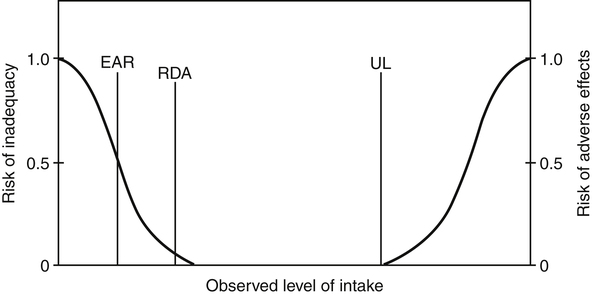

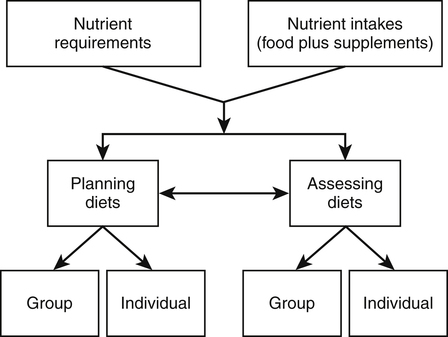

This chapter explores various types of dietary recommendations, ranging from those focused on specific nutrients to those based on entire food groups. In the United States these include the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Patterns. Many other countries around the world have developed their own sets of recommended dietary intakes, dietary guidelines, and/or food guides. In addition, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) of the United Nations system routinely establish recommendations for nutrient intake (FAO, 2009, 2010). Both professionals and consumers can use these recommendations and guidelines in the promotion and selection of healthful diets. In the United States the DRIs are the current reference values for recommended intakes and safe upper levels of intake of nutrients. The term DRI was introduced in 1994 and superceded the former term, Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), which had been the standard since 1941. The DRIs were developed jointly by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), which is the health arm of the National Academies in the United States, and the Canadian government. The DRIs have replaced Canada’s previous reference values known as Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNIs) (IOM, 2006). In contrast to the previous RDAs and RNIs, which provided single values for each nutrient, the DRIs are a set of reference values. DRIs were developed to address some of the limitations of having only a single set of reference values for applying dietary recommendations to individuals and groups. They were developed using a risk assessment framework that considers not only the relationship between nutrient intakes and indicators of adequacy, but also the potential reduction in the risk of chronic disease. The framework also considers the potential health problems from intakes that are too high. The DRIs were issued as a series of reports, with each report covering a group of related nutrients (IOM, 1997, 1998, 2000a, 2001, 2002, 2004). • Calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride • Thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline • Vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids • Vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc • Energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids A selective summary of these reports has also been published, which serves as a more accessible and compact reference for professionals (IOM, 2006). In late 2010 a new DRI report was issued for vitamin D and calcium after it was determined there were sufficient new data to justify reviewing and updating the original DRIs for these two nutrients (IOM, 2011). • EAR: the average daily nutrient intake level that is estimated to meet the requirements of half of the healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group (IOM, 2006, p. 8). In the case of energy, an Estimated Energy Requirement (EER) is provided. • EER: the average dietary energy intake that is predicted to maintain energy balance in a healthy adult of a defined age, gender, weight, height, and level of physical activity consistent with good health (IOM, 2006, p. 8). • RDA: the average daily dietary nutrient intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97% to 98%) healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group (IOM, 2006, p. 8). • AI: the recommended average daily intake level based on observed or experimentally determined approximations or estimates of nutrient intake by a group (or groups) of apparently healthy people that are assumed to be adequate; used when an RDA cannot be determined (IOM, 2006, p. 8). • UL: the highest average daily nutrient intake level that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population. As intake increases above the UL, the potential risk of adverse effects may increase (IOM, 2006 p. 8). • AMDR: the range of intakes of an energy source that is associated with a reduced risk of chronic disease, yet can provide adequate amounts of essential nutrients (IOM, 2006, p. 11). Figure 3-1 shows how the DRI values relate to the risks of either inadequacy or adverse effects. The DRIs provide a set of reference values for 12 life-stage groups for the United States and Canada. Similar sets of recommendations, typically called recommended dietary intakes, exist for other countries or in some cases for a worldwide audience (FAO/WHO, 2002, 2004). The first edition of the Recommended Dietary Allowances, published by the National Academy of Sciences in 1943, provided recommended intakes for energy and nine essential nutrients. The RDAs were revised periodically based on new scientific knowledge and interpretations. With each revision there were changes in the numbers of nutrients considered and the levels recommended, but the basic philosophy was to define RDAs as levels sufficient to cover individual variations and provide a margin of safety above minimum requirements (IOM, 1994). In contrast, the criteria used to determine the DRIs goes beyond preventing a nutrient deficiency disease and also includes optimizing health, reducing the risk of chronic disease, and avoiding overconsumption of a nutrient (IOM, 2006). For example, the DRI for vitamin C is higher than simply the amount to prevent scurvy. It also considers the amount needed for antioxidant protection and tissue saturation while at the same time minimizing urinary loss. Like the former RDAs, the DRIs apply to the healthy general population and are not intended to apply to people who have an acute or chronic disease or who are already malnourished. Other countries with recommended dietary intakes have also debated how to define their levels—should they use a minimal amount that prevents deficiency disease in all healthy people, an intermediate amount that allows for a large margin of safety, or a level that supports optimal nutrition? For example, when setting the requirement for vitamin C, Australia and New Zealand considered several criteria, including biochemical indices, clinical outcomes, vitamin C turnover, and interactions with other protective phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables. Going on the strength of the evidence, the final recommendation was set based on the prevention of scurvy, vitamin C turnover, and biochemical indices of vitamin C status, such as in plasma, urine, and leukocytes. However, it was not based on the potential interaction with other food components eaten at the same time (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2006). The use of professional judgment and interpretation to set an RDA, DRI, or other recommended intake is illustrated by the range of values for some nutrients in sets of standards in different countries. For example, a review of nutrient requirements for children in 29 European countries found a twofold to fourfold difference among countries in their established reference values for vitamin and mineral requirements (Prentice et al., 2004; Pavlovic et al., 2007). Although different standards may be due in part to biology, much of the difference can be explained by the varied approaches used in setting the standards. The IOM has examined the conceptual framework used to develop the DRIs and has identified ways the development process could be enhanced (IOM, 2008). The various DRI values relate to the distribution of requirements and the distribution of intakes, and they can be used to both assess and plan diets of individuals and groups. Dietary assessment is done to determine if the nutrient intake of an individual or group meets their nutrient requirement. Dietary planning is used to recommend a diet that provides adequate, but not excessive, levels of nutrients for either an individual or a group (IOM, 2006). Figure 3-2 provides the conceptual framework for these uses, although using the DRIs to assess and plan diets of individuals is more challenging because the exact nutritional requirements of an individual cannot be readily determined. Both nutrient requirements and nutrient intakes are only estimates based on available data, so any assessment results or dietary recommendations are at best approximations. Nutrient intake data should be considered in the context of other data, such as clinical, biochemical, or anthropometric information. Over the years, the former RDAs were often inappropriately interpreted as the amounts of essential nutrients a healthy individual needs over time. They were also used for several other purposes, including establishing nutrient standards for food assistance programs such as the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program, evaluating dietary survey data, designing nutrition education programs, developing and fortifying food products, and setting standards for food labels (IOM, 1994). The DRIs were purposely developed to address some of the limitations and inappropriate applications of the former RDAs in assessing and planning diets. In general, EARs are used to assess intakes of both individuals and groups. If no EAR exists, the AI can be used in a limited way to assess intakes of individuals and groups. EARs can also be used for planning nutrient intakes of groups. RDAs should only be used as a guide for planning nutrient intakes of individuals. If no EAR (hence no RDA) exists, the AI can be used as a guide for planning nutrient intakes of individuals or as a target for the mean or median intake when planning for groups. The IOM has issued two separate reports describing in more detail how the DRIs can be applied to dietary assessment and planning (IOM, 2000b, 2003). Boxes 3-1 and 3-2 summarize how these applications differ between individuals and groups. In the United States this shift in focus from obtaining adequate intakes to minimizing excessive intakes began in 1977 when a United States Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs issued a set of recommendations known as the Dietary Goals for the United States (United States Senate, 1977). These goals provided quantitative recommendations on the amounts of complex carbohydrates, sugar, fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium that should be consumed. The Dietary Goals were controversial, in part because the diet plans developed to meet the goals were so different from the food patterns of typical Americans. Subsequently, a new publication, Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, was jointly issued in 1980 by the USDA and the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]). This publication has been revised six times since 1980. The 1995 revision was the first one to be mandated by the government as a result of the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act (NNMRRA), which requires the Secretaries of Agriculture and Health and Human Services to review and jointly issue the Guidelines every 5 years (NNMRRA, 1990). The purpose of the Dietary Guidelines is to translate information about individual nutrients and food components into an interrelated set of recommendations to help the public choose a healthy diet. The process used to create the Dietary Guidelines has evolved to include three stages: (1) an evidence-based review of the scientific literature; (2) the development of a policy document for professionals such as policy makers, nutrition educators, nutritionists, and health care providers; and (3) the development of messages and materials that communicate the Guidelines to the public. The seventh edition of the Guidelines—Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010—provides recommendations that encompass two overarching concepts (USDA/USDHHS, 2010):

Guidelines for Food and Nutrient Intake

Dietary Reference Intakes

Definitions

Criteria for Setting Dietary Recommendations

How DRIS are Used

Dietary Advice: Goals and Guidelines

Development of Dietary Guidelines

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine