Maryann Papanier Wells and Allison Lindsey Flanagan

Geriatric Surgery

The elderly contingent is growing in leaps and bounds in today’s population, and consequently perioperative nurses must be proficient in meeting the needs of geriatric patients. As a geriatric patient, a different set of variables becomes important to maintain one’s lifestyle. First and foremost, the older adult generation wants to live independently, care for themselves, and keep their quality of life intact.

Aging is a process that can be described in chronologic, physiologic, and functional terms. Human aging from a physiologic perspective has changed little in the past 300 years. In general, we age neither faster nor slower than we did in Colonial America. Chronologic age, the number of years a person has lived, is an easily identifiable measurement. Average or median life span, or life expectancy, is the age at which 50% of a given population survives. Maximum life span potential (MLSP) is the age of the longest-lived member or members of the population or species. Although the number of people living beyond their 90s has increased more recently, the MLSP, estimated at 125 years for women and somewhat less for men, has not changed significantly in recorded history. Chronologic age or MLSP may not be the most meaningful measurement of age, however. Nevertheless, many people who have lived a long time remain physiologically and functionally young, whereas others are chronologically young but physiologically and functionally old (Wold, 2012).

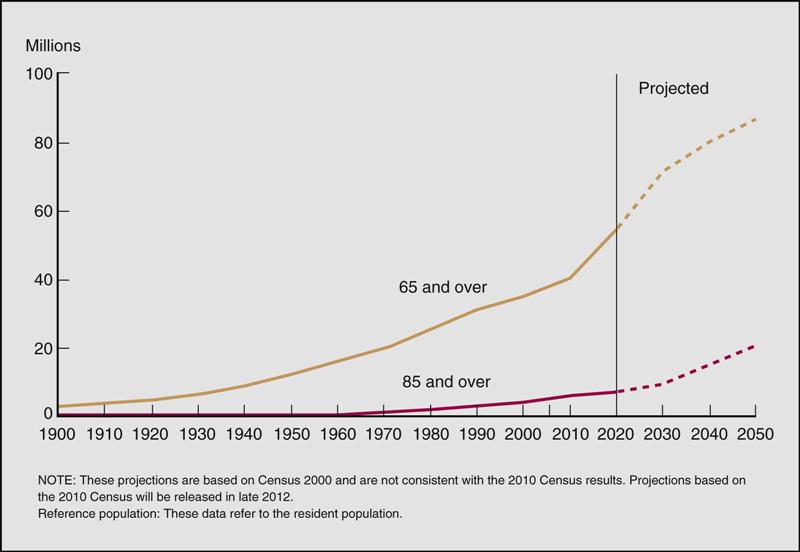

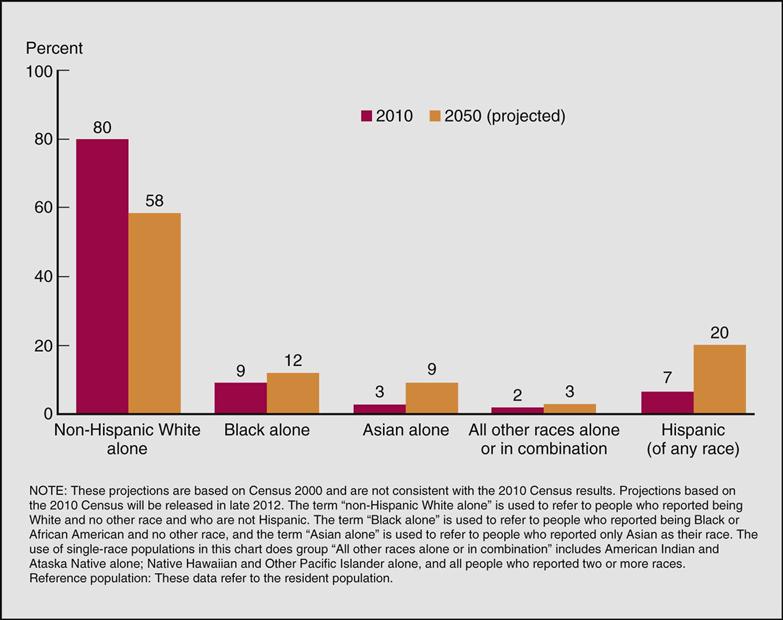

Many aspects of our society will be affected by the growth of the population that is 65 years old or older. Policymakers, families, businesses, and healthcare providers will be challenged to meet the needs of this growing age group. With the aging of the baby-boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), the gerontology boom will occur somewhere between 2010 and 2030, producing the most rapid increase in the older population. Individuals older than 85 years now make up 4% of the entire U.S. population and represent the fastest growing segment of the older population. Economics will play a factor because individuals born before 1937 will still qualify for full Social Security benefits at age 65 with incremental increases regarding benefit age for everyone born after that time. Those born in 1960 or after will have to wait until age 67 to qualify for full benefits, with reduced benefits calculated for individuals who apply for benefits after age 62 but before the specified retirement age (Wold, 2012). Nearly 36 million people 65 years and older lived in the United States in 2003, accounting for more than 12% of the total population, and they can be divided into four subgroups (Box 27-1). The population considered oldest-old (age 85 years and older) increased from just more than 100,000 in 1900 to 4.2 million in 2000. In 2011 baby-boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) started turning 65 years old; this segment of the population will increase at such a rate that the 2030 population is projected to be twice as large as it was in 2000. The 65-year and older population will increase from 35 million to 72 million, representing nearly 20% of the total U.S. population. In 2012 there were 40 million people age 65 and older, accounting for 13% of the total population (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics [FIFARS], 2012). The growth rate for this age-group is expected to stabilize at around 20% of the population after 2030, when the last of the boomers join the older population ranks. After 2030 the baby-boomers will move into the oldest-old population (age 85 and older), which will grow accordingly (FIFARS, 2012; Figure 27-1 provides population data). The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the population age 85 and older could grow from 5.7 million in 2008 to nearly 19 million by 2050 (Wold, 2012). The proportion of the older population (65 and older) varies by state. This proportion is partly affected by the state fertility and mortality levels and partly by the number of older and younger people who migrate to and from the state. In 2010 Florida had the highest proportion of people ages 65 years and older at 17%. Maine, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia also had high proportions: more than 15%. The proportion of the population 65 years and older varies even more by county. In 2010 43%% of Sumter County, Florida, was 65 years and older, the highest proportion in the United States. In several Florida counties the proportion was more than 30%. At the other end of the spectrum was Aleutians West Census Area, Alaska, with only 3.5% of its population 65 years and older (FIFARS, 2012). As in most countries of the world, older women outnumber older men in the United States, and the proportion that is female increases with age. In 2010 women accounted for 57% of the older population and for 67% of the population 85 years and older. The United States is fairly young by comparison with other countries, with just more than 13% of its population age 65 years and older. In most European countries the older population comprised more than 15% of the population, and it included nearly 20% of the population in both Germany and Italy in 2010 (FIFARS, 2012). Mirroring the total U.S. population, the elder population is more racially diverse than ever. By 2050 programs and services for older people will require greater flexibility to meet the needs of a more diverse population. In 2010 non-Hispanic whites accounted for 80% of the U.S. older population; African Americans accounted for 9%; Asians 3%; and Hispanics (of any race), 7%. Projections are that by 2050 the composition of the older population will change to 58% non-Hispanic white, 20% Hispanic, 12% African American, and 9% Asian. The older Hispanic population is projected to grow the fastest, from just under 3 million in 2010 to 17.5 million in 2050, and to be larger than the older African American population. In 2010 over 1 million older Asians lived in the United States; by 2050 this population is projected to be 7.5 million (FIFARS, 2012). Figure 27-2 illustrates resident population by racial and ethnic composition.

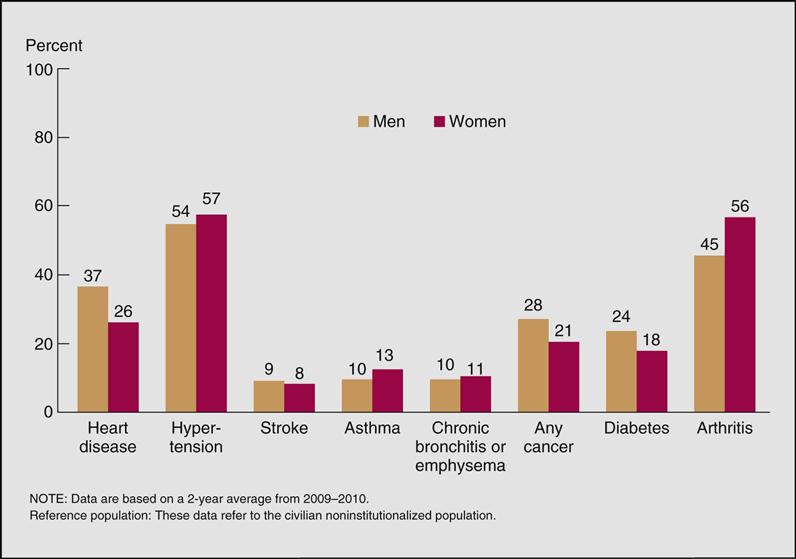

Those older than 85 are the fastest-growing age group among the U.S. population. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2010, 3.1% of the U.S. population was at least 100 years old, compared with 0.1% in 1901. The total number is expected to increase by 400% by 2030. Translating these demographics into healthcare trends produces even more startling implications for perioperative patient care. As a result of the “graying of America,” healthcare will never be the same. Most older adults have at least one chronic condition, and many have multiple conditions. Chronic diseases that are rarely cured, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, are among the most common and costly health conditions. These long-term health conditions negatively affect quality of life, contributing to declines in functioning and the inability to remain in the community. Although chronic conditions can be prevented or modified with behavioral interventions, six of the seven leading causes of death among older Americans are chronic diseases (FIFARS, 2012) (Figure 27-3 lists the percentages of chronic diseases by gender). Between 1992 and 1999, the hospitalization rate in the older population increased from 306 hospital stays per 1000 Medicare enrollees to 365 per 1000. In 2009 the rate decreased to 320 per 1000 enrollees, and the average length of stay decreased from 8.4 days in 1992 to 5.4 days in 2009. The number of Medicare enrollees staying in skilled nursing facilities increased from 28 per 1000 in 1992 to 80 per 1000 in 2009. The utilization rates for many services change based on changes in medical technology and physician practice patterns (FIFARS, 2012). The dramatic growth in elderly surgical patients punctuates the necessity for perioperative nurses to recognize the special needs of these patients. Understanding how normal aging changes and chronic disease affect the successful outcome of any surgical procedure is critical and is therefore the emphasis of this chapter.

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Preliminary Evaluation

Before an elderly patient actually arrives in surgery, the physician considers many factors to determine whether the benefits of surgery outweigh the potential risks. In the past, elders were not considered good candidates for surgery merely because of age. Uncertainty about the value of surgery in elders and about the operative risks prevailed. Because surgical morbidity and mortality increase with age and complexity of disease conditions, a thorough understanding of the physiology of aging is necessary when considering surgery on older patients (Evidence for Practice). Although improvements in technology, monitoring techniques, and anesthesia have made surgery safer for older adults, age remains a significant risk factor. Nevertheless, adequate assessments of the functional age and the physiologic reserve of the elderly surgical patient are of paramount importance (Wold, 2012).

According to Kim and Zenilman (2007), the occurrence of perioperative mortality in geriatric surgical patients is influenced by three factors—presence of coexisting disease, emergency surgery, and site of surgery:

Surgical decision-making regarding elders can be difficult. As the baby-boomers become seniors, they will be very different from healthcare consumers of the past. They will tolerate less and expect more. In clinical practice today, patients are increasingly involved in clinical decision making. Patients are willing to actively participate in shared decision making. Emphasis is on patient involvement in medical decision making as a result of the growing amount of information available through the Internet, patient education materials, advertisements, and public quality reporting databases (Slover et al, 2012). The age structure in the United States is changing because people are living longer. The aging baby-boomers are creating a greater demand for surgical services, and this presents challenges to the healthcare system. Surgeons will have to meet the increased demands while guaranteeing high-quality care (Zenilman et al, 2011). Elderly patients have an increased tendency for slower metabolism, multiple chronic diseases, and a decreased reserve capacity of their organs to respond to stress, as compared to younger patients (Dardik et al, 2012). What should be considered is the risk of not operating and the quality of life expected. Although the recommendation for surgery is within the purview of the physician, perioperative nurses should be aware of its implications. Surgical intervention and management should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms, overall functional and health status, and the predicted advantage of palliative intervention. Important factors that need to be evaluated are:

The following considerations should be included when deciding to proceed with surgery in elders (Dardik et al, 2012):

• Is there a clear indication for surgery, including a likelihood of disease progression?

• What practical limitations will be imposed on the patient with the progression of the disease?

• How much improvement can be expected after the surgical procedure?

• What is the expectation for quality of life with or without the surgery?

• How aware is the patient and the patient’s family about the problem and proposed solutions?

• Has an adequate preoperative assessment and preparation preceded an elective procedure?

There are many important considerations related to the extent of surgical treatment. Therefore, the decision for surgery relies heavily on the patient’s physical status at the time of surgery and on the extent of disease progression. When treating patients who are nearing the end of life, attention should shift from solely maximizing survival to maximizing the quality of life and dignity while minimizing suffering. Early identification of problems with aggressive, preventive surgical treatment is considered more appropriate than waiting for problems to develop.

Perioperative nurses have a unique opportunity to assess and screen for signs of emotional and physical abuse in elderly patients during their preoperative assessment and while assisting with surgical positioning. Box 27-2 lists signs that may indicate abuse. If such signs are present, the perioperative nurse should report the suspected abuse to the appropriate authority. Reporting laws and regulations vary by state and facility.

Assessment

In elderly people a preoperative medical assessment is conducted to determine present physiologic functioning. When compared with younger people, the geriatric population may be more vulnerable to certain adverse events that may significantly affect their outcomes (Zenilman et al, 2011). Predicting surgical risk in the elderly can be challenging. According to Zenilman and colleagues (2011), frailty describes the global phenotype of a patient with decreased physiologic reserve and ability to withstand stress. Frailty is becoming an increasingly recognized tool to measure a patient’s physiologic reserve. Frailty status is categorized in a standardized way as “frail,” “intermediately frail,” and “non-frail.” Frailty is determined using a five-domain assessment tool including shrinking, weakness, exhaustion, lower physical activity, and slowness. Shrinking is considered an unintentional weight loss of 10 pounds or more in the past year. Weakness is determined by assessing grip strength. Exhaustion and lower physical activity are assessed by giving the elderly patient a questionnaire. Slowness is assessed using a series of walking trials (Zenilman et al, 2011). Not all elderly people are frail and not all frail people have active disease, but measuring frailty provides surgeons with a tool to predict postoperative outcomes. Solely using chronologic age as a predictor of a patient’s response to surgery is not a reliable measurement. It gives little indication of the physiologic or biologic age and condition of a person. For example, a 75-year-old person can be in better physical and mental condition for surgery than a 65-year-old. Biologic age as a measurement criterion is much more reliable. Establishing biologic age, however, becomes the greatest challenge. One tool, the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), is a multidimensional evaluation that scrutinizes medications, functional ability, comorbid conditions, cognitive ability, mental function, nutritional status, and socioenvironmental factors. The CGA may be used both to identify at-risk individuals and to guide interventions. When evaluated as a screening tool in the geriatric community, it has been shown to detect new and unsuspected problems in 76% of elderly persons living at home. In geriatric medical studies the CGA has been found to be potentially beneficial in reducing the incidence of hospitalization, falls, delirium, and readmission. It is predictive of both morbidity and mortality in older patients (Kim and Zenilman, 2007).

Evaluation of functional status typically includes assessment of the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) (personal care tasks) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (everyday tasks). The scoring system that is employed for assessing comorbidity in surgical patients is the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification (see Chapter 5). Additional measures of comorbidity include the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for geriatrics and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Kim and Zenilman, 2007) and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) clinical management guidelines (2012). The AGS guidelines promote a patient-centered approach (Patient-Centered Care).

Impaired nutritional status is highly prevalent among the elderly; as many as 12% of men and 8% of women in the healthy geriatric population are considered undernourished. Higher rates of surgical complications and increased postoperative mortality have been observed in patients with poor nutritional status, as determined by a low body mass index, weight loss, a low preoperative serum albumin level, or a low Mini Nutritional Assessment score. Preoperative cognitive dysfunction has been associated with increased postoperative complications and worse survival in elderly surgical patients. Cognitive ability can be assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Kim and Zenilman, 2007).

Depression and the lack of social support are also linked to adverse outcomes in older surgical patients. A tool that is commonly used in screening for depression in the elderly is the Geriatric Depression Scale. Several tools are available for quantifying social support resources in elderly patients. One such tool is the Medical Outcome Study Social Support Survey, which yields a score on a scale of 0 to 100 and includes “emotional” and “tangible” subscales. Another commonly used measure of social support is the Seeman and Berkman Social Ties Score, which measures social ties in four different areas.

An interdisciplinary approach is necessary to consider the complex health needs of the elderly patient in an effort to provide quality care. Application of these findings identifies operative risk, minimizes postoperative complications, and establishes the presence and status of any concomitant disease process that could negatively affect the outcome of the surgery. The preoperative nursing assessment is conducted to plan patient care throughout the perioperative period. In particular, assessment data are used to establish presurgical baseline data so that health status changes, primarily during the intraoperative and postoperative periods, are more readily recognized. The nurse’s data collection includes the standard assessment information with considerations of coexisting conditions and a review of the patient’s medication list (Box 27-3). Polypharmacy is an issue for many elderly patients and is a concern because of the physiologic changes associated with aging that lead to susceptibility to alterations in pharmacokinetics and vulnerability to adverse drug reactions.

Chronic conditions may interfere with the elderly person’s ability to distinguish between recent and long-standing ailments. Therefore, the preoperative interview should be conducted in a quiet, relaxed environment with as few distractions as possible. The elderly person should be allowed to respond to each question independently without prompting from a spouse or other family members unless absolutely necessary. This helps maintain the patient’s dignity, independence, and control, which are extremely important to the older adult.

Normal Age-Related Changes.

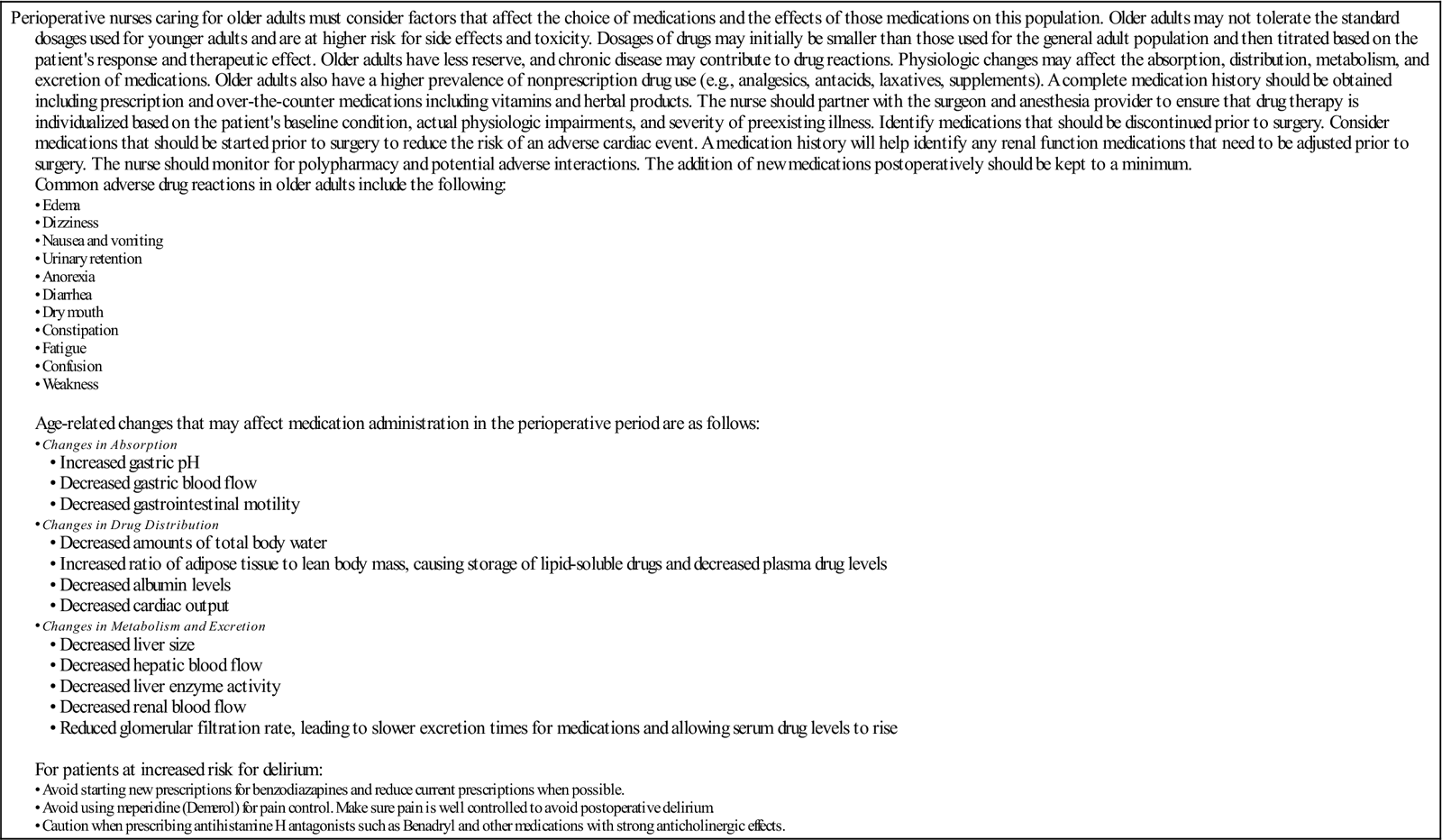

Aging is a biologic process characterized by the inevitable, progressive, predictable evolution and maturation until death. Aging is not the accumulation of disease, although the two are related in subtle, complex ways. A fundamental principle is that biologic age and chronologic age are not the same. Different individuals age at different rates. Physical aging occurs in different organ systems at different rates, influenced by lifestyle choices and socioeconomic status. In general, the aging process imposes a decline in organ functions, atypical responses to pain and temperature, alterations in pharmacokinetics (Surgical Pharmacology), and atypical signs and symptoms of disease, all of which may vary from one elderly person to the next. Having a clear understanding of normal age changes helps establish appropriate nursing diagnoses and develop a plan of care (Box 27-4). The following review of systems focuses on age-specific changes of particular importance to the perioperative plan of care.

Surgical Pharmacology

Medication and the Elderly

| Perioperative nurses caring for older adults must consider factors that affect the choice of medications and the effects of those medications on this population. Older adults may not tolerate the standard dosages used for younger adults and are at higher risk for side effects and toxicity. Dosages of drugs may initially be smaller than those used for the general adult population and then titrated based on the patient’s response and therapeutic effect. Older adults have less reserve, and chronic disease may contribute to drug reactions. Physiologic changes may affect the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of medications. Older adults also have a higher prevalence of nonprescription drug use (e.g., analgesics, antacids, laxatives, supplements). A complete medication history should be obtained including prescription and over-the-counter medications including vitamins and herbal products. The nurse should partner with the surgeon and anesthesia provider to ensure that drug therapy is individualized based on the patient’s baseline condition, actual physiologic impairments, and severity of preexisting illness. Identify medications that should be discontinued prior to surgery. Consider medications that should be started prior to surgery to reduce the risk of an adverse cardiac event. A medication history will help identify any renal function medications that need to be adjusted prior to surgery. The nurse should monitor for polypharmacy and potential adverse interactions. The addition of new medications postoperatively should be kept to a minimum. Common adverse drug reactions in older adults include the following: Age-related changes that may affect medication administration in the perioperative period are as follows: • Changes in Metabolism and Excretion • Decreased hepatic blood flow • Decreased liver enzyme activity For patients at increased risk for delirium: |

Modified from Hodgson BB, Kizior RJ: Saunders nursing drug handbook 2013, St Louis, 2013, Saunders; Ignatavicius DD: Common health problems of older adults. In Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML, editors: Medical-surgical nursing: patient-centered collaborative care, ed 7, St Louis, 2013, Saunders; Chow WB et al: Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society, J Am Coll Surg 215(4):453–466, 2012.

Physiologic Changes

Integumentary System.

The nails become thick and tough related to a decrease of circulation in the hands and feet (Table 27-1). A nick or cut can lead to a serious infection. Color and texture of hair change, and the loss of pigmentation results in graying of hair. Decrease in oil content makes the hair dull and lifeless, and the amount of hair decreases. The skin loses elasticity and subcutaneous fat and becomes more prone to shear force and pressure injury. Because of the thinness of the skin and small-vessel fragility, bruising and hemorrhaging are common. Dry skin develops because of decreased oil and sweat production from sebaceous and sweat glands, respectively (Research Highlight). As a result, skin breakdown and pressure ulcers, as well as wound infections, develop more easily. The vascular system of the skin has nutritional and protective roles. It is necessary for body heat regulation, provides defenses against microbial and physical damage, provides nutrient supply to the avascular epidermis, and promotes wound healing. Having an intact vascular system to maintain these skin role characteristics is extremely important for a patient undergoing surgical intervention. However, papillary capillaries, responsible for epidermal nourishment and heat dissipation, degenerate with aging. What is left is only the horizontal arteriovenous plexus lying beneath the skin surface. This progressive impairment of vascular circulation and tissue nutrition and the loss of subcutaneous tissue predispose to a feeling of cold, especially in cool environments such as the operating room (OR). Therefore, the ability to maintain thermoregulation is compromised in elders and must be controlled through external measures.

TABLE 27-1

| Physiologic Change | Results |

| Decreased vascularity of dermis | Increased pallor in white skin |

| Decreased amount of melanin | Decreased hair color (graying) |

| Decreased sebaceous and sweat gland function | Increased dry skin; decreased sweating |

| Decreased subcutaneous fat | Increased wrinkling |

| Decreased thickness of epidermis | Increased susceptibility to trauma |

| Increased localized pigmentation | Increased prevalence of brown spots (senile lentigo) |

| Increased capillary fragility | Increased purple patches (senile purpura) |

| Decreased density of hair growth | Decreased amount and thickness of hair on head and body |

| Decreased rate of nail growth | Increased brittleness of nails |

| Decreased peripheral circulation | Increased longitudinal ridges on nails, increased thickening and yellowing of nails |

| Increased androgen/estrogen ratio | Increased facial hair in women |

From Wold GH: Basic geriatric nursing, ed 5, St Louis, 2012, Mosby.

Respiratory System.

Pulmonary complications in the elderly account for nearly 50% of postoperative complications in the total population of surgical patients (Wold, 2012). Lungs lose elasticity, which contributes to a decrease in functional residual capacity, residual volume, and dead space. Lungs increase in size and are lighter in weight with aging. A rigid chest wall is the result of calcification of costal cartilages, osteoporosis, and dorsal kyphosis. Muscles responsible for inhalation and exhalation may be weakened, resulting in a diminished ability to increase and decrease the size of the thoracic cavity. All these changes contribute to a minimal tidal exchange, which makes the elderly patient more susceptible to pulmonary complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumonia, and aspiration. Lung changes are not usually obvious at rest. However, when the person becomes active, breathing may be more difficult. The ability to cough and clear the upper airway is lessened, and such reduction may increase the chance of respiratory tract infections and diseases, some of which can be severe enough to be life-threatening.

Cardiovascular System.

A decrease in coronary artery blood flow is more likely in older adults. Because of a shift in blood flow, there is a greater decrease in circulation to the kidneys and liver than to the brain and heart. Blood pressure rises as a result of increased arterial resistance. When the elderly person is at rest, the heart rate remains approximately the same as that of a younger person. However, the older heart requires a longer recovery time after each beat, which means that it reacts poorly to stress and anxiety-produced tachycardia. In general, the capacity of the cardiovascular system to tolerate and buffer insults is limited. Activity, exercise, excitement, and illness increase the body’s need for oxygen and nutrients. The older heart may be unable to meet these needs. Arteries lose their elasticity and become narrow, causing a weakened heart to work harder. As a result, less blood flows through the arteries, causing poor circulation in many parts of the body. Elders have an increased risk for aortic arch disruption, myocardial contusion, and aneurysm development. A complete, comprehensive cardiac workup should be performed before the elderly patient is scheduled for any surgical procedure (Workman, 2013).

Digestive System.

As a person ages digestive glands decrease the amount of secretions; mucus becomes thicker, causing dysphagia; and saliva becomes more alkaline. Loss of teeth or poorly fitted dentures make chewing difficult, resulting in digestion problems. Foods that are difficult to eat are avoided, and such avoidance can affect overall nutrition. Decrease in peristalsis and a reduction of gastric motility—the results of muscle tone loss—cause a delay in stomach emptying. Potential traumatic injuries to the bowel and mesenteric infarction are more likely to occur (Wold, 2012). The absorption of drugs is affected because of a reduction of blood flow to abdominal viscera, a reduction in the amount of hydrochloric acid secreted, and delayed gastric emptying. Decreases in the levels of total body water and plasma volume result in a smaller volume of distribution for water-soluble drugs. Because the percentage of body fat increases and the lean body mass decreases, the storage of lipophilic drugs, such as diazepam and lidocaine, is enhanced. These factors are of particular importance for assessing the patient’s response to preoperative, anesthetic, and postoperative medications.

Urinary System.

Nephrons decrease in function with age, so by 75 years of age a person has probably lost one third to one half of original nephron function. Elasticity and tone are lost in the ureters, bladder, and urethra, which lead to incomplete emptying of the bladder. Benign prostatic hyperplasia is the most common condition in men, with a significant increase in prevalence with age—from 20% in men ages 41 to 60 to 90% in men older than age 80 (Ebersole et al, 2012). Difficulty in voiding and retention of urine are common with this condition. Total bladder capacity also declines, so elderly persons experience a more frequent and urgent need to urinate. Because blood flow to the kidneys is decreased, patients are at greater risk for fluid overload, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and alterations in the elimination of medications. During the perioperative phase of the patient’s hospital stay, the greatest number and variety of drugs are given; the cumulative effect increases the chances for adverse and consequential results.

Musculoskeletal System.

Changes to the elderly person’s skeleton, such as the loss of bone mass, contribute to skeletal instability and make fractures of the hip, rib, distal radius, and vertebrae common. Curvature of the spine and arthritis of the joints are also common. Pain as a fifth vital sign is routinely evaluated for all patients. In elders, long-standing conditions such as arthritis, neuralgia, and ischemic disorders produce chronic pain. Back pain is related to dehydration and decreased flexibility of the vertebral disks. These changes result in a gradual loss of height, loss of strength, and decreased mobility. Poor posture tends to be proportional to the degree of back pain experienced and may greatly compromise internal organ function. Joint range of motion is impaired to varying degrees and may affect surgical positioning. The nurse takes extra care in positioning elderly patients in the OR, ensuring appropriate padding and joint protection (Wold, 2012).

Nervous System.

Although not functionally significant, a steady loss in the number of neurons begins at about 25 years of age. An inappropriate or slow response to stimuli is primarily a result of a decrease in some organ systems’ ability to send reliable messages to the brain and spinal cord. Nerve cells are particularly sensitive to lack of oxygen. Because older adults may have, in varying degrees, cerebral arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis, decreased blood flow and nervous system deficits, such as insomnia, irritability, visual motor deficits, and memory loss, may occur. These patients are more likely to experience subdural hematomas or closed head injuries from falls. Other neurologic changes significant to perioperative care include a loss of position sense in the toes, decreased tactile sense, and atypical response to pain. In addition, aging is associated with disruption of thermoregulation (Wold, 2012); inadvertent hypothermia (temperature less than 96.8° F [36° C]) is a common problem in elders. (See Chapter 5 for a full discussion of preventing unplanned hypothermia in adult surgical patients.) In the OR, maintaining balance between heat gain (e.g., metabolic production, muscular contraction, hot ambient temperature) and heat loss (e.g., radiation, convection, evaporation, ventilation, cold fluid infusion, blood loss, antithermoregulatory drugs, impaired heat production) can be difficult in older surgical patients.

Sensory Changes.

Changes in vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch may influence the patient’s response to care. If preadmission communication is done, the perioperative nurse may ask about vision and hearing and remind patients to bring their glasses and hearing aids to the facility (Clayton, 2008). Farsightedness, or presbyopia, in the aging person is a result of the lens becoming more rigid and less pliable. Consequently, visual acuity and accommodation are decreased. Color perception changes as a result of a yellowing of the lens, which makes distinguishing blue, green, and purple more difficult. Of particular importance in the OR is an awareness of the older person’s difficulty in adapting to changes in light. Moving patients from a dimly lit holding area to the bright lights of the OR can cause momentary “blindness.”

Presbycusis, or loss of hearing sensitivity, is irreversible, bilateral, and primarily sensorineural, although metabolic and mechanical causes are also possible. It is the most frequent cause of hearing loss in the geriatric patient. Hearing loss, which appears to be greater in men than in women, is mostly within the higher frequencies (above 1000 Hz). In addition, cerumen thickens and the eardrum becomes less pliable, and such changes also contribute to diminished hearing. Often geriatric patients are labeled “confused” or “senile” because they respond inappropriately to questions they did not hear or they describe what they see inaccurately because of poor vision.

Changes in taste and smell begin to occur at approximately 60 years of age and become more pronounced with advanced age. Older adults have two to three times more difficulty in detecting flavors than do young adults. Oral hygiene, dental disease, and decreased salivary function may also alter tasting ability. There is a close association between the sense of smell and human behavior. Smell can affect emotions when a person recalls a particular odor. Other functions include protection of the individual by warning of danger in the air, such as smoke or gas fumes; assistance in digestion; and helping a person to remember or recollect. In elders, the sense of smell can be reduced, as well as the ability to identify odors (Wold, 2012).

Changes in sensitivity to touch often accompany the aging process, but the degree of change varies among individuals. In some cases, losses can be related to neuropathy caused by disease, injury, or circulatory problems. Decreased sense of touch can affect the elderly person’s ability to localize stimuli and can reduce the speed of reaction to tactile stimulation. For example, an older person may have difficulty differentiating among coins, fastening buttons, or grasping small items.

Psychologic Changes.

Physiologic and psychologic stress may result in an acute state of confusion or delirium in the geriatric patient that is analogous to convulsions as a stress reaction in the pediatric patient. In elders, mental change can be a warning of some underlying problem. It is of pivotal importance to determine the patient’s interpretation of pain in the assessment phase. Confusion or delirium should therefore not be dismissed as an expected behavior of the geriatric patient. Delirium occurs in more than 80% of intensive care patients and patients at the end of life and in as many as 50% of hospitalized elders (Research Highlight). It is associated with increased length of stay, increased morbidity, poorer functional outcomes, increased risk of nursing home placement, and increased patient care costs. Several studies suggest that delirium is lessened when pain is appropriately managed, as determined in the study by Robinson and colleagues (2008) of hip fracture patients. The most important assessment factor is determining whether the confusion is chronic or acute. Chronic conditions, such as depression and Alzheimer disease, can make communication with the patient difficult. Depending on the stage of disease, patients may not be able to understand explanations. Family members are the best resource to determine the patient’s ability to comprehend and respond to questions and instructions. Behavioral changes such as aggressiveness, agitation, and paranoia are not uncommon. Soft restraints may be necessary during local procedures in the OR to ensure patient safety. Taking the time to talk slowly, being deliberate in movements, getting to know the patient, and developing a trusting relationship before surgery can help to lessen the patient’s anxiety and control the combative outbursts that occur in some Alzheimer patients (Box 27-5). A mnemonic for pain assessment in demented and nonverbal elders is described in Box 27-6. The American Society of Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN) has created guidelines for assessing pain:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree