EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Begin by asking the patient about the nature, onset, and duration of the fasciculations. If the onset was sudden, ask about precipitating events such as exposure to pesticides. Pesticide poisoning, although uncommon, is a medical emergency requiring prompt and vigorous intervention. You may need to maintain airway patency, monitor the patient’s vital signs, give oxygen, and perform gastric lavage or induce vomiting.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, find out if he has experienced sensory changes, such as paresthesia, or any difficulty speaking, swallowing, breathing, or controlling bowel or bladder function. Ask him if he’s in pain.

Explore the patient’s medical history for neurologic disorders, cancer, and recent infections. Also, ask him about his lifestyle, especially stress at home, on the job, or at school.

Ask the patient about his dietary habits and for a recall of his food and fluid intake in the recent past because electrolyte imbalances may also cause muscle twitching.

Perform a physical examination, looking for fasciculations while the affected muscle is at rest. Observe and test for motor and sensory abnormalities, particularly muscle atrophy and weakness, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. If you note these signs and symptoms, suspect motor neuron disease, and perform a comprehensive neurologic examination.

Medical Causes

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Coarse fasciculations usually begin in the small muscles of the hands and feet and then spread to the forearms and legs. Widespread, symmetrical muscle atrophy and weakness may result in dysarthria; difficulty chewing, swallowing, and breathing; and, occasionally, choking and drooling.

- Bulbar palsy. Fasciculations of the face and tongue commonly appear early. Progressive signs and symptoms include dysarthria, dysphagia, hoarseness, and drooling. Eventually, weakness spreads to the respiratory muscles.

- Poliomyelitis (spinal paralytic). Coarse fasciculations, usually transient but occasionally persistent, accompany progressive muscle weakness, spasms, and atrophy. The patient may also exhibit decreased reflexes, paresthesia, coldness, and cyanosis in the affected limbs, bladder paralysis, dyspnea, elevated blood pressure, and tachycardia.

- Spinal cord tumors. Fasciculations may develop along with muscle atrophy and cramps, asymmetrically at first and then bilaterally as cord compression progresses. Motor and sensory changes distal to the tumor include weakness or paralysis, areflexia, paresthesia, and a tightening band of pain. Bowel and bladder control may be lost.

Other Causes

- Pesticide poisoning. Ingestion of organophosphate or carbamate pesticides commonly produces an acute onset of long, wavelike fasciculations and muscle weakness that rapidly progresses to flaccid paralysis. Other common effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of bowel and bladder control, hyperactive bowel sounds, and abdominal cramping. Cardiopulmonary findings include bradycardia, dyspnea or bradypnea, and pallor or cyanosis. Seizures, visual disturbances (pupillary constriction or blurred vision), and increased secretions (tearing, salivation, pulmonary secretions, or diaphoresis) may also occur.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as spinal X-rays, myelography, a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, and electromyography with nerve conduction velocity tests. Prepare the patient for laboratory tests such as serum electrolyte levels. Help the patient with progressive neuromuscular degeneration to cope with activities of daily living, and provide appropriate assistive devices.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the disease, its progression, and its treatment options. Instruct the patient how to use assistive devices. Refer him to support groups as indicated.

Pediatric Pointers

Fasciculations, particularly of the tongue, are an important early sign of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease.

REFERENCES

De Beaumont, L., Mongeon, D., Tremblay, S., Messier, J., Prince, F., Leclerc, S., … Théoret, H. (2011). Persistent motor system abnormalities in formerly concussed athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 46(3),234–240.

De Beaumont, L., Theoret, H., Mongeon, D., Messier, J., Leclerc, S., Tremblay, S., … Lassonde, M. (2009). Brain function decline in healthy retired athletes who sustained their last sports concussion in early adulthood. Brain, 132, 695–708.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of excessive tiredness, a lack of energy, or exhaustion accompanied by a strong desire to rest or sleep. This common symptom is distinct from weakness, which involves the muscles, but may occur with it.

Fatigue is a normal and important response to physical overexertion, prolonged emotional stress, and sleep deprivation. However, it can also be a nonspecific symptom of a psychological or physiologic disorder — especially viral or bacterial infection and endocrine, cardiovascular, or neurologic disease.

Fatigue reflects hypermetabolic and hypometabolic states in which nutrients needed for cellular energy and growth are lacking because of overly rapid depletion, impaired replacement mechanisms, insufficient hormone production, or inadequate nutrient intake or metabolism.

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a careful history to identify the patient’s fatigue pattern. Fatigue that worsens with activity and improves with rest generally indicates a physical disorder; the opposite pattern, a psychological disorder. Fatigue lasting longer than 4 months, constant fatigue that’s unrelieved by rest, and transient exhaustion that quickly gives way to bursts of energy are other findings associated with psychological disorders.

Ask about related symptoms and recent viral or bacterial illness or stressful changes in lifestyle. Explore nutritional habits and appetite or weight changes. Carefully review the patient’s medical and psychiatric history for chronic disorders that commonly produce fatigue, such as anemia and sleep disorders. Ask about a family history of such disorders.

Obtain a thorough drug history, including prescription and nonprescription drugs, noting the use of any drug with fatigue as an adverse effect. Ask about alcohol and drug use patterns. Determine the patient’s risk for carbon monoxide poisoning, and inquire as to whether the patient has a carbon monoxide detector.

Observe the patient’s general appearance for overt signs of depression or organic illness. Is he unkempt or expressionless? Does he appear tired or sickly or have a slumped posture? If warranted, evaluate his mental status, noting especially mental clouding, attention deficits, agitation, or psychomotor retardation.

Medical Causes

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In addition to fatigue, AIDS may cause a fever, night sweats, weight loss, diarrhea, and a cough, followed by several concurrent opportunistic infections.

- Adrenocortical insufficiency. Mild fatigue, the hallmark of adrenocortical insufficiency, initially appears after exertion and stress but later becomes more severe and persistent. Weakness and weight loss typically accompany GI disturbances, such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, and chronic diarrhea; hyperpigmentation; orthostatic hypotension; and a weak, irregular pulse.

- Anemia. Fatigue following mild activity is commonly the first symptom of anemia. Associated findings vary but generally include pallor, tachycardia, and dyspnea.

- Anxiety. Chronic, unremitting anxiety invariably produces fatigue, typically characterized as nervous exhaustion. Other persistent findings include apprehension, indecisiveness, restlessness, insomnia, trembling, and increased muscle tension.

- Cancer. Unexplained fatigue is commonly the earliest sign of cancer. Related findings reflect the type, location, and stage of the tumor and typically include pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, abnormal bleeding, and a palpable mass.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome. Chronic fatigue syndrome, whose cause is unknown, is characterized by incapacitating fatigue. Other findings are a sore throat, myalgia, and cognitive dysfunction. Diagnostic criteria have been determined, but research and data collection continue. These findings may alter the diagnostic criteria.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The earliest and most persistent symptoms of COPD are progressive fatigue and dyspnea. The patient may also experience a chronic and usually productive cough, weight loss, barrel chest, cyanosis, slight dependent edema, and poor exercise tolerance.

- Depression. Persistent fatigue unrelated to exertion nearly always accompanies chronic depression. Associated somatic complaints include a headache, anorexia (occasionally, increased appetite), constipation, and sexual dysfunction. The patient may also experience insomnia, slowed speech, agitation or bradykinesia, irritability, loss of concentration, feelings of worthlessness, and persistent thoughts of death.

- Diabetes mellitus. Fatigue, the most common symptom in diabetes mellitus, may begin insidiously or abruptly. Related findings include weight loss, blurred vision, polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia.

- Heart failure. Persistent fatigue and lethargy characterize heart failure. Left-sided heart failure produces exertional and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and tachycardia. Right-sided heart failure produces jugular vein distention and, possibly, a slight but persistent nonproductive cough. In both types, mental status changes accompany later signs and symptoms, including nausea, anorexia, weight gain and, possibly, oliguria. Cardiopulmonary findings include tachypnea, inspiratory crackles, palpitations and chest tightness, hypotension, a narrowed pulse pressure, a ventricular gallop, pallor, diaphoresis, clubbing, and dependent edema.

- Hypercortisolism. Hypercortisolism typically causes fatigue, related in part to accompanying sleep disturbances. Unmistakable signs include truncal obesity with slender extremities, buffalo hump, moon face, purple striae, acne, and hirsutism; increased blood pressure and muscle weakness are other findings.

- Hypothyroidism. Fatigue occurs early in hypothyroidism, along with forgetfulness, cold intolerance, weight gain, metrorrhagia, and constipation.

- Infection. With chronic infection, fatigue is commonly the most prominent symptom — and sometimes the only one. A low-grade fever and weight loss may accompany signs and symptoms that reflect the type and location of infection, such as burning upon urination or swollen, painful gums. Subacute bacterial endocarditis is an example of a chronic infection that causes fatigue and acute hemodynamic decompensation.

With acute infection, brief fatigue typically accompanies a headache, anorexia, arthralgia, chills, a high fever, and such infection-specific signs as a cough, vomiting, or diarrhea.

- Lyme disease. In addition to fatigue and malaise, signs and symptoms of Lyme disease include an intermittent headache, a fever, chills, an expanding red rash, and muscle and joint aches. In later stages, patients may suffer from arthritis, fluctuating meningoencephalitis, and cardiac abnormalities, such as a brief, fluctuating atrioventricular heart block.

- Malnutrition. Easy fatigability is common in patients with protein-calorie malnutrition, along with lethargy and apathy. Patients may also exhibit weight loss, muscle wasting, sensations of coldness, pallor, edema, and dry, flaky skin.

- Metabolic syndrome. Fatigue is a common complaint of patients with metabolic syndrome, especially those who are obese and have unregulated blood glucose levels. Metabolic syndrome, also known as syndrome X, is a collective group of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors that predisposes the patient to heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Four risk factors — central obesity, elevated blood glucose levels, abnormal triglyceride and HDL levels, and hypertension — characterize metabolic syndrome. Patients may also feel sluggish or depressed, have difficulty losing weight, and have a waddling gait.

- Myasthenia gravis. The cardinal symptoms of myasthenia gravis are easy fatigability and muscle weakness, which worsen as the day progresses. They also worsen with exertion and abate with rest. Related findings depend on the specific muscles affected.

- Renal failure. Acute renal failure commonly causes sudden fatigue, drowsiness, and lethargy. Oliguria, an early sign, is followed by severe systemic effects: an ammonia breath odor, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and dry skin and mucous membranes. Neurologic findings include muscle twitching and changes in the patient’s personality and level of consciousness, possibly progressing to seizures and coma.

With chronic renal failure, insidious fatigue and lethargy occur with marked changes in all body systems, including GI disturbances, an ammonia breath odor, Kussmaul’s respirations, bleeding tendencies, poor skin turgor, severe pruritus, paresthesia, visual disturbances, confusion, seizures, and coma.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus. Fatigue usually occurs along with generalized aching, malaise, a low-grade fever, a headache, and irritability. Primary signs and symptoms include joint pain and stiffness, a butterfly rash, and photosensitivity. Also common are Raynaud’s phenomenon, patchy alopecia, and mucous membrane ulcers.

- Valvular heart disease. All types of valvular heart disease commonly produce progressive fatigue and a cardiac murmur. Additional signs and symptoms vary but generally include exertional dyspnea, a cough, and hemoptysis.

Other Causes

- Carbon monoxide poisoning. Fatigue occurs along with a headache, dyspnea, and confusion and can eventually progress to unconsciousness and apnea.

- Drugs. Fatigue may result from various drugs, notably antihypertensives, sedatives, and antihistamines. In those receiving cardiac glycoside therapy, fatigue may indicate toxicity.

- Surgery. Most types of surgery cause temporary fatigue, probably due to the combined effects of hunger, anesthesia, and sleep deprivation.

Special Considerations

If fatigue results from organic illness, help the patient determine which daily activities he may need help with and how he should pace himself to ensure sufficient rest. You can help him reduce chronic fatigue by alleviating pain, which may interfere with rest, or nausea, which may lead to malnutrition. He may benefit from referral to a community health nurse or housekeeping service. If fatigue results from a psychogenic cause, refer him for psychological counseling.

Patient Counseling

Educate the patient about lifestyle modifications, including diet and exercise. Stress the importance of pacing his activities and planning rest periods. Discuss stress management techniques.

Pediatric Pointers

When evaluating a child for fatigue, ask his parents if they’ve noticed a change in his activity level. Fatigue without an organic cause occurs normally during accelerated growth phases in preschool-age and prepubescent children.

However, psychological causes of fatigue must be considered — for example, a depressed child may try to escape problems at home or school by taking refuge in sleep. In the pubescent child, consider the possibility of drug abuse, particularly of hypnotics and tranquilizers.

Geriatric Pointers

Always ask older patients about fatigue because this symptom may be insidious and mask more serious underlying conditions in this age group. Temporal arthritis, which is much more common in people older than age 60, is usually characterized by fatigue, weight loss, jaw claudication, proximal muscle weakness, a headache, vision disturbances, and associated anemia.

REFERENCES

Froyd, C., Millet, G. Y., & Noakes, T. D. (2012). The development of peripheral fatigue and short-term recovery during self-paced high-intensity exercise. Journal of Physiology, 591, 1339–1346.

Goodall, S., Gonzalez-Alonso, J., Ali, L., Ross, E. Z., & Romer, L. M. (2012). Supraspinal fatigue after normoxic and hypoxic exercise in humans. Journal of Physiology, 590, 2767–2782.

Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence, the involuntary passage of feces, follows a loss or an impairment of external anal sphincter control. It can result from many GI, neurologic, and psychological disorders; the effects of drugs; or surgery. In some patients, it may even be a purposeful manipulative behavior.

Fecal incontinence may be temporary or permanent; its onset may be gradual, as in dementia, or sudden, as in spinal cord trauma. Although usually not a sign of severe illness, it can greatly affect the patient’s physical and psychological well-being.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient with fecal incontinence about its onset, duration, and severity and about any discernible pattern — for example, does it occur at night or only with episodes of diarrhea? Note the frequency, consistency, and volume of stools passed within the past 24 hours and obtain a stool sample. Focus your history taking on GI, neurologic, and psychological disorders.

Let the history guide your physical examination. If you suspect a brain or spinal cord lesion, perform a complete neurologic examination. (See Neurologic Control of Defecation.) If a GI disturbance seems likely, inspect the abdomen for distention, auscultate for bowel sounds, and percuss and palpate for a mass. Inspect the anal area for signs of excoriation or infection. If not contraindicated, check for fecal impaction, which may be associated with incontinence.

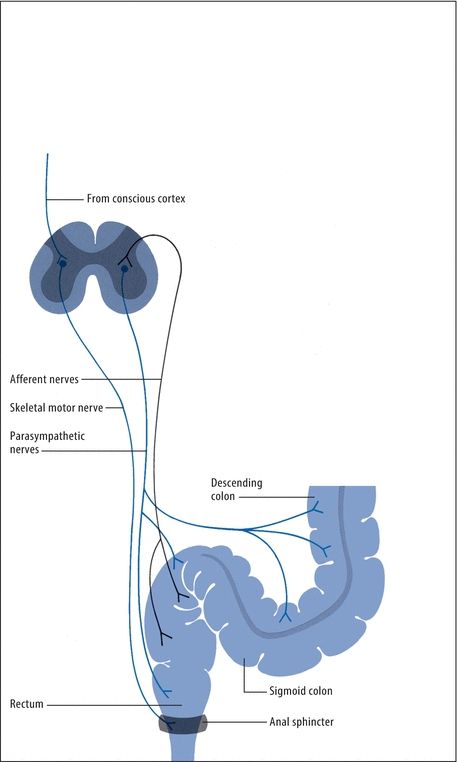

Neurologic Control of Defecation

Three neurologic mechanisms normally regulate defecation: the intrinsic defecation reflex in the colon, the parasympathetic defecation reflex involving sacral segments of the spinal cord, and voluntary control. Here’s how they interact.

Fecal distention of the rectum activates the relatively weak intrinsic reflex, causing afferent impulses to spread through the myenteric plexus, initiating peristalsis in the descending and sigmoid colon and rectum. Subsequent movement of feces toward the anus causes receptive relaxation of the internal anal sphincter.

To ensure defecation, the parasympathetic reflex magnifies the intrinsic reflex. Stimulation of afferent nerves in the rectal wall propels impulses through the spinal cord and back to the descending and sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus to intensify peristalsis.

However, fecal movement and internal sphincter relaxation cause immediate contraction of the external anal sphincter and temporary fecal retention. At this point, conscious control of the external sphincter either prevents or permits defecation. Except in infants or neurologically impaired patients, this voluntary mechanism further contracts the sphincter to prevent defecation at inappropriate times or relaxes it and allows defecation to occur.

Medical Causes

- Constipation. It may seem odd that constipation could be a cause of fecal incontinence, but it occurs when stool becomes impacted in the rectum, causing the rectal muscles to stretch and weaken. Liquid stool is then able to seep around the impaction and the patient is unable to control it.

- Dementia. Any chronic degenerative brain disease can produce fecal as well as urinary incontinence. Associated signs and symptoms include impaired judgment and abstract thinking, amnesia, emotional lability, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, aphasia or dysarthria and, possibly, diffuse choreoathetoid movements.

- Head trauma. Disruption of the neurologic pathways that control defecation can cause fecal incontinence. Additional findings depend on the location and severity of the injury and may include a decreased level of consciousness, seizures, vomiting, and a wide range of motor and sensory impairments.

- Inflammatory bowel disease. Nocturnal fecal incontinence occurs occasionally with diarrhea. Related findings include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, blood in the stools, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

- Muscle damage. Fecal incontinence can occur when there is damage to the internal and external anal sphincter muscles and stool is able to leak out. This may result from childbirth or hemorrhoid surgery or more complex procedures involving the anus or rectum.

- Nerve damage. Damage to the nerves that control the sensation to defecate could result in fecal incontinence. This may occur from injury during childbirth, straining to pass stool, or spinal cord injury as well as from certain diseases, such as diabetes or multiple sclerosis.

- Rectovaginal fistula. Fecal incontinence occurs in tandem with uninhibited passage of flatus.

- Spinal cord lesions. Any lesion that causes compression or transsection of sensorimotor spinal tracts can lead to fecal incontinence. Incontinence may be permanent, especially with severe lesions of the sacral segments. Other signs and symptoms reflect motor and sensory disturbances below the level of the lesion, such as urinary incontinence, weakness or paralysis, paresthesia, analgesia, and thermanesthesia.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Chronic laxative abuse may cause insensitivity to a fecal mass or loss of the colonic defecation reflex.

- Surgery. Pelvic, prostate, or rectal surgery occasionally produces temporary fecal incontinence. Colostomy or ileostomy causes permanent or temporary fecal incontinence.

Special Considerations

Maintain proper hygienic care, including control of foul odors. Provide meticulous skin care, and instruct the patient to do the same if he’s able. Also, provide emotional support for the patient because he may feel deep embarrassment. For the patient with intermittent or temporary incontinence, encourage Kegel exercises to strengthen abdominal and perirectal muscles. For the neurologically capable patient with chronic incontinence, provide bowel retraining. Effective treatment depends on the cause and severity of fecal incontinence. Treatment may include dietary changes, medication, or surgery.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in the essential techniques of bowel retraining. Explain how to perform Kegel exercises and teach him how to maintain proper hygiene.

Pediatric Pointers

Fecal incontinence is normal in infants and may occur temporarily in young children who experience stress-related psychological regression or a physical illness associated with diarrhea. Children with chronic constipation may develop encopresis, a term for fecal incontinence in children usually who are older than 4 years. Liquid stool seeps around hard, dry, impacted stool, causing staining in the child’s clothes. Pediatric fecal incontinence can also result from myelomeningocele.

Geriatric Pointers

Fecal incontinence is an important factor when long-term care is considered for an elderly patient. Leakage of liquid fecal material is especially common in males. Age-related changes affecting smooth muscle cells of the colon may change GI motility and lead to fecal incontinence. Before age is determined to be the cause, however, any pathology must be ruled out.

REFERENCES

Bongers, M. E., van Dijk, M., Benninga, M. A., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2009). Health related quality of life in children with constipation associated fecal incontinence. Journal of Pediatrics, 154, 749–753.

Wald, A., & Sigurdsson, L., (2011). Quality of life in children and adults with constipation. Best Practice Research in Clinical Gastroenterology, 25, 19–27.

Fetor Hepaticus

Fetor hepaticus — a distinctive musty, sweet breath odor — characterizes hepatic encephalopathy, a life-threatening complication of severe liver disease. The odor results from the damaged liver’s inability to metabolize and detoxify mercaptans produced by bacterial degradation of methionine, a sulfurous amino acid. These substances circulate in the blood are expelled by the lungs and flavor the breath.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect fetor hepaticus, quickly determine the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). If he’s comatose, evaluate his respiratory status. Prepare to intubate and provide ventilatory support, if necessary. Start a peripheral I.V. line for fluid administration, begin cardiac monitoring, and insert an indwelling urinary catheter to monitor output. Obtain arterial and venous samples for analysis of blood gases, ammonia, and electrolytes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree