Hairy Cell Leukemia

Definition

A chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of mature B cells with characteristic cytoplasmic projections. The neoplasm typically infiltrates the bone marrow, spleen, and liver with relatively few hairy cells present in the blood.

Synonym

Leukemic reticuloendotheliosis.

Epidemiology

Descriptions of patients with disease that most likely was hairy cell leukemia (HCL) can be found in the literature in the early twentieth century (1), but the disease was clearly characterized as a clinicopathologic entity in 1958 by Bouroncle and colleagues and named leukemic reticuloendotheliosis (2). The term hairy cell was coined by Schrek and Donnelly in 1966 (3). Hairy cell leukemia is the accepted name for this disease and is used in the current World Health Organization classification (4).

Hairy cell leukemia is an uncommon B-cell neoplasm that represents approximately 2% of all leukemias (5). In the United States, the incidence is 0.33 cases per 100,000 person-years, which translates into approximately 600 new cases of HCL per year (2,3). The disease predominantly affects adult men, with a male-to-female of approximately 4:1 and a median age of 55 years (1,4).

Pathogenesis

The cell of origin of HCL was controversial prior to the era of immunophenotyping and molecular genetic analysis. These methods clearly have shown that HCL is a neoplasm of B cells that express B-cell antigens and rearrange their immunoglobulin heavy and light chain genes (6,7,8). Immunophenotypic studies also have suggested that HCL cells are activated and correspond to a later stage of B-cell maturation, but prior to the plasma cell stage. More recent gene expression profiling studies confirm this impression, showing that the profile of HCL is very similar to postgerminal-center memory B cells (9). The current cell of origin of HCL is unknown, but origin from splenic marginal-zone B cells has been suggested by others (10).

Both immunophenotypic and gene expression profiling studies have shown that HCL cells are highly activated, and the cellular mechanisms explaining this activation are becoming known (9,11). Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are activated in HCL. Evidence of activation of both the p38–MAPK–JNK cascade transmitting apoptotic signals and the MAPK kinase-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade transmitting survival signals has been shown. Protein kinase C and Src, which activate MAPK–ERK signaling, are also constitutively activated in HCL. There is evidence of activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)–AKT pathway in HCL, which may explain cyclin D1 upregulation (11). The cells of HCL also produce both basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and the bFGF tyrosine kinase receptor (bFGFR1), allowing for a possible autocrine bFGF–FGFR1 loop involved in oncogenesis (9,11). The bFGF also may be involved in the bone marrow fibrosis characteristic of HCL. The bFGF probably stimulates HCL cells to secrete fibronectin, via interaction of the neoplastic cells with hyaluronan in the bone marrow and CD44 (12).

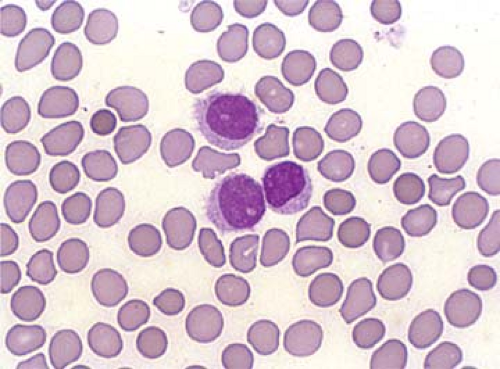

The characteristic hairy cells display elongated cytoplasmic processes (filopodia) if observed via phase-contrast microscopy (3). These “hairs” can also be seen by light microscopy using oil immersion although the processes are less prominent and inconstantly observed using this method (Fig. 62.1). The filopodia are an intrinsic property of hairy cells, because they are retained during in vitro cell cultures even after several days (11). The surface of hairy cells is also dynamic, constantly changing when viewed in phase-contrast microscopic studies (12). The pathogenesis of the filopodia in HCL is currently incompletely understood. HCL cells overexpress polymerized actin (F-actin) at their cell periphery, which is thought to support the filopodia. The protein pp52 (also known as LSP1) is a leukocyte-specific intracellular phosphoprotein that binds to F-actin. pp52 is also overexpressed in HCL cells and is likely involved in the formation or maintenance of the cytoplasmic processes (13,14). Gene expression profiling has suggested that a number of other genes may be involved in the maintenance of the “hairy” phenotype including members of the Rho family of small GTPases, growth arrest–specific 7 (GAS7), CD9, and EPB4.1 (11). Rho GTPases are constitutively activated in HCL, via activation of the MAPK–ERK pathway, and are involved in the formation of filopodia in various cell types (14). GAS7, CD9, and EPB4.1, also overexpressed in HCL cells, bind to or colocalize with F-actin and may play a role in the formation of filopodia (11).

The results of gene expression profiling also provide clues to the distribution of disease in patients with HCL. A number of cell adhesion receptors are overexpressed in HCL cells. Overexpression of α4β1, α5β1, αxβ2, αvβ3, αεβ7, and CD44 has been shown (9,12). Several matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (TIMP1, TIMP4, and other molecules) are also expressed. In aggregate, expression of these molecules most likely contributes to the tendency of HCL cells to involve the bone marrow, liver, and spleen (9,11,12). Hairy cell leukemia cells also underexpress chemokine receptors (e.g., CXCR5 and CCR7) and adhesion molecules (e.g., L-selectin) that are involved in the migration of cells to lymph nodes, possibly explaining the relative infrequency of peripheral lymphadenopathy in patients with HCL (9,11,12).

Clinical Syndrome

The clinical presentation of patients with HCL has evolved since the initial report by Bouroncle and colleagues (2). In earlier studies, the diagnosis was established later in the disease course when the tumor burden was greater (2,15,16). Hepatosplenomegaly was often extreme, lymphadenopathy occurred in up to one-third of patients, visceral involvement was not uncommon, and complications of cytopenias were more

common and pronounced. Infectious complications were also common, in over one-half of patients at some point during their illness (2,15,16,17). The disease is currently detected earlier in its clinical course, when tumor burden is much lower. This can be attributed to increased clinical awareness and improved pathologic diagnosis and the use of flow cytometry immunophenotyping, as HCL has a distinctive immunophenotype allowing detection of very low levels of disease in blood.

common and pronounced. Infectious complications were also common, in over one-half of patients at some point during their illness (2,15,16,17). The disease is currently detected earlier in its clinical course, when tumor burden is much lower. This can be attributed to increased clinical awareness and improved pathologic diagnosis and the use of flow cytometry immunophenotyping, as HCL has a distinctive immunophenotype allowing detection of very low levels of disease in blood.

Hairy cell leukemia is primarily a disease of middle-aged men. In a large study of 725 cases of HCL from Italy published in 1994, the male-to-female ratio was 3.9:1, and the mean age was 54 years (range, 23 to 85 years) (18). Patients with HCL usually have an indolent clinical course. The disease may be detected following the incidental detection of cytopenias, or patients may present with symptoms attributable to cytopenias, such as fatigue and weakness. A subset of patients present with moderate weight loss, fever, or abdominal pain resulting from marked splenomegaly (4,18). Approximately 10% to 25% of patients are asymptomatic at time of diagnosis (1,4,18).

The major physical findings in patients with HCL are splenomegaly in 80% to 90%, hepatomegaly in 50%, and petechiae and ecchymoses in 33%. Splenomegaly can reach massive proportions (up to approximately 4.5 kilograms) and frequently contributes to the cytopenias patients experience (15,16,19). In the Italian study (18), the size of hepatosplenomegaly decreased over the study interval, consistent with earlier detection of disease. Peripheral lymphadenopathy is uncommon in HCL patients and is usually not prominent (18). Lymphadenopathy in HCL patients also is decreasing in size and frequency as the disease is being recognized at earlier stages. In older studies, peripheral lymph nodes were involved at the time of diagnosis in 25% to 35% of cases, and were usually slightly or moderately enlarged (15,16). More recently, the frequency of lymph node involvement at initial diagnosis is usually less than 10% (18). Even when peripheral lymph nodes are not enlarged, however, splenic hilar lymph nodes are commonly involved, and other internal lymph nodes may be involved by HCL (19,20). In an autopsy study by Vardiman and colleagues (21), retroperitoneal, abdominal, and mediastinal lymph nodes were commonly involved by HCL, even when peripheral lymphadenopathy was absent. Rarely, lymphadenopathy can be marked (22). The clinical significance of this occurrence is uncertain, but may be related to transformation to a higher-grade process. Visceral involvement (lungs, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, kidneys, and adrenal glands) can also occur in a subset of HCL patients, usually in patients with high tumor burden, and unusual sites can be involved, including the meninges, bone (lytic lesions), pleura, and skin (23).

Laboratory studies commonly show cytopenias, with 50% to 75% of patients having pancytopenia (1,4,18). Neutropenia is often more severe and out of proportion to the degree of anemia and/or thrombocytopenia. Monocytopenia is a distinctive feature usually present in HCL patients and is a helpful clue for diagnosis (24). Hairy cell leukemia cells can be identified in the peripheral blood smears of most patients, but these cells are usually not numerous (1,4). The bone marrow is commonly involved by HCL; however, bone marrow aspiration often yields a “dry tap” because the neoplasm induces bone marrow fibrosis. Bone marrow biopsy is usually needed to assess the extent of bone marrow involvement (1,4,18,25). A small subset of HCL patients has a small monoclonal paraprotein (1,4). Autoimmune phenomena also are reported rarely in HCL patients, including autoimmune hemolytic anemia, lupus-type anticoagulant, antinuclear antibodies, and other rare syndromes (23,26). Hypocholesterolemia is common in HCL patients and resolves after therapy; the mechanism is unknown (27).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree