LEARNING OBJECTIVES

INTRODUCTION

Lucy, a 4th-year medical student, is walking down the hall with her attending surgeon, Dr. Wong, at the end of their inpatient ward rounds. Lucy tells Dr. Wong that the patient they are about to see wants to know the results of her latest tests. The patient is a few days post-liver transplant, and on a postoperative film they discovered a large lung mass that was not noticed preoperatively, and no one has told the patient. Every day the patient asks about any new test results, and Lucy feels awkward not telling her. Dr. Wong tells Lucy that it is up to the medical team and not up to them, as they are just responsible for the surgery and postoperative care. Just then, Dr. Wong gets paged away to the operating room, and Lucy enters the patient’s room on her own. The patient is in good spirits, and wants to go home soon. She asks Lucy, “What do my tests show?”(Ginsburg, Regehr, & Lingard, 2003).

What should Lucy do? Her basic options are “tell” and “don’t tell,” but clearly it is more complicated than that. Let’s assume Lucy has just been to a lecture on the importance of honesty and full disclosure with patients, and decides to “be honest” and tell the patient about the x-ray finding. What would happen next? The patient would be fully informed about her condition, which was the student’s goal—but she would also likely be terribly distraught and would have many follow-up questions. Is Lucy equipped to deal with the patient’s emotional reaction and answer all of her questions about diagnostic possibilities, prognosis, effect on her transplant recovery, and so on? How might the patient feel now, knowing that a mistake may have been made, potentially exposing her to unnecessary risk? And to make things worse, now she thinks that her other doctors were aware and hid it from her—how might that affect her trust in her doctors and the system in general?

Now let’s assume that Lucy—for whatever reason—decides to obey Dr. Wong’s directive to not tell the patient. What would happen next? Lucy would not get in trouble and eventually the patient would be told by one of the attending doctors. The patient might still be upset that people (including the student) knew and did not tell her. An attending doctor would likely be able to effectively manage the patient’s emotional reaction and would be able to answer her questions about diagnostic and prognostic possibilities and create a mutually agreeable management plan.

What does this have to do with evaluation? What if you had to evaluate Lucy, and she had decided not to tell the patient about the x-ray result? If you feel that it is wrong to withhold the truth no matter what, this failure to disclose would be considered a lapse in professionalism. But if she happened to have an evaluator who felt that sometimes it is better to withhold the truth, at least temporarily until they can get someone more experienced to do so with them, the student might receive a very good evaluation of her professionalism, because she minimized the patient’s anxiety overall. So the same behavior—essentially amounting to dishonesty—could be evaluated as either good or bad, depending on how the situation is construed by the person evaluating her (Ginsburg, Regehr, & Lingard, 2004).

This scenario is a good example of why evaluating professionalism can be so difficult. If we focus on the issue of honesty with patients, it is easy to say, “Always be honest,” but it is clearly more complicated. Simply blurting out “the truth” without consideration of people’s feelings and reactions can be just as damaging as lying. What this exemplifies is the importance of context in interpreting people’s behaviors, a point that will be expanded on again later (Ginsburg et al, 2000).

WHY IS EVALUATING PROFESSIONALISM SO DIFFICULT?

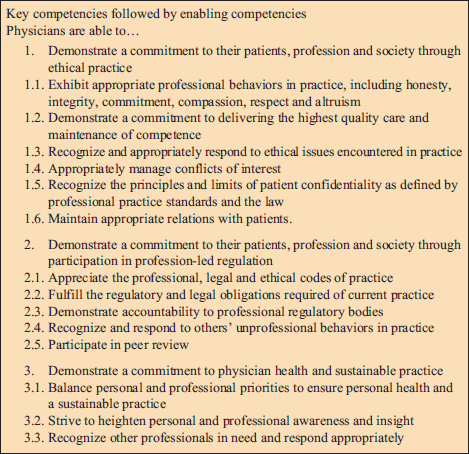

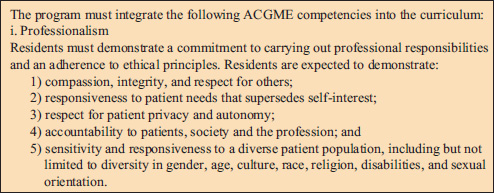

In the past, professionalism was often treated (taught, discussed, and evaluated) in a different way than other knowledge and skills, and was often not taught at all. One reason is that professionalism has traditionally been tricky to define, and if it is not clearly defined it is hard to assess when it is done well or poorly. That is why the framework presented in this book is useful in terms of operationalizing professionalism as a set of behaviors that can be observed and evaluated. There is certainly no shortage of definitions of professionalism that one can find by doing a literature search and, in general, there is consensus around the major themes (Lynch, Surdyk, & Eiser, 2004). What often differs between definitions is the emphasis and priority given to various elements, as well as the boundaries drawn around them. For example, in Canada and some countries in Europe, the CanMEDS framework is used for student and resident evaluation and includes “professional” as one of seven essential roles required of physicians (Frank, 2005). Its definition, framed as “key” and “enabling” competencies is shown below in Figure 10-1. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) framework (Figure 10-2), used in the United States, includes professionalism as one of six competencies (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2012). These frameworks were developed to guide teaching and to enable evaluation in the postgraduate setting.

Figure 10-1

CanMEDS professional role.

Credit: Frank JR. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better Care; 2005. Available at: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/resources/publications/framework_full_e.pdf. Copyright © 2005 The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds. Reproduced with permission.

The CanMEDS definition is broader than the one from the ACGME, encompassing not only the usual behaviors we consider (honesty, ethical behavior, and so on) but also a duty to participate in self-regulation (including peer review) and to attend to one’s own personal health and wellbeing. It is also evident that many of the behaviors listed involve effective communication, yet this word does not appear explicitly. That is not to imply that communication is unimportant to professionalism, only that explicit evaluation of communication is captured in other components of the CanMEDS and ACGME frameworks. Clarity about the definition of professionalism is critical before planning evaluation.

There are other reasons that evaluating professionalism can be difficult. One issue is that if one starts with abstract principles, such as “honesty,” it can be difficult to operationalize exactly what that means and how to apply it in a given situation, like in the earlier example. Often we make it seem too black and white—the student told the truth or she lied; someone is “professional” or “unprofessional”—which leaves no room for gray, for interpretation in context (Ginsburg et al, 2000). Perhaps most importantly, issues of professionalism have often been considered to be issues of character, of a person’s personality or traits—a student is “honest” or “a liar”—and not as issues of behavior. Nobody wants to judge someone else’s character as good or bad and, hence, framing professionalism as a character trait has historically been a barrier to evaluating professionalism. In fact, we mostly find that lapses in professionalism occur in basically “good” (or well-intentioned) people who are acting in difficult situations; this framing makes it much easier to evaluate without judging (see Chapter 2, Resilience in Facing Professionalism Challenges).

RELATIONSHIP OF ATTITUDES TO BEHAVIORS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EVALUATION

Dr. Reid, an attending on general surgery, is asked to complete an evaluation on Kevin, one of her residents, who she’s been working with for the past 2 weeks. Between post-call days, clinics, and other events, she realizes she has not directly observed much of Kevin’s performance. His patient assessments seem to be accurate and he is efficient in completing his work by the end of the day. He is quite good technically in the operating room (OR). She thinks he meets expectations for professionalism but is now feeling uneasy filling out this part of the form. On the one hand, she’s heard no complaints about him, and has not witnessed anything egregious. On the other hand, there was that time he seemed a bit glib and insensitive when discussing an obese patient in the surgeon’s lounge. She overheard him say it was the patient’s fault that she now requires bariatric surgery. The other surgeons in the lounge did not react at all. Dr. Reid is now, in retrospect, concerned about this potentially negative attitude, although she has no evidence it altered his care of the patient.

Why is Dr. Reid feeling uneasy? Partly because she realizes (too late) that she did not spend sufficient time directly observing this resident’s behavior, and the potential “red flag” has not been explored or addressed. But another reason is that she is not sure whether having a bad attitude toward something is really important, or whether it is the behavior that counts. She is not alone—in fact, an enormous body of research has confirmed that the link between attitudes and behaviors is tenuous. One meta-analysis of nearly 800 studies in psychology found that the relationship between a person’s attitudes and their behaviors was only moderate (with a correlation of about 0.4) (Wallace et al, 2005). When the pressure to behave in a particular way is high, or the behavior is more difficult to enact, the correlation between attitudes and behaviors may be significantly lower (Rees & Knight, 2007). Overall, evidence suggests that if the attitude is not very strong, the behavior is difficult, and there is a lot of pressure involved, the attitudes themselves may not count for much. This is actually helpful when we try to understand why “good” people sometimes do “bad” things. Indeed, putting it into the context of medical education, this is exactly the situation we see in medical students, who likely have very good attitudes and intentions to behave in certain ways but face a great deal of pressure to act otherwise; some of these behaviors can be quite difficult (e.g., going against one’s resident or attending’s directive). Yet we neglect these important influences when we evaluate, focusing solely on the individual and neglecting the context—or, if not entirely neglecting it, believing that the student should be “strong enough” or mature enough to overcome these external factors (Ginsburg, Lingard, & Regehr, 2008).

The example of Kevin who comments negatively about the obese patient demonstrates the other side of this—a resident who may have a negative attitude but does not appear to have actually done anything wrong. Since nothing bad happened to a patient, should Dr. Reid ignore the attitude? The answer, of course, is no! This situation presents an excellent teachable moment to explore what lies behind Kevin’s comment. For example, maybe Kevin was echoing what he heard from other surgeons and does not, in fact, have a negative attitude—maybe he was just trying to fit in. Alternatively, Kevin may have made a glib comment as a joke without understanding the negative impact of his comment on others, including students for whom he serves as a role model. Kevin may also have been using black humor as a cathartic way of dealing with a stressful situation, which Dr. Reid may be unaware of. To better understand Kevin’s performance, Dr. Reid should attempt to gather information from other sources (e.g., other attendings, nurses, students, and so on) to see if this is an isolated issue or if patterns exist. Just because the behavior in this case did not appear to be a problem, we do not know if it will be in the future, so looking at patterns and consistencies in behaviors is much more important than evaluating any one point in time.

EVALUATION IN THE CONTEXT OF THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

An attending, Dr. Brown, is on the wards and sees that his resident, Dr. Kessler, is struggling to order a test on the computer. Dr. Kessler’s password does not seem to be allowing her to log in and she does not have time to call information technology to get it reset. Last time it took over 20 minutes. She notices that another resident has walked away from one of the computer stations and forgot to log out, so she goes over and orders her patient’s test on the other resident’s account. She logs out and walks away.

What should Dr. Brown do? Dr. Kessler violated the hospital’s policy, which clearly states that it is forbidden to use another healthcare provider’s account for any reason. Her behavior could be considered a lapse. But Dr. Brown also realizes that the hospital’s new computer system makes it difficult at times to get things done efficiently, and they have had lots of problems with passwords lately. How should he evaluate his resident’s professionalism? If he decides to take the systems issue into account, how might that look on an evaluation form? The form only focuses on the individual.

Fortunately there is now a growing recognition of the importance of taking the bigger picture into account when evaluating professionalism. For example, an international working group on evaluating professionalism suggested that there are three main perspectives, or lenses, through which evaluation might be considered (Hodges et al, 2011).

The first perspective is that professionalism is an individual level characteristic, trait, or behavior.

The second considers professionalism as an interpersonal process (e.g., teacher-student, student-student, or student-patient).

The third, most often forgotten, is that professionalism is also a socially determined phenomenon associated with power, institutions, and society.

It is too easy to consider only one perspective (usually the individual level) and neglect the influence of the other two. It is equally important to not neglect individual responsibility when considering the effect of institutions and organizations. This is consistent with the framework used in this book that highlights the influences of teams, settings, and the external environment on professionalism in daily life.

For the preceding case, where the resident used another healthcare provider’s computer access, we can see that although the resident did something incorrect, there were other issues involved: the challenging computer system, poor IT support, the other resident’s failure to log out of his session, and perhaps a lack of other knowledge or resources that would have enabled her to behave more appropriately.

Despite recent advances, most of our evaluations of professionalism are still focused on individuals, largely for the practical reason that we need to ensure that individuals are able to behave professionally. In the past these evaluations would often involve an assessment of attitudes, but we have shifted significantly over the years to more of a focus on behaviors. As described earlier and elsewhere in this book, this is in part due to the recognition that attitudes are not very good predictors of behavior. It has also been argued that behaviors may be easier and more “objective” to evaluate, yet we have also seen (as in the first example of honesty with the patient) that a particular behavior may be judged differently by two different people, depending on what they think the underlying motivation was behind it (Ginsburg, Regehr, & Lingard, 2004). Some studies have found that the evaluator’s opinion about the motivation may outweigh their opinion about the behavior itself. If we ascribe a behavior to what we think of as a “good” intention, we will think of the behavior as “good,” and vice versa. But of course we usually don’t know what the intention is, and instead we infer it.

You might think that if we knew people’s intentions we would be much better positioned to judge their behavior. However, in reality it is difficult for people to decide what is more important—the behavior or the motivation behind it (Ginsburg, Regehr, & Mylopoulos, 2009). What is better—a student who does the wrong thing but for the right reason or a student who does the right thing for the wrong reason? As Hafferty (2006)asked, “Do we want physicians who are professional, or will we settle for physicians who can act in a professional manner?” A patient may greatly prefer the “right” behavior to be done, but from an education and development perspective it may be more important to focus on the students’ reasons for action, as then we can form a basis for education (Rees & Knight, 2008).

It might seem strange to be critical of evaluating behaviors when our framework emphasizes them. Yet the two points of view are not contradictory—we advocate for assessing behaviors in context. Perhaps even more importantly, the patterns and consistencies in behavior are far more important than one-off events, however,good or bad they may be. In the case of Dr. Kessler, the resident who used someone else’s computer password, the attending decided to have a conversation with her about this apparently common workaround. Dr. Brown had known Dr. Kessler for 3 weeks and had never witnessed problematic behavior, so this appeared to be a one-off event rather than partof a pattern. Although Dr. Kessler recognized that it was against the rules, it turns outthat many others use the same strategy. Instead of recording a lapse in professionalism, Dr. Brown realized that what was more important in this situation was that Dr. Kessler learns better strategies for the future (e.g., being a bit more patient and waiting her turn, politely asking someone if she could use an occupied computer, using one on another nursing station, and so on). Together, they decided to approach the IT department and help come up with a solution to the problem so that the workarounds would no longer be necessary.

LEARNING EXERCISE 10-1

Think of an incident in which a student, resident, or physician displayed potentially unprofessional behavior.

Can you describe the responses, both verbal and nonverbal, of all who were present (including yourself)?

Do you think the responses were appropriate? Explain why or why not?

Was this behavior documented on an evaluation? Why or why not?

Would you do anything differently if it happened again?

INSTRUMENTS FOR MEASURING PROFESSIONALISM

A comprehensive analysis of all possible methods for evaluating professionalism is clearly beyond the scope of a single chapter. Luckily, several excellent resources exist for this purpose (Lynch, Surdyk, & Eiser, 2004; Stern, 2006; Goldie, 2013). No one instrument will be capable of evaluating every element of professionalism in all possible contexts and for multiple purposes. Thus a system of evaluation is critically important, one that includes multiple methods with varying strengths and weaknesses and importantly integrates them into a holistic assessment of an individual’s competence (Schuwirth & van der Vleuten, 2012). If we remember that professionalism can be thought of as a multidimensional competency that evolves over the course of a persons’ education, training, and professional career, we can start to imagine what good evaluations might look like along the way.

First, it is important to consider the purpose of assessment. There are many reasons to evaluate people, including:

a need to ensure competence for practice (or for the next stage of learning);

to plan remediation;

to feedback to curriculum if systematic gaps are found; and

for medical licensure.

But more recently there has been a recognition that assessment is not only of learning but for learning (Schuwirth & van der Vleuten, 2011). Assessment in and of itself is a learning experience. Usually we think of assessment as being either formative or summative (formative refers to assessment that does not “count” and is for feedback purposes only; summative counts for decision-making). Figure 10-3 depicts the components that evaluations should encompass.

Thus we should be thinking about systems of assessment rather than of individual tools (van der Vleuten & Schuwirth, 2005). Given the developmental nature of professionalism as a competency, it is also important to use different methods for different stages. Figure 10-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree