Hand Surgery: Traumatic Injuries of the Hand

Kevin C. Chung

Introduction

Traumatic injuries of the hand are common in emergency departments and account for approximately one-fifth of total patient visits each year. Because of the complexity of hand anatomy, treating hand injuries can be daunting for all involved and injudicious treatment often leads to unsatisfactory outcomes and potential litigations. Because of the ubiquity of hand and upper limb trauma, this chapter will present a systematic approach to evaluate the injured hand by presenting the anatomy of the structures involved as well as the relevant examination and treatment concepts.

The precise territory encompassed by “hand surgery” is not clearly defined. In the traditional sense, hand surgery may involve only the hand distal to the wrist joint. However, the current concept of hand surgery territory may extend from the fingertip to the elbow, and even sometimes as far as the shoulder. In this chapter, we will define hand surgery territory as injuries below the elbow.

Traumatic injuries of the hand often occur from laceration or crush accidents. The distinct structures of the hand include the bone, tendon, nerve, blood vessel, joint, and skin. Combined injuries of the hand, with involvement of multiple structures, can be challenging because of the uncertainty of what structures should be treated first. However, understanding the anatomy of the hand will assist in rendering a treatment plan based on a sequential and structured physical examination, rather than haphazard probing of the injured limb. The hand-injured patient is already quite distressed, and the chaos in the typical emergency room does not provide sufficient tranquility to assuage the anxious patient. It is critical that the hand-injured patient is moved into a quiet room where a systematic evaluation of the hand can be undertaken. Table 1 lists some of the do’s and don’ts of assessing a patient with hand injury. Many of these caveats are violated during the initial assessments and frequently lead to inefficient care and consequent consternation for everyone involved. But with some fundamental understanding of hand surgery principles, the hand can be less mystifying. The care of the hand-injured patient starts with the hand examination.

Hand Examination

A comprehensive hand examination does not need to be a tedious exercise, but rather a rapid, sequential examination of the hand and upper limb to understand the extent of injury. For example, a person with a forearm laceration may sustain tendon and nerve injuries. Therefore, based on the functional anatomy concept, the lack of extension of the index and middle fingers may suggest tendon or muscle injuries to these respective structures. Furthermore, lack of sensation over the radial dorsal hand may suggest an injury to the superficial radial

nerve, which supplies the radial dorsal half of the hand.

nerve, which supplies the radial dorsal half of the hand.

Table 1 Do’s and Don’ts of Assessing a Patient with Hand Injury | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

My examination sequence is to evaluate the nerve, tendon, vessel, and the joints, and then obtain plain radiographs of the injured regions of the upper limb to detect potential fractures.

Nerve

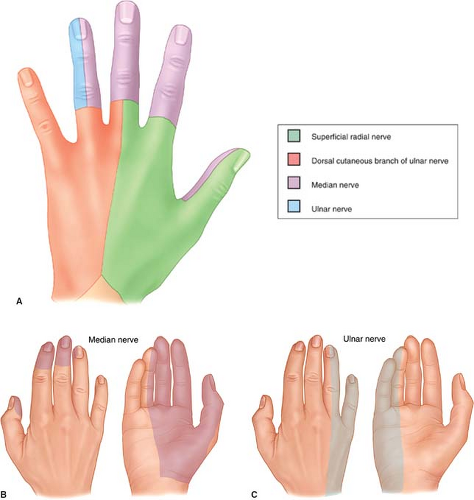

The hand is innervated by three major nerves: the median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Fig. 1A-C). Each nerve provides sensory and motor input to the hand. For example, the radial nerve supplies sensation to the dorsum of the thumb, index, and middle finger, and also gives motor input to all the finger and wrist extensor tendons. There are specific

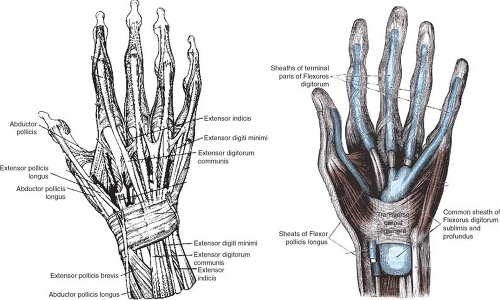

examination findings of nerve territories that indicate the conditions of the nerve involved. For the radial nerve, intact sensation over the dorsum thumb/index webspace indicates the integrity of the radial nerve, or more specifically, the radial sensory nerve (Fig. 2). The ability to extend the thumb when the hand lies flat on a table is powered by the extensor pollicis longus, which is supplied by the terminal branch of the radial nerve, or more specifically, the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve (Fig. 3A-C).

examination findings of nerve territories that indicate the conditions of the nerve involved. For the radial nerve, intact sensation over the dorsum thumb/index webspace indicates the integrity of the radial nerve, or more specifically, the radial sensory nerve (Fig. 2). The ability to extend the thumb when the hand lies flat on a table is powered by the extensor pollicis longus, which is supplied by the terminal branch of the radial nerve, or more specifically, the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve (Fig. 3A-C).

Fig. 2. Examination of integrity of radial sensory nerve by testing sensation of the dorsum thumb/index webspace. |

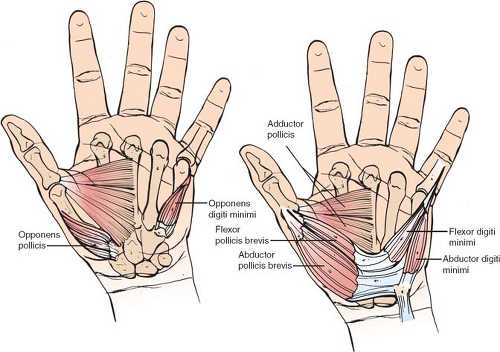

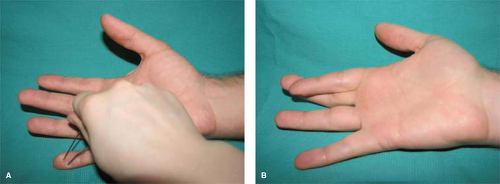

Laceration of the ulnar nerve can produce discrete areas of functional loss that can be predicted based on the location of the laceration. The ulnar nerve is a highly specialized nerve that innervates most of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Intrinsic muscles are muscles that have their origins and insertions in the hand that function to orchestrate the fine movements of the fingers. These intricate, fine muscles of the hand include the interosseous muscles that flex the finger metacarpophalangeal joints and extend the finger interphalangeal joints (Fig. 4). In contrast, extrinsic muscles are muscles that have their origins outside the hand. For example, extrinsic finger flexors such as the superficialis and profundus tendons have their origins over the medial epicondyle at the elbow to produce flexion of the fingers. In the forearm, the ulnar nerve’s motor innervations are only limited to the flexor carpi ulnaris, which flexes the ulnar wrist and the profundus tendons to the ring and little fingers (Fig. 5). The coordination of the ulnar nerve is particularly important because injury to the ulnar nerve paralyzes the interosseous muscles, which balance the flexor and extensor muscle tone, to result in a hand posture known as claw deformity. This deformity is a result of the overpowering of the extensor tendons by the flexor tendons to cause this nonfunctional posture (Fig. 6). In addition, injury to the ulnar nerve also paralyzes the thumb adductor muscle, making it difficult for the patient to grip objects.

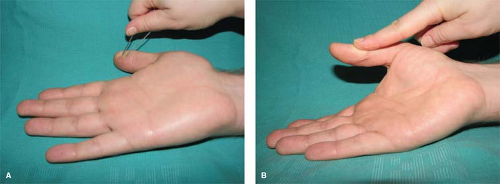

In ulnar nerve examinations, the predictable sensory distribution is over the volar little finger (Fig. 7A). The notable motor exam is the ability to cross the index and middle fingers, which illustrates the function of the ulnar nerve innervating the interosseous muscles (Fig. 7B).

The median nerve provides sensation to the radial hand by sending nerve fibers into the thumb, index, middle, and radial side of the ring finger. It also controls the thenar muscles of the hand as well as most of the finger and wrist flexors. Injury to the median nerve proximal to the wrist not only will result in loss of sensation to the radial hand, but the patient will experience weakness of the thumb because of paralysis of the thenar muscles that powers thumb abduction and opposition. In median nerve examination, the intact sensation over the pulp of the thumb is predictable for sensory nerve function and the ability to abduct the thumb marked by thenar muscle contraction confirms the median motor nerve function proximal to the wrist (Figs. 8A and B).

Tendon

In each finger, there are two tendons that move the fingers, the superficialis and the profundus tendons, and each attaches to the distal aspects of a joint in order to move it. The creases in the fingers and the wrist correspond to joints in which the tendons are attached. For example, the wrist creases are made by wrist flexor and extensor tendons that insert at the base of the metacarpals. In some patients in whom the joints are not developed, finger creases are not present, which reveal that the joint is nonfunctional. The thumb has only one flexor tendon (flexor pollicis longus) that attaches at the interphalangeal joint. However, the thumb is supported by a group of intrinsic muscles at the thenar area, which includes muscles that provide abduction (abductor pollicis) and opposition (opponens pollicis) of the thumb.

A complex arrangement of the extensor tendons of the fingers and wrist lies over the dorsum of the hand. For example, the thumb is controlled by the extensor pollicis longus tendon, whereas the index and the little fingers are controlled by two tendons, the communis tendon (all attached to a single muscle to power all the fingers) and the proprius tendon that gives independent motion of the index and little fingers. The extensor tendons to the hand are interconnected by junctura tendinae that serve to coordinate motion for each finger during finger

extension. The wrist is controlled by three extensor tendons: the extensor carpi radialis longus, brevis, and the extensor carpi ulnaris.

extension. The wrist is controlled by three extensor tendons: the extensor carpi radialis longus, brevis, and the extensor carpi ulnaris.

The examination of the tendons is rather straightforward. The examiner will ask the patient to flex each joint distal to the injury site in order to determine whether a tendon or tendons are cut. For example, an inability to flex the distal interphalangeal joint after a volar finger laceration is a clear indication of a flexor digitorum profundus tendon laceration.