Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Infants and Children

George W. Holcomb, III

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common diseases requiring surgical correction in infants and children. Its symptoms include persistent vomiting (reflux), failure to thrive and weight loss, aspiration pneumonia, and apnea/bradycardia events (near-SIDS episodes). These symptoms occur primarily in infants and young children. In older children, the symptoms are similar to those seen in adults and include persistent heartburn, esophagitis and stricture, and, occasionally, Barrett’s esophagus. Many adolescents have been managed medically for several years prior to referral for operative therapy. Neurologic impairment is a significant comorbidity in infants and children. It is difficult to quantify the degree of neurologic impairment with the need for fundoplication. Many neurological impaired children need a gastrostomy due to swallowing dysfunction. In this situation, a concomitant fundoplication should be considered. This is especially true in neonates and young infants in whom it is not clear if their clinical reflux will resolve spontaneously. In older children with neurologic impairment and no evidence of GERD, a gastrostomy alone is not unreasonable.

Physiology

Not all infants with GERD require either medical or surgical management. In fact, the majority of these patients do not require therapy. Twenty years ago, Boix-Ochoa showed that there is a maturation process at the lower esophagus sphincter (LES). In a group of elegant studies in which he evaluated normal infants and children with manometry, he showed that there is a very small length of intra-abdominal esophagus present at birth. However, over the next several months, the length of intra-abdominal esophagus gradually increases. Similarly, he showed that there is a maturation process to the pressure gradient generated by the LES. This maturation of the pressure gradient at the LES corresponds with elongation of the intra-abdominal esophagus. Therefore, infants with marked GERD who do not exhibit any evidence of failure to thrive, apnea/bradycardia, or aspiration pneumonia can be observed to see if their symptoms resolve in the first 6 to 12 months of life.

Pathophysiology

Maturation of LES leads to the development of a barrier against reflux. Unfortunately, this barrier’s function is not always effective in preventing GERD. In adults, LES pressures greater than 30 mm Hg have been shown to prevent reflux, whereas pressures between 0 and 5 mm Hg have resulted in abnormal pH studies consistent with reflux in 80% of the patients. GERD is more likely to develop when the LES pressure is less than 6 mm Hg at the respiratory inversion point, and the overall LES length is less than 2 cm, of which less than 1 cm is intra-abdominal. Moreover, in the patients in whom the LES has not developed properly or with a hiatal hernia, the LES becomes positioned within the chest, which results in loss of its protective function.

LES relaxation occurs normally with esophageal peristalsis and allows one to swallow without discomfort. Inappropriate LES relaxations have been shown to occur sporadically. For a number of years, these transient LES relaxations (TLESRs) have been thought to be the primary mechanism for gastroesophageal reflux in adult patients. Similarly, TLESRs have been documented as the likely cause for gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children.

Although this barrier function at the LES is highly effective, it is imperfect. A short LES length, TLESRs, location of the LES in the chest, or abnormal smooth muscle function can contribute to the failure of LES, resulting in gastroesophageal reflux. Moreover, disruption of the LES secondary to a hiatal hernia, abnormal LES function, or previous esophageal surgery can also result in poor function and subsequent reflux.

A second barrier that has been shown to prevent reflux is the intra-abdominal length (IAL) of the lower esophagus. An IAL of greater than 3 cm in adults with normal abdominal pressure has been shown to provide LES competency 100% of the time, whereas an IAL of less than 1 cm results in significant reflux. The importance of the IAL of the lower esophagus as a barrier to preventing reflux in adults cannot be overemphasized. Whether or not there is a similar minimum IAL in infants and children remains unclear and is discussed later.

Another impediment to reflux is created by the angle of His. Although the precise functional component of the angle of His is not well known, when this angle becomes more obtuse, reflux is more likely to develop. Conversely, accentuation of the angle of His inhibits reflux. In all fundoplication techniques, this angle of His is made more acute. On the other hand, an obtuse angle can develop following the placement of a gastrostomy because the fundus of the stomach is often relocated more caudad when the body of the stomach is brought up to the anterior abdominal wall.

The final barrier to reflux is often an important factor when considering operative therapy in adults, but is rarely significant in children. The ability of the esophagus to clear lumenal contents effectively may be diminished with impaired esophageal motility as a result of abnormal smooth muscle function, impaired vagal stimulation, or obstruction from an esophageal stricture. Although an assessment of esophageal motor function is important in adults, it is rarely necessary in children who have no history of a smooth muscle disorder.

As has been previously mentioned, most infants with gastroesophageal reflux do not require operative correction. Indications for fundoplication in infants include an apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) episode, weight loss and growth failure, the neurologically impaired child who requires a gastrostomy, and the child who develops aspiration pneumonia. In the patients under six months of age, in our experience, the most common indication for fundoplication is admission to the hospital for an ALTE episode. In a report of 81 infants between 2000 and 2005 undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication for ALTE, all but three patients had previously been treated with anti-reflux medication. Moreover, 71 infants (87.7%) were on anti-reflux medicines at the time of their ALTE. The median follow-up was 1738 days. After fundoplication, only three patients (3.7%) experienced another ALTE. Two required a re-do laparoscopic fundoplication and one underwent pyloromyotomy for pyloric stenosis. None experienced a recurrent ALTE.

For the patients between 2 and 5 years of age, the most common indication is failure to grow appropriately. For those patients older than 5 years of age, the most common reason for operation is failure of medical management. Included in these two older groups are patients with pulmonary symptoms such as severe refractory airway disease and recurrent aspiration pneumonia. Throughout all these age ranges, however, the neurologically impaired child who requires gastrostomy is often seen. It is the author’s opinion that a neurologically impaired child older than 1 or 2 years of age who requires gastrostomy for poor oral intake but does not exhibit symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux should undergo gastrostomy alone, realizing that a small percentage will subsequently require fundoplication, but the majority will not. The more difficult question is in the infant with neurological impairment who requires gastrostomy. As alluded to previously, in this patient, fundoplication is usually recommended because of concern about protecting the airway from aspiration due to reflux.

Prior to referral to a pediatric surgeon, a pH study often has been performed. This study measures acid reflux and has a sensitivity around 90%. Although it has been assumed that the retrograde flow of acid from the stomach into the esophagus is a basic event in pathologic reflux disease, newer information indicates that alkaline reflux is quite common as well. This information comes from multichannel intraluminal impedance (MMI), which measures the flow of gastric contents into the esophagus by detecting decreases in impedance from high (the esophagus) to low (the stomach) values across electrode pairs that are placed throughout the esophagus and stomach. Recent studies using MII suggest that the pH study may not be the best method of evaluating reflux disease as it only measures acid reflux, and many reflux episodes are actually non-acid reflux with a pH greater than four. Therefore, MMI is being increasingly used to evaluate reflux disease in infants and children. Other tests that are used in children include endoscopy with biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage with evaluation of the lipid-laden macrophage index and, more recently, the pepsin content.

An upper gastrointestinal contrast study is often used to define the anatomy and ensure that there is no evidence of distal obstruction causing the symptoms. In a recent report from our group, malrotation was found unexpectedly in 4% of the patients scheduled for fundoplication. It should not be used for diagnostic purposes as it has a sensitivity of only 30% to 50%. A gastric emptying study is usually not performed as a routine part of the preoperative evaluation in children. The reason is that fundoplication has been shown to enhance gastric emptying. Thus, it is difficult to interpret an abnormal gastric emptying study prior to fundoplication. In the author’s experience, the gastric emptying study is only used in the rare patient in whom there is a strong suspicion of gastroparesis. However, it is a routine part of the evaluation for either recurrent symptoms or in the patient who needs a second operation. If there is evidence of delayed gastric emptying prior to a second procedure, then pyloroplasty should be considered. Certainly, for a patient undergoing a third operation, pyloroplasty is recommended. As mentioned previously, esophageal motility disorders are rarely seen in pediatric patients. Thus, esophageal manometry is infrequently used prior to fundoplication.

Operative Concerns in Infants and Children

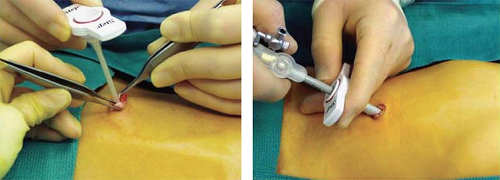

A number of operative concerns are peculiar to infants and children. The first concern is safe entry into the abdominal cavity. For this reason, the Veress needle technique is not recommended and the Step system (Covidien, Norwalk, CT) is preferred, especially for infants and young children. When using this system, after incising the center of the umbilical skin and fascia, the expandable sheet without the Veress needle is introduced directly into the peritoneal cavity. A cannula with a blunt tip trocar is then inserted through the sheath (Fig. 1). With this technique, the underlying organs are not injured with a sharp stylet or needle.

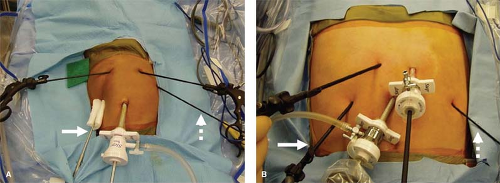

For many operations, including fundoplication, because of the thin abdominal wall in infants and young children, it is possible to place the working instruments directly through the abdominal wall rather than using accessory cannulas (Fig. 2). This is especially advantageous for the instruments

that will not be exteriorized and then reintroduced into the abdominal cavity. In addition to fundoplication, it can also be used for pyloromyotomy, splenectomy, esophagomyotomy, pull-through for Hirschsprung disease, and other procedures. With this stab incision technique, the number of cannulas needed is reduced, resulting in significant cost savings to the institution and the patient.

that will not be exteriorized and then reintroduced into the abdominal cavity. In addition to fundoplication, it can also be used for pyloromyotomy, splenectomy, esophagomyotomy, pull-through for Hirschsprung disease, and other procedures. With this stab incision technique, the number of cannulas needed is reduced, resulting in significant cost savings to the institution and the patient.

Another concern centers on whether to use laparoscopy for fundoplication in patients with congenital heart disease or significant pulmonary disorders. Because of the insufflation pressures required for the laparoscopic approach, there can be a significant reduction in the venous return from the lower extremities, leading to compromised pulmonary blood flow and cardiac deterioration. This is especially true in patients with single-ventricle physiology. The laparoscopic approach may not be advantageous in this group of patients.

An issue peculiar to children is the type of fundoplication that is performed and the use of a bougie to prevent dysphagia when complete fundoplications are performed. The Thal fundoplication is used by a number of pediatric surgeons with good results. In experienced hands, successful repair can be achieved that is comparable to that achieved with the Nissen wrap. The main advantage of the Thal operation is the patient’s ability to burp or belch and the lack of symptomatic dysphagia. At the same time, in the author’s experience, 50% of the patients can burp/belch with an appropriately performed Nissen fundoplication, and the incidence of dysphagia is less than 1%. An appropriate size bougie calibrated for the patient’s weight should be used to prevent narrowing the lower esophagus with a Nissen fundoplication (Table 1).

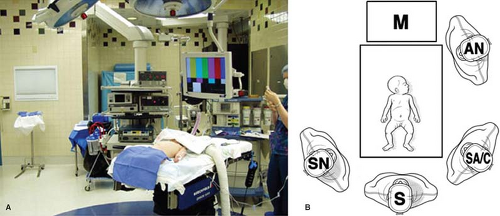

The patient is placed supine on the operating table. Infants and young children are placed at the foot of the table in a frog-leg position (Fig. 3A). The foot of the table is dropped so that the surgeon can stand adjacent to the patient. The operative personnel are positioned as seen in Figure 3B. For older patients in whom this technique is not possible, placement in stirrups is required, with the surgeon standing between the patient’s legs. A urinary catheter is not routinely introduced, but an orogastric tube is important to decompress the stomach during the operation. If a gastrostomy is also required, the site of the gastrostomy is marked in the left upper abdomen prior to insufflation. This site for the gastrostomy will be used for one of the stab incisions for the laparoscopic fundoplication.

Table 1 Recommended Bougie Size for Esophageal Calibration According to Patient Weight | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

A 5-mm incision is made in the umbilical skin and carried down through the umbilical fascia and peritoneum. Often an umbilical hernia is present in infants, enabling easy access to the peritoneal cavity in these small patients. Using the Step system, an expandable sheath is introduced through the umbilical incision into the peritoneal cavity (see Fig. 1). A 5-mm cannula with a blunt trocar is then introduced through the expandable sheath. CO2 insufflation is initiated at a flow rate between 2 and 5 L/min, depending on the patient’s size. A 5-mm, 45-degree angled telescope is inserted and diagnostic laparoscopy is performed.

Four accessory stab incisions are then created (see Fig. 2). The first is in the patient’s right subcostal region, through

which the liver retractor is introduced. The next is in the right epigastric region, through which the instrument used by the surgeon’s left hand is inserted. This is usually an atraumatic grasping forceps. In the patient’s left epigastrium (at the site of previously marked gastrostomy, if needed), another stab incision is made. A Maryland dissecting instrument connected to cautery is introduced through this site for use by the surgeon’s right hand. In the left subcostal region, another stab incision is made through which an atraumatic grasping forceps is placed. This instrument is used by the assistant who is standing on the left side of the operating table (see Fig. 3B).

which the liver retractor is introduced. The next is in the right epigastric region, through which the instrument used by the surgeon’s left hand is inserted. This is usually an atraumatic grasping forceps. In the patient’s left epigastrium (at the site of previously marked gastrostomy, if needed), another stab incision is made. A Maryland dissecting instrument connected to cautery is introduced through this site for use by the surgeon’s right hand. In the left subcostal region, another stab incision is made through which an atraumatic grasping forceps is placed. This instrument is used by the assistant who is standing on the left side of the operating table (see Fig. 3B).

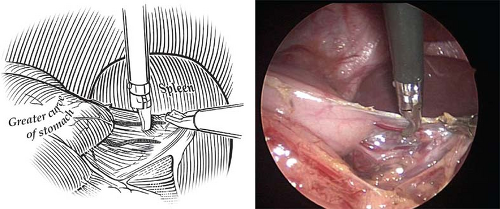

Fig. 4. The first step in performing a laparoscopic fundoplication in an infant is ligation and division of the short gastric vessels. This is accomplished with cautery connected to a Maryland dissecting instrument. Ligation of these vessels is important in infants in order to create a loose, floppy wrap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|