INTRODUCTION

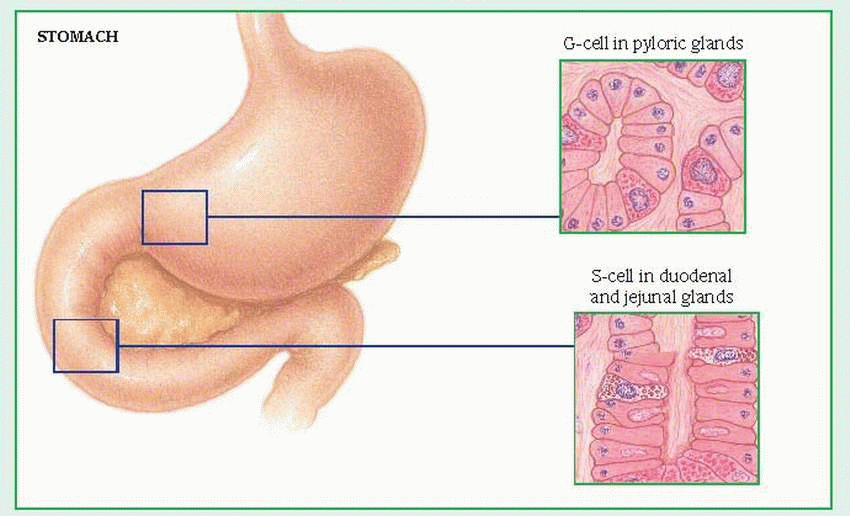

The GI tract, also known as the

alimentary canal, is a long, hollow, musculomembranous tube consisting of glands and accessory organs (salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas). (See

Reviewing GI anatomy and physiology. See also

Histology of the GI tract,

page 216.) The GI tract breaks down food—carbohydrates, fats, and proteins—into molecules small enough to permeate cell membranes, thus providing cells with the necessary energy to function properly; it prepares food for cellular absorption by altering its physical and chemical composition. (See

Primary source of digestive hormones,

page 217.) Consequently, a malfunction along the GI tract can produce far-reaching metabolic effects, eventually threatening life itself. The GI tract is an unsterile system filled with bacteria and other flora; these organisms can cause superinfection from antibiotic therapy or they can infect other systems when a GI organ ruptures. A common indication of GI problems is referred pain, which makes diagnosis especially difficult.

ACCURATE ASSESSMENT VITAL

Your assessment of the patient with suspected GI disease must begin with a careful history that includes occupation, family history, and recent travel. The medical history should include previous hospital admissions; surgical procedures (including recent tooth extraction); family history of ulcers, colitis, liver disease, or cancer; and current medications, whether prescribed, over-the-counter, or herbal remedies, with particular attention to aspirin, steroids, and anticoagulants. In addition, assess for food or drug allergies.

Have the patient describe his chief complaint in his own words. Does he have abdominal pain, indigestion, heartburn, or rectal bleeding? How long has he had it? What relieves these symptoms or makes them worse? Has he experienced nosebleeds or difficulty in swallowing recently? Has he had recent weight loss or gain? Is he on a special diet? Does he drink alcoholic beverages or smoke? If yes to either, how much and how often? Ask about bowel habits. Does he regularly use laxatives or enemas? If he experiences nausea and vomiting, what does the vomitus look like? Does changing his position relieve nausea?

Next, try to define and locate any pain. Ask the patient to describe the pain. Is it dull, sharp, burning, aching, spasmodic, or intermittent? Where is it located? Does it radiate? How long does it last? When does it occur? What triggers it? What relieves it?

VISUAL ASSESSMENT

Observe how the patient looks, and note appropriateness of behavior. Changes in fluid and electrolyte balance, severe infection, drug toxicity, and hepatic disease may cause abnormal behavior. Your visual examination should check:

Skin—loss of turgor, jaundice, cyanosis, pallor, diaphoresis, petechiae, bruises, edema, and texture (dry or oily)

Head—color of sclerae, sunken eyes, dentures, caries, lesions, tongue (color, swelling, dryness), and breath odor

Chest—shape (asymmetrical, barrel, or sunken)

Lungs—rate, rhythm, and quality of respirations

Abdomen—size and shape (distention, contour, visible masses, and protrusions), abdominal scars or fistulae, excessive skin folds (may indicate wasting), and abnormal respiratory movements (inflammation of diaphragm)

AUSCULTATION, PALPATION, AND PERCUSSION

Auscultation provides helpful clues to GI abnormalities and should always be performed before palpation and percussion to avoid altering the assessment. For example, absence of bowel sounds over the area to the lower right of the umbilicus may indicate peritonitis. High-pitched sounds that coincide with colicky pain may indicate small-bowel obstruction. Less intense, low-pitched rumbling noises may accompany minor irritation.

Palpating the abdomen after auscultation helps detect tenderness, muscle guarding, and abdominal masses. Watch for muscle tone (boardlike rigidity points to peritonitis or hemorrhage; transient rigidity suggests severe pain) and tenderness (rebound tenderness may indicate peritoneal inflammation).

Percussion helps detect air, fluid, and solid matter in the abdominal region.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

After physical assessment, several tests can identify GI malfunction.

A barium or gastrografin swallow is used primarily to examine the esophagus. Gastrografin may be used instead of barium. Like barium, gastrografin facilitates X-ray imaging. However, if gastrografin escapes from the GI tract, it’s absorbed by the surrounding tissue, whereas escaped barium isn’t absorbed and can cause complications.

In an upper GI series, swallowed barium sulfate travels through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum to reveal abnormalities. The barium outlines stomach walls and delineates ulcer craters and defects.

A small-bowel series, an extension of the upper GI series, visualizes barium flowing through the small intestine to the ileocecal valve.

A barium enema (lower GI series) allows X-ray visualization of the colon.

A stool specimen is useful to detect suspected GI bleeding, infection, or malabsorption as well as the presence of parasites. Guaiac test

for occult blood, microscopic stool examination for ova and parasites, and tests for fat require several specimens.

In esophagogastroduodenoscopy, insertion of a fiber-optic scope allows direct visual inspection of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. These structures are examined for varices, tumors, inflammation, hernias, polyps, ulcers, and obstruction.

Proctosigmoidoscopy permits inspection of the rectum and distal sigmoid colon; colonoscopy is used for inspection of the descending, transverse, and ascending colon. These tests help visualize tumors, polyps, hemorrhoids, or ulcers.

Gastric analysis examines gastric secretions for the presence of high levels of gastrin and the amount of acid produced.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) directly visualizes the esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, and fluoroscopically visualizes the pancreatic, hepatic, and biliary ducts. This test can help visualize duct obstruction, benign structures, cysts, anatomic variations, and malignant tumors. ERCP can be used to relieve or remove obstructions of the biliary tree.

INTUBATION

Certain GI disorders require nasogastric (NG) intubation to empty the stomach and intestine, to aid diagnosis and treatment, to decompress obstructed areas, to detect and treat GI bleeding, and to administer medications or feedings. Tubes generally inserted through the nose are the short NG tubes (the Levin, the Salem Sump, and the specialized Sengstaken-Blakemore) and the long intestinal tubes (Cantor and Miller-Abbott). The larger Ewald tube is usually inserted orally.

When caring for the patient with a tube:

Explain the procedure before intubation.

Maintain accurate intake and output records. Measure gastric drainage every 8 hours; record the amount, color, odor, and consistency. When irrigating the tube, note the amount of saline solution instilled and aspirated. Check for fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Provide good oral and nasal care. Brush the patient’s teeth frequently and provide mouthwash. Make sure that the tube is secure, but isn’t causing pressure on the nostrils. Change the tape to the nose every 24 hours. Gently wash the area around the tube, and apply a water-soluble lubricant to soften

crusts. These measures help prevent sore throat and nose, dry lips, nasal excoriation, and parotitis.

Ensure maximum patient comfort. After insertion of a long intestinal tube, instruct the patient to turn from side to side to facilitate its passage through the GI tract. Note the tube’s progress. Never attach an intestinal tube to a patient’s gown, bed linens, side rails of the bed, and so forth.

With both types of tubes, tell the patient to expect a feeling of dryness or a lump in the throat; if he’s allowed, suggest that he chew gum or eat hard candy to relieve discomfort.

Always keep scissors taped to the wall near the bed when the patient has a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in place. If the tube should dislodge and obstruct the bronchus, cut the lumen to the balloons immediately. Sometimes the tube is taped to the face piece of a football helmet worn by the patient to prevent the tube from dislodging and to put traction on the tube.

After removing the tube from a patient with GI bleeding, watch for signs and symptoms of recurrent bleeding, such as hematemesis, decreased hemoglobin level, pallor, chills, diaphoresis, hypotension, and rapid pulse.

Provide emotional support because the patient may panic at the sight of a tube. A calm, reassuring manner can help minimize his fear.

MOUTH AND ESOPHAGUS

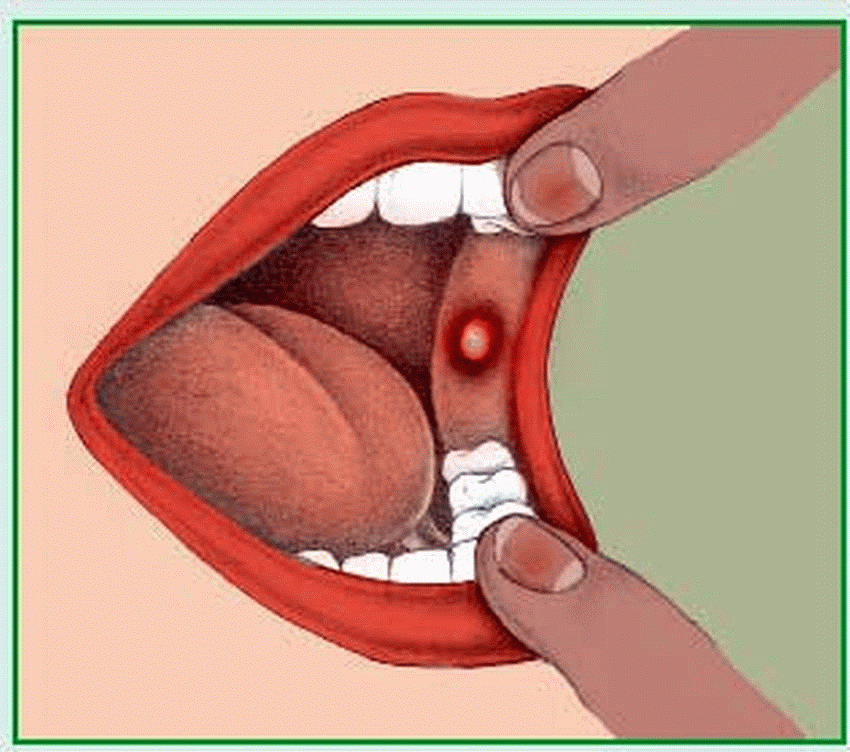

Stomatitis and other oral infections

Stomatitis is an inflammation of the oral mucosa that may extend to the buccal mucosa, lips, and palate. It’s a common infection that may occur alone or as part of a systemic disease. There are two main types: acute herpetic stomatitis and aphthous stomatitis. Acute herpetic stomatitis is usually self-limiting; however, it may be severe and, in neonates, may be generalized and potentially fatal. Aphthous stomatitis, also known as

canker sores, usually heals spontaneously, without a scar, in 10 to 14 days. It may be an extra-intestinal symptom of irritable bowel disease. Other oral infections include gingivitis, candidiasis, glossitis, periodontitis, and Vincent’s angina. (See

Types of oral infections.)

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Acute herpetic stomatitis results from the herpes simplex virus. It’s common in children ages 1 to 3. The cause of aphthous stomatitis is unknown, but predisposing factors include stress, fatigue, anxiety, febrile states, trauma, and solar overexposure. This type is common in young and teenage girls.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Acute herpetic stomatitis begins suddenly with mouth pain, malaise, lethargy, anorexia, irritability, and fever, which may persist for 1 to 2 weeks. Gums are swollen and bleed easily, and the mucous membrane is extremely tender.

Papulovesicular ulcers appear in the mouth and throat and eventually become punched-out lesions with reddened areolae. Submaxillary lymphadenitis is common. Pain usually disappears 2 to 4 days before healing of ulcers is complete. If the child with stomatitis sucks his thumb, these lesions spread to the hand.

A patient with aphthous stomatitis typically reports burning, tingling, and slight swelling of the mucous membrane. Single or multiple shallow ulcers with whitish centers and red borders appear and heal at one site and then reappear at another. (See

Looking at aphthous stomatitis,

page 220.)

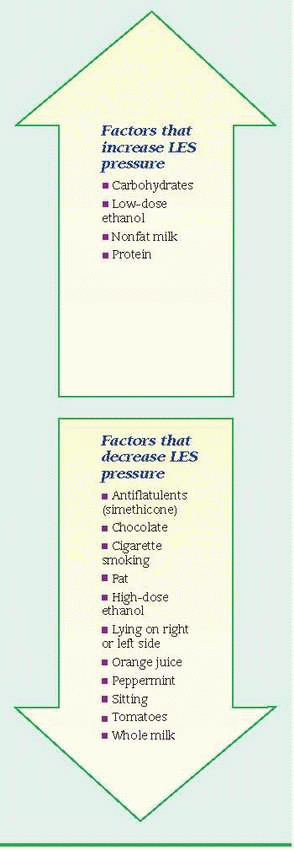

Gastroesophageal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux, also called gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), is the backflow of gastric or duodenal contents, or both, into the esophagus and past the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) without associated belching or vomiting. Reflux may cause symptoms or pathologic changes. Persistent reflux may cause reflux esophagitis (inflammation of the esophageal mucosa). Prognosis varies with the underlying cause.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The function of the LES—a high-pressure area in the lower esophagus, just above the stomach—is to prevent gastric contents from backing up into the esophagus. Normally, the LES creates pressure, closing the lower end of the esophagus, but relaxes after each swallow to allow food into the stomach. Reflux occurs when LES pressure is deficient or when pressure within the stomach exceeds LES pressure. (See

Influences on LES pressure.)

Studies have shown that a patient with symptom-producing reflux can’t swallow often enough to create sufficient peristaltic amplitude to clear gastric acid from the lower esophagus. This results in prolonged periods of acidity in the esophagus when reflux occurs.

Predisposing factors include:

pyloric surgery (alteration or removal of the pylorus), which allows reflux of bile or pancreatic juice

long-term nasogastric (NG) intubation (more than 4 days)

any agent that lowers LES pressure, such as food, alcohol, cigarettes, anticholinergics (atropine, belladonna, and propantheline), or other drugs (morphine, diazepam, calcium channel blockers, and meperidine)

hiatal hernia with an incompetent sphincter

any condition or position that increases intraabdominal pressure, such as straining, bending, coughing, pregnancy, obesity, and recurrent or persistent vomiting

About 25% to 40% of Americans experience symptomatic GERD at some point in their lives, and 7% to 10% of Americans experience symptoms on a daily basis. True incidence figures may be even higher because many people with GERD take over-the-counter remedies without reporting their symptoms.

Studies show that GERD is common and may be overlooked in infants and children. It can cause repeated vomiting, coughing, and other respiratory problems. An immature digestive system is usually responsible, and most infants grow out of GERD by the time they are age 1.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

GERD doesn’t always cause symptoms, and in patients showing clinical effects, it isn’t always possible to confirm physiologic reflux. The most common feature of GERD is heartburn, which may become more severe with vigorous exercise, bending, or lying down, and may be relieved by antacids or sitting upright. The pain of esophageal spasm resulting from reflux esophagitis tends to be chronic and may mimic angina pectoris, radiating to the neck, jaws, and arms.

Other symptoms include odynophagia, which may be followed by a dull substernal ache

from severe, long-term reflux; dysphagia from esophageal spasm, stricture, or esophagitis; and bleeding (bright red or dark brown). Nocturnal regurgitation can awaken the patient with coughing, choking, and a mouthful of saliva. Reflux may be associated with hiatal hernia. Direct hiatal hernia becomes clinically significant only when reflux is confirmed.

Pulmonary symptoms result from reflux of gastric contents into the throat and subsequent aspiration; they include chronic pulmonary disease or nocturnal wheezing, bronchitis, asthma, morning hoarseness, and cough. In children, other signs consist of failure to thrive and forceful vomiting from esophageal irritation. Such vomiting sometimes causes aspiration pneumonia.

Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia

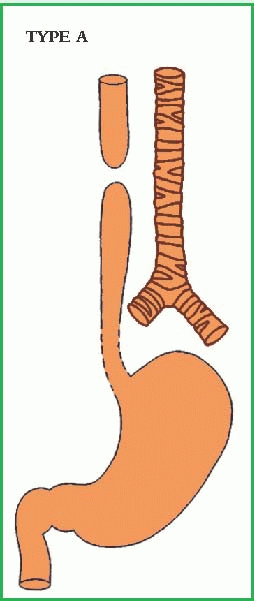

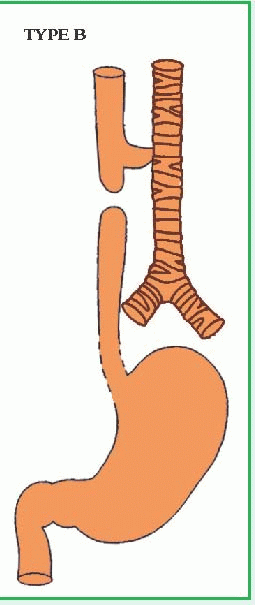

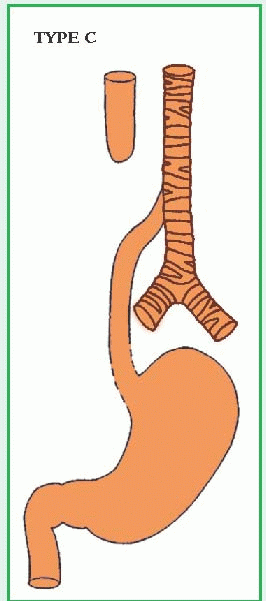

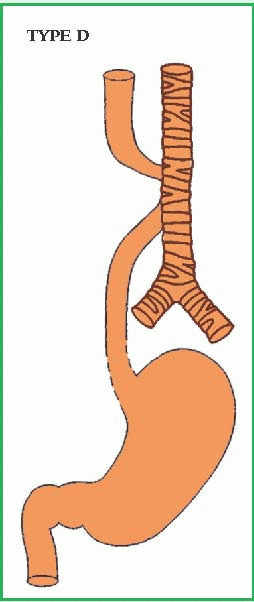

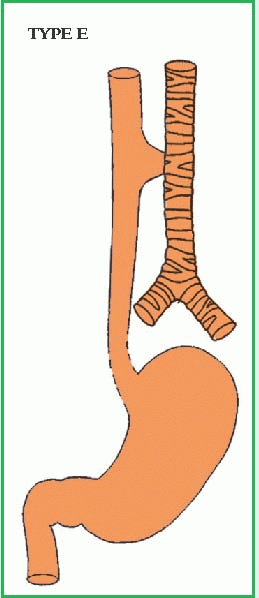

Tracheoesophageal fistula is a developmental anomaly characterized by an abnormal connection between the trachea and the esophagus. It usually accompanies esophageal atresia, in which the esophagus is closed off at some point. Although these malformations have numerous anatomic variations, the most common, by far, is esophageal atresia with fistula to the distal segment. (See

Types of tracheoesophageal anomalies,

pages 224 and 225.)

These disorders, two of the most serious surgical emergencies in neonates, require immediate diagnosis and correction. They may coexist with other serious anomalies, such as congenital heart disease, imperforate anus, genitourinary abnormalities, and intestinal atresia.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia result from failure of the embryonic esophagus and trachea to develop and separate correctly. Respiratory system development begins at about day 26 of gestation. Abnormal development of the septum during this time can lead to tracheoesophageal fistula. The most common abnormality is type C tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, in which the upper section of the esophagus terminates in a blind pouch, and the lower section ascends from the stomach and connects with the trachea by a short fistulous tract.

In type A atresia, both esophageal segments are blind pouches, and neither is connected to the airway. In type E (or H-type), tracheoesophageal fistula without atresia, the fistula may occur anywhere between the level of the cricoid cartilage and the midesophagus, but is usually higher in the trachea than in the esophagus. Such a fistula may be as small as a pinpoint. In types B and D, the upper portion of the esophagus opens into the trachea; neonates with this anomaly may experience life-threatening aspiration of saliva or food.

Esophageal atresia occurs in about 1 of every 1,500 to 3,500 live births; about one third of these neonates are born prematurely.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

A neonate with type C tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia appears to swallow normally but soon after swallowing coughs, struggles, becomes cyanotic, and stops breathing as he aspirates fluids returning from the blind pouch of the esophagus through his nose and mouth. Stomach distention may cause respiratory distress; air and gastric contents (bile and gastric secretions) may reflux through the fistula into the trachea, resulting in chemical pneumonitis.

An infant with type A esophageal atresia appears normal at birth. The infant swallows normally, but as secretions fill the esophageal sac and overflow into the oropharynx, he develops mucus in the oropharynx and drools excessively. When the infant is fed, regurgitation and respiratory distress follow aspiration. Suctioning the mucus and secretions temporarily relieves these symptoms. Excessive secretions and drooling in the neonate strongly suggest esophageal atresia.

Repeated episodes of pneumonitis, pulmonary infection, and abdominal distention may signal type E (or H-type) tracheoesophageal fistula. When a child with this disorder drinks, he coughs, chokes, and becomes cyanotic. Excessive mucus builds up in the oropharynx. Crying forces air from the trachea into the esophagus, producing abdominal distention. Because such a child may appear normal at birth, this type of tracheoesophageal fistula may be overlooked, and diagnosis may be delayed as long as 1 year.

Type B (proximal fistula) and type D (fistula to both segments) cause immediate aspiration of saliva into the airway and bacterial pneumonitis.

Corrosive esophagitis and stricture

Corrosive esophagitis is inflammation and damage to the esophagus after ingestion of a caustic chemical. Similar to a burn, this injury may be temporary or may lead to permanent stricture (narrowing or stenosis) of the esophagus that’s correctable only through surgery. Severe injury can quickly lead to esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and death from infection, shock, and massive hemorrhage (due to aortic perforation).

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The most common chemical injury to the esophagus follows the ingestion of lye or other strong alkali; ingestion of strong acids is less common. The type and amount of chemical ingested determine the severity and location of the damage. In children, household chemical ingestion is accidental; in adults, it’s usually a suicide attempt or gesture. The chemical may damage only the mucosa or submucosa or it may damage all layers of the esophagus.

Esophageal tissue damage occurs in three phases: the acute phase, consisting of edema and inflammation; the latent phase, with ulceration, exudation, and tissue sloughing; and the chronic phase, in which there is diffuse scarring.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease accounts for 70% to 80% of all cases of esophageal stricture. Postoperative strictures account for 10% of all cases, and corrosive strictures account for less than 5% of all cases. Peptic strictures are 10 times more common in Whites than in Blacks and Asians and two to three times more common in men than in women.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Effects vary from none at all to intense pain and edema in the mouth, anterior chest pain, marked salivation, inability to swallow, and tachypnea. Bloody vomitus containing pieces of esophageal tissue signals severe damage. Signs of esophageal perforation and mediastinitis, especially crepitation, indicate destruction of the entire esophagus. Inability to speak implies laryngeal damage.

The acute phase subsides in 3 to 4 days, enabling the patient to eat again. Fever suggests secondary infection. Symptoms of dysphagia return if stricture develops, usually within weeks; rarely, stricture is delayed and develops several years after the injury.

Mallory-Weiss syndrome

Mallory-Weiss syndrome is mild to massive, usually painless bleeding due to a tear in the mucosa or submucosa of the cardia or lower esophagus. Such a tear, usually singular and longitudinal, results from prolonged or forceful vomiting. Sixty percent of these tears involve the

cardia; 15%, the terminal esophagus; and 25%, the region across the esophagogastric junction.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Forceful or prolonged vomiting can cause esophageal tearing when the upper esophageal sphincter fails to relax during vomiting; this lack of sphincter coordination seems more common after excessive alcohol intake. Other factors that can increase intra-abdominal pressure and predispose a person to this type of tear include coughing, straining during bowel movements, traumatic injury, seizures, childbirth, hiatal hernia, esophagitis, gastritis, and atrophic gastric mucosa.

Mallory-Weiss syndrome accounts for 1% to 15% of all cases of upper GI bleeding. It’s two to four times more common in men than in women. There’s no racial predilection. Patients usually present with symptoms during their 40s and 50s, but it can affect people of all ages.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Mallory-Weiss syndrome typically begins with vomiting of blood or passing large amounts of blood rectally a few hours to several days after forceful vomiting. The bleeding, which may be accompanied by epigastric or back pain, may range from mild to massive, but is usually more profuse than in esophageal rupture. In Mallory-Weiss syndrome, the blood vessels are only partially severed, preventing retraction and closure of the lumen.

Esophageal diverticula

Esophageal diverticula are hollow outpouchings of one or more layers of the esophageal wall. They occur in three main areas: just above the upper esophageal sphincter (Zenker’s, or pulsion, diverticulum, the most common type); near the midpoint of the esophagus (traction diverticulum); and just above the lower esophageal sphincter (epiphrenic diverticulum). Generally, esophageal diverticula occur later

in life—although they can affect infants and children—and are three times more common in men than in women. Epiphrenic diverticula usually occur in middle-aged men, whereas Zenker’s diverticula typically affect men older than age 60.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Esophageal diverticula are due to primary muscular abnormalities that may be congenital or to inflammatory processes adjacent to the esophagus. Zenker’s diverticulum occurs when the pouch results from increased intraesophageal pressure; traction diverticulum occurs when the pouch is pulled out by adjacent inflamed tissue or lymph nodes. Some authorities classify all diverticula as traction diverticula.

Zenker’s diverticulum results from developmental muscular weakness of the posterior pharynx above the border of the cricopharyngeal muscle. The pressure of swallowing aggravates this weakness, as does contraction of the pharynx before relaxation of the sphincter. A midesophageal (traction) diverticulum is a response to scarring and pulling on esophageal walls by an external inflammatory process such as tuberculosis. An epiphrenic diverticulum (rare) is generally right-sided and usually accompanies an esophageal motor disturbance, such as esophageal spasm or achalasia. It’s thought to be caused by traction and pulsation.

Most diverticula occur in middle-aged and elderly patients. Zenker’s diverticula occur most commonly in patients older than age 50 and are especially prevalent in patients in their 70s and 80s.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Midesophageal and epiphrenic diverticula with an associated motor disturbance (achalasia or spasm) seldom produce symptoms, although the patient may experience dysphagia and heartburn. Zenker’s diverticulum, however, produces distinctly staged symptoms, beginning with initial throat irritation followed by dysphagia and near-complete obstruction. In early stages, regurgitation occurs soon after eating; in later stages, regurgitation after eating is delayed and may even occur during sleep, leading to food aspiration and pulmonary infection.

Other signs and symptoms include noise when liquids are swallowed, chronic cough, hoarseness, a bad taste in the mouth or foul breath and, rarely, bleeding.

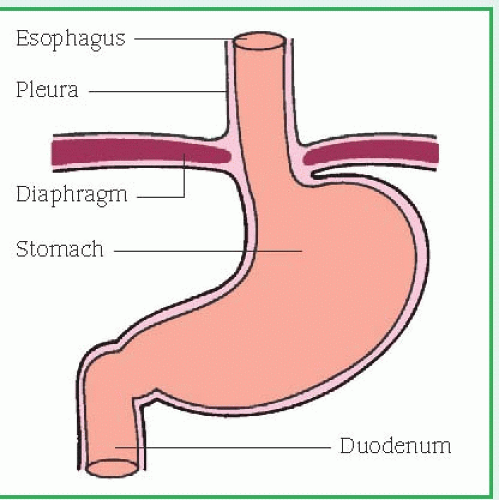

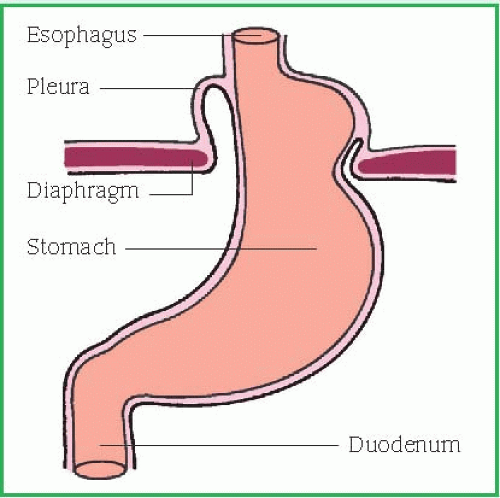

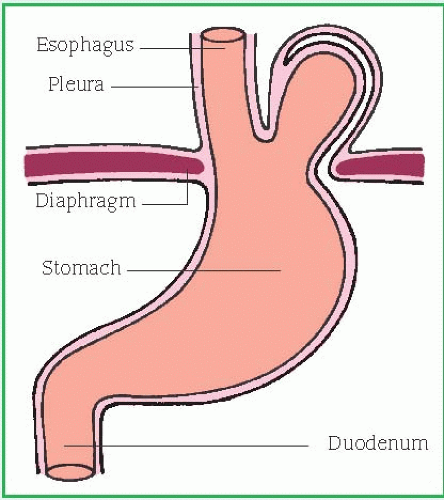

Hiatal hernia

Hiatal hernia, also called

hiatus hernia, is a defect in the diaphragm that permits a portion of the stomach to pass through the diaphragmatic opening into the chest. Hiatal hernia is the most common problem of the diaphragm affecting the alimentary canal. Two types of hiatal hernia can occur: sliding hernia and paraesophageal hernia. (See

Types of hiatal hernia.) In a sliding hernia, the stomach and the gastroesophageal junction slip up into the chest, so the gastroesophageal junction is above the diaphragmatic hiatus. In paraesophageal hernia, a part of the greater curvature of the stomach rolls through the diaphragmatic defect. Treatment can prevent complications such as strangulation of the herniated intrathoracic portion of the stomach.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Hiatal hernia typically results from muscle weakening that’s common with aging and may be secondary to esophageal carcinoma, kyphoscoliosis, trauma, or certain surgical procedures. It may also result from certain diaphragmatic malformations that may cause congenital weakness. Obesity and smoking are common risk factors.

In hiatal hernia, the muscular collar around the esophageal and diaphragmatic junction loosens, permitting the lower portion of the esophagus and the stomach to rise into the chest when intra-abdominal pressure increases (possibly causing gastroesophageal reflux). Such increased intra-abdominal pressure may result from ascites, pregnancy, obesity, constrictive clothing, bending, straining, coughing, Valsalva’s maneuver, or extreme physical exertion.

Sliding hernias are more common than paraesophageal hernias. The incidence of hiatal hernia increases with age (most occur in people older than age 40), and prevalence is higher in women than in men (especially the paraesophageal type). Contributing factors include obesity and trauma.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Typically, a paraesophageal hernia produces no symptoms; it’s usually an incidental finding during a barium swallow or when testing for occult blood. Because this type of hernia leaves the closing mechanism of the cardiac sphincter unchanged, it rarely causes acid reflux or reflux esophagitis. Symptoms result from displacement or stretching of the stomach and may include a feeling of fullness in the chest or pain resembling angina pectoris. Even if it produces no symptoms, this type of hernia needs surgical treatment because of the high risk of strangulation that can occur when a large portion of stomach becomes caught above the diaphragm.

A sliding hernia without an incompetent sphincter produces no reflux or symptoms and, consequently, doesn’t require treatment. When a sliding hernia causes symptoms, they are typical of gastric reflux, resulting from the incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and may include the following:

Pyrosis (heartburn) occurs 1 to 4 hours after eating (especially overeating) and is aggravated by reclining, belching, and increased intraabdominal pressure. It may be accompanied by regurgitation or vomiting.

Retrosternal or substernal chest pain results from reflux of gastric contents, stomach distention, and spasm or altered motor activity. Chest pain usually occurs after meals or at bedtime and is aggravated by reclining, belching, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Other common symptoms reflect possible complications:

Dysphagia occurs when the hernia produces esophagitis, esophageal ulceration, or stricture, especially with ingestion of very hot or cold foods, alcoholic beverages, or a large amount of food.

Bleeding may be mild or massive, frank or occult; the source may be esophagitis or erosions of the gastric pouch.

Severe pain and shock result from incarceration, in which a large portion of the stomach is caught above the diaphragm (usually occurs with paraesophageal hernia). Incarceration may lead to perforation of the gastric ulcer and strangulation and gangrene of the herniated portion of the stomach. It requires immediate surgery.

STOMACH, INTESTINE, AND PANCREAS

Gastritis

Gastritis, an inflammation of the gastric mucosa, may be acute or chronic. Acute gastritis produces mucosal reddening, edema, hemorrhage, and erosion. Chronic gastritis is common among elderly people and people with pernicious anemia. It typically occurs as chronic atrophic gastritis, in which all stomach mucosal layers are inflamed, with reduced numbers of chief and parietal cells. Acute or chronic gastritis can occur at any age.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Acute gastritis has numerous causes, including:

chronic ingestion of (or an allergic reaction to) irritating foods or beverages, such as hot peppers or alcohol

drugs, such as aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (in large doses), cytotoxic agents, corticosteroids, antimetabolites, phenylbutazone, and indomethacin

ingestion of poisons, especially DDT, ammonia, mercury, carbon tetrachloride, and corrosive substances

endotoxins released from infecting bacteria, such as staphylococci, Escherichia coli, or salmonella

Acute gastritis leading to stress ulcers also may develop in acute illnesses, especially when the patient has had major traumatic injuries; burns; severe infection; hepatic, renal, or respiratory failure; or major surgery.

Chronic gastritis may be associated with peptic ulcer disease or gastrostomy, both of which cause chronic reflux of pancreatic secretions, bile, and bile acids from the duodenum into the stomach. Recurring exposure to irritating substances, such as drugs, alcohol, cigarette smoke, or environmental agents, may also lead to chronic gastritis. Chronic gastritis may occur with pernicious anemia, renal disease, or diabetes mellitus. Pernicious anemia is commonly associated with atrophic gastritis, a chronic inflammation of the stomach resulting from degeneration of the gastric mucosa. In pernicious anemia, the stomach can no longer secrete intrinsic factor, which is needed for vitamin B12 absorption.

Bacterial infection with Helicobacter pylori is a common cause of nonerosive chronic gastritis. About 35% of adults are infected with H. pylori, but the prevalence of H. pylori infection is much higher in minority groups and in immigrants. Children ages 2 to 8 in developing nations acquire the infection at a rate of 10% per year; in the United States, the rate of yearly infection is less than 1 %.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

After exposure to the offending substance, the patient with acute gastritis typically reports a rapid onset of symptoms, such as epigastric discomfort, indigestion, cramping, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and hematemesis. The symptoms last from a few hours to a few days.

The patient with chronic gastritis may describe similar symptoms or may have only mild epigastric discomfort, or his complaints may be vague, such as an intolerance for spicy or fatty foods or slight pain relieved by eating. The patient with chronic atrophic gastritis may be asymptomatic.

Gastroenteritis

A self-limiting disorder, gastroenteritis is characterized by diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and acute or chronic abdominal cramping. Also called intestinal flu, traveler’s diarrhea, viral enteritis, or food poisoning, it occurs in persons of all ages and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in underdeveloped nations. In the United States, gastroenteritis ranks second to the common cold as a leading cause of lost work time and fifth as the leading cause of death among young children. It also can be lifethreatening in elderly or debilitated people.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Gastroenteritis has many possible causes, including:

bacteria (responsible for acute food poison ing), such as

Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella, Shigella, Clostridium botulinum, C. perfringens, and

Escherichia coli

amebae, especially Entamoeba histolytica

parasites, such as Ascaris, Enterobius, and Trichinella spiralis

viruses (may be responsible for traveler’s diarrhea) such as adenoviruses, echoviruses, or coxsackieviruses

ingestion of toxins, including plants or toadstools

drug reactions; for example, to antibiotics

enzyme deficiencies

food allergens

The bowel reacts to any of these enterotoxins with hypermotility, producing severe diarrhea and secondary depletion of intracellular fluid. Chronic gastroenteritis is usually the result of another GI disorder such as ulcerative colitis.

Diarrhea accounts for as many as 3% of pediatric office visits and 10% of hospitalizations for patients younger than age 5. Each year, gastroenteritis affects many adults and accounts for 8 million physician visits and 250,000 hospitalizations. Traveler’s diarrhea affects 20% to 25% of people traveling from industrialized countries to developing countries.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the pathologic organism and on the level of GI tract involved. However, gastroenteritis in adults is usually an acute, self-limiting, nonfatal disease producing diarrhea, abdominal discomfort (ranging from cramping to pain), nausea, and vomiting. Other possible signs and symptoms include fever, malaise, and borborygmi. In children, the elderly, and the debilitated, gastroenteritis produces the same symptoms, but these patients’ intolerance to electrolyte and fluid losses leads to a higher mortality.