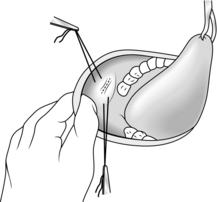

28 Exploration of the lower pole of the parotid Operations on the parotid duct orifice in the mouth Removal of stone from the submandibular duct Excision biopsy of a basal cell carcinoma of the face Local excision or biopsy of an intraoral lesion Excision of suprahyoid (submental) cyst Excision of thyroglossal cyst, sinus and fistula Operations for branchial cyst, sinus and fistula Excision biopsy of cervical lymph node Operations on tuberculous cervical lymph nodes Radical parotidectomy with block dissection Radical submandibular sialoadenectomy with resection of segment of mandible and block 1. Discuss likely blood loss with the anaesthetist, who may decide to use hypotensive anaesthesia, lowering the arterial blood pressure by such agents as ganglion blockers. If you do operate under hypotension, remember the increased risk of reactionary haemorrhage shortly after the wound has been closed, so delay closure until you are certain that the blood pressure has been restored to normal. 2. Venous bleeding is more difficult to control than arterial. Venous pressure, and therefore venous bleeding, can be minimized by paying careful attention to posture. Position the patient so that the area being operated on is at a higher level than the heart. Carefully protect local veins from direct pressure resulting from clumsy positioning of the head, neck or shoulders, and the presence of supports or towels, etc. If it is necessary to divide a large vein draining the operative area, postpone this step in the operation to the latest possible moment. The anaesthetist helps to reduce venous pressure by maintaining the clearest possible airway and by keeping arterial carbon dioxide tension normal or below normal. 3. Control blood vessels before dividing them; in this way you obviate excessive blood loss from, for example, a haemostat slipping off the cut vessel. For sizeable vessels, pass two ligatures with an aneurysm needle and tie them around the vessel before dividing the vessel between them. 4. Many surgeons infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissues with a solution of 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) in normal saline, thereby producing vasospasm and reducing bleeding. 5. Diathermy is a valuable aid to haemostasis, but use it carefully. It stops bleeding by coagulating the tissues at more than 1000°C, potentially causing extensive destruction. Cutting diathermy produces high-intensity energy over a small sphere from the active electrode; coagulating current produces a lower intensity over a larger sphere. It is traditional to use the cutting current to incise tissues and the coagulating for producing haemostasis, on the principle that the larger zone of action of the coagulating current compensates for any small inaccuracy in identifying the bleeding point. Use the cutting current for haemostasis, having first made sure that each bleeding point has been accurately identified; this discipline reduces unnecessary tissue destruction to a minimum. 6. After the operation, use suction drainage to obliterate the dead space under the skin flaps, thereby reducing the risk of secondary haemorrhage and haematomas. Note that in the neck a haematoma is a potentially lethal complication, because of its possible effect upon the patency of the airway. 1. Before operation, ensure that every patient has been asked about any history of a bleeding tendency, that a haemoglobin estimation has been performed and that blood has been taken for grouping and serum saved in case cross-matching becomes necessary. 2. With regard to which cases require blood to be cross-matched before the operation, it is difficult to lay down rules. Much depends upon your experience and that of the anaesthetist. Blood transfusion is rarely necessary for conservative parotidectomy under good hypotensive anaesthesia, but, if you are an inexperienced operator, working with normotensive anaesthesia, have 2 units of blood cross-matched and have 4 units cross-matched before an extensive resection involving bone and/or block dissection of the cervical lymph nodes. 3. Normally, the anaesthetist controls blood replacement during the operation. The principles are accurate measurement of the blood loss by weighing swabs and measuring the volume of the contents of the sucker bottle, with prompt and complete replacement, preferably monitored by the measurement of central venous pressure or of urine output. 1. Assess a parotid lump before operation by careful clinical examination. Pain and facial nerve palsy are diagnostic of malignancy unless tuberculosis is suspected. Fine-needle aspiration cytology is accurate in about 85% of cases,2 but the role of needle biopsy is debatable. Small discrete masses usually require surgical rather than conservative management.3 Most parotid neoplasms are benign.4 2. The facial nerve and its five main branches run through the substance of the parotid gland and are at risk in parotidectomy. 3. Plan to expose the facial nerve and its branches at an early stage of any parotidectomy and over a sufficiently wide area to ensure that the required resection is achieved without cutting the nerve (conservative parotidectomy). However, if the object of your operation is to remove a lump in the parotid with a wide margin of normal tissue, you will sometimes find that this condition is impossible to fulfil; an adequate margin cannot be achieved unless you sacrifice the whole nerve (radical parotidectomy) or one or more of its branches (semi-conservative parotidectomy).5 4. If the decision is not clear-cut whether to sacrifice the main nerve, lean towards radicalism in elderly males, conservatism in young females. Biopsy the lump, and ask for an immediate histological opinion on frozen sections, provided: 5. Repair any gap you produce in the facial nerve system by immediate primary suture, if possible, or by bridging the defect with a free cable graft, taken as a routine from the great auricular nerve at the beginning of the operation. Ignore any damage to the fifth (cervical) branch. 6. Operations for recurrent parotitis not due to parotid calculus (i.e. the group of conditions known as Sjogren’s or sicca syndrome) may require total conservative parotidectomy. 1. If you confirm a malignant tumour, discuss the implications with the patient, especially if there is a prospect of sacrificing part or all of the facial nerve. 2. Check that male patients are clean-shaven on the side of the tumour. 3. Have the patient lying near your side of the operating table. Tilt the top half of the operating table upwards until the external jugular vein collapses. Extend the patient’s head on the neck, turn it away from you and place it on a head-ring to stabilize it, with a sandbag, or similar, under the shoulder 4. To protect the patient, and protect yourself from charges of negligence, monitor the facial nerve. Insert needle electrodes into the ipsilateral frontalis and mentalis muscles to record electromyographic signals from them, producing audible and visual signals when the facial nerves supplying them are stimulated. The nerve monitor can also be used as an aid to identify a doubtful nerve or to confirm that the nerve is intact by demonstrating a signal on stimulating the nerve. 5. Ensure that the patient’s eyes are protected from possible damage by lotions used in the skin preparation. Clean the skin over the area shown in Figure 28.1. 6. Place the towels to leave exposed only the area shown in Figure 28.1. Push some ½″ ribbon gauze (which is added to the swab count) into the external auditory meatus with a pair of artery forceps and then discard them. 7. Ask the anaesthetist to maintain the patient in hypotension if possible. 1. Follow the standard S-shaped cervicomastoid-facial incision (Fig. 28.1). The lower, cervical part lies in the upper skin crease of the neck, extending forwards to the external jugular vein. The upper, facial, part lies in the skin crease at the anterior margin of the auricle, extending upwards to the zygoma. Between these two parts, the mastoid part of the incision curves gently backwards over the mastoid process. If you intend to remove a lump in this area, exaggerate the posterior curve to encompass the lump. Make the incision in three parts from below upwards, stopping all bleeding before proceeding to the next part. In this way you avoid bleeding from the upper part of the wound obscuring your field lower down. 2. Start by making the cervical part of the incision. Incise skin, fat and platysma. 3. Identify the external jugular vein near the anterior end of the wound, and two branches of the great auricular nerve vertically below the anterior margin of the auricle (Fig. 28.2). Preserve the vein but sacrifice the thinner, usually more anterior, branch of the nerve. Dissect free but do not yet excise, about 4 cm of the thicker branch of the nerve.7 The nerve runs upwards towards the ear and breaks up into two or three branches; if possible, include a centimetre of each branch with the segment of stem excised. 4. Facilitate the dissection by placing a row of artery forceps on the subcutaneous fat of the upper margin of the wound. Have your first assistant, standing opposite you, to lift the forceps. Identify the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle. Follow the border upwards and posteriorly towards the mastoid process, as far as the incision permits. Deepen the dissection to expose in turn the posterior belly of the digastric and the stylohyoid muscles, proceeding at this stage only as far as is convenient. 5. Perform the mastoid part of the incision and deepen it on to the sternomastoid muscle. Continue to expose the anterior border of the muscle right up to the mastoid process. Place more artery forceps on the upper subcutaneous border of the wound and have your assistant pull the superficial part of the lower pole of the parotid gland forwards from the anterior border of the sternomastoid. Friable, yellow parotid tissue forms the visible aspect of the anterior margin of the incision. 6. Continue to expose the posterior belly of the digastric and the stylohyoid muscles upwards towards the mastoid process as far as is convenient at this stage. 7. Create the facial part of the incision and deepen it along the anterior surface of the cartilaginous external auditory meatus by pushing in an artery forceps and opening the blades in an antero-posterior plane. Deepen this plane until you can feel the junction between the cartilaginous and bony external auditory meatus (Fig. 28.2). 8. You now have a large S-shaped incision in which two deep cavities, one in the neck and one in front of the ear, are separated by a bridge of tissue where the dissection has not been deepened to the same extent, in front of the mastoid process. Whittle away these tissues piecemeal; push a closed, curved artery forceps from the upper cavity downwards at 45° towards the lower cavity so that the tips emerge. Separate the tips of the artery forceps and cut the tissue between them. Concentrate on defining the region where the anterior border of the sternomastoid and the two deeper muscles reach the anterior surface of the mastoid process. The dissection approaches the region of the facial nerve, so take increasing care. Remove smaller bites of tissue. Have the diathermy apparatus turned to the lowest mark. 9. The signal that you are close to the facial nerve is to identify the stylomastoid artery running downwards and forwards in the same general direction as the facial nerve. Control it with ligatures or with diathermy coagulation and divide it. Continue the dissection and about 3 mm deeper you will find the facial nerve trunk. It is 3–6 mm in diameter, white but with fine red vessels visible on its surface, and it bifurcates 1–2.5 cm below the base of the skull. 10. Further steps depend upon the exact operation you wish to perform. 1. You cannot determine clinically that a lump in the parotid gland is confined to the superficial part, so cannot determine beforehand to perform a superficial parotidectomy. 2. The definite indication for superficial parotidectomy is therefore recurrent parotitis from a stone in the parotid duct at a site inaccessible from the mouth.8 3. You must remove as much parotid tissue and as long a length of parotid duct as you can reasonably achieve, otherwise there is a risk of recurrent flare-up of the residual infected tissues. 1. Choose either the upper or the lower main division of the nerve to start the dissection, whichever seems the most convenient. Aim to reflect forwards the parotid tissue superficial to the facial nerve and its five branches until you reach the anterior margin of the gland. 2. Place the closed blades of fine, gently curved mosquito forceps, concavity superficial, along the exposed division of the nerve and in contact with the nerve. 3. Push the forceps points along the surface of the nerve for about 5–10 mm into the region where the nerve is still unexposed (Fig. 28.3). 4. Parotid tissue is tough, requiring a surprising amount of force to split it. Separate the points of the artery forceps and elevate the whole instrument to tauten the overlying tissue bridge. Divide the bridge with scissors, exposing a further few millimetres of the nerve. 5. Repeat the manoeuvre, following the more posterior nerve at any bifurcation. You eventually reach beyond the margins of the parotid gland – at the zygoma if you have followed the upper division, beyond the external jugular vein if you have followed the lower division. 6. Repeat the process with the other main division of the facial nerve and its most posterior branch. You have now exposed the facial nerve trunk and its temporal and cervical branches. 7. The zygomatic branch arises from the upper division, the mandibular from the lower division, and there are at least two buccal branches, one from each division, and sometimes a third, usually from the lower division. Working from the periphery towards the centre of the gland, follow the other main nerve branches forwards to the anterior margin of the parotid gland, that is along a vertical line halfway between the anterior and posterior borders of the masseter muscle. 8. Reflect the skin from the anterior flap until you reach the superior and anterior margins of the gland. With a little more dissection along the nerve branches you will free the gland except for the parotid duct. 9. Dissect the parotid duct forwards to the anterior border of the masseter muscle, where it turns medially to perforate the cheek and reach the mouth. Free from it the closely applied buccal nerve branches, then tie the duct at the anterior border of the masseter with an absorbable suture and cut the duct. The excision is complete. 1. Has the anaesthetist raised the blood pressure to normal for the patient or at least greater than 100 mmHg? If not, you risk a high incidence of reactionary haemorrhage. Restore the table to the horizontal position to ensure that any tendency to bleeding becomes immediately manifest. You can ask the anaesthetist to perform a Valsalva manoeuvre to check for any bleeding points. 2. Have you removed the ribbon gauze from the external auditory meatus? 1. Most lumps in the parotid region are parotid tumours, and most of the tumours are benign adenomas.9 Also, most lumps are clinically unremarkable, that is they present no features that enable you to distinguish between non-neoplastic, neoplastic benign and neoplastic malignant lumps.10 The well-recognized ability of adenoma cells to implant if shed into the wound renders a preliminary open biopsy inadvisable. However, fine-needle aspiration cytology does not seem carry an associated risk of implantation. 2. Controversy besets the decision as to whether to remove the lump with a wide margin of normal tissue after exposing and protecting the facial nerve, or whether to enucleate the lump in the hope of preserving the nerve. The available evidence suggests that enucleation does not reduce the incidence of permanent damage to the facial nerve and that the incidence of recurrence after enucleation and radiotherapy is unacceptably high.1 Standard management in the UK, the universal management in the USA, is for excision of an unremarkable lump with the widest possible margin of normal tissue, with exposure and preservation of the facial nerve unless the tumour is invading it, or a branch of it. In this case the lump is malignant, so sacrifice the nerve element. 1. Employ the cervicomastoid-facial S-shaped incision. 2. Expose the main trunk of the facial nerve and, if possible, its primary bifurcation. Dissect forwards along the nerve or along its upper and lower divisions. It is soon evident whether the lump is in the part superficial to the facial nerve, or deep to the nerve, and whether the nerve trunk or main divisions run into the lesion rather than being pushed aside by it. 1. Dissect under the trunk, divisions and branches of the facial nerve. With a nerve hook and some nylon ribbon, gently lift the nerves off the underlying deep part of the parotid gland until there is clear space between the nerves and the whole of the deep part of the gland. 2. Identify the external carotid artery and companion vein if there is one, at the upper border of the stylohyoid muscle. Ligate and divide the artery and companion vein. 3. Mobilize the deep part of the parotid and its contained lump by working from the anterior and posterior parts of the gland towards the centre and from its lower pole upwards. Aim to mobilize the deep part so as to remove it above or below the facial nerve system, or between the two main divisions in the region of the bifurcation, whichever is most convenient (Fig. 28.4). 4. Facilitate mobilization of a lower pole containing a large tumour by dividing the stylomandibular ligament, of which the anterior insertion is into the angle of the jaw. If necessary, fracture the styloid process to gain more room. 5. Continue to mobilize the deep parotid off the masseter muscle and mandible anteriorly, and the bony external auditory meatus posteriorly. As you approach the upper part of the gland, identify the termination of the external carotid artery at the upper pole where it bifurcates into the superficial temporal artery and the maxillary artery. Tie to divide these arteries and their accompanying veins. The deep parotid is now free and you can remove it. 1. Reflect the skin forwards to the anterior margin of the gland. 2. Find the external carotid artery at the lower pole of the gland and divide this and its companion vein between ligatures. 3. Divide the trunk of the facial nerve and mobilize the posterior aspect of the whole gland off the cartilaginous and bony external auditory meatus. 4. Divide the facial nerve branches at the anterior border of the gland and mobilize the whole gland backwards off the masseter muscle and the posterior border of the mandible. 5. Mobilize the whole gland from below upwards. Doubly ligate and divide the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries at the upper pole of the gland and remove the freed whole gland with its contained facial nerve system. 6. A semi-conservative parotidectomy may be performed, sacrificing one or more branches of the facial nerve but preserving at least one of the upper four branches, to preserve an adequate margin round the lump. Repair the cut branches end-to-end if the cut ends will meet; otherwise bridge the gap or gaps using the segment of greater auricular nerve you obtained earlier, with the finest available suture material (usually 8/0 or 10/0). 1. Hobsley M. A Colour Atlas of Parotidectomy. London: Wolfe Medical Publications; 1983. 2. Al-Khafaji BM, Nestok BR, Katz RL. Fine-needle aspiration of 154 parotid masses with histologic correlation: a 10 year experience at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer 1998;84:153–9. 3. McGurk M, Hussain K. The role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the management of the discrete parotid lump. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1997;79:198–202. 4. Hibbert J, editor. Laryngology and head and neck surgery. In: Scott Brown’s Otolaryngology, vol. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. 5/20, page 6. 5. Stevens KL, Hobsley M. The treatment of pleomorphic adenomas by formal parotidectomy. Br J Surg 1982;69:1–3. 6. Hobsley M, Thackray AC. Salivary glands. In: Hadfield JG, Hobsley M, Morson BC, editors. Pathology in Surgical Practice. London: Edward Arnold; 1985, p. 22–34. 7. Christensen NR, Jacobsen SD. Parotidectomy: preserving the posterior branch of the greater auricular nerve. J Laryngol Otol 1997;111:556–9. 8. Suleiman SI, Thomson JPS, Hobsley M. Recurrent unilateral swelling of the parotid gland. Gut 1979;20:1102–8. 9. Hobsley M. Salivary tumours. Br J Hosp Med 1973;10:553–62. 10. Hobsley M. Sir Gordon Gordon-Taylor: two themes illustrated by the surgery of the parotid gland. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1981;63:264–9. 1. The exploration may be used to determine if a lump in the neck is or is not in the lower pole of the parotid gland. The lower pole of the gland extends well down into the neck behind the angle of the jaw and is separated anteriorly from the submandibular salivary gland only by a thickened sheet of fascia, the stylomandibular ligament. 2. The procedure can be employed to obtain a large piece of tissue from the gland for histological examination. 1. Make the incision in the upper skin crease of the neck, starting just in front of the external jugular vein, extending backwards to a point vertically below the lowermost tip of the mastoid process. 2. Identify the external jugular vein and expose the two divisions of the greater auricular nerve. Sacrifice the thinner division of the nerve. Mobilize the thicker division, but preserve it for the moment; you may sacrifice the thicker division later. 3. Define the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle. Place a row of artery forceps on the subcutaneous fat of the upper margin of the wound and have your assistant raise this edge off the muscle. 1. If the lump is in the parotid, continue the operation as a parotidectomy for a lump. Even if the lump seems very superficial, do not be tempted to excise it locally. To safeguard the facial nerve and ensure complete removal of the lump, you must carry out a formal parotidectomy after exposing the trunk of the facial nerve. 2. If the lump is not in the parotid, remove the lump, leaving the parotid untouched. 3. If you aim to take a generous biopsy of the parotid, undertake step 1 in Access above. Deepen this cervical part of the dissection to expose the posterior belly of the digastric and the stylohyoid muscle. Define these muscles up to the region of the mastoid process. 4. You will find that a large portion of the lower pole of the parotid gland is now elevated with the anterior skin flap. You can remove a large biopsy of this mobilized portion without risk to the facial nerve. 1. Stomatoplasty (Greek: stoma = mouth + plassein = to form or reform) is used to enlarge the parotid duct orifice,1 either to enable a calculus in the parotid duct to be passed more easily or to prevent a stricture forming at the orifice after the duct has been explored, for example to remove a stone from the duct. 2. Two branches of the facial nerve are closely applied to the parotid duct in the cheek and may even wind around the duct. Therefore, do not pass ligatures round the duct to prevent a stone from escaping or to assist retraction; contrast this with the procedure for removal of stone from the submandibular duct. 1. Ask the anaesthetist to use a per-nasal endotracheal tube, thereby leaving the mouth free for your manipulations. Also ask him to pack the pharynx around his tube, as a precaution against blood from the mouth being aspirated into the lungs. 2. Fix the patient’s mouth open with a dental prop or Ferguson’s forceps inserted between the teeth or gums of the jaws on the side opposite to your operation. Place a strong silk suture into the tip of the tongue and have your assistant use it to retract the tongue towards the opposite side. 3. Identify the papilla on which the parotid duct opens on the inside of the cheek, immediately opposite the second upper molar tooth. Take an atraumatic 2/0 absorbable synthetic stitch on a half-circle (30 mm) cutting needle and put a stitch into the mucosa and underlying muscle of the cheek, about 5 mm above the papilla. Do not tie this stitch; cut it so that each end is 15 cm long, and grip the ends of the stitch with a pair of artery forceps (Fig. 28.5). 4. Insert a similar stitch about 5 mm below the papilla. Have your assistant pull on the two stitches, thereby elevating the region of the papilla towards you. 1. Feel the region of the papilla with two fingers of one hand, exerting counter-pressure with the fingers of the other hand applied to the external aspect of the cheek. Can you feel a stone? 2. Identify the parotid duct orifice using a lacrimal duct dilator, which is a fine probe with a slight bend at each end in the shape of an elongated letter ‘S’. To facilitate this manoeuvre, use one hand to guide the dilator and, with the other, pull the angle of the mouth forwards towards you with your thumb working against the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of your index finger, and push the cheek inwards with the fingertips. 3. At this stage, you are ready to remove a stone from the parotid duct, or to proceed immediately to stomatoplasty, as indicated by your findings. 1. If you can feel the stone at the orifice, keep the papillary region pushed inwards into the mouth by the manoeuvre just described and cut down on the stone with a short-bladed, long-handled scalpel. Start the incision at the orifice of the duct and carry it horizontally backwards for 1 cm. 2. When you have deepened the incision sufficiently, the stone becomes visible. Grasp it with fine-toothed dissecting forceps, and lift it out of the duct. You will find that your incision has divided two layers of mucosa, the lining of the inside of the cheek and the inner lining of the wall of the parotid duct. 3. If you cannot feel a stone in the duct, pass the lacrimal duct dilator into the orifice and along the duct for 2 cm. Get your assistant to hold the dilator steady, keep the papillary region of the cheek pushed inwards into the mouth with your other hand and cut down on the dilator, carrying the incision from the orifice of the duct horizontally backwards for 1 cm. 4. Explore the duct as far back as possible by passing the lacrimal duct dilator. You may be able to feel a stone grating on the tip of the probe. If you do, try milking the stone forward by digital pressure on the parotid gland and duct from outside. This manoeuvre is not often successful, but is worth trying. 5. Whether or not you found and removed the stone, complete the operation by fashioning a large parotid duct orifice. You will find that your incision has divided two layers of mucosa, the lining of the inside of the cheek and the inner lining of the wall of the parotid duct. Unite these two layers with a series of interrupted, 3/0 absorbable synthetic sutures around the margins of the incision (Fig. 28.6). 1. Make sure all bleeding has stopped. 2. Remove the stay sutures above and below the duct orifice and the suture from the tongue, and check that bleeding does not continue from the puncture wounds. 3. Ask the anaesthetist to remove the pharyngeal pack. If the pack has been effective, there will be no blood on the deeper part of the pack.

Head and neck

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Details of anatomy tend to be more important in the head and neck than in other regions. Numerous structures are crowded into a small volume and many of them, such as the facial nerve, perform important functions. Some are vital to life itself, such as the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the internal carotid artery. Refresh your memory of the local and neighbouring anatomy before performing a new or unfamiliar operation. Before embarking on any major procedure consider seeking advice from, or collaborating with, a plastic, thoracic, dental or neuro-surgeon or otolaryngologist.

Details of anatomy tend to be more important in the head and neck than in other regions. Numerous structures are crowded into a small volume and many of them, such as the facial nerve, perform important functions. Some are vital to life itself, such as the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the internal carotid artery. Refresh your memory of the local and neighbouring anatomy before performing a new or unfamiliar operation. Before embarking on any major procedure consider seeking advice from, or collaborating with, a plastic, thoracic, dental or neuro-surgeon or otolaryngologist.

The airway may be threatened by the accumulation of blood, by laryngospasm, etc., so insist on endotracheal intubation for all but the simplest procedures.

The airway may be threatened by the accumulation of blood, by laryngospasm, etc., so insist on endotracheal intubation for all but the simplest procedures.

Gastrointestinal complications such as peritonitis, paralytic ileus and disturbances of water and electrolyte balance are rare, as is thrombo-embolism.

Gastrointestinal complications such as peritonitis, paralytic ileus and disturbances of water and electrolyte balance are rare, as is thrombo-embolism.

Postoperative chest complications occur following direct interference with respiratory passages or after long operations but are less common than following abdominal or thoracic surgery.

Postoperative chest complications occur following direct interference with respiratory passages or after long operations but are less common than following abdominal or thoracic surgery.

Even massive resections of tissues are therefore well tolerated. Infection is uncommon and healing is usually by first intention. When skin grafting is necessary to repair a defect, the grafts take well. Good healing is evidence of the good blood supply enjoyed by the territory, the corollary being that the principal operative hazard, after damage to important anatomical structures, is primary haemorrhage.

Even massive resections of tissues are therefore well tolerated. Infection is uncommon and healing is usually by first intention. When skin grafting is necessary to repair a defect, the grafts take well. Good healing is evidence of the good blood supply enjoyed by the territory, the corollary being that the principal operative hazard, after damage to important anatomical structures, is primary haemorrhage.

MINIMIZE BLOOD LOSS

REPLACE BLOOD LOSS

PAROTIDECTOMY

Appraise

You take extreme precautions against spreading the tumour in taking the biopsy: parotid tumours are notorious for their tendency to implant

You take extreme precautions against spreading the tumour in taking the biopsy: parotid tumours are notorious for their tendency to implant

Your pathologist is an expert in the histopathology of parotid lesions.6

Your pathologist is an expert in the histopathology of parotid lesions.6

Prepare

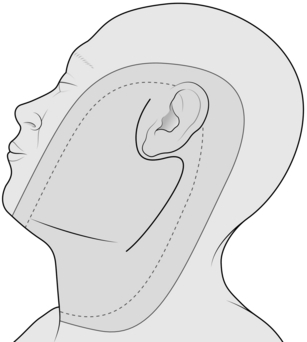

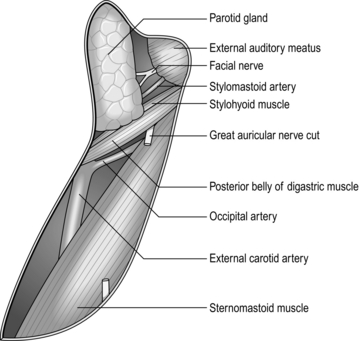

Access

SUPERFICIAL PAROTIDECTOMY

Appraise

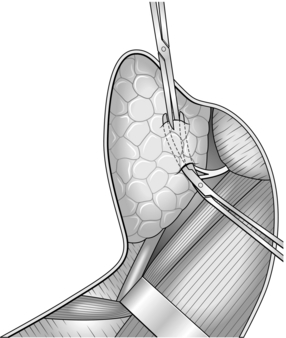

Action

Checklist

PAROTIDECTOMY FOR A LUMP IN THE PAROTID REGION

Appraise

Access

Action

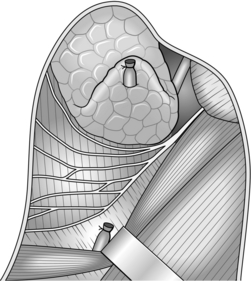

ACTION

REFERENCES

EXPLORATION OF THE LOWER POLE OF THE PAROTID

Appraise

Access

Action

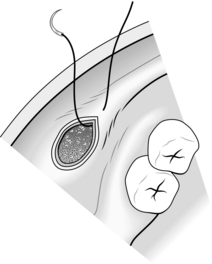

OPERATIONS ON THE PAROTID DUCT ORIFICE IN THE MOUTH

Appraise

Access

Access

REMOVAL OF STONE FROM THE PAROTID DUCT: INTRAORAL APPROACH

Action

PAROTID DUCT STOMATOPLASTY

Closure

Checklist

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Head and neck