Chapter Seven

Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

![]() Define clinical practice guidelines.

Define clinical practice guidelines.

![]() Define evidence-based medicine.

Define evidence-based medicine.

![]() Discuss the role of the pharmacist in development and use of these evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

Discuss the role of the pharmacist in development and use of these evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

![]() Explain the methodology for development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

Explain the methodology for development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

![]() Describe the GRADE system for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

Describe the GRADE system for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

![]() Describe the AGREE II instrument for evaluating clinical practice guidelines.

Describe the AGREE II instrument for evaluating clinical practice guidelines.

![]() Identify the key issues involved in the implementation of clinical practice guidelines.

Identify the key issues involved in the implementation of clinical practice guidelines.

![]() Identify sources of published clinical practice guidelines.

Identify sources of published clinical practice guidelines.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction

![]() Clinical practice guidelines are recommendations for optimizing patient care that are developed by systematically reviewing the evidence and assessing the benefits and harms of health care interventions.1 These interventions may include not only medications but other types of therapy, such as radiation, surgery, and physical therapy. Clinical practice guidelines are developed by a variety of groups and organizations including federal and state government, professional associations, managed care organizations, third-party payers, quality assurance organizations, and utilization review groups. The purpose of the guidelines, methods used to develop them, format of the documents, and the strategies for implementation vary widely. Considering the potential for clinical practice guidelines to influence thousands to millions of decisions on medical interventions, it is incumbent for all health care practitioners to be thoroughly familiar with criteria to judge the validity of guidelines and to be skilled in determining their appropriate application.

Clinical practice guidelines are recommendations for optimizing patient care that are developed by systematically reviewing the evidence and assessing the benefits and harms of health care interventions.1 These interventions may include not only medications but other types of therapy, such as radiation, surgery, and physical therapy. Clinical practice guidelines are developed by a variety of groups and organizations including federal and state government, professional associations, managed care organizations, third-party payers, quality assurance organizations, and utilization review groups. The purpose of the guidelines, methods used to develop them, format of the documents, and the strategies for implementation vary widely. Considering the potential for clinical practice guidelines to influence thousands to millions of decisions on medical interventions, it is incumbent for all health care practitioners to be thoroughly familiar with criteria to judge the validity of guidelines and to be skilled in determining their appropriate application.

Development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines have many characteristics in common with traditional activities performed by drug information specialists, such as evaluation of new drugs for formulary consideration, medication use evaluation, and quality improvement. Many of the skills required for guideline development are required of pharmacists, including clear specific definition of clinical questions, literature search and evaluation, epidemiology, biostatistics, clinical expertise, writing, editing, and formatting. Drug information specialists benefit from the use of clinical practice guidelines as information resources for their work, and based on their skills they are logical professionals to participate in guideline development and implementation. Pharmacists and health care professionals should also be using clinical practice guidelines whenever possible in their practices.

The primary attraction for all health care professionals in properly developed, valid clinical practice guidelines is that they provide a concise summary of current best evidence on what works and what does not when considering specific health care interventions. New information and new technology in health care are developed at a rapid pace. It is very difficult for individual practitioners to systematically evaluate the benefits and risks of all new technology, including new medications. By presenting a summary of best evidence, guidelines assist the practitioner in decision making for specific patients and also facilitate discussion of care options most consistent with individual patient needs and preferences. Guidelines may also enhance provider communication and continuity of care, especially when decisions are made by multiple providers in different care settings.2

A significant time lag occurs in getting research information into practice, and one of the goals of development and implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines is to help speed up the process of getting evidence into practice. There are several examples of treatments that have been well studied and proven effective but are substantially underutilized and interventions that have been proven ineffective or harmful but continue to be done.3 One of the goals of development and implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines is to help speed up the process of getting evidence into practice.

Clinical practice guidelines to assist with health care decision making and to identify indicators for monitoring quality of care are frequently mentioned in connection with efforts to improve quality and efficiency of services. The key issues in reforming the United States (U.S.) health care system are access to care, cost, and quality. Quality and safety are a major focus as evidenced by landmark reports published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) regarding quality of care problems in the United States, recommendations to focus on improvements in patient safety, and recommendations to reduce preventable medical errors.4–7 The central concepts in these reports and recommendations relate to using the best available evidence, providing decision support tools, use of informatics, and participation of patients in health care decisions and responsibilities. The most recent reports from the IOM deal specifically with standards for clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research, and providing care at a lower cost.1,8,9 All of these documents and standards highlight improvements in technology, information technology, quality of access to electronic records, and greater ability to use the data from processes of care to provide valuable new information to learn what works best. These concepts are central to improving the validity and usefulness of clinical practice guidelines.

Methods currently recommended as the most valid for development of clinical practice guidelines emphasize an evidence-based approach, formal quantitative techniques to calculate risks and benefits, and incorporation of the patient’s preference. The concepts of an evidence-based approach and use of methods to grade the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations are critical elements that will be reviewed in more detail in this chapter. The evidence-based health care movement and the implementation of continuous quality improvement (CQI) programs stimulated growth in guideline development. Advancements continue to be made in methods of evaluation and summarizing the best available evidence. Development of information databases of systematic reviews and new informatics resources has facilitated the production of clinical practice guidelines and improved access to this information.

This chapter presents a review of the background of clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based medicine; review evidence-based methods for guideline development, evaluation, and implementation; and provide directions to locate sources of guidelines.

Evidence-Based Medicine and Clinical Practice Guidelines

![]() Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a philosophy of practice and an approach to decision making in the clinical care of patients that involves making individual patient care decisions based on the best currently available evidence.10 The practice of EBM refers to integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available published clinical evidence from systematic research. EBM is often mistaken for, or reduced to, just one of its several components, critical appraisal of the literature. However, EBM requires both clinical expertise and an intimate knowledge of the individual patient’s situation, beliefs, priorities, and values to be useful. External evidence must be used to inform, but not replace, individual clinical expertise. It is clinical expertise that determines if the external evidence may be applied to the individual patient and, if so, how it should be used in decision making by the patient and the health care provider. The development and application of clinical practice guidelines are among the tools used in EBM. In fact, the first published use of the term evidence-based was in the context of clinical guidelines.11 An understanding of EBM is necessary to understand recommended methods for production and implementation of guidelines.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a philosophy of practice and an approach to decision making in the clinical care of patients that involves making individual patient care decisions based on the best currently available evidence.10 The practice of EBM refers to integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available published clinical evidence from systematic research. EBM is often mistaken for, or reduced to, just one of its several components, critical appraisal of the literature. However, EBM requires both clinical expertise and an intimate knowledge of the individual patient’s situation, beliefs, priorities, and values to be useful. External evidence must be used to inform, but not replace, individual clinical expertise. It is clinical expertise that determines if the external evidence may be applied to the individual patient and, if so, how it should be used in decision making by the patient and the health care provider. The development and application of clinical practice guidelines are among the tools used in EBM. In fact, the first published use of the term evidence-based was in the context of clinical guidelines.11 An understanding of EBM is necessary to understand recommended methods for production and implementation of guidelines.

The term evidence-based medicine was first used by physicians at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. This group, the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, published a description of what they considered a new paradigm for medical practice and teaching.12 Their article presented their views on changes that were occurring in medical practice relating to the use of medical literature to more effectively guide decision making. They stated that the foundation for the paradigm shift rested in significant advances in clinical research, such as the development of the randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis.

The practice of EBM has been described as focusing on five linked activities: (1) converting the information need into a clearly defined answerable clinical question, (2) conducting a search for the best available evidence for the problem, (3) critically appraising the validity, impact, and applicability of the evidence, (4) incorporating the critical appraisal with clinical expertise and the patient’s unique characteristics, and (5) evaluating effectiveness and efficiency in executing the first four activities and identify ways to improve them.13 Those who are familiar with the literature in drug information practice will recognize that these activities are remarkably similar to the systematic approach to drug information requests as outlined by Watanabe and colleagues in 1975.14 This process is still very similar to the approach used to answer drug information questions today.

Following their original paper on EBM,12 the lead individuals in the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group published a description of how evidence-based care practitioners should be trained to locate, evaluate, and apply the best evidence.15 This description recognizes that not all practitioners will have the time or an interest in using primary literature. The description notes that sources of appropriately preappraised evidence may be used. Examples of preappraised evidence would include clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews that have been produced with evidence-based methods. These authors noted that skill in interpreting the medical literature is still necessary to judge the quality of the preappraised resources, to know when the recommendations in the preappraised resources are not applicable to selected patients, and to use the original literature when preappraised resources are unavailable.15

In a review of the philosophy of EBM, Eddy described an approach that is similar to the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group.11 The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group’s original description of the practice is referred to as evidence-based individual decision making. Eddy refers to a second approach to EBM as being evidence-based guidelines. This second approach has four important features: (1) small, specially trained groups should analyze the evidence and develop the guideline, (2) an explicit, rigorous process should be used, (3) the guideline should not be specific to an individual patient but rather should be applicable to a class or group of patients, and (4) the guideline should indirectly help, guide, or motivate health care providers to deliver certain types of care to people, not directly determine the care for a specific patient.11 Eddy went on to explain that the most appropriate definition of EBM is a combination of these two approaches. The combination provides for medical practice that will achieve the most efficient and effective use of evidence.

Health care professionals face the complicated reality of constantly changing and increasing medical knowledge. To practice effective, high quality medicine, it is not necessary to memorize vast quantities of information; what is necessary are the skills to acquire and critically assess the specific information that is necessary to make clinical decisions.16 The philosophy of EBM is consistent with the philosophy of clinical practice guidelines. The decision-making process of EBM is supported by access and use of clinical practice guidelines.

Guideline Development Methods

A thorough understanding of the methodology used for clinical practice guideline development is critical for health care practitioners. Although relatively few practitioners actually participate in guideline development, this understanding will prepare them for involvement in appropriate evaluation and implementation of these guidelines. ![]() Evaluation of the quality of a guideline and the appropriateness of its use in a given setting depends primarily on an ability to distinguish methods that minimize potential biases in development. A lack of understanding of the requirements for guideline development could lead to inappropriate interpretation, or acceptance of inappropriate levels of enforcement of biased guideline recommendations. Application of biased guidelines may result in provision of ineffective or harmful therapy. Because of the central importance of guideline development methods, a significant portion of this chapter is devoted to this topic.

Evaluation of the quality of a guideline and the appropriateness of its use in a given setting depends primarily on an ability to distinguish methods that minimize potential biases in development. A lack of understanding of the requirements for guideline development could lead to inappropriate interpretation, or acceptance of inappropriate levels of enforcement of biased guideline recommendations. Application of biased guidelines may result in provision of ineffective or harmful therapy. Because of the central importance of guideline development methods, a significant portion of this chapter is devoted to this topic.

Although many organizations produce clinical practice guidelines, there are no uniformly endorsed standards for their development. In 2008, the IOM was charged with developing and promoting standards for systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.1 Two committees were formed: the Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research and the Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. In 2011, the committees published their proposed standards for systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research8 and for developing rigorous, trustworthy clinical practice guidelines.1

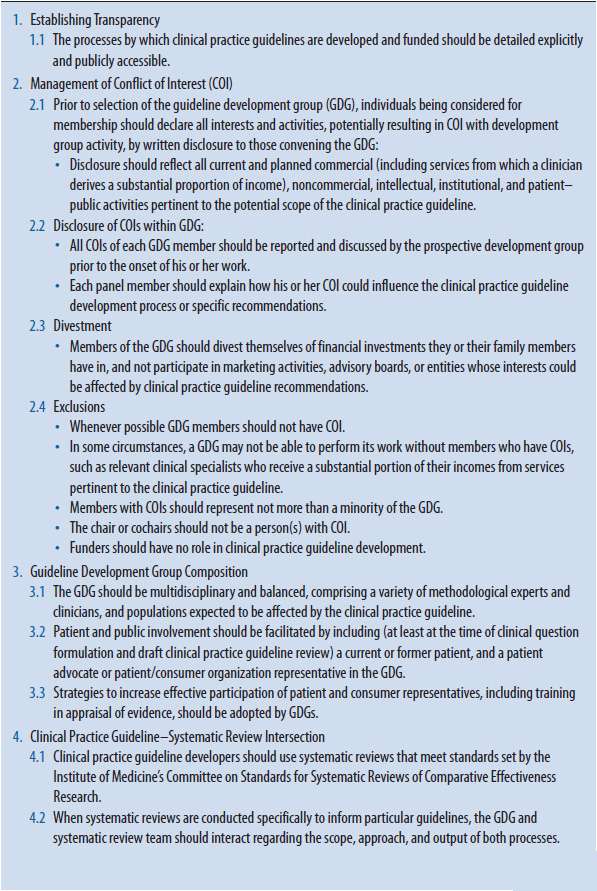

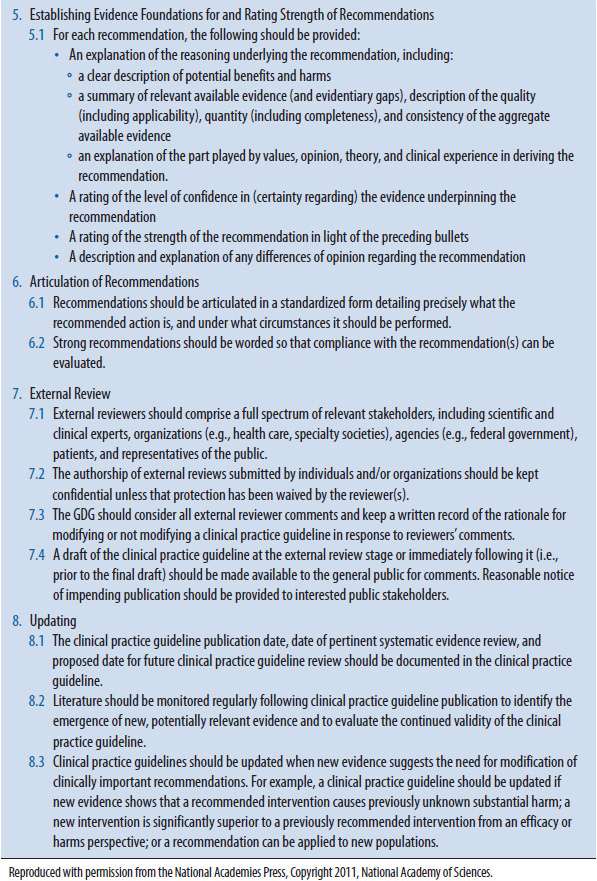

The IOM proposed eight standards (Table 7–1) for developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. The major steps in their proposed standards include the following (additional details for each of these steps are described below)1:

TABLE 7–1. STANDARDS FOR DEVELOPING TRUSTWORTHY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES1

![]() Establish transparency.

Establish transparency.

![]() Manage conflict of interest.

Manage conflict of interest.

![]() Establish a multidisciplinary guideline development group.

Establish a multidisciplinary guideline development group.

![]() Conduct a systematic review for qualifying evidence.

Conduct a systematic review for qualifying evidence.

![]() Establish evidence foundations for and rate strength of recommendations.

Establish evidence foundations for and rate strength of recommendations.

![]() Articulate recommendations.

Articulate recommendations.

![]() Conduct an external review.

Conduct an external review.

![]() Establish a plan for updating the guideline.

Establish a plan for updating the guideline.

ESTABLISH TRANSPARENCY

The standard for this step calls for the processes by which the guideline is developed and funded to be transparent, i.e., how the guideline is developed and funded should be explicitly detailed and the public should have access to this information. Transparency helps users understand how the recommendations were made and who developed them. The clinical experience of the guideline development group’s members and potential conflicts of interest (COIs) should be stated as well.1

MANAGE CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The standard for this step provides details for managing of potential COIs by members of the guideline development group. COIs not only include financial COIs, but also intellectual conflicts that may occur as a result of previous research published by the individual, institutional COIs, and patient–public activities.1

Individuals being considered for membership on a guideline development panel should be asked to declare potential COIs. Individuals with a potential conflict of interest may still be considered for participation on a panel depending on the type and degree of conflict, along with appropriate levels of management and disclosure.17 Rigid adherence to exclusion of any possible conflict could result in guideline panels excluding the majority of individuals with the critical expertise needed. Surveys have shown the need for attention to this issue as guideline authors frequently have some relationship with pharmaceutical manufacturers.18 Controversies over the sponsorship of guideline development and publication19 and potential COIs by panel members20 have occurred.

The American College of Chest Physicians is one prominent guideline development group that placed an emphasis on dealing with conflict of interest in their most recent edition of their guideline on Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis.21 The primary leadership and responsibility for authorship of each article was assigned to a methodologist with no COIs, who in most cases was also a practicing physician, but not an expert on the topic of thrombosis. Some experts nominated to participate in a panel were not accepted because of the magnitude of financial COIs. Panel members who had conflicts, either financial or intellectual, could be limited to some extent in their participation in discussions and could not participate in the final process of decisions regarding the direction or strength of a recommendation.21,22

ESTABLISH A MULTIDISCIPLINARY GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT GROUP

The standard for this step relates to the composition of the group to develop the guideline and includes patient and public involvement in the process. Patient involvement is especially important in helping to formulate and prioritize the questions to be addressed by the guideline. This standard also provides direction for how to obtain input from panel members, reach consensus, and make decisions through the group process.1

The development of a clinical practice guideline should involve a multidisciplinary team. Ideally, all groups that have a stake in the development and implementation of a guideline are represented in the process. Participants should include physicians with special expertise in the condition being considered; primary care practitioners involved in the treatment of patients with the identified condition; representatives of other health care disciplines involved in providing care for the identified condition (e.g., pharmacy, physical therapy, respiratory therapy, nursing, occupational therapy, social work, dentistry); experts in research methods applicable to the topic; individuals, such as drug information specialists, with expertise in conducting a systematic search for evidence; individuals with administrative, health services, economics, and other health care systems expertise; and patient representatives or caregivers. Organizational skills, project management, and editorial ability are also key to successfully developing a guideline.

Case Study 7–1

You have been selected to lead the formation of a panel to be involved in the development of clinical practice guidelines in your institution. No additional information or guidance has been provided to you. You would like to follow the Institute of Medicine’s proposed process for developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. As you sit in your office thinking about the many different activities that are going to be required of this panel, what are the first three steps that should be performed and what do they entail?

![]()

CONDUCT A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW FOR QUALIFYING EVIDENCE

The standard for this step acknowledges the overlap between clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews (see Chapter 5 for more information on systematic reviews). It recognizes that systematic reviews are important for preparing a synthesis of evidence for the guideline development group to use in formulating recommendations that will be based on the best and most complete available evidence.1 This standard recommends that clinical practice guideline developers conduct systematic reviews that meet the standards recommended in the IOM’s previously mentioned companion publication for systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research. A few key steps in the companion publication for systematic reviews of comparative research include the following (these are described in more detail below)8:

![]() Select an appropriate topic for creation of a guideline.

Select an appropriate topic for creation of a guideline.

![]() Define the clinical questions to be addressed.

Define the clinical questions to be addressed.

![]() Determine the study screening selection criteria.

Determine the study screening selection criteria.

![]() Conduct a systematic search for evidence.

Conduct a systematic search for evidence.

![]() Critically appraise individual studies (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Critically appraise individual studies (see Chapters 4 and 5).

![]() Synthesize the body of evidence.

Synthesize the body of evidence.

Select an Appropriate Topic for Creation of a Guideline

Selection of a topic for guideline development has aspects in common with selection of topics for a medication use evaluation program, or in a broader sense for any quality improvement program (see Chapter 14). Considering that guidelines are intended to improve the quality of care process and outcomes of care, it is important to consider the potential to achieve this improvement when a topic is chosen. As with a clinical management decision, the potential benefits of development and implementation of a guideline should be assessed. Disease states with the maximum potential for benefit from guideline development and implementation share common characteristics including the following:

![]() High prevalence

High prevalence

![]() High frequency and/or severity of associated morbidity or mortality

High frequency and/or severity of associated morbidity or mortality

![]() Availability of high-quality evidence for the efficacy of treatments that reduce morbidity or mortality

Availability of high-quality evidence for the efficacy of treatments that reduce morbidity or mortality

![]() Feasibility of implementation of the treatment based on expertise and other resources required

Feasibility of implementation of the treatment based on expertise and other resources required

![]() Potential cost-effectiveness

Potential cost-effectiveness

![]() Evidence that current practice is not optimal

Evidence that current practice is not optimal

![]() Evidence of practice variation; patients with similar characteristics are provided with different services or a substantially different frequency of services in different locations

Evidence of practice variation; patients with similar characteristics are provided with different services or a substantially different frequency of services in different locations

![]() Availability of personnel, expertise, and resources to develop and implement the practice guideline

Availability of personnel, expertise, and resources to develop and implement the practice guideline

As an example, the AHA identified the following reasons for developing evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women23:

![]() Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death of women in the United States.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death of women in the United States.

![]() It is essential that coronary heart disease (CHD) be prevented because CHD is often fatal, and the majority of women who die suddenly have not had any previous symptoms.

It is essential that coronary heart disease (CHD) be prevented because CHD is often fatal, and the majority of women who die suddenly have not had any previous symptoms.

![]() There was an increased need to review and develop strategies for the prevention of CHD in women following the Women’s Health Initiative and the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study.

There was an increased need to review and develop strategies for the prevention of CHD in women following the Women’s Health Initiative and the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study.

![]() The number and percentage of women participating in clinical trials has been increasing, which provides more evidence of efficacy of different treatment strategies.

The number and percentage of women participating in clinical trials has been increasing, which provides more evidence of efficacy of different treatment strategies.

![]() Because the characteristics of patients seen in clinical practice may not be similar to those of clinical trial participants, it is necessary to evaluate the ability to apply these data in practice.

Because the characteristics of patients seen in clinical practice may not be similar to those of clinical trial participants, it is necessary to evaluate the ability to apply these data in practice.

Define the Clinical Questions to Be Addressed

After the topic has been selected, the next step is to further define the specific issues for which recommendations will ultimately be provided. The guideline development group will consider what specific decision-making or action steps related to disease surveillance or screening methods for disease detection, confirmation of the diagnosis, or treatment can be improved with specific recommendations. The decision-making points can be expressed as clinical questions. ![]() The definition of the clinical questions to be addressed by a guideline is a key step that provides direction for the activities to follow. The questions are important to provide direction to the systematic review of the literature, and they also provide the outline for the recommendations that the guideline will provide. The importance of this phase cannot be overemphasized. Just as in the systematic approach to a drug information question, it is critical to first clearly define the question to be successful in searching for the necessary evidence, and subsequently be able to provide useful valid conclusions.

The definition of the clinical questions to be addressed by a guideline is a key step that provides direction for the activities to follow. The questions are important to provide direction to the systematic review of the literature, and they also provide the outline for the recommendations that the guideline will provide. The importance of this phase cannot be overemphasized. Just as in the systematic approach to a drug information question, it is critical to first clearly define the question to be successful in searching for the necessary evidence, and subsequently be able to provide useful valid conclusions.

A clear description of the questions to be addressed by the guideline is also a good starting point for a practitioner to determine if a guideline could be useful in his or her practice. Depending on the overall goals of a guideline, questions may be about the best diagnostic test, methods of screening, what forms of treatment or prevention are most effective, quantification of the potential harms of treatment, what comorbidities change recommendations, or what costs are associated with different management strategies.

One of the important steps for guideline developers, and perhaps even more important for guideline users, is the careful framing of the clinical questions. Many guideline development groups use the Patients-Interventions-Comparison-Outcomes (PICO) model for framing the questions, which includes the following parts13:

![]() Patients: Which patients are being considered for the guideline, how can they be described, and are there any subgroups that require special consideration? (similar to inclusion and exclusion criteria in a clinical study, however, usually not as restrictive)

Patients: Which patients are being considered for the guideline, how can they be described, and are there any subgroups that require special consideration? (similar to inclusion and exclusion criteria in a clinical study, however, usually not as restrictive)

![]() Interventions: Which intervention or treatment should be considered?

Interventions: Which intervention or treatment should be considered?

![]() Comparison: What other interventions or treatment should be compared with the intervention being considered?

Comparison: What other interventions or treatment should be compared with the intervention being considered?

![]() Outcome: What is most important to the patient (e.g., mortality, morbidity, treatment complications, rates of relapse, physical function, quality of life, and costs)?

Outcome: What is most important to the patient (e.g., mortality, morbidity, treatment complications, rates of relapse, physical function, quality of life, and costs)?

The clinical questions should define the relevant patient population, the management strategies that will and will not be considered, and the outcomes of care that the guideline intends to achieve. All the questions that are necessary for consideration of patient management in a given clinical scenario are delineated to make sure that the recommendations provided by the guideline will be of sufficient scope to avoid important gaps in decision making. There is no specific standard for the number of questions required for each guideline; however, most guideline development groups state that if the number exceeds 30, or in some cases 40 questions, it may be necessary to break the guideline into subtopics. Subtopics may be determined to construct a guideline for making recommendations for screening or diagnosis in one guideline and recommendations for treatment in another. Or subtopics may be based on differentiation of populations that have different levels of severity of disease, for example, New York Heart Association classes of heart failure, or based on other demographic factors that might call for different recommendations for care of those patients. The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on antithrombotic therapy created several subtopics such as antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy, persons with peripheral artery disease, ischemic stroke, valvular disease, and atrial fibrillation.

In some instances, a preliminary review of the literature may be necessary to assist with delineation of the focused clinical questions to be considered in the guideline. Clinical experts in the field as well as patients provide critical input in formulating the clinical questions.

Determine the Study Screening Selection Criteria

It is necessary to define the admissible evidence, i.e., the types of published or unpublished research to be considered so that an appropriate literature search may be performed. Key words from the focused clinical questions define the types of patients, interventions, comparators, and outcomes of studies that are considered to provide useful evidence. The guideline panel may decide that it will consider evidence from previous guidelines, meta-analyses or systematic reviews, and randomized controlled trials. The panel may also decide to consider evidence from observational studies, diagnostic studies, economic studies, and qualitative studies. This direction is necessary for the information specialists that will conduct the search for evidence. Detailed criteria are also important in this step so that evidence will be retrieved and selected for inclusion in the review with a minimum of bias, so that the search is reproducible, and so that the entire process is as transparent as possible. In most cases, more than one person is involved in searching for evidence and selecting evidence for consideration in the review. Clear criteria must be used so that there is consistency among all individuals involved in this process. Inconsistency in the retrieval of evidence between evaluators would add a potential for bias in the review.

The process to define admissible evidence may also be revisited at a later stage of guideline development depending on the results of the initial search. It is conceivable, and in fact common, that based on the initial review of evidence, the questions may be modified or new questions formed, and a decision may be made to expand the scope of admissible evidence. Documentation of these decisions, and the reasons for any changes, is another indicator of a guideline that has been developed with rigorous methods.

Conduct a Systematic Search for Evidence

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree