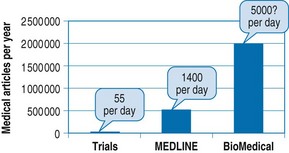

Chapter 33 We can summarize the EBM approach as a four-step process (Straus et al 2005): • asking answerable clinical questions • searching for the best research evidence • critically appraising the evidence for its validity and relevance Important themes to develop are trying to keep up to date and the problem of overcoming the increasing world literature: over 1500 new medical research articles are published daily (Fig. 33.1). You might stop and ask your learners to reflect on how they currently learn and keep up to date. You might also ask them how much time is being spent on each process. Activities usually identified include attending lectures and conferences, reading articles in journals, tutorials, textbooks, clinical guidelines, clinical practice, small-group learning, study groups, using electronic resources and speaking to colleagues and specialists. There is no right or wrong way to learn; a mixture of all of these methods will be beneficial in the overall process of gathering information. Samples of an introductory presentation are available free from the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine website (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine downloads, www.cebm.net). Population/patient: what is the disease problem? Intervention/indicator: what main treatment is being considered? Comparator/control: is this in relation to an alternative? Outcome: what are the main outcomes of interest to the patient? (And sometimes we add a T for the Time to the outcome, e.g. 5-year survival). Clinical findings: how to interpret findings from the history and examination Aetiology: the causes of diseases Diagnosis: what tests are going to aid you in the diagnosis? Prognosis: the probable course of the disease over time and the possible outcomes Therapy: which treatment are you going to choose based on beneficial outcomes, harms, cost and your patient’s values? Prevention: primary and secondary risk factors which may or may not lead to an intervention Cost-effectiveness: is one intervention more cost effective than another? Quality of life: what effect does the intervention have on the quality of your patient’s life? Phenomena: the qualitative or narrative aspects of the problem Resources which you will need are the following:

Evidence-based medicine

Introduction

Introductory lecture: an hour on raising awareness

Evaluate your own learning strategies and your learners

Asking answerable questions

Searching for the evidence

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine