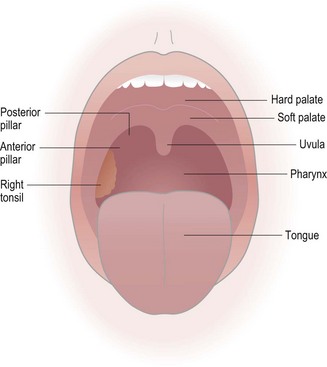

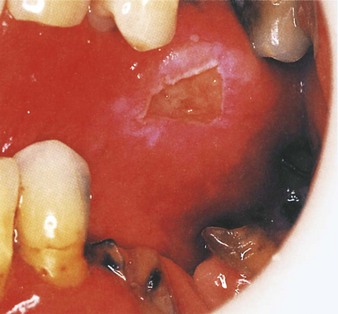

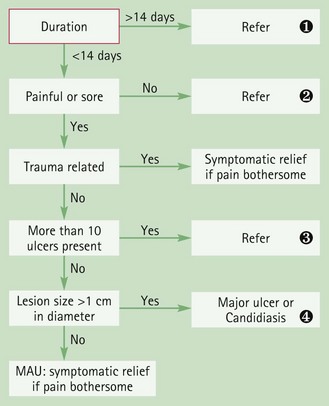

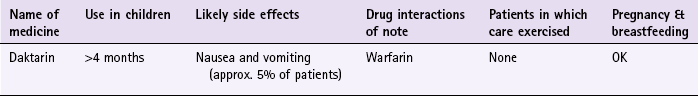

Chapter 6 Background The oral cavity can easily be observed in the pharmacy provided the mouth can be viewed with a good light source, preferably a pen torch (Fig 6.1). The patient will usually present with some form of oral lesion and/or pain in a particular part of the mouth. The pharmacist should examine this area carefully, but the rest of the oral cavity should also be inspected. Checks for periodontal disease (bleeding gums) and other sites of mouth soreness should be performed. There are three main clinical presentations of ulcers: minor, major or herpetiform. Although it is most likely the patient will be suffering from MAU (Table 6.1) it is essential that these and other causes are recognised and referred to the GP for further evaluation. Table 6.1 Causes of ulcers and their relative incidence in community pharmacy A number of ulcer-specific questions should always be asked of the patient (Table 6.2) and an inspection of the oral cavity should also be performed to help aid the diagnosis. Specific questions to ask the patient: Mouth ulcers The ulcers of MAU are roundish, grey-white in colour and painful. They are small – usually less than 1 cm in diameter – and shallow with a raised red rim. Pain is the key presenting symptom and can make eating and drinking difficult, although pain subsides after three or four days. They rarely occur on the gingival mucosa and occur singly or in small crops of up to five ulcers. It normally takes 7 to 14 days for the ulcers to heal but recurrence typically occurs after an interval of 1 to 4 months (Fig. 6.2). Major aphthous ulcers: These are characterised by large (greater than 1 cm in diameter), numerous ulcers, occurring in crops of 10 or more. The ulcers often coalesce to form one large ulcer. The ulcers heal slowly and can persist for many weeks (Fig. 6.3). Trauma: Trauma to the oral mucosa will result in damage and ulceration. Trauma may be mechanical (e.g. tongue biting) or thermal resulting in ulcers with an irregular border. Patients should be able to recall the traumatic event and have no history of similar ulceration or signs of systemic infection (Fig. 6.4). Herpetiform ulcers: Herpetiform ulcers are pinpoint and occur in large crops of up to 100 at a time. They usually heal within a month and often occur in the posterior part of the mouth, an unusual location for MAU (Fig. 6.5). Both herpetiform and major aphthous ulcers are approximately ten times less common than MAU. Oral thrush usually presents as creamy-white soft elevated patches. It is covered in more detail in the next section and the reader is referred to page 139 for differential diagnosis of thrush from other oral lesions. Carcinoma: In 2009, over 6000 cases of oral cancer were confirmed. It is twice as common in men than women. Incidence rates increase sharply beyond 45 years of age. In men the highest incidence is seen in those aged 60–69, and in women it peaks in the over 80s. Smoking and excess alcohol consumption are two major risk factors. Erythema multiforme: Infection or drug therapy can cause erythema multiforme, although in about 50% of cases no cause can be found. Symptoms are sudden in onset causing widespread ulceration of the oral cavity. In addition the patient can have annular and symmetric erythematous skin lesions located toward the extremities. Conjunctivitis and eye pain is also common. Behcet’s syndrome: Most patients will suffer from recurrent, painful major aphthous ulcers that are slow to heal. Lesions are also observed in the genital region and eye involvement (iridocyclitis) is common. Figure 6.6 will aid the differentiation between serious and non-serious conditions that cause mouth ulcers. A wide range of products are used for the temporary relief and treatment of mouth ulcers. These products contain corticosteroids, local anaesthetics, antibacterials, astringents and antiseptics. Until, recently, corticosteroids were available OTC (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% in Orabase and hydrocortisone sodium succinate pellets) but these have been discontinued by the manufacturers. This is unfortunate as a review in BMJ Clinical Evidence found corticosteroids did reduce the duration of pain with MAU (http://exodontia.info/files/BMJ_Clinical_Evidence_2007_Recurrent_Aphthous_Ulcers.pdf; accessed 22 November 2012). Choline salicylate has been shown to exert an analgesic effect in a number of small studies. However, only one study by Reedy (1970) involving 27 patients evaluated choline salicylate in the treatment of oral aphthous ulceration. No significant differences were found between choline salicylate and placebo in ulcer resolution but choline salicylate was found to be significantly superior to placebo in relieving pain. Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for ulcers reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with ulcers are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.1. Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines for ulcers *Children should not be routinely given products as ulcers are rare in this age group. Browne, RM, Fox, EC, Anderson, RJ. Topical triamcinolone acetonide in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. A clinical trial. Lancet. 1968;1:565–567. MacPhee, IT, Sircus, W, Farmer, ED, et al. Use of steroids in treatment of aphthous ulceration. Br Med J. 1968;2(598):147–149. Scully, C. Aphthous ulceration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:165–172. Truelove, SC, Morris-Owen, RM. Treatment of aphthous ulceration of the mouth. Br Med J. 1958;1:603–607. Zakrzewska, JM. Fortnightly review: oral cancer. Br Med J. 1999;318:1051–1054. British Association of Dermatologists. Multi-professional Guidelines for the Management of the Patient with Primary Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. http://www.bad.org.uk/Portals/_Bad/Guidelines/Clinical%20Guidelines/SCC%20Guidelines%20Final%20Aug%2009.pdf, 2009. General site on oral health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/mouthandteeth.html The Behçet’s Syndrome Society. http://www.behcets.org.uk/menus/main.asp The British Dental Health Foundation. http://www.dentalhealth.org.uk/ Oral thrush It is reported that Candida albicans is found in the oral cavity of 30–60% of healthy people in developed countries (Gonsalves et al 2007). Prevalence in denture wearers is even higher. It is transmitted directly between infected people or via objects that can hold the organism. Changes to the normal environment in the oral cavity will allow C. albicans to proliferate. Oral thrush is not difficult to diagnose provided a careful history is taken and an oral examination performed. It is the role of the pharmacist to eliminate underlying pathology and exclude risk factors. A number of other conditions need to be considered (Table 6.4) and specific questions asked of the patient (Table 6.5). After questioning the pharmacist should inspect the oral cavity to confirm the diagnosis. Table 6.4 Causes of oral lesions and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Specific questions to ask the patient: Oral thrush The classical presentation of oral thrush is of creamy-white soft elevated patches that can be wiped off revealing underlying erythematous mucosa (Fig. 6.7). Pain, soreness, altered taste and a burning tongue can be present. Lesions can occur anywhere in the oral cavity but usually affect the tongue, palate, lips and cheeks. Patients sometimes complain of malaise and loss of appetite. In neonates, spontaneous resolution usually occurs but can take a few weeks. Minor aphthous ulcers: Mouth ulcers are covered in more detail on page 134 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of these from oral thrush. Medicine-induced thrush: Inhaled corticosteroids and antibiotics are often associated with causing thrush. In addition, medicines that cause dryness of the mouth can also predispose people to thrush. Always take a drug history to determine if medicines could be a cause of the symptoms. Lichen planus: Lichen planus is a dermatological condition with lesions similar in appearance to plaque psoriasis. In about 50% of people the oral mucous membranes are affected. The cheeks, gums or tongue develop white, slightly raised painless lesions that look a little like a spider’s web. Other symptoms can include soreness of the mouth and a burning sensation. Occasionally, lichen planus of the mouth occurs without any skin rash. Underlying medical disorders: As stated previously, oral thrush is unusual in the adult population. Patients are at greater risk of developing thrush if they suffer from medical conditions such as diabetes, xerostomia (dry mouth) or are immunocompromised. Leukoplakia: Leukoplakia is a predominantly white lesion of the oral mucosa that cannot be characterised as any other definable lesion and is therefore a diagnosis based on exclusion (Fig. 6.8). It is often associated with smoking and is a precancerous lesion, although epidemiological data suggests that annual transformation rate to squamous cell carcinoma is approximately 1%. Patients present with a symptomless white patch that develops over a period of weeks on the tongue or cheek. The lesion cannot be wiped off, unlike oral thrush. Most cases are seen in people over the age of 40; it is more common in men. Suspected cases require referral. Squamous cell carcinoma: Squamous cell carcinoma is covered in more detail on page 137 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of these from oral thrush. Figure 6.9 will aid the differentiation of thrush from other oral lesions. Fig. 6.9 Primer for differential diagnosis of oral thrush. Prescribing information relating to Daktarin Oral gel reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.6; useful tips relating to the application of Daktarin are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.2. Hoppe, JE, Hahn, H. Randomized comparison of two nystatin oral gels with miconazole oral gel for treatment of oral thrush in infants. Antimycotics Study Group. Infection. 1996;24:136–139. Hoppe, JE. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompetent infants: a randomized multicenter study of miconazole gel vs. nystatin suspension. The Antifungals Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:288–293. Parvinen, T, Kokko, J, Yli-Urpo, A. Miconazole lacquer compared with gel in treatment of denture stomatitis. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:361–366. Gingivitis Gingivitis often goes unnoticed because symptoms can be very mild and painless. This often explains why a routine check-up at the dentist reveals more severe gum disease than patients thought they had. A dental history needs to be taken from the patient, in particular details of their tooth brushing routine and technique, as well as the frequency of visits to their dentist. The mouth should be inspected for tell-tale signs of gingival inflammation. A number of gingivitis-specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.7). Specific questions to ask the patient: Gingivitis Put simply, there is no substitute for good oral hygiene. Prevention of plaque build-up is the key to healthy gums and teeth. Twice daily brushing is recommended to maintain oral hygiene at adequate levels. Brushing teeth, with a fluoride toothpaste, to prevent tooth decay, should preferably take place after eating. Flossing is recommended, three times a week, to access areas that a toothbrush might miss. A Cochrane review (Robinson et al 2005) concluded that powered tooth brushes (with rotation oscillation action – where brush heads rotate in one direction and then the other) are more effective than manual brushing at plaque removal. Mouthwashes contain chlorhexidine, hexetidine and hydrogen peroxide. Of these, chlorhexidine in concentrations of either 0.1 or 0.2% has been proven the most effective antibacterial in reducing plaque formation and gingivitis (Ernst et al 1998). In clinical trials it has been shown to be consistently more effective than placebo and comparator medicines, and there appears to be no difference in effect between concentrations. It has even been used as a positive control. Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for gingivitis reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.8; useful tips relating to products for oral care are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.3. Adults and children over 6 years of age should use a 15 mL dose two or three times a day. Ernst, CP, Prockl, K, Willershausen, B. The effectiveness and side effects of 0.1% and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinses: a clinical study. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:443–448. Robinson, P, Deacon, SA, Deery, C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2005. [Art. No.: CD002281. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002281.pub2]. Brecx, M, Brownstone, E, MacDonald, L, et al. Efficacy of Listerine, Meridol and chlorhexidine mouthrinses as supplements to regular tooth cleaning measures. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:202–207. Hase, JC, Ainamo, J, Etemadzadeh, H, et al. Plaque formation and gingivitis after mouthrinsing with 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo for 4 weeks, following an initial professional tooth cleaning. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:533–539. Jones, CM, Blinkhorn, AS, White, E. Hydrogen peroxide, the effect on plaque and gingivitis when used in an oral irrigator. Clin Prev Dent. 1990;12:15–18. Kelly, M. Adult Dental Health Survey: Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: TSO; 2000. Lang, NP, Hase, JC, Grassi, M, et al. Plaque formation and gingivitis after supervised mouthrinsing with 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo for 6 months. Oral Dis. 1998;4:105–113. Maruniak, J, Clark, WB, Walker, CB, et al. The effect of 3 mouthrinses on plaque and gingivitis development. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:19–23. Dyspepsia • non-ulcer dyspepsia/functional dyspepsia (indigestion) • gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD, heartburn) These five conditions represent 90% of dyspepsia cases presented to the GP. In August 2004, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued clinical guidance on the management of dyspepsia in adults in primary care (see web sites at end of section). This guidance has specific information on pharmacist management of dyspepsia. This is still current (July 2012) and specific reference is made to this guidance. Overwhelmingly, patients who present with dyspepsia are likely to be suffering from GORD, gastritis or non-ulcer dyspepsia (Table 6.9). Research has shown that even those patients who meet NICE guidelines for endoscopical investigation are found to have either gastritis/hiatus hernia (30%), oesophagitis (10–17%) or no abnormal findings (30%). It has also been reported that a medical practitioner with an average list size will only see one new case of oesophageal cancer and one new case of stomach cancer every four years. Despite these statistics, a thorough medical and drug history should be taken to enable the community pharmacist to rule out serious pathology. ALARM symptoms (see Trigger points for referral), which would warrant further investigation are surprisingly common and it is important that patients exhibiting these symptoms are referred. A number of dyspepsia specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.10). Table 6.9 Causes of upper GI symptoms and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Specific questions to ask the patient: Dyspepsia Patients with dyspepsia present with a range of symptoms commonly involving: Peptic ulceration: Ruling out peptic ulceration is probably the main consideration for community pharmacists when assessing patients with symptoms of dyspepsia. Ulcers are classed as either gastric or duodenal. They occur most commonly in patients aged between 30 and 50, although patients over the age of 60 account for 80% of deaths even though they only account for 15% of cases. Typically the patient will have well localised mid-epigastric pain described as ‘constant’, ‘annoying’ or ‘gnawing/boring’. In gastric ulcers the pain comes on whenever the stomach is empty, usually 30 minutes after eating and is generally relieved by antacids or food and aggravated by alcohol and caffeine. Gastric ulcers are also more commonly associated with weight loss and GI bleeds than duodenal ulcers. Patients can experience weight loss of 5 to 10 kg and although this could indicate carcinoma, especially in people aged over 40, on investigation a benign gastric ulcer is found most of the time. NSAID use is associated with a three- to fourfold increase in gastric ulcers. Medicine-induced dyspepsia: A number of medicines can cause gastric irritation leading to or provoking GI discomfort or they can decrease oesophageal sphincter tone resulting in reflux. Aspirin and NSAIDs are very often associated with dyspepsia and can affect up to 25% of patients. Table 6.11 lists other medicines commonly implicated in causing dyspepsia. Gastric carcinoma: Gastric carcinoma is the third most common GI malignancy after colorectal and pancreatic cancer. However, only 2% of patients who are referred by their GP for an endoscopy have malignancy. It is therefore a rare condition and community pharmacists are extremely unlikely to encounter a patient with carcinoma. One or more ALARM symptoms should be present plus symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Oesophageal carcinoma: In its early stages, oesophageal carcinoma might go unnoticed. Over time, however, as the oesophagus becomes constricted, patients will complain of difficulty in swallowing and experience a sensation of food sticking in the oesophagus. As the disease progresses weight loss becomes prominent despite the patient maintaining a good appetite. Atypical angina: Not all cases of angina have classical textbook presentation of pain in the retrosternal area with radiation to the neck, back or left shoulder that is precipitated by temperature changes or exercise. Patients can complain of dyspepsia-like symptoms and feel generally unwell. These symptoms might be brought on by a heavy meal. In such cases antacids will fail to relieve symptoms and referral is needed. Figure 6.10 will aid differentiation of the causes of dyspepsia. Fig. 6.10 Primer for differential diagnosis of dyspepsia. A number of trials have compared PPIs with H2 antagonists for non-ulcer dyspepsia and GORD-like symptoms (Moayyedi et al 2006; Talley et al 2002; van Pinxteren 2006). Results indicate that PPIs, even at half the standard POM dose, are generally superior to H2 antagonists in treating dyspeptic symptoms.

Gastroenterology

Conditions affecting the oral cavity

The physical exam

Mouth ulcers

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Minor aphthous ulcers (MAU)

Likely

Major aphthous ulcers, Trauma

Unlikely

Herpetiform ulcers, herpes simplex, oral thrush medicine-induced

Very unlikely

Oral carcinoma, erythema multiforme (Steven’s Johnson syndrome), Behçet’s syndrome

![]() Table 6.2

Table 6.2

Question

Relevance

Number of ulcers

MAU occur singly or in small crops. A single large ulcerated area is more indicative of pathology outside the remit of the community pharmacist

Patients with numerous ulcers are more likely to be suffering from major or herpetiform ulcers rather than MAU

Location of ulcers

Ulcers on the side of the cheeks, tongue and inside of the lips are likely to be MAU

Ulcers located toward the back of the mouth are more consistent with major or herpetiform ulcers

Size and shape

Irregular-shaped ulcers tend to be caused by trauma. If trauma is not the cause then referral is necessary to exclude sinister pathology

If ulcers are large or very small they are unlikely to be caused by MAU

Painless ulcers

Any patient presenting with a painless ulcer in the oral cavity must be referred. This can indicate sinister pathology such as leukoplakia or carcinoma

Age

MAU in young children (<10 years old) is not common and other causes such as primary infection with herpes simplex should be considered

If ulcers appear for the first time after adolescence then the diagnostic probability is increased for them to be caused by things other than MAU

Clinical features of minor aphthous ulcers

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Oral thrush

Very unlikely causes

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

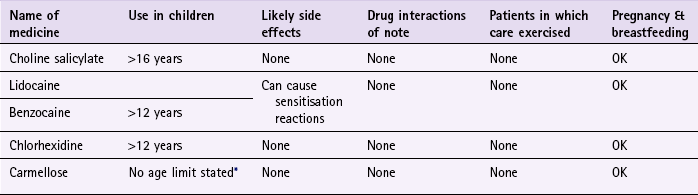

Choline salicylate

Practical prescribing and product selection

![]() Table 6.3

Table 6.3

Aetiology

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Thrush

Likely

Minor aphthous ulcers, medicine induced, ill-fitting dentures

Unlikely

Lichen planus, underlying medical disorders, e.g. diabetes, xerostomia (dry mouth) and immunosuppression, major & herpetiform ulcers, herpes simplex

Very Unlikely

Leukoplakia, squamous cell carcinoma

![]() Table 6.5

Table 6.5

Question

Relevance

Size and shape of lesion

Typically, patients with oral thrush present with ‘patches’. They tend to be irregularly shaped and vary in size from small to large

Associated pain

Thrush usually causes some degree of discomfort or pain. Painless patches, especially in people aged over 50, should be referred to exclude sinister pathology such as leukoplakia

Location of lesions

Oral thrush often affects the tongue and cheeks, although if precipitated by inhaled steroids the lesions appear on the pharynx

Clinical features of oral thrush

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

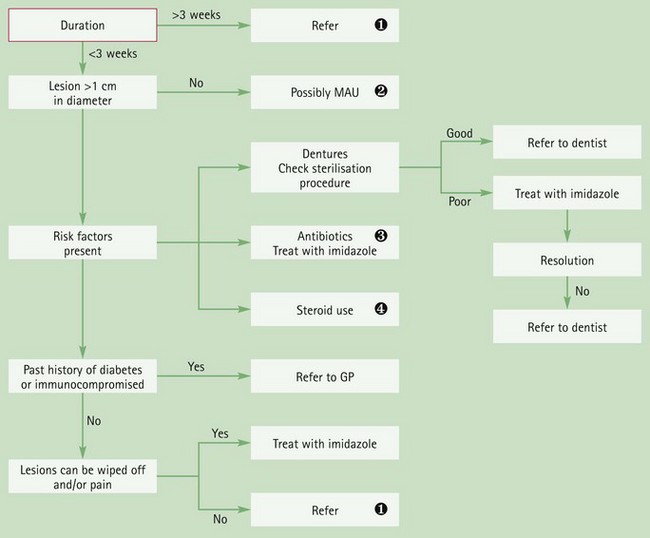

![]() Duration

Duration

Any lesion lasting more than 3 weeks must be referred to exclude sinister pathology.![]() MAU

MAU

See Figure 6.6 for primer for differential diagnosis of mouth ulcers.![]() Antibiotics

Antibiotics

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, e.g. amoxicillin and macrolides, can precipitate oral thrush by altering normal flora of the oral cavity.![]() Inhaled corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids

High-dose inhaled corticosteroids can cause oral thrush. Patients should be encouraged to use a spacer and wash their mouth out after inhaler use to minimise this problem.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

![]() Table 6.7

Table 6.7

Question

Relevance

Tooth brushing technique

Overzealous tooth brushing can lead to bleeding gums and gum recession. Make sure the patient is not ‘over cleaning’ their teeth. An electric tooth brush might be helpful for people who apply too much force when brushing teeth

Bleeding gums

Gums that bleed without exposure to trauma and is unexplained or unprovoked need referral to exclude underlying pathology

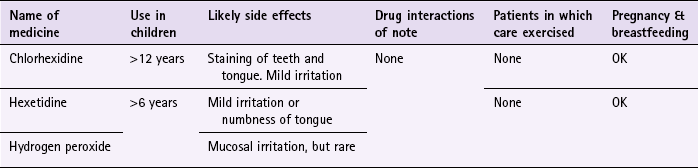

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

Hexetidine (Oraldene)

References

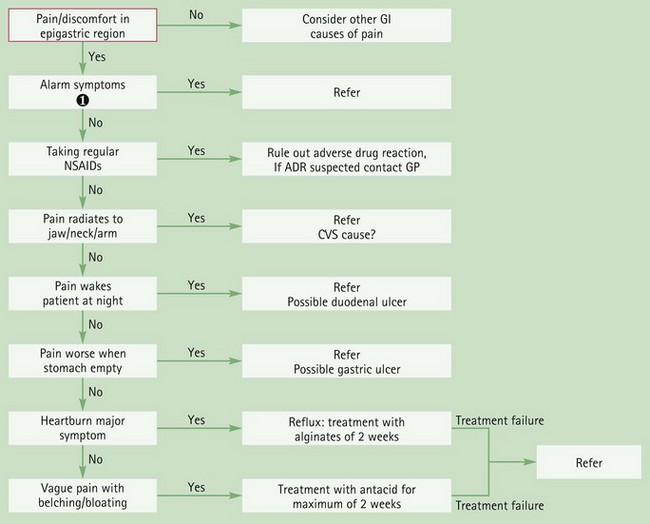

Background

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Non-ulcer dyspepsia

Unlikely

Medicine induced, peptic ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome

Very unlikely

Gastric and oesophageal cancers, atypical angina

![]() Table 6.10

Table 6.10

Question

Relevance

Age

The incidence of dyspepsia decreases with advancing age and therefore young adults are likely to suffer from dyspepsia with no specific pathologic condition, unlike patients over 50 years of age, in which a specific pathologic condition becomes more common

Location

Dyspepsia is experienced as pain above the umbilicus and centrally located (epigastric area). Pain below the umbilicus will not be due to dyspepsia

Pain experienced behind the sternum (breastbone) is likely to be heartburn

If the patient can point to a specific area of the abdomen then it is unlikely to be dyspepsia

Nature of pain

Pain associated with dyspepsia is described as aching or discomfort. Pain described as gnawing, sharp or stabbing is unlikely to be dyspepsia

Radiation

Pain that radiates to other areas of the body is indicative of more serious pathology and the patient must be referred. The pain might be cardiovascular in origin, especially if the pain is felt down the inside aspect of the left arm

Severity

Pain described as debilitating or severe must be referred to exclude more serious conditions

Associated symptoms

Persistent vomiting with or without blood is suggestive of ulceration or even cancer and must be referred

Black and tarry stools indicate a bleed in the GI tract and must be referred

Aggravating or relieving factors

Pain shortly after eating (1 to 3 hours) and relieved by food or antacids are classic symptoms of ulcers

Symptoms of dyspepsia are often brought on by certain types of food, for example caffeine containing products and spicy food

Social history

Bouts of excessive drinking are commonly implicated in dyspepsia. Likewise, eating food on the move or too quickly is often the cause of the symptoms. A person’s job is often a good clue to whether these are contributing to their symptoms

Clinical features of dyspepsia

Conditions to eliminate

Very unlikely causes

![]() Alarm symptoms

Alarm symptoms

These include, anaemia (signs can include tiredness and pale complexion), loss of weight, anorexia, dark stools, difficulty in swallowing, vomiting blood.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Proton pump inhibitors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastroenterology