Genitourinary System

Gladell P. Paner

Tatjana Antic

Jerome B. Taxy

Introduction: Genitourinary Frozen Section

The diagnosis of tumors along the genitourinary tract is best achieved through routine H&E processing using guided access tissue sampling. This more measured sequence maximizes opportunities to consider an appropriate therapeutic approach including the timing of tumor extirpation. For example, the transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided needle core biopsies for prostate cancer and endoscopic diathermy resection or cold-cup biopsy for lesions along the urinary tract have become standard diagnostic approaches (1,2,3,4,5). Complete transurethral resection suffices as therapy for low-grade urothelial tumors. In the kidney and the testis, pre- or intraoperative tumor typing is uncommon since only exceptionally does tumor histology modify the course of the surgical procedure.

The above notwithstanding and considering the limited number of clinically relevant indications, frozen section requests related to the genitourinary organs are frequent. Intraoperative consultations are requested: (i) to ensure tumor resection adequacy (i.e., margin status), (ii) to evaluate stage (infrequent), and (iii) to confirm tumor with or without cell typing. Even so, the use of frozen section in these circumstances varies among institutions and may relate more to practice habits than implementation of an accepted treatment algorithm. Inconsistent action by surgeons to the results of a frozen section may generate inconsistent treatment results.

Currently, changes in frozen section requests may be influenced by the increasing use of robotic-assisted or laparoscopic surgeries for prostate, bladder, and kidney tumors. The questions principally involve tumor cell typing and adequacy of margins, both of which have direct implications on the conduct of a given procedure. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy has now overtaken retropubic radical prostatectomy as the most common surgery performed for prostate cancer (6,7). Open partial nephrectomy is now considered the standard therapy for small organ-confined renal tumors (8). Although performed on limited basis, other procedures which may result in frozen section requests include innovative procedures such as partial cystectomy for localized solitary urothelial carcinoma, diverticular tumors, or urachal carcinoma (9,10); urethral-sparing orthotopic urinary diversion in women (11,12,13,14); testicular organ preservation

surgery (15); and rarely, modifying lymph node sampling in bladder carcinoma (16) and penile carcinoma (17,18). The advent of minimally invasive ablative therapy for smaller renal tumors has brought about an increase in CT-guided needle core biopsy of the kidney mass (19,20,21). Although not recommended, a frozen section may be requested of a core biopsy before renal tumor ablation if no histology is preoperatively available. However, a specific cell type diagnosis of an eosinophilic kidney tumor may be risky if a nephrectomy is at stake.

surgery (15); and rarely, modifying lymph node sampling in bladder carcinoma (16) and penile carcinoma (17,18). The advent of minimally invasive ablative therapy for smaller renal tumors has brought about an increase in CT-guided needle core biopsy of the kidney mass (19,20,21). Although not recommended, a frozen section may be requested of a core biopsy before renal tumor ablation if no histology is preoperatively available. However, a specific cell type diagnosis of an eosinophilic kidney tumor may be risky if a nephrectomy is at stake.

The proposed guidelines for handling and reporting various routine genitourinary specimens (22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31) are perhaps more detailed for prostatectomy specimens as provided in consensus statements recently by the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) (22,23). Surgeons and pathologists should be aware of the advantages as well as the technical and diagnostic limitations of frozen section in order to agree on the necessary information to proceed with the operation. A primary frozen section diagnosis of penile carcinoma; for example, is probably not indicated given the serious consequences.

Adrenal tumors are also seldom submitted for frozen section, because the outcome of the frozen section is unlikely to change the operative procedure. Adrenal cortical tumors are either small enough to be encompassed by an adrenalectomy, are thus unlikely to be considered malignant preoperatively and not a candidate for a wider, more radical resection, or are large and clinically obvious, possibly inoperable. Diagnostic samples from the latter are more amenable to fine needle aspiration and/or needle core biopsy and examined after conventional fixation and embedding. Cortical tumors of intermediate size with potentially indeterminate histologic features are likely to be deferred. Among adrenal medullary tumors, neuroblastoma is discussed in Chapter 7; pheochromocytoma is clinically established prior to surgery is typically a confined tumor, and subject to frozen section only under exceptional circumstances.

This chapter will discuss frozen section as related to common lesions of the kidney, prostate, and urothelium focusing on the urinary bladder. Uncommon situations of testicular, penile, and scrotal frozen sections are also addressed. Reviews of intraoperative consultations for genitourinary specimens have also appeared in the past few years in the clinical literature (32,33,34).

Kidney: Introduction

Primary epithelial tumors of the kidney comprise approximately 3% of all solid neoplasms. The American Cancer Society estimates approximately 64,700 cases in the United States for 2012 with about 13,500 deaths (35). These numbers however, group renal cell carcinomas and carcinomas of the renal pelvis together. SEER data estimates that approximately 80% of the total numbers are renal cell carcinomas and 20% are urothelial carcinomas. Further, SEER data shows an increase in renal cell carcinomas during the years 1975 to 2006 at an annual rate change of 2.9% to 3.6% (36). The

increase may reflect incidental imaging discoveries while pursuing a workup for other unrelated complaints. When tumor characteristics are compared before and after 1991, recent renal tumors tend to be smaller and confined to the kidney (36). As an inadvertent but clinically important consequence, treatment decisions have revisited the traditionally perceived biologic differences between renal cortical neoplasms, adenoma, or renal cell carcinoma, especially the clear cell type, a distinction primarily based on tumor size. Since a solitary renal mass of whatever size discovered incidentally or not is presumed to be malignant and subject to surgical intervention, this distinction ceases to be theoretical and becomes a practical issue for the pathologist in the reporting context of a frozen section.

increase may reflect incidental imaging discoveries while pursuing a workup for other unrelated complaints. When tumor characteristics are compared before and after 1991, recent renal tumors tend to be smaller and confined to the kidney (36). As an inadvertent but clinically important consequence, treatment decisions have revisited the traditionally perceived biologic differences between renal cortical neoplasms, adenoma, or renal cell carcinoma, especially the clear cell type, a distinction primarily based on tumor size. Since a solitary renal mass of whatever size discovered incidentally or not is presumed to be malignant and subject to surgical intervention, this distinction ceases to be theoretical and becomes a practical issue for the pathologist in the reporting context of a frozen section.

Surgical extirpation remains the primary accepted modality for treating renal cell carcinoma, as it has been for more than 50 years. The traditional procedure against which all others are measured is the open radical nephrectomy, that is, a wide excision of the kidney to include the perirenal fat, external investing (Gerota’s) fascia, and adrenal gland (37). In the past, partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma was exceptional (38); however, in recent years, this procedure has become much more widely used. Partial nephrectomy is now the standard therapy for small renal masses (≤4 cm) and has results comparable to radical nephrectomy related to low perioperative morbidity, preservation of renal function, and low local recurrence rate (8,37,39,40,41). Currently, open partial nephrectomy is being challenged by the laparoscopic approach. Both so far appear to have comparable tumor control and renal function results (41).

Kidney: The Intraoperative Questions

Frozen section requests for lesions of the kidney generally focus on three major issues: (i) The identification or confirmation of tumor, (ii) the cell type of the tumor, and (iii) the margin of resection pertaining to partial nephrectomy. With the sophisticated imaging techniques currently available, the preoperative diagnosis of a mass lesion, solid or cystic, is not usually problematic. Percutaneous ultrasound or CT-guided needle biopsy is safe and often provides adequate tissue for workup and diagnosis of renal and pelvicaliceal tumors including most subtypes (19,42,43). When performed, frozen section confirmation of an actual tumor may influence the nature of the surgical procedure with regard to removal of the kidney or, in the case of urothelial carcinoma, to undertake a nephroureterectomy. A benign or nonneoplastic condition may terminate the procedure. The interpretation of these frozen sections may assume greater clinical importance for those tumors close to the hilum or involving the renal pelvis. The cell typing data summarized in Table 9.1 summarizes the University of Chicago experience in both the confirmation of the presence of tumor as well as the cell type.

Nephron-sparing procedures, either open or laparoscopic, may require immediate pathologic evaluation of the parenchymal margin, and frozen section has been increasingly employed for this. The indications for partial nephrectomy have included the following for small renal masses (40):

Table 9.1 Kidney Frozen Sectiona | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Enhancing solid or complex cystic renal mass whenever resection is technically feasible.

Young and fit patients with limited medical comorbidity.

Renal hilar tumors for which ablative therapy is contraindicated.

Indications for nephron-sparing surgery; for example, (i) solitary functional kidney (absolute indication), (ii) potential compromise of the opposite kidney by a condition that might impair renal function in the future (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, glomerulonephritis, reflux, recurrent infection), or (iii) multiple bilateral tumors or hereditary forms of renal carcinoma carrying the risk of future recurrences.

For larger tumors (>4 cm), partial nephrectomy is also feasible and can be performed but only in selected patients (8). In addition to potential complications of the immediate postoperative period, the clinical issues are recurrence related to multifocality and the extent to which recurrence predicts for metastatic disease and overall long-term survival. While multifocality is an issue in approximately 15% of sporadic renal cell carcinomas, occult multifocal tumors below the level of resolution of the imaging studies can obviously not be predicted, including in hereditary renal cancers (44). Nonetheless, survivals between partial and total nephrectomy patients are virtually comparable (37,41,45,46). Based on recurrence rates in the summarized large series of partial nephrectomy, the contribution of multifocal or multicentric tumors to subsequent recurrence or metastasis is probably small (37). Given this current understanding of the biologic behavior of renal cell carcinoma and the need to ensure complete excision of at least the dominant lesion, frozen sections in the context of partial nephrectomies may be reasonable requests. However, following some

experience with this procedure, the frozen section for parenchymal margins has become controversial with more investigators not inclined for its use, as reported margin positivity is low. The histologic status of the parenchymal margin has little apparent impact on long-term oncologic outcome; the surgeon’s gross impression seems reliable (47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54).

experience with this procedure, the frozen section for parenchymal margins has become controversial with more investigators not inclined for its use, as reported margin positivity is low. The histologic status of the parenchymal margin has little apparent impact on long-term oncologic outcome; the surgeon’s gross impression seems reliable (47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54).

Kidney: Frozen Section Examination

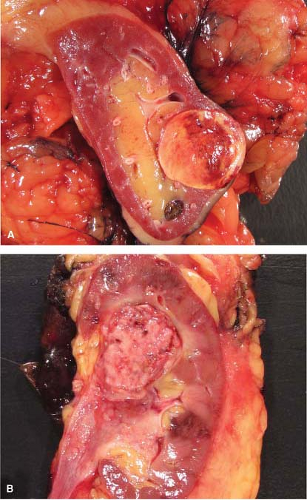

Gross examination of nephrectomy specimens is applicable for relevant tumor distinctions and margin assessment during intraoperative consultation. Whereas histologic subtyping of common renal parenchymal epithelial tumors may not be crucial at the time of nephrectomy, a distinction from urothelial carcinoma impacts the additional removal of the entire ureter. The typical gross pathology of common renal cell carcinoma is a solitary circumscribed lesion and color varies depending on subtype. Urothelial carcinoma in contrast involves or is centered on the pelvicalyceal system, is gray-white, often poorly circumscribed and if invasive, irregularly infiltrates the renal parenchyma. On occasion, gross examination alone may suffice in distinguishing these two tumors (Fig. 9.1).

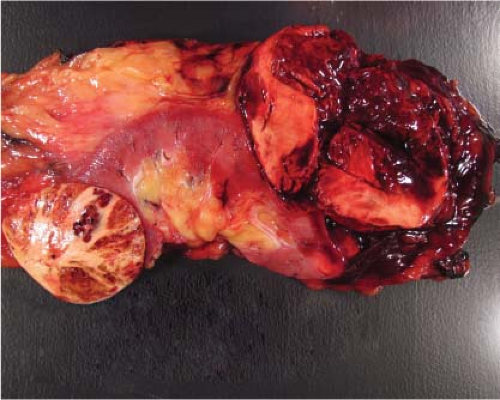

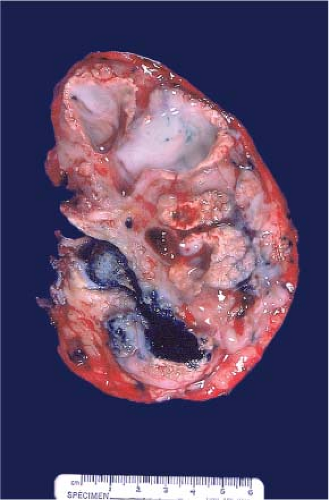

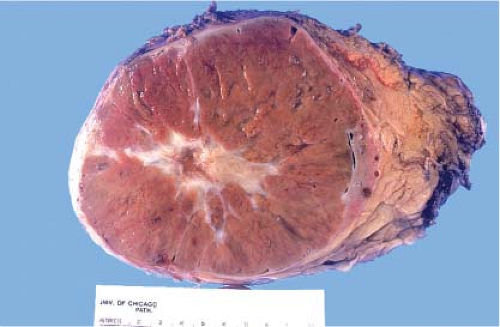

The gross features of renal cell carcinoma vary widely (color, solid or cystic, hemorrhagic, necrotic, extrarenal extension). The common renal epithelial tumors are well circumscribed. Clear cell is often golden yellow (Fig. 9.2), papillary is variegated dark brown (from hemorrhage) to

yellow (presence of macrophages) and sometimes multifocal (Fig. 9.3), and chromophobe varies from beige for classic type (e-Fig. 9.1) to mahogany brown corresponding to the proportion of cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm simulating renal oncocytoma. A central scar is present in one-third of oncocytomas (Fig. 9.4), but is not specific and is also seen in a smaller subset of eosinophilic chromophobe tumors. Firm white-tan fleshy areas may indicate high-grade sarcomatoid change, poor circumscription (e-Fig. 9.2) raises the possibility of a high-grade carcinoma; for example, collecting duct, medullary, urothelial carcinoma, or metastatic tumors. Complete or partially cystic renal cell carcinomas are multiloculated (e-Figs. 9.3 and 9.4). Instead of separate small biopsies being sent, it is optimal if the entire gross specimen with the lesion in place is available for inspection and not incised in the operating room.

yellow (presence of macrophages) and sometimes multifocal (Fig. 9.3), and chromophobe varies from beige for classic type (e-Fig. 9.1) to mahogany brown corresponding to the proportion of cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm simulating renal oncocytoma. A central scar is present in one-third of oncocytomas (Fig. 9.4), but is not specific and is also seen in a smaller subset of eosinophilic chromophobe tumors. Firm white-tan fleshy areas may indicate high-grade sarcomatoid change, poor circumscription (e-Fig. 9.2) raises the possibility of a high-grade carcinoma; for example, collecting duct, medullary, urothelial carcinoma, or metastatic tumors. Complete or partially cystic renal cell carcinomas are multiloculated (e-Figs. 9.3 and 9.4). Instead of separate small biopsies being sent, it is optimal if the entire gross specimen with the lesion in place is available for inspection and not incised in the operating room.

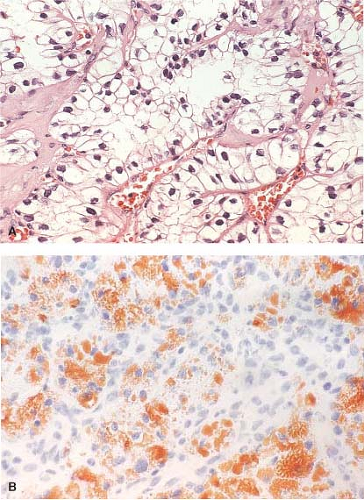

While the histologic identification of specific cell type by frozen section has limited application, the presence of tumor is dependent on the ability to recognize specific cell types. In this regard, clear cell carcinoma is perhaps the most obvious with its characteristic highly vascularized (“chicken-wire”), nested growth of polygonal cells with clear cytoplasm (Fig. 9.5A). The cytoplasmic clarity of this predominant histologic subtype of renal cell carcinoma is due to accumulations of fat and/or glycogen. If the examiner feels the immediate need to further define the cytoplasmic content of a clear cell renal tumor, the presence of fat can be easily assessed at the time of frozen section by doing an Oil Red O stain (Fig. 9.5B). Assessing glycogen requires PAS/PAS-D staining on paraffin material and is not available in a frozen section

setting. Chromophobe carcinomas are recognized by the pale, amphophilic cytoplasm, prominent cytoplasmic membrane, characteristic perinuclear halos, koilocytoid nuclei, and binucleation (e-Figs. 9.5 and 9.6).

setting. Chromophobe carcinomas are recognized by the pale, amphophilic cytoplasm, prominent cytoplasmic membrane, characteristic perinuclear halos, koilocytoid nuclei, and binucleation (e-Figs. 9.5 and 9.6).

Figure 9.4 Renal oncocytoma is typically mahogany brown and often exhibits a central scar. This gross appearance may also be seen in a smaller subset of eosinophilic chromophobe tumors. |

On occasion, because of the eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, it may be difficult to distinguish oncocytoma, eosinophilic chromophobe, and clear cell type with predominant eosinophilic cytoplasm on frozen section.

In such situations, reporting “renal oncocytic neoplasm” with enumeration of the differential diagnosis and deferment of final diagnosis is reasonable since the distinction will have minimal or no influence in the conduct of the surgical procedure.

In such situations, reporting “renal oncocytic neoplasm” with enumeration of the differential diagnosis and deferment of final diagnosis is reasonable since the distinction will have minimal or no influence in the conduct of the surgical procedure.

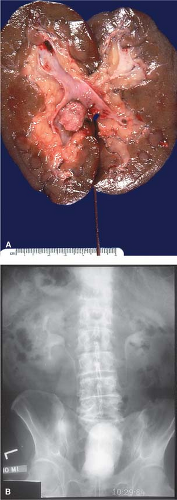

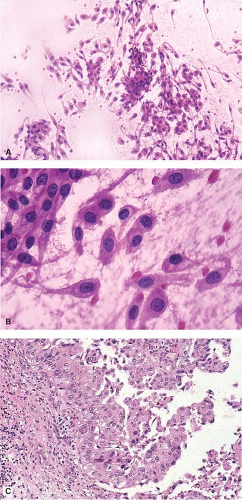

Imprints are underutilized. Figure 9.7A,B illustrate a gross specimen and the corresponding clinical radiograph with an obvious renal pelvic tumor. Imprints from this lesion stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrate syncytia of well-defined polygonal cells with nuclear

pleomorphism, abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, and cytoplasmic processes, features commonly seen in urothelial tumors. These cytologic features (Fig. 9.8A,B) correspond histologically to urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 9.8C) and correlate with the gross examination.

pleomorphism, abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, and cytoplasmic processes, features commonly seen in urothelial tumors. These cytologic features (Fig. 9.8A,B) correspond histologically to urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 9.8C) and correlate with the gross examination.

Figure 9.6 Frozen section of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. The tumor cells show presence of koilocytoid nuclei, perinuclear halo and prominent cytoplasmic membrane. |

Among the 94 cases summarized in Table 9.1 covering a 6½-year period, the only diagnosis of a benign tumor was oncocytoma; a diagnosis of angiomyolipoma was not encountered. There were, however, four discrepant diagnoses (Table 9.2). In one instance, a renal pelvic tumor interpreted by frozen section as an urothelial carcinoma was changed on permanent

section to papillary renal cell carcinoma. The nonclear cell nature of both tumors and the common feature of papillary growth accounted for the erroneous interpretation. Frozen section, like other modalities of morphologic assessment, is not perfect; there are hazards associated with immediate analysis, as this case emphasizes.

section to papillary renal cell carcinoma. The nonclear cell nature of both tumors and the common feature of papillary growth accounted for the erroneous interpretation. Frozen section, like other modalities of morphologic assessment, is not perfect; there are hazards associated with immediate analysis, as this case emphasizes.

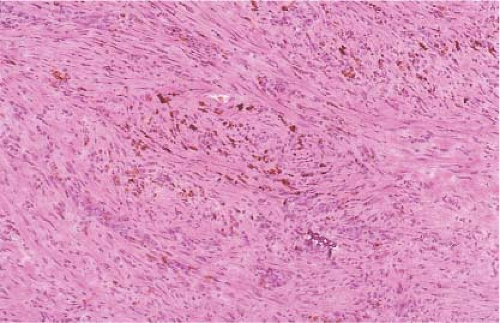

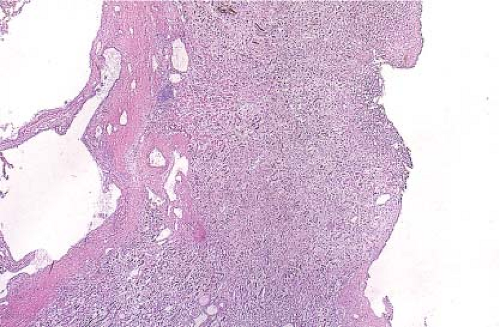

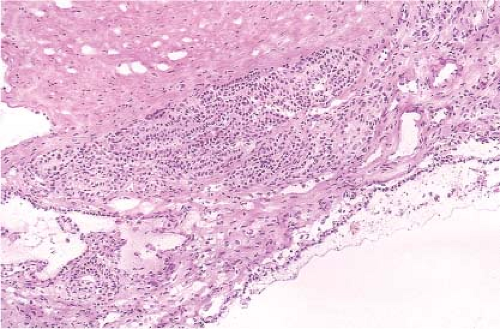

Diagnostic skills are not only challenged in discerning different cell types but in nonneoplastic tumor-like growths as well. Figure 9.9 is a gross photograph of a kidney from a 74-year-old male patient who was evaluated at another hospital with a presumptive diagnosis of a primary renal tumor at least partially affecting the renal pelvis. Upon referral, a laparoscopic nephrectomy was done with some difficulty because of local adhesions and scarring. The gross examination of the bivalved specimen demonstrated multiple grayish and orange-tinged masses of varying size partially involving the renal pelvis with associated calyceal dilatation and hemorrhage. No stones were present. A frozen section was requested to rule out an urothelial carcinoma, which would have necessitated a completion ureterectomy. Microscopically, there were areas of inflammation

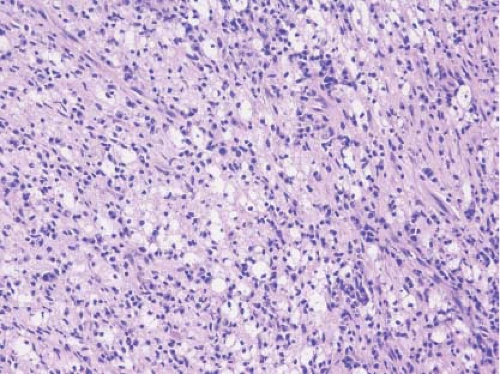

and scarring with some brown pigment. Bits of irregular, blue-stained material suggesting a microlith were also present (Fig. 9.10). In the region of the renal pelvis, frozen section demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with some foamy to clear histiocytes, creating some diagnostic uncertainty related to clear cell renal adenocarcinoma (Fig. 9.11). However, the gross and histologic features were not considered sufficient for a malignant diagnosis and frozen interpretation of probable xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis was reported. This diagnosis was confirmed on examination of permanent material (e-Figs. 9.7–9.9). Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is an unusual, but well-recognized, tumor-like lesion often associated with calculi and with the potential for diffuse organ replacement, extrarenal extension, and macroscopic resemblance to a malignancy (e-Figs. 9.10 and 9.11).

and scarring with some brown pigment. Bits of irregular, blue-stained material suggesting a microlith were also present (Fig. 9.10). In the region of the renal pelvis, frozen section demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with some foamy to clear histiocytes, creating some diagnostic uncertainty related to clear cell renal adenocarcinoma (Fig. 9.11). However, the gross and histologic features were not considered sufficient for a malignant diagnosis and frozen interpretation of probable xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis was reported. This diagnosis was confirmed on examination of permanent material (e-Figs. 9.7–9.9). Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is an unusual, but well-recognized, tumor-like lesion often associated with calculi and with the potential for diffuse organ replacement, extrarenal extension, and macroscopic resemblance to a malignancy (e-Figs. 9.10 and 9.11).

Table 9.2 Frozen Section Discrepant Diagnosesa |

|---|

Partial nephrectomy employs a sharp dissection of adjacent renal parenchyma to yield a rim of normal tissue around the tumor. The optimal amount of normal tissue is not an established figure. Having the entire gross specimen in this circumstance allows the inking of the parenchymal margin before the specimen is freshly cut. Most renal tumors are distinct from the homogenous dark brown tincture of renal parenchyma and gross

assessment alone can be sufficient, only to take sections for frozen section when in doubt. The question of whether to take a “strip” margin or a representative section perpendicular to the inked edge at the point closest to the tumor has never been formally addressed. A perpendicular section may be better because the tissue section can then be taken from the point at which the tumor macroscopically most closely approaches the specimen edge. Given that the possible sources of confusion in this setting include sampling, detached atypical cells, crush artifact, and the misidentification of normal renal tubules for tumor (55,56), having secure gross landmarks is helpful. On occasion, the surgeon may decide to submit a separate biopsy from the tumor bed as the partial nephrectomy margin. One study, however, suggested that entire specimen gross examination with or without frozen section is more sensitive in detecting margin positivity when compared to tumor bed biopsy (75% vs. 25%) (57). Ideally, the surgeon should identify the true margin side by suture or ink and the tissue submitted en face.

assessment alone can be sufficient, only to take sections for frozen section when in doubt. The question of whether to take a “strip” margin or a representative section perpendicular to the inked edge at the point closest to the tumor has never been formally addressed. A perpendicular section may be better because the tissue section can then be taken from the point at which the tumor macroscopically most closely approaches the specimen edge. Given that the possible sources of confusion in this setting include sampling, detached atypical cells, crush artifact, and the misidentification of normal renal tubules for tumor (55,56), having secure gross landmarks is helpful. On occasion, the surgeon may decide to submit a separate biopsy from the tumor bed as the partial nephrectomy margin. One study, however, suggested that entire specimen gross examination with or without frozen section is more sensitive in detecting margin positivity when compared to tumor bed biopsy (75% vs. 25%) (57). Ideally, the surgeon should identify the true margin side by suture or ink and the tissue submitted en face.

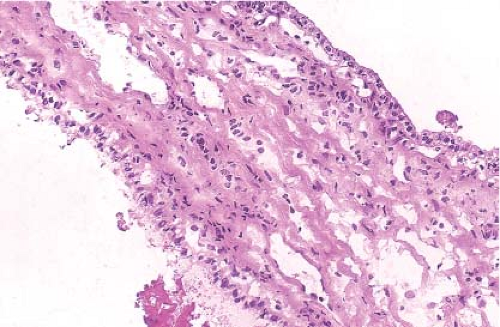

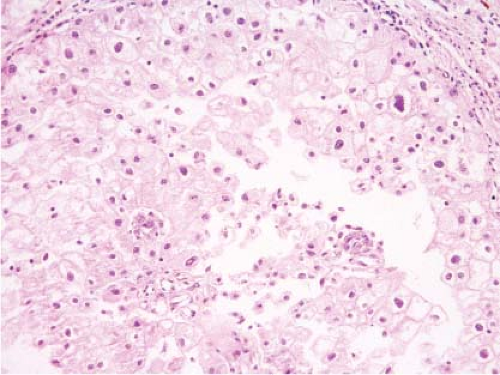

Figure 9.12 illustrates a partial nephrectomy specimen from a patient with compromised renal function. This approximately 3-cm multiloculated cystic mass was removed in the usual fashion with what was grossly apparent as a very thin parenchymal margin. The frozen section sample should be taken from the closest margin after the tissue edge is marked with ink. Figures 9.13–9.15 are from a grossly similar case. The low-power examination demonstrates the cyst locules and a definite rim of normal renal parenchyma (Fig. 9.13). Further examination of the cyst walls demonstrates fibrous septations surfaced on both sides by a bland, but definite clear cell population of polygonal cells (Fig. 9.14). In other areas, presence

of tumor cells in the septae was apparent (Fig. 9.15). A diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma with clear margins can be made, and the operation terminated.

of tumor cells in the septae was apparent (Fig. 9.15). A diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma with clear margins can be made, and the operation terminated.

Urothelial Carcinoma: Introduction

Urothelium is the most primitive of epithelia, both in its organization and in its individual cytologic characteristics. The simplicity of the cytoplasmic organization aptly suits the cells for fluid transport (58). In the past, this

epithelium has been termed “transitional” epithelium, perhaps related to its transport function or possibly because of its ability under inflammatory and neoplastic conditions to demonstrate squamous and/or glandular differentiation. It is now accepted that these cells are not transitional in the sense they represent some intermediate phase of differentiation but do in fact represent a discrete form of epithelium. Hence, the current designation as urothelium.

epithelium has been termed “transitional” epithelium, perhaps related to its transport function or possibly because of its ability under inflammatory and neoplastic conditions to demonstrate squamous and/or glandular differentiation. It is now accepted that these cells are not transitional in the sense they represent some intermediate phase of differentiation but do in fact represent a discrete form of epithelium. Hence, the current designation as urothelium.

Figure 9.15 Frozen section. Another area showing a tumor locule lined by clear cells with a microscopic area of infiltration beneath. |

The individual cell simplicity is also reflected in the histologic organization, since basal to surface maturation is subtle. The integrity and recognition of this organization is essential to the interpretation of a frozen section. A key feature in the histologic assessment of urothelial organization is the preservation of the basal and suprabasal (intermediate) cell layers. Ideally, the basal cells have a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and a palisaded arrangement. The suprabasilar cells are more loosely arranged with minor increases in cytoplasm and slightly elongated or ovoid nuclei. These layers may only be a few cells in thickness. The ovoid nuclei normally point toward the top (polarity); however, this orientation may not be preserved from distortion of frozen section. The presence of surface “umbrella cells,” expansile cell processes, and marked accumulations of cytoplasm, in the most superficial urothelial layer, is not a reliable indicator of a normal maturation sequence since umbrella cells may persist over dysplastic urothelium.

Urothelial Carcinoma: Intraoperative Questions

The pathobiology of urothelial carcinoma is linked to the multifocality or “field effect” inherent in its clinical manifestations. Although urothelial neoplasms occur from the renal pelvis to the bladder, perhaps, the best examples of the frozen section issues in the intraoperative management of urothelial

carcinoma are represented in the urinary bladder. A mass lesion may be accompanied by other similar lesions with grossly uninvolved intervening mucosa, the urothelium may be diffusely involved, or clinically inapparent intramucosal malignancy may be part of a process for which there is a dominant mass lesion (Figs. 9.16–9.18). In the past, radical cystectomy has been done when the tumor is both high grade and muscle invasive (e-Figs. 9.12–9.14). Those clinical criteria may be changing, so that radical cystectomy with curative intent may be undertaken for less than deeply invasive disease.

carcinoma are represented in the urinary bladder. A mass lesion may be accompanied by other similar lesions with grossly uninvolved intervening mucosa, the urothelium may be diffusely involved, or clinically inapparent intramucosal malignancy may be part of a process for which there is a dominant mass lesion (Figs. 9.16–9.18). In the past, radical cystectomy has been done when the tumor is both high grade and muscle invasive (e-Figs. 9.12–9.14). Those clinical criteria may be changing, so that radical cystectomy with curative intent may be undertaken for less than deeply invasive disease.

The major question related to surgical resection of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder is the presence of carcinoma at the proximal ureteral margins. It would be safe to say that the use of frozen section for ureteral margin assessment is currently at least controversial and possibly not indicated (59,60,61,62,63,64,65). While there is an understandable proscription related to cutting through invasive tumor, the examination of ureteral margins focuses on the detection of carcinoma not grossly apparent and confined to the mucosa. Frozen section examination of ureteral margins has been clinically justified on the supposition that high-grade dysplasia is predictive for local recurrence and the development of upper tract tumors. Several studies spanning more than 20 years have indicated that frozen sections of ureteral margins during a radical cystectomy exhibit carcinoma (and/or dysplasia) in up to approximately 9% of ureters (or 13% of patients) (59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67).

However, the role of frozen section of ureter margins is questioned for the following reasons: (i) although the presence of carcinoma at the ureteral margin increases the risk upper tract recurrences, the probability is low (4.9% to 17%) and not associated with survival (63,65,67); (ii) although

specificity of frozen section for ureter margin is high (up to 99%), it only has the modest sensitivity at 45% to 75% (61,64,65

specificity of frozen section for ureter margin is high (up to 99%), it only has the modest sensitivity at 45% to 75% (61,64,65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree