Learning Objectives

- Understand how health communications research and campaigns impact the wellness of individuals and communities globally

- Describe the role of news media, social media, trusted community members, participatory communication, and “edutainment” in health promotion and education

- Define common barriers to health communications research and delivery, particularly in developing countries and with underserved minority populations worldwide

- Explain the principles of social marketing to deliver health information and services and to change behaviors

- Show how mobile phones and other information communication technologies can accelerate access to knowledge, spur innovation, and improve health

Introduction

One significant driver of improvements in public health globally over the past 40 years has been the increased understanding and employment of health communication research, campaigns, and technologies, as well as social marketing strategies.

Health communications research provides a picture of the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals and communities. Health communications and social marketing campaigns use multiple channels to raise awareness and provide culturally appropriate messages about disease, environmental conditions, nutrition, safety, literacy, and a host of other issues. The communicators must understand individual and community needs and wants, as well as the social and political pressures and competitive forces. They will then be able to inform the people of the community in a manner they trust. This process should help the community be more open to receiving the communication and can lead to motivating them to change behavior and, ultimately, to improving their health and productivity.

Interventions to advance global health have centered typically on clinical and research endeavors, but that has been changing over the past three decades. An important missing piece of the prevention-treatment puzzle was the strategic use of health communication and marketing tools that can empower communities with the knowledge, motivation, and incentive to improve their environment and wellness, and in return, their social and economic potential and sustainability.

Many examples of health communications and social marketing success in changing behaviors and improving health now exist. Effective global health practitioners, particularly those working in developing countries, understand the importance of using communications and marketing at all stages of behavior change. To impact entrenched beliefs and practices, as well as open up access to new knowledge, health communications and marketing must continue to be an essential piece of community-driven global health strategies.

- Health communications research and program development

- Applying a social marketing process to improve and sustain healthier behaviors

- Partnering with media to promote and inform

- Tapping into the latest communication technologies to empower individuals and communities with new health knowledge and increased ways to stay connected, share their stories, and sustain lasting positive behavior changes

Health Communications and Promotion

Eliminating or diminishing the burden brought on by the overwhelming diseases of our day calls for aggressive clinical prevention, treatment, and research, but also connecting meaningfully with individuals and communities to promote healthy behavior change. Human behavior plays a significant role in the leading causes of disease, disability, and death. By itself or with other strategies, health communications can inform and influence individuals and groups to quit smoking, use contraceptives, sleep under insecticide-treated bednets, fortify with iron the foods they produce, get an annual mammogram, make their own oral rehydration therapies, filter their water, stay compliant with medications, properly fund immunization programs, exercise regularly, refute myths, or begin to change long-held destructive cultural practices.

Health communications has been defined many ways, but essentially it is the use of communications planning, research, strategy, tactics, and evaluation to increase knowledge and motivate action that improves health. Combined with adequate health services, technological advances, necessary infrastructure, and responsive policies, it can bring about sustained changes that transform individual, community, and global health status for the better.

Early use of health communications relied on one-way messages such as “Don’t pollute!” or “Don’t do drugs” that spoke only to the action the researcher or program leader wanted to bring about. By not taking into account what motivated the related action, what kind of need it fulfilled, what social or economic pressures the individual faced, the one-message campaigns had limited impact. But increasingly, health communication professionals have learned that to achieve the desired outcome of improved health, solid research and evaluation must be employed. Program development and delivery must reflect the needs, wants, and cultural values of the community (rather than a “top-down,” Western mindset approach). Program developers must tap creatively into channels of communication that are easily accessed—or can be driven—by the target audience. Because communication and marketing efforts aim to motivate an individual or group to take some type of action based on their needs and wants, it is useful to understand what may influence an individual within their “social and health ecosystem.”

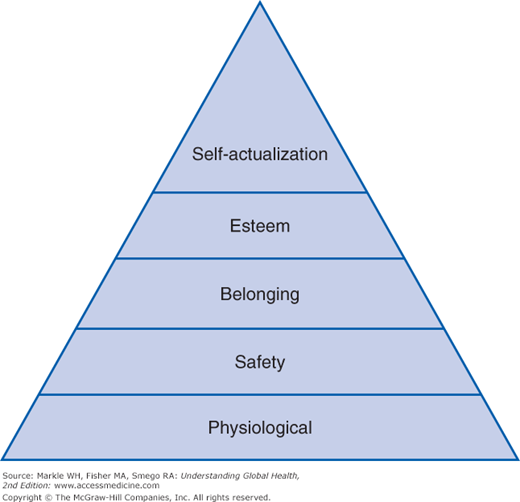

A well-known model involving motivation is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs shown in Figure 18-1.1 Maslow constructed this theory based on individual behavior and needs, described in the form of a pyramid. As the basic physiologic needs of food, water, shelter, and security are addressed, individuals seek to attain successively “higher needs” such as the social elements of friendship, family, belonging, and love, and then they may be motivated by self-esteem, ego, achievement, and respect of others. At the top of the pyramid is the need for self-actualization and fulfillment. Maslow championed this as reaching one’s full potential, with motivation not centered on the self, but rather understanding and helping to solve problems of the wider community.

Applied to global health, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be particularly useful in understanding where the greatest needs are of the individual and community, and how to best position messages, materials, and programs to that level or a higher aspired-to level so they have the most meaning and relevance. If a core set of youth aspire to become leaders in their community, communications and marketing can be directed at their “stepping up” and being recognized for taking action that benefits the entire community. They could help develop the message, advertising, and campaign and be featured in it, which could add credibility. Examples include their choosing to be tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or the effective “Truth” stop smoking campaign, designed and developed by US teenagers who describe the reality of why they choose not to smoke.

The values realized at self-actualization (acceptance of other views and traditions, lack of prejudice, using creativity and spontaneity, pursuing solutions to broader problems) parallel the qualities needed by global health communications professionals to effectively change behavior and improve health conditions. Maslow also exhibited a worldview when, in explaining self-actualization, he defined it as when one transcends cultural conditioning and becomes a world citizen.

Many levels of influence affect a group or individual’s behavior, and health communications professionals must take these into account when designing effective strategies. These include individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy factors.2

Health communications, sometimes referred to as “behavior change communications,” can affect individual knowledge, attitudes, practices, skills, and dedication related to the desired change. Information and programs aimed at informal interpersonal relationships present with family, coworkers, barbers, bus drivers, health professionals, and so on, can be effective because they come from known respected sources. Targeted health messages and calls to action to formal institutional groups of like-minded individuals can influence behavior. Organizations can reinforce health information and support programming for their members that promote screenings and expectations of healthier living. Knowing the norms and standards, and gaining the support of trusted community leaders, elders, and key peer groups can go a long way toward advancing and sustaining a behavioral change communications process.

Finally, efforts to impact public policy and societal views and laws can be realized through a comprehensive health communications approach that educates, personalizes, and motivates the public, industry, and government to change the norm and take action for the greater good. Examples include work related to transportation and public safety: increasing the wearing of seatbelts in the United States and reducing the number of passengers allowed by law riding in Kenyan public mini-buses or matatus.

Effective health communications should start with the use of single or multiple theories and frameworks to build appropriate goals, structure, implementation, impact evaluation, and sustainability with various audiences. Each individual, community, or country presents special challenges and opportunities, and the global health communications professional may combine various theories to understand and influence behavior change related to the problem(s) faced.

Theories and models do not take the place of quality planning and targeted community-driven research. However, they can serve as a foundation during the formative stage of planning health communication initiatives and provide insight as to what may motivate and resonate with the audience when the program is rolled out. They can also highlight some of the outcomes that should be considered when evaluating programs or campaigns.

For a summary of some of the most commonly used health communications frameworks, theories and models, see Table 18-1.

Level | Theory/Model/Framework | Description |

|---|---|---|

Individual | Stages of change model | Focuses on individuals’ readiness to change or attempt to adopt healthy behaviors. Behavior change is a process not an event, and individuals are at different levels of motivation to change. |

Health belief model | Centers around: perception of risk of acquiring a health condition; the severity of the consequences; the perceived benefits of adopting the behavior; the barriers and cues to action that may hinder or spur the change. Also factoring into individuals’ decisions: are they capable of making the change and sustaining it? Demographic issues and knowledge level play a role. | |

Behavioral intentions theory | Suggests that the likelihood of intended audiences’ adopting a behavior can be predicted by researching their attitudes toward the behavior’s benefits, in addition to how their peers will view their behavior. | |

Interpersonal | Social learning theory | Explains behavior as a three-way “triadic reciprocal” relationship in which environmental issues, personal factors, and behavior interact and shape each other. |

Community | Community mobilization theory | With roots in social networks, it emphasizes active participation and community development where the community helps identify, plan, implement, and solve problems with coordination from outside practitioners. Capacity building and addressing social injustices for the oppressed are hallmarks. |

Organizational change theory | Involves processes and strategies for increasing the likelihood of a formal organization adopting healthy policies and programs. | |

Diffusions of innovation theory | Addresses how new ideas, products, and social practices spread within a society or from one society to another. Examines the innovation, the channels, and the social networks involved. | |

Individual, interpersonal, and community | Social marketing framework | Centers on applying proven marketing technologies and research for developing, executing, and evaluating programs that influence voluntary behavior change to improve individual welfare and the society they live in. Focuses on research, the customer, and changing behaviors, rather than attitudes/knowledge. |

Improving the health of individuals and communities through communications starts with understanding the needs, strengths, and perceptions of the population, and exploring whether the program or desired behavior changes can be successfully adopted. Will the individual, community, organization, or policymaker agree that the benefits to making the change outweigh the costs? What are the barriers to getting a clear picture of the capabilities of those you want to inform and influence? Have programs worked in the past? If not, why? What tools or channels are available to communicate the information in a convincing and credible way? Are the resources available to impact awareness, provide incentives, and motivate sustainable change over time? Who are the trusted individuals that can help carry the messages and bring about the change in behavior?

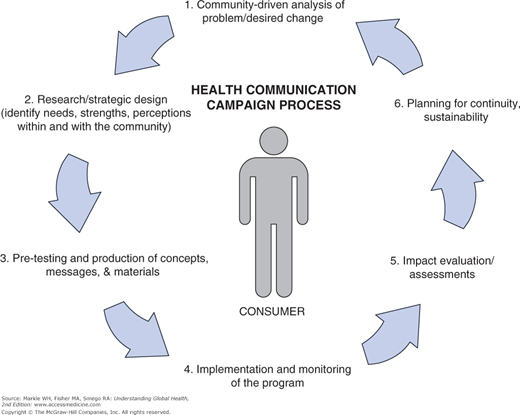

As seen in Figure 18-2, several basic stages are involved in developing a successful health communications program. The process is fluid, with steps overlapping, but these represent the basic ingredients:

- Starting with a perceived problem and the desired change to bring about

- Using existing or conducting new research, and setting strategies

- Working with the community closely in the development and testing of messages and materials

- Implementing the program

- Assessing its impact on the goals and success

- Planning with the community for sustaining the program and the healthier behavior changes

Successful strategic behavior change campaigns are also benefit oriented, can be expanded to scale, and are cost effective.

Let us take a closer look at what needs to be considered and done at these different stages for behavior change communications to work in the global health setting.

Analyzing Problems, Creating Interventions, Improving Lives: A Hopi Story

You could take several approaches to discerning the initial core problem you want to address through health communications and marketing, implementing and evaluating the program, and sustaining the behavior change. The approach you choose will depend on your health field, experience, affiliated organization’s focus, and familiarity with the region/community you are working in.

You are part of a clinical team that wants to understand why health providers in a rural Indian Health Service clinic keep seeing female patients come in with the same condition of malnourishment and iron deficiency, even though they were provided written instructions on how to prevent it. The 3-minute clinic exchange between the Ivy League–trained doctor and the Hopi mother does not provide either party much opportunity for communication or discussion about underlying issues and barriers to her maintaining good nutritional health.

So you, as a health communications researcher, know research must be done within the community to get at the core problem. You find out who the respected women leaders of the village are and arrange to conduct several interviews with them in their homes, a place where they feel comfortable and more confident. After multiple group discussions, a common theme surfaces related to the issue: it is culturally inappropriate for a Hopi mother to focus on her own nutritional needs until her children and husband have plenty to eat. Because nutritious food is not abundant, you find she often goes without, skipping meals or not having access to fruits and vegetables after she takes care of the others.

Armed with that knowledge, you start to design a communications campaign, with the help of the women, that involves the entire family and community, and which supports the message that the mother’s health matters much to the health of the family and to the wider community. The strategy will use multiple channels—from social media to radio to entertainment—to inform and influence, and you will involve traditional healers giving their blessing that an iron supplement will be safe to add to Hopi meals.

You identify women who are leaders to step forth to educate other women and families, and local lay health promoters agree to work with the Western physicians to increase their cultural awareness. A local youth group volunteers to incorporate the “good nutrition for mother” themes into a new play they will perform at the community’s Hopi Corn Festival.

As part of your strategy, you enlist the aid of radio stations on the reservation to air future public service announcements (PSAs) from women to women about the importance of eating well and staying healthy. Similar content is planned for use on Twitter, YouTube, and a storytelling Website where community members tell their stories in their own voices.

Since you received your public health training at a university in Ohio, you ask the university’s creative services team to help write and produce the campaign materials. They produce high-quality publications with content you provide, a script for the PSAs, and a short video for YouTube. Slick posters, ads, video, new Twitter account, and brochures in hand, you are understandably excited as you go to the Hopi community center to share the prototypes of the campaign materials. Your presentation is met with uncharacteristic silence and expressions of chagrin.

After some prodding, you hear reasons why these materials will not work. Some Hopis consider the centipede symbol on the brochure cover taboo. The sepia tone photo of the traditional kiva structure inside depicts a ceremonial home where women were only allowed in to serve food and clean. There are only photos of individuals by themselves, which certainly does not express the positive Hopi concept of “Naya,” which means people working together for a common good. The music provided for the PSA and video is Tibetan, not traditional or modern Hopi. Finally, the glossy paper stock is not made from recycled materials—not appropriate given the sacred value Hopis place on the environment and their emphasis on recycling and reusing.

This is an example of why pretesting of materials, health messages, and calls to action with the community for the community are so vital. Sometimes tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent on a campaign by well-intentioned but culturally out-of-touch communications professionals who bypass pretesting and then do not understand why the communications campaign failed so miserably to change behavior and improve health.

You dig deeper and find right in the Hopi community creative writers, illustrators, designers, student actors, and a printer who understand the Hopi traditions, and redo the materials so they reflect the Hopi experience and will hopefully better resonate with the audience. The health messages must be developed in the Hopi context.

You meet a fledgling young Hopi filmmaker who agrees to produce a short video aimed at young husbands, an important segment of the market because your research showed the need to include men if the traditional views about food security and mothers were to change. Hearing about the excitement generated by this project, a well-known Hopi actor volunteers to do the vocals for the PSAs and agrees to raise funding for sustaining the effort through the online entrepreneurial Website, http://kickstarter.com.

Having taken the time to learn about the rich tradition of storytelling among the Hopi, you work to create a Hopi section on http://cowbird.com, a Website where individuals can add their photos, videos, and words to create a larger mosaic reflecting a community’s story.

Knowing the importance of evaluation, you included in your earlier research a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey of community members’ knowledge of nutrition and family health, attitudes about gender roles in the home, and their current behaviors related to the problem. This sets a benchmark you can measure against in 6 months to see if the campaign is working.

You kickoff the “Iron Mothers” campaign by making it one of the featured elements of the Hopi Corn Festival, which includes family health screenings and nutrition counseling from Native American health promoters. The nonnative clinic physicians assist with the screenings and passing out multivitamins with iron. The local creators of the campaign materials are honored for their contributions to strengthening the Hopi community.

The PSAs air every day, a nutrition health column is written weekly for the local newspaper and placed on the new Website created for the campaign, and the culturally relevant publications connecting the health of the mother to the well-being of the Hopi community are distributed to homes and businesses. A comic book for kids written in both Hopi and English tells the story of a child who becomes a superhero by keeping his mother healthy and strong. Kids dressed as superheroes help lead a march through a retail section of town, raising social pressure for more affordable access to vitamins and nutrients. The story continues online via the Native American, youth-focused Website, “http://wernative.org,” and user-generated content from the community grows.

To sustain the program’s momentum, monthly community events weave in the health message and materials. The high school football team premiers the 5-minute video at halftime on the scoreboard. The theater group debuts its nutrition-inspired production, “Food Fight,” and the strong, energetic mother character becomes a favorite of the packed house. Students at the local community college create a free mobile application for smartphones that helps families track nutrition and diet, and find healthy, affordable foods close to home. Pharmacists and discount stores in the area announce an unprecedented cooperative buying strategy to purchase multivitamins and iron supplements in bulk and sell them at a heavy discount to women in the “Iron Mothers” program. Mothers and their spouses and children begin coming to the clinic together each month for screenings and checkups with the physician and a newly hired Hopi nutritionist. Finally, after much advocacy from many groups and individuals, the tribal government passes legislation to use a percentage of the grocery tax to consistently fund low-cost vitamin supplements for families in need.

After 6 months, the clinical results look good: 80% of the women enrolled in the program now show normal iron levels compared with only 35% before, and the levels for other women outside the program coming to the clinic have risen as well. You conduct another KAP survey with the families, showing more support from men for helping to keep their wives, sisters, and mothers healthy, and a marked increase in children’s understanding of why their mothers need to have fruits, vegetables, and vitamins too. Women overall are missing fewer days of work, a positive result that benefits both the family and the community.

By all accounts, the “Iron Mothers” health communications and marketing campaign was making a real difference—with individual and community health, but also capacity building. Thanks to the social, community, and business networks built to support it, the tapping of Hopi community talent to help produce it, and the pride of knowing the mothers, families, and the Hopi community were growing stronger because of it, the possibility of sustaining the effort and making it part of everyday life appears high.

This hypothetical campaign worked because it followed the framework for researching, designing, testing, implementing, and evaluating a health communications effort. But it also engaged the community to lend its knowledge, talent, and passion in developing creative ways to keep attention on this problem and to bring about the desired behavior change and health improvement. The program, grounded in the values of the Hopi tribe, employed research to study the problem and measure success, as well as various communication technologies to deliver the messages. Finally, it always stayed focused on the consumer (the mother) and the benefits to her, the family, and community.

Cross-Cultural Health and Communications

Health providers, educators, and media wanting to improve their communications and health care outcomes with underserved minority communities such as the Hopi must understand the value and belief systems they bring with them, and link the program’s benefits to the deeper values held. An example is the Latino population, which is growing rapidly in the United States, whose core values and beliefs often include:

- Familismo (significance of the family to the individual)

- Collectivismo (importance of friends, extended family)

- Simpatia (need for positive, relaxed relationships)

- Personalismo (preference for friendly relations with members of their same ethnic group)

- Fatalismo (little belief or experience with prevention— there is little an individual can do to change his or her destiny)

- Respeto (deferential treatment to those based on age and position)3

Of all of these beliefs, fatalismo is perhaps the one that keeps Latinos from taking prevention measures for their health or being motivated to manage a chronic health condition like diabetes. Some feel they cannot do anything about a condition like diabetes, most think insulin is harmful, and many avoid health screenings because of the belief that if you do not know you have the disease, it must not be real.4

Many Latinos believe that “stress, fear, and anger” bring on diabetes. Although “stress, fear, and anger” are not direct causes of diabetes, it is not surprising that Latinos would view them as so, given their cultural values and the need to keep life in simpatia or harmony to maintain good health. Regarding what motivates them to exercise more may point to the need for health communications researchers, community health providers, and policymakers to consider the Latino belief system centered around collectivismo, or the importance of family and friends working together collectively toward a shared goal or interest.

This was borne out in a Columbus, Ohio, survey of new Latino immigrants’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice about health and media use. In response to a question about what would help them exercise more, many responded “if friends or family were involved,” and “if there were free programs at a park or organization near where the family lives.”5

Health promotion and communications campaigns can dispel misconceptions about the causes of disease and build on strengths in communities, such as collectivismo and simpatia with Latinos, in designing and implementing health marketing that motivates and changes behavior in a positive way.

Belief systems play an important role in how diseases are perceived in other cultures as well. Some Native Americans believe that if they are ill, they brought it on themselves. African Americans are often tested for conditions such as HIV or diabetes later than other groups, sometimes referred to as “last to test.” This view may be akin to the Latino fatalismo belief that knowing one has a condition may not matter either way, so why confirm it.

With this cultural lens in mind, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Testing Makes Us Stronger” national campaign targets men who have sex with men (MSMs) in the African American community. The message? Knowing one’s HIV status is important and empowering information. The campaign—developed by an expert panel of black gay and bisexual community leaders working with the CDC—features bold, strong messages and images in digital, print, Web, outdoor, and transit ads.

The “Testing Makes Us Stronger” campaign shows men taking responsibility for their bodies and their HIV status, thereby making themselves, their partners, and their community stronger. The campaign runs in select cities experiencing high levels of HIV infection in African American gay and bisexual men (HIV rates can be three times higher among black MSMs in the United States than white MSMs). More than 400 black men in five US cities helped refine the messages used in the campaign, a strong testament to the need for health communications campaigns to be driven by the core community where the hoped-for changes would take place.6

The stigma surrounding conditions in certain cultures, communities, and societies can be a particularly intractable barrier to overcome—for both the individual and for health communications practitioners. Those living with mental illnesses, for example, face societal prejudices borne out of a lack of information or a prevailing stereotype. The result is that a soldier returning home from conflict may not seek needed treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder, or a mother experiencing a deep depression is not comfortable discussing it with her family or receiving treatment from her doctor.

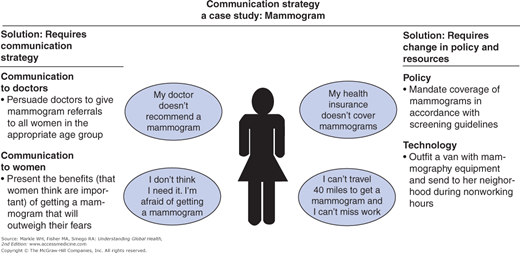

Successful health outcomes may require a strategy that delivers multiple communications to the audiences that, when combined, influence whether the change can be made. For example, to increase the number of women receiving mammograms, a successful campaign will need to communicate different messages to doctors and women, as well as help push for change in health policy to provide needed resources and technology (see Figure 18-3).

Figure 18-3.

Communication strategy: increasing mammogram use. From Making Health Communication Programs Work7. (Reproduced with permission.)

Health communications professionals possess many outlets and strategies for making sure key messages are relevant, accepted, and acted on. Some of the methods for designing effective campaigns include the following:7

- Media literacy: Instructs audiences on how to understand media messages to identify the sponsor’s motives, and how to compose messages targeted effectively to the intended audience’s point of view

- Traditional and new media advocacy: Seeks to change the social and political environment in which decisions are made by influencing print, digital, and social media’s selection of stories and by shaping the debate about those subjects

- Public relations: Advances certain messages about a health issue or behavior to the media or other influencers to raise knowledge and increase attention around the topic

- Advertising: Places paid or public service messages in the media or public spaces to increase visibility and support for a product, service, or behavior

- Education entertainment: Often called “edutainment,” it seeks to integrate health-promoting messages and storylines into popular culture entertainment and news programs; also seeks entertainment industry support for a health issue to multiply the effect

- Individual and group instruction: Influences, guides, and provides skills and incentives to support positive behaviors

- Partnership development/advocacy: Deepens support for a program or issue by attracting the influence, credibility, and resources of profit, nonprofit, or governmental policymakers

According to McGuire’s “Communications for Persuasion,” to communicate the message successfully, these five communication elements all must work:

- Credibility of the message source

- Message design

- Delivery channel

- Intended audience

- Intended behavior8

In all areas, but particularly in developing countries, several challenges to effective communication programs may exist. These include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree