Food-Based Dietary Guidelines For Healthier Populations: International Considerations1

Ricardo Uauy

Sophie Hawkesworth

Alan D. Dangour

1Abbreviations: Apo-E, apolipoprotein-E; DRI, dietary reference intake; EAR, estimated average requirement; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization; FBDG, food-based dietary guideline; IDD, iodine deficiency disorders; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; RNI, recommended nutrient intake; RUTF, ready-to-use therapeutic food; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; WHO, World Health Organization.

The modern approach toward defining the nutritional adequacy of diets has progressed over the past two centuries in parallel with scientific understanding of the biochemical and physiologic basis of human nutritional requirements in health and disease. The definition of essential nutrients and nutrient requirements has provided the scientific underpinnings for nutrient-based dietary recommendations, which now exist for virtually every essential nutrient known (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). However, obvious limitations exist to the reductionist nutrient-based approach because people consume foods and not nutrients. Moreover, the effect of specific foods and of dietary patterns on health goes well beyond the combination of essential nutrients the food may contain.

Given our present understanding of food-health relationships, it seems likely that a large variety of foods can be combined in varying amounts to provide a healthy diet. Thus, it is difficult to determine a precise indispensable intake of individual foods that can, when combined with other foods, provide a nutritionally adequate diet under all conditions. The prevailing view is that a large set of food combinations are compatible with nutritional adequacy, but that no given set of foods can be extrapolated as absolutely required or sufficient across different ecologic settings. Trends in the globalization of food supply provide clear evidence that dietary patterns and even traditionally local foods can move across geographic niches.

Recommended nutrient intakes (RNIs) are customarily defined as the intake of energy and specific nutrients necessary to satisfy the requirements of a group of healthy individuals. These are discussed further in the chapter on dietary reference intakes (DRIs). This nutrient-based approach has served well to advance science but has not always fostered the establishment of nutritional and dietary priorities consistent with broad public health interests at national and international levels. For example, the emphasis on protein quality of single food sources placed a premium on the development of animal foods and failed to include amino acid complementarities, which increase the quality of mixed vegetable protein sources. We now know that human protein needs can also be met with predominantly plant-based protein sources. In contrast to this nutrient-based approach, food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs) address health concerns related to dietary insufficiency, excess, or imbalance with a broader perspective, considering the totality of the effects of a given dietary pattern (7). They are more closely linked to the diet-health relationships of relevance to the particular country or region of interest (8). In addition, they take into account the customary dietary pattern, the foods available, and the factors that determine the consumption of foods. They consider the ecologic setting, the socioeconomic and cultural factors, and the biologic and physical environment that affects the health and nutrition of a given population or community. Finally, they are easy to understand and accessible for all members of a population.

BASIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DEFINING FOOD-BASED DIETARY GUIDELINES

The Joint Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (8) has indicated the need to consider the following nine key factors in developing national FBDGs:

Scientific evidence concerning diet-health relationships

The prevalence of diet-related public health problems

Food consumption patterns of the population

Nutritional requirements

The potential food supply

The composition of foods, including consideration of food preparation practices

The bioavailability of nutrients supplied by the mixed local diet

Sociocultural factors that relate to food choices and accessibility

Food costs

In the following section, we discuss some of these in greater detail, including the need for an understanding of the nutritional requirements of the population under question, of their nutrition-related health concerns that require addressing, and their habitual nutritional intake, informed by an understanding of food composition and availability.

Nutritional Requirements

A clear definition of the nutritional requirements of the population is a key priority embodied in the FBDGs for improved nutrition, health, and well-being. In this setting, Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNIs) are used as basic criteria against which the sufficiency of the current and proposed diets can be assessed. RNIs can also be used to support educational efforts in the implementation of dietary guidelines and to provide a basis for consumer information on the nutritional adequacy of specific foods.

The criteria used to estimate nutritional requirements have changed over time as described elsewhere in this text. The main approaches used in establishing international recommendations are listed here:

The clinical approach is based on the need to correct or prevent nutrient-specific diseases associated with intake deficiency. (Signs and symptoms of nutritional deficit and/or excess are provided in the nutrient specific chapters of this book). This methodology is highly specific but for ethical reasons is clearly an inappropriate method for establishing nutrient dose-responses. However, information sporadically gathered from unintended outbreaks of deficit or excess can be used to define the levels of intake at which clinical signs or symptoms appear.

Functional indicators of nutritional sufficiency (molecular, cellular, biochemical, physiologic) can be used to assess nutritional normalcy and to define the limits for deficit and excess of specific nutrients. This approach is based on a defined set of biomarkers that are sensitive to changes in nutritional state and are specific for identifying subclinical deficiency conditions. The set of biomarkers that can be used to define requirements include measures of nutrient stores, nutrient turnover, or critical tissue/organ pools. The use of balance data to define requirements should be avoided whenever possible because adaptation to intake may lead to equilibrium at a fairly wide range of intakes (8). The same applies to nutrient blood levels because they usually reflect levels of intake and absorption rather than functional state.

The habitual consumption levels of “healthy” populations serve as a basis to establish a range of adequate intakes. In the absence of quantitative estimates based on the clinical or functional indicators of sufficiency, this criterion remains the first approximation to establishing requirements.

More recently the concept of optimal nutrient intake has emerged, influencing both scientists and the public alike. The idea of optimal nutrient intake is based on the quest for improved functionality, be it in terms of muscle strength, immune function, or intellectual ability. The question “optimal for what?” is usually answered by the suggestion that diet or specific nutrients can improve or enhance a given function, ameliorate age-related decline in function, or decrease the burden of illness associated with loss of function. The goal is to add healthy life years and prevent disability; this is in line with the use of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) as a measure of health. However, the concept of optimal intake is too broad to be assessed quantitatively and usually unsupported by appropriate population-based controlled studies. Thus, the preferred approach is to clearly define the goal that is of public health interest in relation to the intake of a specific nutrient or a given food. The selected goal should be directly related to a function of relevance to health or quality of life.

The quantified RNI estimates derived from these various approaches may differ for any given nutrient, although the implications of these differences in the establishment of FBDGs are usually small (9, 10). Other chapters of this book illustrate the various approaches in establishing RNIs and provide the basis and numeric estimates used by various national and international expert groups. RNIs serve as the basis to establish nutrient intake goals, which correspond to the desired target intakes that will achieve better health and nutrition for a given population within an ecologic setting. Their purpose is to promote overall health and/or control specific nutritional disease induced by excess or deficit and to reduce health risks considering

the multifactorial nature of disease. Once nutrient intake goals are defined, FBDGs can be established, taking into account the customary dietary pattern, the foods available, and the factors that determine the consumption of foods, indicating which aspects should be modified.

the multifactorial nature of disease. Once nutrient intake goals are defined, FBDGs can be established, taking into account the customary dietary pattern, the foods available, and the factors that determine the consumption of foods, indicating which aspects should be modified.

Nutrient Content of Foods and Bioavailability

Accurate information on the chemical composition of foods is needed to assess diets, prevent and control micronutrient deficiencies, provide accurate information to consumers using nutrition labels, and promote healthy diets. Unfortunately, food composition data for many regions of the world are insufficient or inadequate, thus limiting the assessment of dietary quality and the effectiveness of proposed interventions. The demand for data on the nutrient composition of foods to generate FBDGs serves to advocate for more complete and updated information on food composition worldwide. Stimulating an interest in food composition among government, industry, and consumer interest groups will be crucial for this process to occur.

The recognition of various situations where deficiency occurs in the presence of adequate micronutrient content in the food supply has elicited great interest in determining the proportion of nutrients in food that is available for utilization by the body (bioavailability). The state of the art methodologies to evaluate bioavailability of micronutrients are provided in detail in different chapters of this book. We will highlight here some aspects of particular relevance in defining optimal food combinations when establishing FBDGs.

Both food preparation and dietary practices need to be considered when attempting to attain vitamin A, vitamin C, folate, iron, and zinc dietary adequacy using food-based approaches. For example it is important to recommend that vegetables rich in vitamin C, folate, and other water-soluble or heat-liable vitamins be cooked or steamed in small amounts of water over short periods of time. In the case of iron bioavailability, it is essential to reduce the intake of inhibitors of absorption and to increase the intake of enhancers in a given meal. Following this strategy, it is recommended to increase the intake of germinated seeds, fermented cereals and/ or heat processed cereals, meats, and fruits or vegetables rich in vitamin C. At the same time, guidelines should recommend a decrease in the intake of high-fiber foods and high-polyphenol foods such as tea, coffee, chocolate, and herbal teas and to separate their intake from iron rich meals (11). In the case of zinc, flesh foods improve zinc absorption, whereas diets high in phytate, particularly unrefined cereal-based diets, inhibit zinc absorption. Zinc availability can be estimated according to the phytate/zinc (molar) ratio of the meal (12).

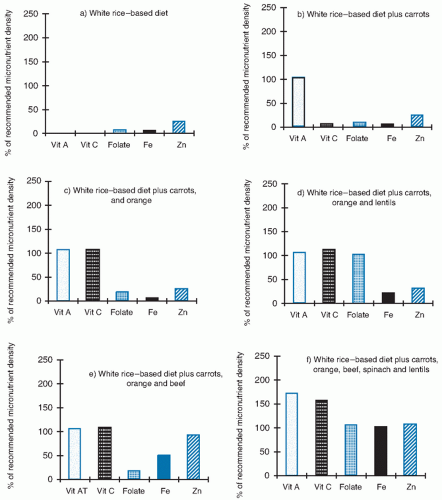

Major cereal/tuber-based diets are clearly insufficient in vitamin A, vitamin C, folate, iron, and zinc in terms of both content and bioavailability. Although the inclusion of a few micronutrient-rich foods can be successfully used to achieve dietary adequacy, the optimal levels of folate, iron, and zinc commonly require a small amount of animal flesh as a source of micronutrients. This addition will improve nutrient density and also the bioavailability of iron present in plant sources. A careful combination of plant foods, including legumes, fermented foods, sprouting seeds, and single cell extracts such as brewer’s yeast can also provide the required critical micronutrients for groups that opt to limit or exclude animal foods from their diet.

Figure 110.1 illustrates how food combinations serve to complement specific staple foods by providing a balance of specific nutrients. The figure presents information on key micronutrients and presents dietary adequacy in terms of recommended nutrient density. It is clear that rice alone, consumed in amounts that satisfy energy needs, is insufficient to meet micronutrient requirements. However, in combination with five or six small portions (˜50 g) of other foods, this diet can provide the necessary nutrient density to meet recommended nutrient intakes.

Nutritional Adequacy of Population Dietary Intakes

A healthy diet can be attained in multiple ways, given the variety of foods that can be combined. In practice, the set of food combinations that are compatible with nutritional adequacy is restricted by the level of food production that is sustainable in a given ecologic and population setting. In most countries this restriction has been overcome because imported food can provide for a stable food supply independent of local food production. Of greater significance are the economic constraints that limit food supply at the household level; these frequently are the true underlying cause of nutritional deficiencies. The development of FBDGs recognizes this inherent variability and focuses on the food combinations that can best meet nutrient requirements, rather than on how best to ensure that each specific nutrient is provided in adequate amounts.

The use of dietary recommendations in assessing the adequacy of nutrient intakes of populations requires good quantitative information of the distribution of usual nutrient intakes as well as knowledge of the distribution of requirements. The assessment of intake should include all sources of nutrient intake: food, water, and supplements. As discussed previously, appropriate dietary and food composition data are essential to achieve a valid estimate of intakes. The day-to-day variation in individual intakes can be minimized by collecting intake data over several days. Direct estimates of individual food consumption for a population are generally derived from surveys conducted on nationally representative samples. When conducted properly, individual dietary intake data from population surveys can often be subdivided by age and sex categories and used to investigate regional and socioeconomic variations. However, there is a surprising paucity of nationally representative surveys even from high-income country settings, in part because of the complexities and expense involved in conducting regular high-quality rounds of data collection and analysis (13).

Fig. 110.1. Example of food-based dietary diversification to meet micronutrient needs. A white rice-based diet has been enriched with small amounts of micronutrient rich foods; vitamin A, vitamin C, folate, iron, and zinc adequacy expressed as percentage of recommended nutrient density values proposed in reference 8. Details of nutrient content and amount of food in the combinations are available elsewhere (33). |

Household budget surveys (HBS) are conducted in many countries and provide information on food availability at a household level based on household expenditures. Because the household is the basic unit for food consumption under most settings, if there is enough food, individual members of the household can consume a diet within the recommended nutrient density values to meet the need for specific nutrients. However, this method does not address the issue of unequal intrahousehold food distribution, which may affect the intake of certain subgroups such as children, women, and older people who may not receive an equitable portion of foods with higher nutrient density (14). This should be taken into account in establishing both general dietary guidelines and those specifically addressing the needs of vulnerable groups in the community.

Several statistical approaches can be used to estimate the prevalence of inadequate intakes from the distribution of intakes and requirements. A simplified method is the estimated average requirement (EAR) cut-point approach, which defines the fraction of a population that consumes less than the EAR for a given nutrient. It assumes that the variability of individual intakes is at least as large as the variability in requirements and that the distribution of intakes and requirements are independent of each other. The latter is commonly the case for vitamins and minerals, but clearly it is not the case for energy intake. The EAR cut-point method requires a single population with a symmetrical distribution around the mean. If these conditions are met, the prevalence of inadequate intakes corresponds to the proportion of intakes that fall below the EAR. It is clearly inappropriate to examine mean values of population intakes and take the proportion that fall below the RNI to define the population at risk of inadequacy. The relevant information is the proportion of intakes in a population group that is below the EAR (8, 15). It is not absolutely necessary to define exact quantitative estimates of nutritional needs to assess the adequacy of FBDGs. Dietary quality can be assessed by comparing a given food combination with established recommendations.

Under certain physiologic conditions such as pregnancy or rapid growth during infancy, energy needs may not increase in direct proportion to the increased requirements for specific nutrients. In these situations, consumption of more of the same foods may not secure adequate protein, vitamin, or mineral intake to meet the recommended intakes. For these reasons, FBDGs usually exclude children less than 2 years of age as well as pregnant and lactating women. Specific guidelines for these groups have been established by some expert groups and international bodies (16, 17).

STEPS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FOOD-BASED DIETARY GUIDELINES

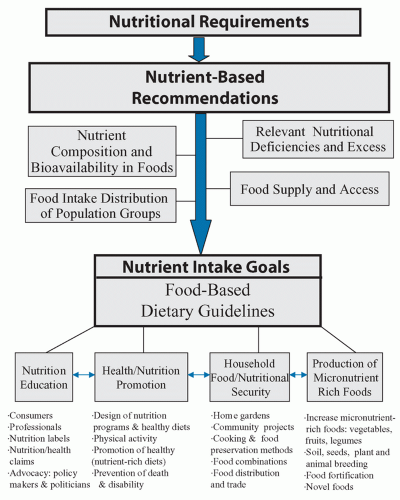

As we have shown, FBDGs are an instrument and an expression of food and nutrition policy based directly on diet and disease relationships of particular relevance to individual countries. Priorities in establishing dietary guidelines will thereby address the relevant public health concerns whether they are related to dietary insufficiency, excess, or a combination of the two. In this context, meeting the nutritional needs of the population is just one of the food and nutrition policy goals included in the FBDGs that are aimed at improving the health and nutrition of a given population. Dietary guidelines also serve to educate the public through the mass media and provide a practical guide in selecting foods by defining dietary adequacy. Advice for a healthy diet should provide both a quantitative and qualitative description of the diet to be understood by individuals, with information on both the size and number of servings per day. The FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines suggests following a systematic approach in developing FBDGs (8). This model, summarized in the following paragraphs and in Figure 110.2,

has been tested and used by various countries with necessary local adaptations to ensure better implementation.

has been tested and used by various countries with necessary local adaptations to ensure better implementation.

The initial step is the establishment of a working group that includes all relevant stakeholders. Membership should be broad, representing private and government institutions, agricultural and food industries, communication and anthropology specialists, nutrition scientists, consumer organizations, public health, and medical nutritionists. There should be thorough discussion of the relevant nutrition problems of the region of interest based on up-to-date survey information, ideally representing different regions and population groups. Information will be required on the prevailing nutrition-related disease issues of the population in question as well as on habitual diet patterns and food availability data. Once identified, the dietary component of the public health nutritional problem should be defined further. Dietary factors (nutrient excess, deficit or imbalance) should be examined beyond mean population intakes because there may be overconsumption or underconsumption in specific population groups. For example, there may be a shift in the overall population intake or a distinct subpopulation that does not consume the given nutrient. These problems should be addressed differently, in the first case increasing the nutrient intake for the complete population and in the latter case acting to increase the intake of the specific population subgroup of underconsumers. This can represent a practical problem, because in some cases it may be virtually impossible to identify such a subgroup and implementation strategies may be difficult to target at a particular group alone.

The working group should discuss and prioritize the set of major public nutrition problems that will be addressed by the FBDGs and explore the foods available to improve the nutritional problem. There may be a need to explore whether it is possible to change the pattern of agricultural production and food distribution. There also may be a need to modify food subsidies, apparent or hidden, or other government policies that affect food consumption. The economic constraints in implementing food-based approaches should be considered, as well as the possible solutions. This will clearly be different for urban societies who depend on an industrialized food supply, and selfsufficient farmers who consume what they produce.

The working group should then define a set of FBDGs that will address the nutrient intake/food patterns that require modification, considering the social, cultural, and economic factors that exist. A statement discussed and approved by all working group members should support each guideline technically. This may include circulating the draft and receiving input from technical parties not present in the working group. All iterations necessary to bring about technical consensus should be explored. The final draft of this step, including the messages that will reach consumers, should then be pilot tested with consumer groups and modified to secure understanding by the target group. The results of the pilot tests should be used in establishing the revised guidelines.

The final set of guidelines and supporting technical statements should then be released for ample critical public review by all relevant groups. The support of international technical experts and relevant UN agencies may be helpful at this stage. Experience suggests that the Internet can be used to enhance input from consumer groups. Subsequent to final modifications resulting from the public consultation process, the FBDGs will be ready for final approval, publication in various formats, dissemination, and implementation for general use. The lower portion of Figure 110.2 provides a summary of potential end-users of the FBDGs.

The impact of FBDGs in modifying food intake patterns and the relevant public nutrition problems should be periodically assessed. Measures to enhance their applicability such as mass media and educational campaigns, incorporation into school curricula, and inclusion in other health promotion programs should be implemented. Based on periodic assessment, the guidelines should be reexamined and/or revised within a set period, normally every 5 to 10 years, to ensure that they remain current and scientifically valid.

Effectiveness and National Variation

Experience with FBDGs over the past decade suggests that they offer a feasible, effective, and sustainable approach to promote healthy eating of the population in general and to address nutrition problems in vulnerable groups. They foster a practical, consumer-oriented approach to reach specific nutritional goals for a given population. A focus on foods and food groups helps in the development of clear, easy-to-understand, behavioral messages suitable for the target audience. FBDGs often go beyond the remit of “foods”; for example they may promote a healthy weight, encourage physical activity, and provide advice about water and food safety. Guidelines are often further simplified into schematic representations of the agreed dietary advice such as the UK Eatwell Plate (18) and the USDA health pyramid (19) to provide greater clarity to consumers.

Importantly, FBDGs must facilitate choices for consumers that are consistent with their preferences, food culture, and economic resources. Typically, such guidelines recommend a minimum number of servings from each of four to seven basic food groups. FBDGs also commonly suggest the need to limit intake of certain food components, such as saturated and trans-fatty acids, added sugars, and salt. For example, one of the key recommendations of the US Dietary Guidelines is to “consume a variety of nutrientdense foods and beverages within and among the basic food groups while choosing foods that limit the intake of saturated and trans-fats, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol” (20). FBDGs must also take into account the needs of population subgroups, especially those at particular risk, and will often specify guidelines for these groups such as older people or women of childbearing age.

Food-based strategies offer many benefits that go beyond the prevention and control of nutrient deficiencies. For example, FBDGs

Help prevent and control both macro- and micronutrient deficiencies by addressing underlying causes

Support health promotion and preventive medicine

Should be cost effective and sustainable

Can be adapted to different cultural and dietary traditions and to strategies that are feasible at the local level

Address multiple nutrition problems simultaneously

Minimize the risk of toxicity and adverse nutrient interactions because the amounts of nutrients consumed are within usual physiologic levels

Support the role of breast-feeding and the special diet and care needs of infants and young children

Can foster the development of sustainable, environmentally sound, food production systems

May serve to alert agricultural planners to the need to protect the micronutrient content of soils and crops

Build partnerships among governments, consumer groups, the food industry, and other organizations to achieve the shared goals of overcoming nutrition-related health problems

Empower people to become more self-reliant using local resources

Provide opportunities for social interaction and enjoyment

Many nations have developed FBDGs for their populations and we have provided an example from each world region in Table 110.1. The FAO is compiling these as part of an online resource (21). Dietary guidelines from different countries tend to be similar in their purposes and uses, but the process of development can be distinct depending on the stakeholders involved. They are intended for use not only by health professionals but also by members of the general population and thus are mostly worded in simple, concrete terms. The similarity among national guidelines is striking: they all place an emphasis on balance, moderation (especially with regard to fat, sugar, salt, and alcohol), and variety and they all highlight the importance of consuming sufficient portions of fruits, vegetables, and grains. However, they also vary quite considerably, both in the wording used and the level of detail provided to the consumer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree