Gross Description and Processing of Specimens

General Aspects of Gross Decription and Cutting in of Specimens

Endometrial Biopsies and Curettings

Uterus Removed for Benign or Functional Disease

Endometrial Sampling for Products of Conception

Introduction

The surgical pathologist reports the histopathologic diagnosis and specific information relating to prognosis and treatment. Therefore, one must have sufficient familiarity with the management of gynecologic and obstetric disorders to assure that the pathology report communicates the clinically relevant information. This chapter provides an approach to the processing of gynecologic and obstetric tissue specimens. The techniques of gross examination and the method of reporting the pathologic findings are guided by the clinical principles on which patient management is based. Several textbooks are now devoted entirely to this topic.1–3

The main purpose of a biopsy is to provide a histologic diagnosis that will guide management. Since biopsy specimens tend to be small and without specific gross features, the major pathology resides in the histology. The gross description is important mainly to ensure that what is received in the pathology laboratory and submitted for microscopic examination matches the slides returned from the histology laboratory for the pathologist to examine. Disparity between the findings on a slide and those expected based on the gross description is often the only clue that a slide or block may have been mislabeled. A good gross description therefore should be precise and brief. Examples of good descriptions are ‘3 ovoid fragments 2 to 4 mm in diameter,’ ‘multiple shreds of tissue 5 cm in aggregate,’ or the exact size given in three dimensions. For some specimens, it is also useful to note whether it is largely blood, mucin, or tissue.

Section Codes and the Report

Location of Section Codes in the Report

Most pathologists prefer a section code summary at the end of the gross text while some prefer entering block codes within the gross text. In either case, the report must be clear, both to the pathologist and to any person who at a later time will need to utilize the report. Block summaries, if used, may duplicate substantial parts of the gross, but cannot be used in its place. Including the block submission within the body of the gross description may be easier and more efficient for the person cutting in the specimen: ‘The borders in one region are sharp and distinct from the surrounding myometrium (Block B10) while elsewhere it blends into the adjacent myometrium (Block B11).’ However, having a section key at the end of the dictation may make histologic examination easier and more efficient. If the block codes are listed sequentially at the end of the report, the specific site and feature identified require presentation in sufficient detail so that the reader can easily link the gross description with the slide. Using the example above, it would be inappropriate for the coding block at the end to state that B10 and B11 are myometrium as it is unclear which section has the sharp borders and which has blurred borders. A section code at the end might better read, ‘B10 Myometrium, sharply circumscribed medial border, B11 Myometrium, blurred indistinct borders.’

General Aspects of Gross Decription and Cutting in of Specimens

Gross Description

The gross description, especially of small specimens, should conclude by stating how much of the tissue has been processed for microscopic examination. This is especially important in the case of endometrial curettings removed for a suspected intrauterine pregnancy where neither chorionic villi nor other tissues of fetal origin are found and all of the tissue has been submitted. Specify the number of each type of block sampled and from where each was obtained. An example of a useful gross description is ‘The endometrium, which is 2 mm thick, discloses no obvious tumor. The entire endometrium including the superficial myometrium is blocked and submitted in toto.’

Synoptic Checklists

As the complexity of information contained in reports increases and tumor cases are accessioned into trials with specific entry criteria, checklists are being used with increasing frequency to record and evaluate the details of operative and pathologic findings consistently. A full listing of College of American Pathologists specimen processing protocols, including synoptic checklists, is available online at www.cap.org.

Vulva

Excisional Biopsies

Biopsies of the vulva should be handled like skin biopsies. Assess the deep and lateral resection margins. If the surgeon has placed a suture for orientation, inking (often in several colors) facilitates recognition on microscopic examination.4

Wide Local Excision

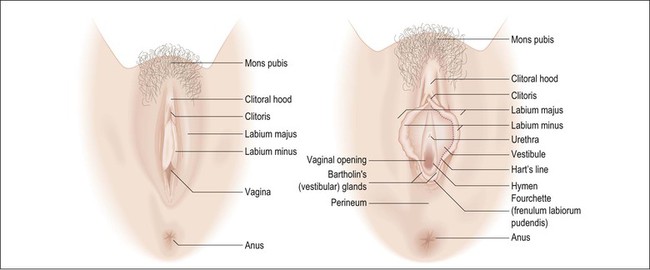

In general, wide local excisions are performed for noninvasive neoplasms such as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm (VIN) 3 or Paget disease of the vulva, as well as superficially invasive (less than 1 mm) stage 1 carcinomas. Lymph node dissections are added for stage 1B carcinomas (greater than 1 mm invasive). Orientation is critical in these specimens and, if not clearly indicated, consultation with the surgeon may be required. Operative specimens often include labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineal body, and perianal tissue (Figure 35.1). Describe and measure the lesions, distances to resection margins, and the anatomic structures involved. Examine the coloration and surface texture carefully as intraepithelial lesions are subtle, typically red-brown to white and roughened.

As intraepithelial lesions are often multifocal and difficult to discern macroscopically, all surgical peripheral and deep resection margins should be evaluated microscopically. Sections parallel to margins (‘tangential’) may be taken to evaluate the excision lines; however, one difficulty commonly encountered in parallel sections for evaluation of margins is to determine if tumor found in the slide truly involves the margin or was from the inner face, and therefore not a true representation of the margin.

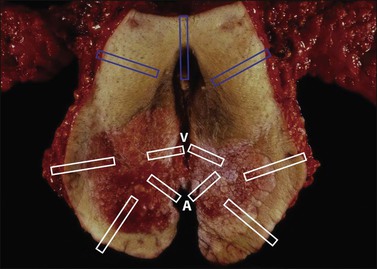

For discrete tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, multiple full thickness sections perpendicular to the skin surface and radiating outward from the lesion are advantageous as the central lesion, margins, and intervening areas can be included in one slide and tumor close to the margin is easy to evaluate (Figure 35.2). Facilitate sectioning by pinning the specimen on a corkboard or a block of paraffin and fix for several hours or overnight. Diagrams or photographs are often useful.

Simple (or Total) Vulvectomy

This includes the entire vulva and subcutaneous fat (dissection to deep fascia). It is typically performed for noninvasive neoplasms that widely involve the vulva. Pin, fix, and section the specimen at 0.5 cm intervals to evaluate for invasive carcinoma. Typically, the extent of Paget disease exceeds that visible macroscopically as occult foci are often present within normal-appearing skin. The resection margins must be thoroughly evaluated.2,5

Radical Vulvectomy

Radical vulvectomy consists of vulva excised to the deep fascia of the thigh, the periosteum of the pubis, and the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm. It is most commonly performed together with at least an inguinal lymph node dissection, which may be included en bloc with the vulvectomy. Total radical vulvectomies have largely been replaced in favor of more limited excisions, but sufficient to completely excise the primary tumor with a minimum 2 cm margin. Radical total vulvectomies are now performed primarily for large and/or aggressive tumors. The gross description should include the size, location, depth of invasion, and all resection margins, including perianal and vaginal margins. Sections should include the tumor, showing the maximum depth of invasion, labia majora and minora, clitoris, distal urethra, resection margins including the vaginal margin, and all lymph nodes. Separate lymph nodes into superficial and deep groups, and submit all lymph nodes entirely for histologic examination (unless grossly positive; in that case a representative section is sufficient). Invasive vulvar neoplasms are typically solitary in contrast to intraepithelial lesions, which are often multifocal. Consequently, evaluation of resection margins can be largely limited to the margins closest to the tumor. The report should include microscopic diagnosis, tumor grade, dimensions, location and maximum depth of invasion, presence of lymphatic invasion, number and location of involved lymph nodes, and distance to resection margins. Diagrams and/or photographs may be useful aids.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree