predicted for their gestational age. This group usually includes neonates born below the 10th centile. As these two groups of neonates are likely to present with a range of problems requiring specialist intervention, practitioners must be capable of assessing them at birth and identifying and managing problems which are present. Ongoing vigilance is needed in recognising new problems which evolve in the first few days or even weeks of life. Specialist knowledge, clinical expertise and vigilance are crucial in providing optimal care.

|

| Figure 50.1 Low-birth-weight babies. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Assessment of gestational age

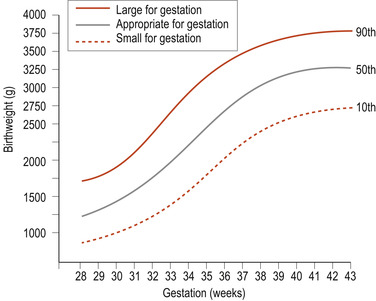

One of the tools commonly used in assessing such neonates is centile charts (Fig. 50.2) which help to define the small-for-gestational-age neonates by using their birth weight which is invariably more than two standard deviations below the mean or less than the 10th percentile of a population-specific birth weight for gestational age. Whilst variations in fetal growth exist, birth weight is frequently used to distinguish between neonates who are small for gestational age from those who are small but normal for gestational age. Assessments of fetal growth, development and maturation must take into consideration variations in genetic and environmental factors which are known to impact on the expectant mother’s health as well as the growth of her fetus(es).

|

| Figure 50.2 A centile chart, showing weight and gestation. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

In most instances, assessment of fetal growth would be based on the length of gestation by taking into account the onset of the last menstrual period, the size and shape of the growing uterus and maternofetal hormone profile. Ultrasonic studies, and in some instances, amniocentesis, provide additional information when required. Most fetuses fall into a symmetric or asymmetric growth pattern. Symmetric growth implies that both brain and body growths are limited, whereas asymmetric growth implies that body growth is restricted to a greater extent than head and brain growth. The mechanisms for such asynchronous growth are not understood although Anderson & Hay (1999) suggest that increased cerebral blood flow relative to the remainder of the systemic circulation may contribute. The birth of low-birth-weight neonates generally warrants the presence of experienced paediatricians at the delivery.

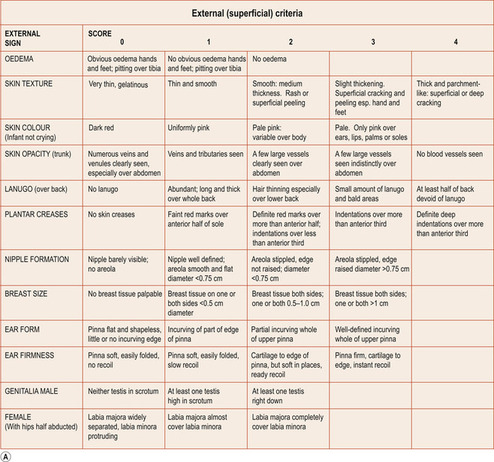

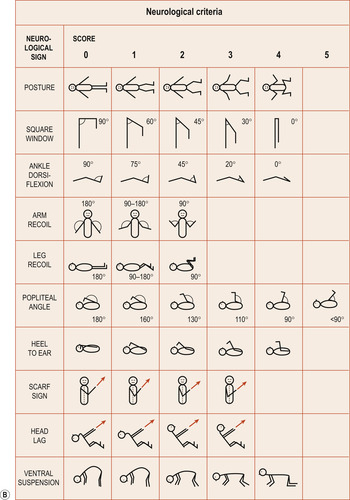

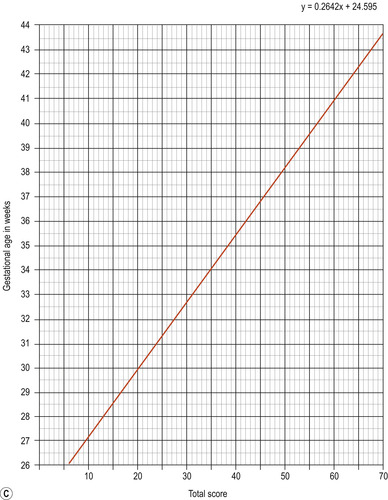

In addition to establishing the birth weight, length, head circumference and gestational age, all small neonates must undergo a thorough physical assessment that may include scoring of neurological and neuromuscular capabilities initially devised by Dubowitz et al (1970) but used widely in the United Kingdom (Fig. 50.3). However, as this scale awards points for neurological states as well as external criteria, it is not always suitable for assessing the gestational age of sick neonates. The Parkin score (Parkin et al 1976), which uses exclusively external criteria, is quicker to use, though less accurate (Fig. 50.4). However, assessments may have adverse effects on the stability of the neonate’s condition. They are less useful with the more sophisticated fetal assessments using ultrasound, unless the mother is seen for the first time in labour (England 2003).

|

|

|

| Figure 50.3 (A)–(C) Dubowitz scoring system. (Adapted from Dubowitz L M S, Dubowitz V, Goldberg C 1970.) |

|

| Figure 50.4 Parkin, Hey and Clowes scoring system. (Reproduced from Parkin et al 1976.) |

The preterm neonate

Health challenges experienced by premature neonates can, to a large extent, be attributed to immaturity of body systems (Fig. 50.5), which means that some organs and systems have not reached the fully functional state required for adaptation to extrauterine life.

|

| Figure 50.5 A preterm baby born in 1954 at 28 weeks gestation and weighing 1.1 kg. He was discharged in good health after 11 weeks in hospital. (From Kelnar C, Harvey D, Simpson C 1995, with permission.) |

Characteristics of the premature neonate

• A large head and small face in proportion to the body.

• Brain and spinal cord tissue is fragile and much more susceptible to injury.

• Soft skull bones with widely spaced sutures and large fontanelles.

• Neonates born before 24 weeks may present with fused eyelids.

• The skin is red and thin, subcutaneous fat is almost absent and surface veins are prominent.

• Lanugo is present, depending on the gestational age.

• A small narrow chest with little breast tissue.

• A large prominent abdomen with a low-set umbilicus.

• Thin limbs with soft nails not reaching the ends of the digits.

• Small genitalia: in girls, the labia majora do not cover the labia minora; in boys, the testes have not descended into the scrotum.

• Muscle tone is poor and all four limbs may be held in the extended position.

• Normal reflexes, including sucking, gagging and coughing may be absent or feeble.

Causes of preterm birth

Although preterm births occur spontaneously, in many circumstances the sequence of events may be medically controlled for maternal or fetal safety. Whilst 40% of such births have no established causes, a range of contributing factors such as physical disorders in the fetus or the mother, or the mother’s social class, may play a key role (Table 50.1). This is not surprising as many suboptimal health problems appear to be the consequence of interplays between genetic and environmental factors (see Ch. 8 and Ch. 15).

| Fetal causes | Maternal causes |

|---|---|

| Multiple pregnancy | Pre-eclampsia |

| Polyhydramnios | Antepartum haemorrhage |

| Congenital abnormalities | Rhesus incompatibility Systemic maternal disease such as diabetes mellitus Pyrexia associated with viral infections Smoking, alcohol and drug abuse Maternal short stature Cervical incompetence Maternal age and parity Inappropriate maternal nutrition |

Immediate management

Proactive care of the premature neonate aims at supporting the physiological shortfalls which are apparent at birth. Usually this care is initiated before or during labour to ensure the neonate’s survival. Ideally all premature neonates should be delivered in maternity departments with specialist neonatal care facilities as the transfer of such small neonates is fraught with problems and increased risks.

In labour

Ideally, prophylactic corticosteroids should be administered to a mother who is in early labour and likely to give birth. Such practice is reviewed by Roberts & Dalziel (2006) who recommend that the administration of 24 mg betamethasone or dexamethasone or 2 g hydrocortisone administered as a single course in divided dosages will reduce the severity of respiratory distress syndrome and intraventricular haemorrhage with no apparent adverse effects to the fetus/neonate. The pharmacodynamic effects of such corticosteroid administration are not fully understood although Hansen & Hawgood (2003) suggest that such therapeutic interventions vastly outweigh any potential risks to the neonate possibly by stimulating lung maturation and facilitating gas exchange which reduces the hypoxia thought to contribute to intraventricular bleeding. The positive clinical outcomes in preterm neonates support this practice.

The delivery of the fetus must be given careful consideration. Some have advocated delivery of the fetus by elective caesarean section because this mode of delivery may improve the outcome for VLBW neonates, particularly where the fetus is a breech presentation (Gilady et al 1996). However, Grant & Glazener (2003) conclude that there is ‘not enough evidence to evaluate a policy for elective caesarean delivery for small neonates’.

In cases where vaginal delivery is the elected choice, an episiotomy is generally advocated and forceps may be used to facilitate the birth and so lessen the risk of intracranial haemorrhage. In these circumstances care must be taken to ensure that the maternal medication such as analgesia does not compromise the fetus’s scope for initiation of spontaneous respiration at birth.

At birth

The delivery suite must be equipped for resuscitation of the neonate if this is needed. Ideally, an experienced paediatric team should be present during the delivery. Some neonates have weak respiratory muscles and immature respiratory centres both of which may cause difficulties in establishing effective respiration. In such circumstances, elective endotracheal intubation may improve the neonate’s chances of survival and well-being. Many of these neonates, although well at birth, go on develop respiratory, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal problems and a timely elective intervention may be advantageous.

The ambient temperature of the delivery suite and the neonatal unit should be no less than 24°C. As most of these neonates have limited or no subcutaneous adipose tissue, thermoregulation will be a problem and effective drying and warm swaddling are advocated. If the neonate’s respiratory and cardiovascular functions are satisfactory, the parents should be allowed to hold their baby. However, if the mother wishes to have a more direct skin-to-skin contact with her baby, then warm protective blankets may be required. If the neonate needs cardiopulmonary resuscitation, an overhead radiant heater should be used to ensure that the immediate vicinity is warm to prevent heat loss.

Ongoing care of premature neonates

Potential problems

Premature neonates may present with a potential for a range of problems which may include:

• Respiratory problems such as apnoea, respiratory distress syndrome and later bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

• Metabolic problems such as hypoglycaemia and hypocalcaemia.

• Structural organic problems such as necrotising enterocolitis and periventricular and intraventricular haemorrhage.

• Haematological problems such as jaundice and anaemia.

• Haemodynamic problems such as persistent fetal circulation.

Any clinical evidence that some of the above problems exist or could develop will require the premature neonate to receive specialist supportive care which should include:

• Maintenance of ambient and body temperature.

• Proactive support for respiratory and cardiovascular and potential neurological dysfunction.

• Proactive support for gastrointestinal function, supportive nutrition and supportive intervention.

• Proactive management of metabolic problems.

• Proactive support to maintain effective renal perfusion and glomerular filtration.

• Prevention of infection.

• Monitoring of excretion: urine, meconium, changing stool patterns.

• Supportive intervention that fosters bonding between the parents and their baby.

Maintenance of temperature

Compared with term infants, premature infants have a narrower thermoneutral range where heat production cannot always match the rate of heat loss. This is further compromised by considerable heat loss due to a larger head-to-body ratio and the exaggerated body surface area that is characteristic of all premature and small-for-gestational-age neonates. The greater heat loss makes additional metabolic demands on the neonate whose ability to assimilate nutrients and exchange gases can be compromised by multi-organ immaturity. Therefore, although neonates are dependent on oxygen and glucose as energy, delivery of these substrates must not exceed the physiological norm.

To ensure that the neonate’s body temperature is kept within the very narrow physiological range, ambient temperatures are held between 26°C and 28°C and the incubator temperature at about 36°C to maintain the neonate’s body temperature at about 37°C. A temperature-monitoring skin probe (skin servocontrol) can be used to control the incubator temperature, allowing it to adjust automatically in response to changes in the neonate’s temperature. Neonates born before 30 weeks of gestation have porous skin, allowing water to evaporate and increase heat loss. Such neonates should be nursed in a humid atmosphere for the 1st week of their life.

Respiration

Premature neonates generally have a respiratory rate that averages between 60 and 80 breaths/min (Hansen & Hawgood 2003) with equal time for inspiration and expiration (ratio of 1:1). To ensure energy-efficient gas exchange, premature neonates use the apnoeic form of respiration: for instance, 5 short breaths are followed by a rest period. This physiological apnoea permits gas diffusion across the inflated alveolae and the pulmonary capillary interface. Ongoing observation and hourly monitoring should ensure that neonate’s respiratory functions are assessed and distress is noted, including:

• The shape of the chest, its symmetry, inflation and contour; asymmetrical chest expansion.

• The colour of the skin; evidence of central and peripheral cyanosis.

• The rate and rhythm and effort on respiration; evidence of sternal and subcostal recession.

• Breath sounds on chest auscultation; evidence of expiratory or inspiratory wheeze.

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen therapy may be required in circumstances where respiratory distress and cyanosis develop (see Ch. 51). In such instances the temperature, humidity, flow rate and concentration of inspired oxygen must be monitored (Anderson et al 2006

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree