EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect an abnormal gag reflex, immediately stop the patient’s oral intake to prevent aspiration. Quickly evaluate his level of consciousness (LOC). If it’s decreased, place him in a sidelying position to prevent aspiration; if not, place him in Fowler’s position. Have suction equipment at hand.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member if the patient can’t communicate) about the onset and duration of swallowing difficulties, if any. Are liquids more difficult to swallow than solids? Is swallowing more difficult at certain times of the day (as occurs in the bulbar palsy associated with myasthenia gravis)? If the patient also has trouble chewing, suspect more widespread neurologic involvement because chewing involves different CNs.

Explore the patient’s medical history for vascular and degenerative disorders. Then, assess his respiratory status for evidence of aspiration and perform a neurologic examination.

Medical Causes

- Basilar artery occlusion. Basilar artery occlusion may suddenly diminish or obliterate the gag reflex. It also causes diffuse sensory loss, dysarthria, facial weakness, extraocular muscle palsies, quadriplegia, and a decreased LOC.

- Brain stem glioma. Brain stem glioma causes a gradual loss of the gag reflex. Related symptoms reflect bilateral brain stem involvement and include diplopia and facial weakness. Common involvement of the corticospinal pathways causes spasticity and paresis of the arms and legs as well as gait disturbances.

- Bulbar palsy. Loss of the gag reflex reflects temporary or permanent paralysis of muscles supplied by CNs IX and X. Other indicators of bulbar palsy include jaw and facial muscle weakness, dysphagia, loss of sensation at the base of the tongue, increased salivation, possible difficulty articulating and breathing, and fasciculations.

- Wallenberg’s syndrome. In Wallenberg’s syndrome, the pharyngeal phase of swallowing and the gag reflex can become impaired. Symptoms usually have an acute onset, occurring within hours to days. The patient may experience loss of pain and temperature sensation ipsilaterally in the orofacial region and contralaterally on the body. Some patients lose their sense of taste on one side of the tongue, while maintaining taste sensations on the other side. Other patients may complain of uncontrollable hiccups, vomiting, rapid involuntary movements of the eyes (nystagmus), problems with balance and gait coordination, ipsilateral ataxia of the arm and leg, and signs of Horner’s syndrome (unilateral ptosis and miosis, hemifacial anhidrosis).

Other Causes

- Anesthesia. General and local (throat) anesthesia can produce temporary loss of the gag reflex.

Special Considerations

Continually assess the patient’s ability to swallow. If his gag reflex is absent, provide tube feedings; if it’s merely diminished, try pureed foods. Advise the patient to take small amounts and eat slowly while sitting or in high Fowler’s position. Stay with him while he eats and observe for choking. Remember to keep suction equipment handy in case of aspiration. Keep accurate intake and output records, and assess the patient’s nutritional status daily.

Refer the patient to a therapist to determine his aspiration risk and develop an exercise program to strengthen specific muscles.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as swallow studies, a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, EEG, lumbar puncture, and arteriography.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient to eat small amounts slowly while sitting or in high Fowler’s position. Teach him techniques for safe swallowing. Discuss the types and textures of foods that reduce the risk of choking.

Pediatric Pointers

Brain stem glioma is an important cause of an abnormal gag reflex in children.

REFERENCES

Murthy, J. (2010). Neurological complications of dengue infection. Neurology India, 58, 581–584.

Rodenhuis-Zybert, I. A., Wilschut, J., & Smit, J. M. (2010). Dengue virus life cycle: Viral and host factors modulating infectivity. Cellular and Molecular Life Science, 67, 2773–2786.

Gait, Bizarre

[Hysterical gait]

A bizarre gait has no obvious organic basis; rather, it’s produced unconsciously by a person with a somatoform disorder (hysterical neurosis) or consciously by a malingerer. The gait has no consistent pattern. It may mimic an organic impairment, but characteristically has a more theatrical or bizarre quality with key elements missing, such as a spastic gait without hip circumduction, or leg “paralysis” with normal reflexes and motor strength. Its manifestations may include wild gyrations, exaggerated stepping, leg dragging, or mimicking unusual walks such as that of a tightrope walker.

History and Physical Examination

If you suspect that the patient’s gait impairment has no organic cause, begin to investigate other possibilities. Ask the patient when he first developed the impairment and whether it coincided with a stressful period or event, such as the death of a loved one or loss of a job. Ask about associated symptoms, and explore reports of frequent unexplained illnesses and multiple physician’s visits. Subtly try to determine if the patient will gain anything from malingering, for instance, added attention or an insurance settlement.

Begin the physical examination by testing the patient’s reflexes and sensorimotor function, noting abnormal response patterns. To quickly check his reports of leg weakness or paralysis, perform a test for Hoover’s sign: Place the patient in the supine position and stand at his feet. Cradle a heel in each of your palms and rest your hands on the table. Ask the patient to raise the affected leg. In true motor weakness, the heel of the other leg will press downward; in hysteria, this movement will be absent. As a further check, observe the patient for normal movements when he’s unaware of being watched.

Medical Causes

- Conversion disorder. Conversion disorder is a rare somatoform disorder, in which a bizarre gait or paralysis may develop after severe stress and isn’t accompanied by other symptoms. The patient typically shows indifference toward his impairment.

- Malingering. Malingering is a rare cause of bizarre gait, in which the patient may also complain of a headache and chest and back pain.

- Somatization disorder. Bizarre gait is one of many possible somatic complaints. The patient may exhibit any combination of pseudoneurologic signs and symptoms — fainting, weakness, memory loss, dysphagia, visual problems (diplopia, vision loss, blurred vision), loss of voice, seizures, and bladder dysfunction. He may also report pain in the back, joints, and extremities (most commonly the legs) and complaints in almost any body system. For example, characteristic GI complaints include pain, bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

The patient’s reflexes and motor strength remain normal, but peculiar contractures and arm or leg rigidity may occur. His reputed sensory loss doesn’t conform to a known sensory dermatome. In some cases, he won’t stand or walk (astasia/abasia), remaining bedridden although still able to move his legs in bed.

Special Considerations

A full neurologic workup may be necessary to completely rule out an organic cause of the patient’s abnormal gait. Remember, even though bizarre gait has no organic basis, it’s real to the patient (unless, of course, he’s malingering). Avoid expressing judgment on the patient’s actions or motives; you’ll need to be supportive and reinforce positive progress. Because muscle atrophy and bone demineralization can develop in a bedridden patient, encourage ambulation and resumption of normal activities. Consider a referral for psychiatric counseling as appropriate.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in the use of assistive devices, as necessary. Review safety measures such as wearing proper footwear.

Pediatric Pointers

Bizarre gait is rare in patients younger than age 8. More common in prepubescence, it usually results from conversion disorder.

REFERENCES

Debi, R., Mor, A., Segal, G., Segal, O., Agar, G., Debbi, E., … Elbaz A. (2011). Correlation between single limb support phase and self-evaluation questionnaires in knee osteoarthritis populations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33, 1103–1109.

Elbaz, A., Mor, A., Segal, O., Agar, G., Halperin, N., Haim, A., … Debi, R. (2012). Can single limb support objectively assess the functional severity of knee osteoarthritis? Knee, 12(1), 32–35.

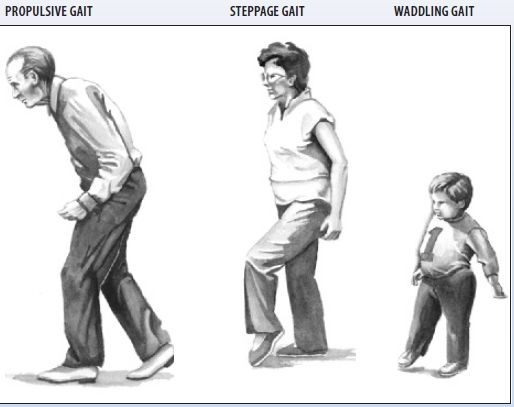

Gait, Propulsive

[Festinating gait]

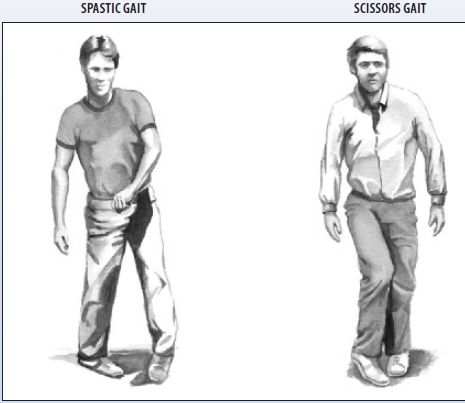

Propulsive gait is characterized by a stooped, rigid posture — the patient’s head and neck are bent forward; his flexed, stiffened arms are held away from the body; his fingers are extended; and his knees and hips are stiffly bent. During ambulation, this posture results in a forward shifting of the body’s center of gravity and consequent impairment of balance, causing increasingly rapid, short, shuffling steps with involuntary acceleration (festination) and lack of control over forward motion (propulsion) or backward motion (retropulsion). (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities.)

Identifying Gait Abnormalities

Propulsive gait is a cardinal sign of advanced Parkinson’s disease; it results from progressive degeneration of the ganglia, which are primarily responsible for smooth muscle movement. Because this sign develops gradually and its accompanying effects are usually wrongly attributed to aging, propulsive gait commonly goes unnoticed or unreported until severe disability results.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when his gait impairment first developed and whether it has recently worsened. Because he may have difficulty remembering, having attributed the gait to “old age” or disease processes, you may be able to gain information from family members or friends, especially those who see the patient only sporadically.

Also, obtain a thorough drug history, including medication type and dosage. Ask the patient if he has been taking tranquilizers, especially phenothiazines. If he knows he has Parkinson’s disease and has been taking levodopa, pay particular attention to the dosage because an overdose can cause an acute exacerbation of signs and symptoms. If Parkinson’s disease isn’t a known or suspected diagnosis, ask the patient if he has been acutely or routinely exposed to carbon monoxide or manganese.

Begin the physical examination by testing the patient’s reflexes and sensorimotor function, noting abnormal response patterns.

Medical Causes

- Parkinson’s disease. The characteristic and permanent propulsive gait begins early as a shuffle. As the disease progresses, the gait slows. Cardinal signs of the disease are progressive muscle rigidity, which may be uniform (lead-pipe rigidity) or jerky (cogwheel rigidity); akinesia; and an insidious tremor that begins in the fingers, increases during stress or anxiety, and decreases with purposeful movement and sleep. Besides the gait, akinesia also typically produces a monotone voice, drooling, masklike facies, a stooped posture, and dysarthria, dysphagia, or both. Occasionally, it also causes oculogyric crises or blepharospasm.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Propulsive gait and possibly other extrapyramidal effects can result from the use of phenothiazines, other antipsychotics (notably haloperidol, thiothixene, and loxapine) and, infrequently, metoclopramide and metyrosine. Such effects are usually temporary, disappearing within a few weeks after therapy is discontinued.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning. A propulsive gait commonly appears several weeks after acute carbon monoxide intoxication. Earlier effects include muscle rigidity, choreoathetoid movements, generalized seizures, myoclonic jerks, masklike facies, and dementia.

- Manganese poisoning. Chronic overexposure to manganese can cause an insidious, usually permanent, propulsive gait. Typical early findings include fatigue, muscle weakness and rigidity, dystonia, resting tremor, choreoathetoid movements, masklike facies, and personality changes. Those at risk for manganese poisoning are welders, railroad workers, miners, steelworkers, and workers who handle pesticides.

Special Considerations

Because of his gait and associated motor impairment, the patient may have problems performing activities of daily living. Assist him as appropriate, while at the same time encouraging his independence, self-reliance, and confidence. Advise the patient and his family to allow plenty of time for these activities, especially walking, because he’s particularly susceptible to falls due to festination and poor balance. Encourage the patient to maintain ambulation; for safety reasons, remember to stay with him while he’s walking, especially if he’s on unfamiliar or uneven ground. You may need to refer him to a physical therapist for exercise therapy and gait retraining.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient and his family to allow plenty of time for walking to avoid falls. Instruct the patient on the use of assistive devices, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

Propulsive gait, usually with severe tremors, typically occurs in juvenile parkinsonism, a rare form. Other possible but rare causes include Hallervorden-Spatz disease and kernicterus.

REFERENCES

Dean, C. M., Ada, L., Bampton, J., Morris, M. E., Katrak P. H., & Potts, S. (2010). Treadmill walking with body weight support in sub acute non-ambulatory stroke improves walking capacity more than overground walking: A randomised trial. Journal of Geophysics Research, 56(2), 97–103.

Yen, S. C., Schmit, B. D., Landry, J. M., Roth, H., & Wu, M. (2012). Locomotor adaptation to resistance during treadmill training transfers to overground walking in human. Experimental Brain Research, 216(3), 473–482.

Gait, Scissors

Resulting from bilateral spastic paresis (diplegia), scissors gait affects both legs and has little or no effect on the arms. The patient’s legs flex slightly at the hips and knees, so he looks as if he’s crouching. With each step, his thighs adduct and his knees hit or cross in a scissors-like movement. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) His steps are short, regular, and laborious, as if he were wading through waist-deep water. His feet may be plantar flexed and turned inward, with a shortened Achilles tendon; as a result, he walks on his toes or on the balls of his feet and may scrape his toes on the ground.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member, if the patient can’t answer) about the onset and duration of the gait. Has it progressively worsened or remained constant? Ask about a history of trauma, including birth trauma, and neurologic disorders. Thoroughly evaluate motor and sensory function and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the legs.

Medical Causes

- Cerebral palsy. In the spastic form of cerebral palsy, patients walk on their toes with a scissors gait. Other features include hyperactive DTRs, increased stretch reflexes, rapid alternating muscle contraction and relaxation, muscle weakness, underdevelopment of affected limbs, and a tendency toward contractures.

- Cervical spondylosis with myelopathy. Scissors gait develops in the late stages of cervical spondylosis with myelopathy and steadily worsens. Related findings mimic those of a herniated disk: severe low back pain, which may radiate to the buttocks, legs, and feet; muscle spasms; sensorimotor loss; and muscle weakness and atrophy.

- Multiple sclerosis. Progressive scissors gait usually develops gradually, with infrequent remissions. Characteristic muscle weakness, usually in the legs, ranges from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Related findings include facial pain, vision disturbances, paresthesia, incoordination, and loss of proprioception and vibration sensation in the ankle and toes.

- Spinal cord tumor. Scissors gait can develop gradually from a thoracic or lumbar tumor. Other findings reflect the location of the tumor and may include radicular, subscapular, shoulder, groin, leg, or flank pain; muscle spasms or fasciculations; muscle atrophy; sensory deficits, such as paresthesia and a girdle sensation of the abdomen and chest; hyperactive DTRs; a bilateral Babinski’s reflex; spastic neurogenic bladder; and sexual dysfunction.

- Syringomyelia. Scissors gait usually occurs late in syringomyelia, along with analgesia and thermanesthesia, muscle atrophy and weakness, and Charcot’s joints. Other effects may include the loss of fingernails, fingers, or toes; Dupuytren’s contracture of the palms; scoliosis; and clubfoot. Skin in the affected areas is commonly dry, scaly, and grooved.

Special Considerations

Because of the sensory loss associated with scissors gait, provide meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown and pressure ulcer formation. Also, give the patient and his family complete skin care instructions. If appropriate, provide bladder and bowel retraining.

Provide daily active and passive range-of-motion exercises. Referral to a physical therapist may be required for gait retraining and for possible in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain proper foot alignment for standing and walking.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient and his family on complete skin care. Teach them about bladder and bowel retraining, if appropriate. Reinforce the proper use of splints or braces, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

The major causes of scissors gait in children are cerebral palsy, hereditary spastic paraplegia, and spinal injury at birth. If spastic paraplegia is present at birth, scissors gait becomes apparent when the child begins to walk, which is usually later than normal.

REFERENCES

Callisaya, M. L., Blizzard, L., Schmidt, M. D., McGinley, J. L., & Srikanth, V. K. (2010). Ageing and gait variability—a population-based study of older people. Age Ageing, 39(2), 191–197.

De Laat, K. F., van Norden, A. G., Gons, R. A., van Oudheusden, L. J., van Uden, I. W., Bloem, B. R., … de Leeuw, F. E. (2010). Gait in elderly with cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke, 41(8), 1652–1658.

Gait, Spastic

[Hemiplegic gait]

Spastic gait — sometimes referred to as paretic or weak gait—is a stiff, foot-dragging walk caused by unilateral leg muscle hypertonicity. This gait indicates focal damage to the corticospinal tract. The affected leg becomes rigid, with a marked decrease in flexion at the hip and knee and possibly plantar flexion and equinovarus deformity of the foot. Because the patient’s leg doesn’t swing normally at the hip or knee, his foot tends to drag or shuffle, scraping his toes on the ground. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) To compensate, the pelvis of the affected side tilts upward in an attempt to lift the toes, causing the patient’s leg to abduct and circumduct. Also, arm swing is hindered on the same side as the affected leg.

Spastic gait usually develops after a period of flaccidity (hypotonicity) in the affected leg. Whatever the cause, the gait is usually permanent after it develops.

History and Physical Examination

Find out when the patient first noticed the gait impairment and whether it developed suddenly or gradually. Ask him if it waxes and wanes, or if it has worsened progressively. Does fatigue, hot weather, or warm baths or showers worsen the gait? Such exacerbation typically occurs in multiple sclerosis. Focus your medical history questions on neurologic disorders, recent head trauma, and degenerative diseases.

During the physical examination, test and compare strength, range of motion (ROM), and sensory function in all limbs. Also, observe and palpate for muscle flaccidity or atrophy.

Medical Causes

- Brain abscess. In brain abscess, spastic gait generally develops slowly after a period of muscle flaccidity and fever. Early signs and symptoms of abscess reflect increased intracranial pressure (ICP): a headache, nausea, vomiting, and focal or generalized seizures. Later, site-specific features may include hemiparesis, tremors, visual disturbances, nystagmus, and pupillary inequality. The patient’s level of consciousness may range from drowsiness to stupor.

- Brain tumor. Depending on the site and type of tumor, spastic gait usually develops gradually and worsens over time. Accompanying effects may include signs of increased ICP (a headache, nausea, vomiting, and focal or generalized seizures), papilledema, sensory loss on the affected side, dysarthria, ocular palsies, aphasia, and personality changes.

- Head trauma. Spastic gait typically follows the acute stage of head trauma. The patient may also experience focal or generalized seizures, personality changes, a headache, and focal neurologic signs, such as aphasia and visual field deficits.

- Multiple sclerosis. Spastic gait begins insidiously and follows multiple sclerosis’ characteristic cycle of remission and exacerbation. The gait, as well as other signs and symptoms, commonly worsens in warm weather or after a warm bath or shower. Characteristic weakness, usually affecting the legs, ranges from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Other effects include facial pain, paresthesia, incoordination, loss of proprioception and vibration sensation in the ankle and toes, and vision disturbances.

- Stroke. Spastic gait usually appears after a period of muscle weakness and hypotonicity on the affected side. Associated effects may include unilateral muscle atrophy, sensory loss, and footdrop; aphasia; dysarthria; dysphagia; visual field deficits; diplopia; and ocular palsies.

Special Considerations

Because leg muscle contractures are commonly associated with spastic gait, promote daily exercise and active and passive ROM exercises. The patient may have poor balance and a tendency to fall to the paralyzed side, so stay with him while he’s walking. Provide a cane or a walker, as indicated. As appropriate, refer the patient to a physical therapist for gait retraining and possible in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain proper foot alignment for standing and walking.

Patient Counseling

Reinforce the importance of ambulating with assistance. Teach the patient to use a cane or a walker, as indicated.

Pediatric Pointers

Causes of spastic gait in children include sickle cell crisis, cerebral palsy, porencephalic cysts, and arteriovenous malformation that causes hemorrhage or ischemia.

REFERENCES

Ahmari, S. E., Spellman, T., Douglass, N. L., Kheirbek, M. A., Simpson, H. B., Deisseroth, K., … Hen, R. (2013). Repeated cortico-striatal stimulation generates persistent OCD-like behavior. Science, 340, 1234–1239.

Air, E. L., Ostrem, J. L., Sanger, T. D., & Starr, P. A. (2011). Deep brain stimulation in children: Experience and technical pearls. Journal of Neurosurgical Pediatrics, 8, 566–574.

Gait, Steppage

[Equine gait, paretic gait, prancing gait, weak gait]

Steppage gait typically results from footdrop caused by weakness or paralysis of pretibial and peroneal muscles, usually from lower motor neuron lesions. Footdrop causes the foot to hang with the toes pointing down, causing the toes to scrape the ground during ambulation. To compensate, the hip rotates outward and the hip and knee flex in an exaggerated fashion to lift the advancing leg off the ground. The foot is thrown forward, and the toes hit the ground first, producing an audible slap. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) The rhythm of the gait is usually regular, with even steps and normal upper body posture and arm swing. Steppage gait can be unilateral or bilateral and permanent or transient, depending on the site and type of neural damage.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient about the onset of the gait and recent changes in its character. Does a family member have a similar gait? Find out if the patient has had a traumatic injury to the buttocks, hips, legs, or knees. Ask about a history of chronic disorders that may be associated with polyneuropathy, such as diabetes mellitus, polyarteritis nodosa, and alcoholism. While you’re taking the history, observe whether the patient crosses his legs while sitting because this may put pressure on the peroneal nerve.

Inspect and palpate the patient’s calves and feet for muscle atrophy and wasting. Using a pin, test for sensory deficits along the entire length of both legs.

Medical Causes

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. Typically occurring after recovery from the acute stage of Guillain-Barré syndrome, steppage gait can be mild or severe and unilateral or bilateral; it’s invariably permanent. Muscle weakness usually begins in the legs, extends to the arms and face within 72 hours, and can progress to total motor paralysis and respiratory failure. Other effects include footdrop, transient paresthesia, hypernasality, dysphagia, diaphoresis, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and incontinence.

- Herniated lumbar disk. Unilateral steppage gait and footdrop commonly occur with late-stage weakness and atrophy of leg muscles. However, the most pronounced symptom is severe low back pain, which may radiate to the buttocks, legs, and feet, usually unilaterally. Sciatic pain follows, often accompanied by muscle spasms and sensorimotor loss. Paresthesia and fasciculations may occur.

- Multiple sclerosis. Steppage gait and footdrop typically fluctuate in severity with multiple sclerosis’ characteristic cycle of periodic exacerbation and remission. Muscle weakness, usually affecting the legs, can range from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Related findings include facial pain, visual disturbances, paresthesia, incoordination, and sensory loss in the ankle and toes.

- Peroneal muscle atrophy. Bilateral steppage gait and footdrop begin insidiously in peroneal muscle atrophy. Foot, peroneal, and ankle dorsiflexor muscles are affected first. Other early signs and symptoms include paresthesia, aching, and cramping in the feet and legs along with coldness, swelling, and cyanosis. As the disorder progresses, all leg muscles become weak and atrophic, with hypoactive or absent deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). Later, atrophy and sensory losses spread to the hands and arms.

- Peroneal nerve trauma. Temporary ipsilateral steppage gait occurs suddenly but resolves with the release of peroneal nerve pressure. The gait is associated with footdrop and muscle weakness and sensory loss over the lateral surface of the calf and foot.

Special Considerations

The patient with steppage gait may tire rapidly when walking because of the extra effort he must expend to lift his feet off the ground. When he tires, he may stub his toes, causing a fall. To prevent this, help the patient recognize his exercise limits and encourage him to get adequate rest. Refer him to a physical therapist, if appropriate, for gait retraining and possible application of in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain correct foot alignment.

Patient Counseling

Help the patient to recognize his exercise limits and encourage him to get adequate rest. Teach the patient how to use splints and braces.

REFERENCES

Kallmes, D. F., Comstock, B. A., Heagerty, P. J., Turner, J. A., Wilson, D. J., Diamond, T. H., … Jarvik J. G. (2009). A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 569–579.

Kumar, G., Goyal, M. K., Lucchese, S., & Dhand, U. (2011). Copper deficiency myelopathy can also involve the brain stem. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 32, 14–15.

Gait, Waddling

Waddling gait, a distinctive ducklike walk, is an important sign of muscular dystrophy, spinal muscle atrophy or, rarely, congenital hip displacement. It may be present when the child begins to walk or may appear only later in life. The gait results from deterioration of the pelvic girdle muscles — primarily the gluteus medius, hip flexors, and hip extensors. Weakness in these muscles hinders stabilization of the weight-bearing hip during walking, causing the opposite hip to drop and the trunk to lean toward that side in an attempt to maintain balance. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.)

Typically, the legs assume a wide stance, and the trunk is thrown back to further improve stability, exaggerating lordosis, and abdominal protrusion. In severe cases, leg and foot muscle contractures may cause equinovarus deformity of the foot combined with circumduction or bowing of the legs.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member, if the patient is a young child) when the gait first appeared and if it has recently worsened. To determine the extent of pelvic girdle and leg muscle weakness, ask if the patient falls frequently or has difficulty climbing stairs, rising from a chair, or walking. Also, find out if he was late in learning to walk or holding his head upright. Obtain a family history, focusing on problems of muscle weakness and gait and on congenital motor disorders.

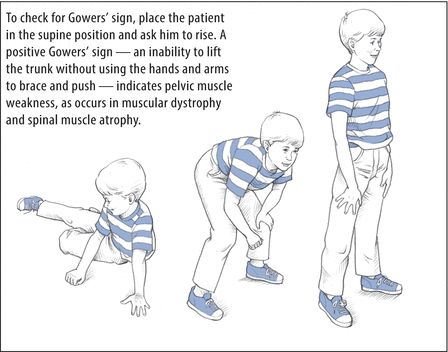

Inspect and palpate leg muscles, especially the calves, for size and tone. Check for a positive Gowers’ sign, which indicates pelvic muscle weakness. (See Identifying Gowers’ Sign.) Next, assess motor strength and function in the shoulders, arms, and hands, looking for weakness or asymmetrical movements.

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Gowers’ Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Gowers’ Sign

To check for Gowers’ sign, place the patient in the supine position and ask him to rise. A positive Gowers’ sign — an inability to lift the trunk without using the hands and arms to brace and push — indicates pelvic muscle weakness, as occurs in muscular dystrophy and spinal muscle atrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree