Head and Neck

Adriana Acurio

Jerome B. Taxy

Introduction

Intraoperative consultation in head and neck cancer management concerns tumor diagnosis, margin evaluation, and nodal status, one or all of which help to determine the extent of surgery. These issues will be addressed here related to conventional mucosal squamous carcinoma and salivary gland tumors, the most common tumors in this anatomic region. The tissue artifacts commonly encountered on frozen sections and the effects of (neo) adjuvant therapy as possible pitfalls in interpretation will also be discussed. In addition, consideration will be given to the relatively recent application of frozen section to the management of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis as a guide for surgical debridement, which is an essential part of the therapy for this disease. Studies on the accuracy of frozen section in head and neck cancers suggest it is reliable, with an accuracy rate of 98% and a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 99%, respectively (1).

Mucosal Lesions of the Head and Neck: Indications and Intraoperative Questions

An Immediate Diagnosis on a Primary Lesion

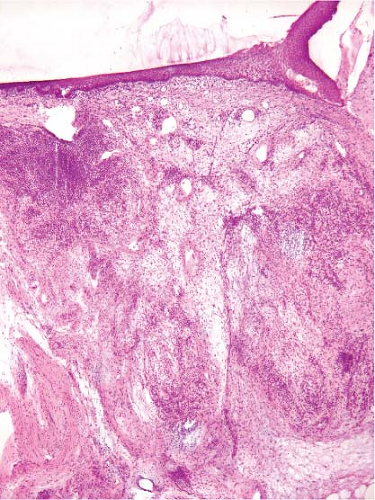

While most primary diagnoses of squamous cell carcinoma rely on routinely processed endoscopic biopsies or excisions, a request for an immediate specimen evaluation reflects a set of clinical circumstances specific to each patient. An intraoperative diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma on an untreated primary mucosal lesion, or a posttreatment persistent/recurrent lesion, may be requested to ensure adequacy or to justify proceeding with an immediate wide resection (Fig. 10.1). If the frozen section is done for adequacy assessment, additional tissue should be requested not to be frozen. A frozen section may be helpful not only to establish a diagnosis but, if in situ carcinoma is identified, to confirm that the lesion is primary (Fig. 10.2). The presence of carcinoma may also initiate an immediate neck dissection.

Most difficulties in frozen section analysis of mucosal biopsies center on differentiating malignant from reactive lesions. Foremost among the latter are flat lesions simulating dysplasia but associated with infections or prior treatment. In addition, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may coexist with

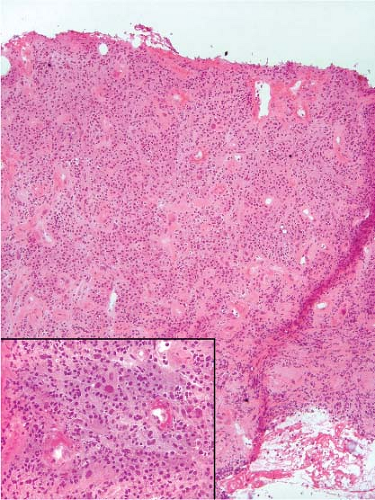

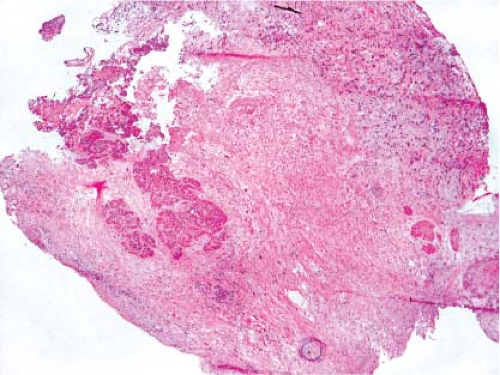

ulcers or even some benign neoplastic lesions. Crush artifact, especially in intensely inflamed areas or involving minor tonsillar tissue, is a potential source of confusion, and interpretation of such areas should be avoided (e-Fig. 10.1). Potentially confusing surface mucosal changes include edema and chronic inflammation (Fig. 10.3) or ulceration with the association of prominent atypical (reactive) stromal cells and granulation tissue (Fig. 10.4), reflective of prior treatment. In conjunction with these features, there may be isolated nests of squamous epithelium highly suggestive of infiltrating cancer (e-Fig. 10.2). It may be diagnostically uncertain at the time of the frozen section that such areas are reactive related to prior treatment or a solitary focus of residual/persistent cancer. The pathologist may be reluctant

to establish a malignant diagnosis based on such an isolated observation, especially if a radical procedure will be the result. These circumstances are common enough such that the frozen section might best be reported as deferred or descriptively as “atypical,” serving to alert the surgeon to obtain additional samples not to be frozen. The pathologist will also then have time to study the permanent material and arrive at a secure diagnosis.

ulcers or even some benign neoplastic lesions. Crush artifact, especially in intensely inflamed areas or involving minor tonsillar tissue, is a potential source of confusion, and interpretation of such areas should be avoided (e-Fig. 10.1). Potentially confusing surface mucosal changes include edema and chronic inflammation (Fig. 10.3) or ulceration with the association of prominent atypical (reactive) stromal cells and granulation tissue (Fig. 10.4), reflective of prior treatment. In conjunction with these features, there may be isolated nests of squamous epithelium highly suggestive of infiltrating cancer (e-Fig. 10.2). It may be diagnostically uncertain at the time of the frozen section that such areas are reactive related to prior treatment or a solitary focus of residual/persistent cancer. The pathologist may be reluctant

to establish a malignant diagnosis based on such an isolated observation, especially if a radical procedure will be the result. These circumstances are common enough such that the frozen section might best be reported as deferred or descriptively as “atypical,” serving to alert the surgeon to obtain additional samples not to be frozen. The pathologist will also then have time to study the permanent material and arrive at a secure diagnosis.

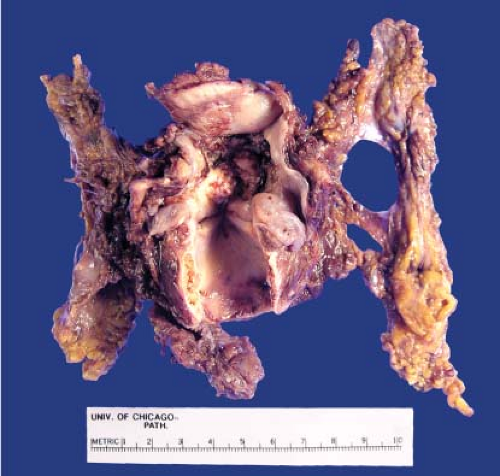

Figure 10.1 Gross photograph of a poorly circumscribed ulcerated white lesion of the retromolar trigone, excised and appropriately marked with sutures. |

In addition, related to the assessment of surface changes and the appreciation of changes in the underlying stroma is the presence of scar tissue and prominent blood vessels suggesting desmoplasia (e-Fig. 10.3).

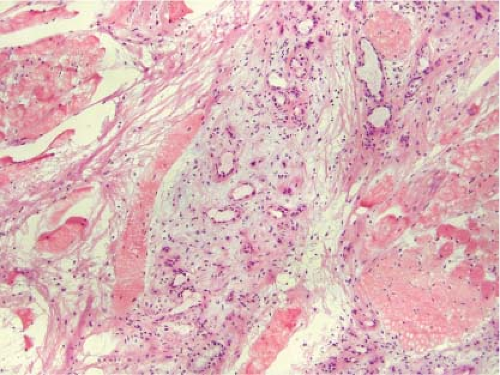

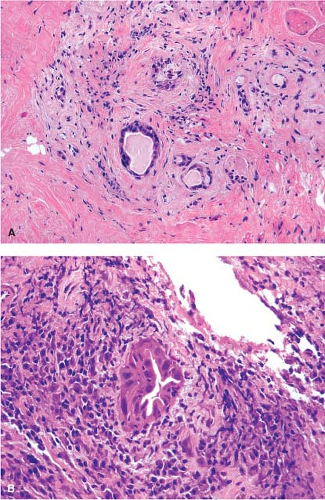

Especially difficult in this regard are the changes in minor salivary gland tissue reflective of previous treatment. These changes histologically simulate the changes of necrotizing sialometaplasia (Figs. 10.5 and 10.6, e-Figs. 10.4 and 10.5) and are principally characterized by the preservation of the lobular growth pattern, despite the nuclear atypia and squamoid features. Given the potential consequences, a frozen section diagnosis of infiltrating cancer should be unequivocal, demonstrating irregular growth patterns and a desmoplastic reaction (Fig. 10.7, e-Fig. 10.6).

Especially difficult in this regard are the changes in minor salivary gland tissue reflective of previous treatment. These changes histologically simulate the changes of necrotizing sialometaplasia (Figs. 10.5 and 10.6, e-Figs. 10.4 and 10.5) and are principally characterized by the preservation of the lobular growth pattern, despite the nuclear atypia and squamoid features. Given the potential consequences, a frozen section diagnosis of infiltrating cancer should be unequivocal, demonstrating irregular growth patterns and a desmoplastic reaction (Fig. 10.7, e-Fig. 10.6).

The Status of a Mucosal Resection Margin

While the histologic changes in the margins are similar to what has been described earlier for primary mucosal lesions, at stake is whether additional tissue needs to be excised if the margin is involved. The more basic questions should be the following: What constitutes involvement, and what quantitative distance represents an adequate margin? That the answers to these questions are not readily apparent nor are likely to be adequately resolved by frozen section study does not prevent them from being frequently asked with a plethora of specimens (2).

The known multifocality (“field effect”) of squamous carcinoma and its dysplastic precursors in the upper aerodigestive tract, the uncertain predictive value of dysplasia related to the subsequent development of invasive cancer, and the lack of agreement as to what constitutes an adequate or involved (“positive”) margin makes it arguable whether preinvasive dysplasia should be reported in an intraoperative setting. The grading of squamous dysplasia in the oral cavity traditionally utilizes the same

system as in the uterine cervix but is without the predictable correlation with the subsequent development of or coexistence with invasive squamous cancer. Experience has also shown that invasive squamous carcinoma in the head and neck is often not associated with typical in situ carcinoma. Being aware of the treatment algorithm, which may vary among surgeons, is critical in the interpretation of these samples.

system as in the uterine cervix but is without the predictable correlation with the subsequent development of or coexistence with invasive squamous cancer. Experience has also shown that invasive squamous carcinoma in the head and neck is often not associated with typical in situ carcinoma. Being aware of the treatment algorithm, which may vary among surgeons, is critical in the interpretation of these samples.

It is easy to understand that surgeons have an aversion to cutting across invasive tumor and to agree that this observation should be reported. Indeed, in an extensive review of the literature, Batsakis (3) suggests that only involvement by invasive carcinoma should be reported as positive. Therefore, the clinical significance of preinvasive dysplasia related to local recurrence and survival is debatable (2,3,4,5), even as it has been suggested that approximately 75% of patients with positive surgical margins will either develop local recurrence or demonstrate residual disease upon reoperation (6). The most widely accepted, albeit arbitrary, designation of a close margin is tumor within 5 mm of the inked surgical margin (7), risking more local recurrences and poorer overall prognosis. The 5-mm designation is modified for extralaryngeal sites, such as the oral cavity and oropharynx where a 10-mm margin of normal tissue is considered more appropriate (5). It is possible that the increased numbers of lymphovascular spaces in these sites predispose for local spread and recurrence and therefore determine the need for wider margins.

Although there are suggestions that frozen sections for margins in head and neck cancers be abandoned (8), presently this might be a tough case to make to the surgeons. The surgical goal of complete extirpation of a tumor and its potential dysplastic accompaniers helps to explain the many samples for frozen section frequently submitted from patients undergoing a definitive resection. Frozen section carries a potential for interpretative uncertainty especially considering the common artifacts of crushed cells, cracking and knife marks, the frequently encountered tangential

sections and treatment effects which can easily complicate the tissue evaluation. The morphologic challenge becomes more apparent when one considers that even with properly fixed and embedded samples under permanent conditions, there is difficulty in differentiating ordinary squamous or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasias from intramucosal squamous dysplasia, not to mention grading it. It is perhaps more than an understatement to say that margin assessment by frozen section can be uncertain.

sections and treatment effects which can easily complicate the tissue evaluation. The morphologic challenge becomes more apparent when one considers that even with properly fixed and embedded samples under permanent conditions, there is difficulty in differentiating ordinary squamous or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasias from intramucosal squamous dysplasia, not to mention grading it. It is perhaps more than an understatement to say that margin assessment by frozen section can be uncertain.

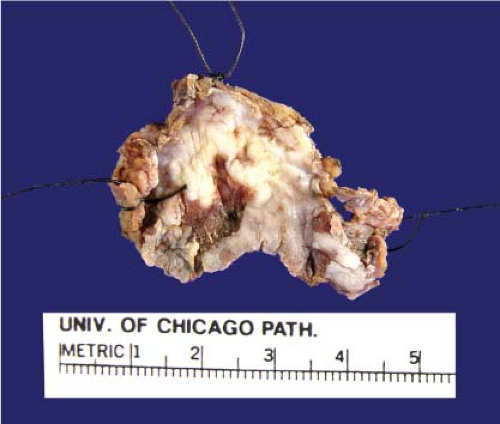

In addition to awareness of the treatment algorithm, margin assessment should ensure that the pathologist has some knowledge of or actually is able to examine the gross specimen. Given the inherent complexity of head and neck anatomy, orientation of the resection specimen by the surgeon in person, by diagram, or in the form of suture designations is essential. In addition, measurements, photographs, and/or specimen diagrams should be prepared before samples are taken for frozen section (Figs. 10.1, 10.8, and 10.9, e-Figs. 10.7 and 10.8). From large specimens, the manner in which the tissue is mounted and sectioned may vary. Right angle or perpendicular

gross sectioning best allows for thorough macroscopic analysis including measurement of the distance from the lesion to the nearest surgical margin (e-Fig. 10.8). The selected area for frozen section analysis should be visually closest to the margin. Parallel or en face sectioning does provide a larger area for microscopic examination, potentially the entire margin. However, this method does not allow for gross appreciation of the tumor or an accurate assessment of the distance between the lesion and the nearest margin.

gross sectioning best allows for thorough macroscopic analysis including measurement of the distance from the lesion to the nearest surgical margin (e-Fig. 10.8). The selected area for frozen section analysis should be visually closest to the margin. Parallel or en face sectioning does provide a larger area for microscopic examination, potentially the entire margin. However, this method does not allow for gross appreciation of the tumor or an accurate assessment of the distance between the lesion and the nearest margin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree