Evaluating a Portfolio of Investigational Drug Projects

Trying to assess basic research by its practicality is like trying to judge Mozart by how much money the Salzburg Festival brings in each year.

–Konrad Lorenz, Austrian naturalist.

OBJECTIVES AND PERSPECTIVES OF A PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS

What Does Portfolio Analysis Mean?

The term portfolio analysis is used to describe an examination of a group of compounds and/or drugs using medical, scientific, commercial, financial, and/or other parameters. Drugs that are evaluated may be (a) investigational, (b) marketed, (c) a combination, or (d) focus on any subset of those groups (e.g., the ten most important projects in terms of commercial value or staff effort). The analysis of any parameter may vary from a subjective appraisal to a precise quantitative evaluation using standard financial or other methods.

A portfolio analysis may be conducted as a special one-time exercise or as part of an annual or other periodic review. If the analysis is conducted as a special one-time exercise, there is a greater likelihood that it will be performed (in whole or in part) by outside consultants rather than by internal company staff.

The analysis may be limited to assessing medical and commercial values, or it may include other aspects as well. Although there is substantial information to be obtained from analyzing the previous year or half-year, the most important information usually comes from comparing results with those obtained on several past occasions. This allows trends to be identified and may raise issues that should be addressed. An analysis will have value if (a) the information used is valid, (b) the information used is current, (c) appropriate methods are used to conduct the analysis, and (d) a sufficient effort is expended on the exercise.

What Are the Purposes of a Portfolio Analysis?

The purpose(s) of the portfolio analysis must be defined in advance of the exercise. A portfolio analysis may be used to provide characteristics of the therapeutic areas and even an understanding of the businesses the company is in. A company may thus evaluate whether the characteristics of the therapeutic areas being researched and targeted with new projects match its expectations. The analysis may also be used to demonstrate whether the company is actively engaged in businesses that provide long-term growth opportunities. Another purpose may be to identify potential gaps in the portfolio over various periods of time when new products are not expected to be launched.

A portfolio analysis may also be used to decide which projects should be retained and which should be pruned. If the analysis is not limited to looking at each project as an overall entity, but examines each of the indications, dosage forms, and routes of administration separately, then it is possible to evaluate which of those aspects should be retained and which should be pruned. Projects may be pruned or temporarily allotted minimal resources to reallocate finite resources to higher priority projects.

Pruning projects from a portfolio does not necessarily mean that the projects clipped are to be terminated. Another possibility is that pruned projects may be licensed-out or used as trading material (as a quid pro quo) for cross-licensing with another company. If drug discovery becomes less fruitful for a company, it will have a much stronger motivation to increase licensing-out of its pruned projects or even pruned dosage forms. An intermediate step is to diminish resources allocated to a project so that it barely remains alive or progresses at a minimal pace.

Lowest Common Denominator

The principal focus of thinking about a portfolio is in terms of the individual project. It is, nonetheless, insufficient to focus solely on projects as the lowest common denominator in analyzing a portfolio. Each indication, dosage form, route of administration, and dosing regimen studied should be evaluated independently in terms of its medical and commercial importance. Resources applied to their development should be appropriate, both in terms of quantity and also in terms of timing. For example, it may be appropriate to ask if development of some indications of a drug should be delayed. Each of several indications pursued in a large project may utilize the same quantity of resources allocated to the sum of five (or even more) small projects. Only through a thorough analysis of a project’s individual parts can the value of the overall project be adequately ascertained.

When discussing secondary indications of a drug, it is relevant to consider whether they are spin-offs and closely related to the primary indication or whether they are in different therapeutic areas. An indication that was originally secondary in importance may become the primary one for a drug in medical and/or commercial terms. As the number of indications being evaluated increases, it is essential to determine whether a fixed quantity of resources is being divided into smaller pieces or whether there is an incremental growth in resources. The answer to this question should have a significant impact on the strategy developed for each project.

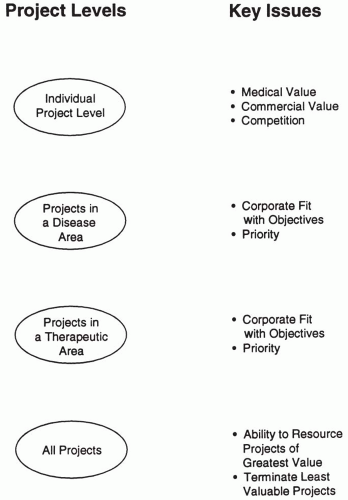

Levels of Projects

In conceptualizing the portfolio exercise, it is useful to think in terms of levels of projects. This is shown in Fig. 52.1. as four levels: (a) individual projects, (b) projects in a disease area, (c) projects in a therapeutic area, and (d) all projects. The various issues, questions, and problems associated with the portfolio can then be associated with the appropriate project level. For example, when individual data are being collected and reviewed for a single project within a given therapeutic area in the portfolio, it usually is premature to question whether the entire therapeutic area should be eliminated (or resourced at a greater level). The four levels of conceptualizing projects also provide a basis on which to organize the first steps of the portfolio analysis.

Portfolio Gaps

Numerous types of gaps may exist in a portfolio. For these to be adequately addressed, they must first be identified by type (see below). Each of these gaps is based on the company not achieving its goals. Goals must be identified prior to determining that a gap is actually present or is projected to occur sometime in the future.

Gaps in research activities. Inadequate drug discovery activities are being conducted in therapeutic areas of importance to the company. Alternatively, research may be ongoing in areas of interest, but research goals may not be met.

Gaps in discovering novel compounds of importance. An inadequate number of important chemical leads have emerged from research that have entered the drug development system (i.e., project system). The company is therefore not meeting its drug discovery goals.

Gaps in developing compounds of importance. Inadequate or no projects are active in the drug development pipeline in certain therapeutic areas. Alternatively, no projects are active in specific phases of development, or other drug development goals (e.g., number of projects in the system) are not being met.

Gaps in submitting New Drug Applications (NDAs). Research and development is not meeting its goals of submitting X number of NDAs per year of new chemical entities (NCEs) and Y number of supplemental NDAs for line extensions.

Gaps in financial forecasts. Products to be marketed plus current products are not expected to meet the company’s financial goals.

Gaps in licensing activities. Goals set for licensing activities to fill any of the above noted gaps are not being met.

Gaps in marketed drugs. Various types of gaps may exist in specific therapeutic or disease areas.

Portfolio gaps resulting from lack of new products could also be viewed in terms of potential financial shortfalls over a specific number of future years. If short-term gaps are identified (i.e., within a four- or five-year period), an attempt may be made to fill them through (a) acquisition of new products, (b) acquisition of another company, (c) corporate merger, (d) licensing-in of marketed and/or investigational drugs, or (e) rapid development of line extensions. Long-term gaps (e.g., greater than a five-year period) could be addressed through changes in basic research, proactive licensing, joint ventures, or acquisition of other companies.

Perspectives of Various Groups Conducting a Portfolio Analysis

The group conducting a portfolio evaluation may be based in research, marketing, finance, or another section of a company. Their approach, methodologies, and orientation will undoubtedly be affected by their training and the purposes of the review. Any of these groups could conduct the entire portfolio exercise without soliciting help from other groups. This means that the medical value may be assessed by marketing personnel and the financial value by research personnel, but this approach would generally yield data that would be less believable to most reviewers and corporate officers than if the analyses are conducted by those who are most expert in that field. If asking help from other groups creates a problem (e.g., too much time required), then a team appointed by the Chief Executive Officer or a nonpartisan person or group may be chosen to conduct and direct the entire exercise. This may require the services of an outside consultant who has the requisite capability and credibility. Another alternative is to have internal staff generate the report and to have either staff at a separate company site or a consulting group audit and review the results.

An important part of the perspective used in approaching portfolio analysis includes consideration of (a) which pharmaceutical businesses (e.g., prescription, over-the-counter drugs, generics, and biotechnology) will be considered; (b) the scope of projects, drugs, and/or research compounds to be considered; (c) which geographical area is being considered (e.g., single country, single development site, single company, or worldwide operations); (d) who is to conduct the analysis; and (e) who will make decisions about questions that arise. Separate portfolio analyses could be conducted on marketed drugs, investigational drugs, and research compounds. Other types of portfolios are described in the next section.

Reviewing a Multinational Company’s Overall Portfolio and Those of Individual Sites

Multinational pharmaceutical companies often conduct research and develop drugs in two or more countries simultaneously. Each of the major sites for these activities may have relative autonomy and independence, although their efforts are coordinated to some degree with the other sites. In this situation, the portfolio of one country’s projects will undoubtedly overlap with that of other sites. In addition to the portfolios of the individual sites, the portfolio of the company as a whole should be analyzed. Comparisons may be made between these site-specific portfolios as well as comparing portfolios with industry averages. Managing directors within each country where a company’s drugs are sold may also conduct portfolio analyses.

Even if portfolios of two separate sites developing drugs for the same company contained the exact same projects, the commercial value of each portfolio would probably be completely different. Imagine that one site was developing drugs for the American market and the other site was developing the same drugs for the rest of the world. The commercial value of drugs being developed to treat tropical diseases would clearly differ between the two sites. The value of drugs for many other diseases would also differ markedly between sites because of other factors. These factors include (a) the status of existing and projected competition, (b) the way that medicine is practiced in different countries (e.g., whether certain types of drugs are or are not commonly used), (c) the size of the pharmaceutical market(s), (d) the ability of each site to sell the drug, and (e) numerous other factors.

DEVELOPING A PORTFOLIO

Determining an Ideal Portfolio

There may be occasions in reviewing the company portfolio, evaluating the portfolio of another company, or planning in which direction to develop a company’s portfolio when it is important to consider what the ideal drug portfolio would look like.

A portfolio of prescription drugs under development may be viewed as consisting of three separate types of investigational drugs: (a) innovative NCE drugs, (b) “me-too” NCE drugs, and

(c) line extensions. The ideal portfolio, according to the director of research, may differ from that defined by the director of marketing or the director of production. Therefore, there is no single concept of an ideal portfolio, except possibly in the most general terms.

(c) line extensions. The ideal portfolio, according to the director of research, may differ from that defined by the director of marketing or the director of production. Therefore, there is no single concept of an ideal portfolio, except possibly in the most general terms.

Determining a Realistic Portfolio

Factors that must be considered in choosing new compounds or drugs to include in a portfolio are as follows:

Patent life remaining at the time of a drug’s launch. This estimated period should be adequate to recoup development costs and to make a profit. Exceptions may be included if agreed to by relevant managers.

Regulations. Regulations that must be followed to have drugs developed and approved must be attainable.

Time to develop and market drugs. This time should be near the lower end of the average range, insofar as possible. Drugs vary greatly in this regard, so a more reasonable goal might be to have a mix of short-, mid-, and long-term projects.

Costs to develop and market drugs. Projected costs should be reasonable, unless the anticipated return on investment justifies larger development costs. Spending huge sums to develop an orphan drug is rarely realistic.

Social attitudes about drugs. These should be positive or neutral. If problems are anticipated, then an educational campaign or another approach should be considered. If this is not feasible or would not be cost effective, then the drug’s development plan should be reassessed.

Clinical feasibility. Drugs should be possible to study in terms of patient availability and clinical parameters to measure. It may be possible or even necessary to utilize new efficacy parameters to evaluate a drug, but the credibility of such parameters to the Food and Drug Administration and prescribing physicians must be assessed.

Medical value. This should be high, although it cannot be accurately established for most investigational drugs until after a number of patients have been studied.

Commercial value. The portfolio’s overall value should be appropriate from the perspective of meeting the company’s financial goals. Financial goals should allow room for a limited number of less commercially attractive drugs to be included in the portfolio when they contribute high medical value and have a high likelihood of being marketed.

Probability of achieving marketing. This should be high for most drugs in the portfolio. Long shots from a medical efficacy or safety perspective should generally have high commercial value if a decision is made to develop the drug.

Legal considerations. There should not be significant legal issues (e.g., probability of product liability suits) or social issues (e.g., potential for drug abuse) for most, if not all, drug portfolios. Oral contraceptives are a group of drugs where numerous social issues have been raised (e.g., use in underdeveloped countries and religious sanctions), as well as a major issue in terms of benefit-to-risk considerations, which have changed over the past 25 years.

Competitive value. Two aspects of competitive value should be considered. First, most, if not all, drugs in the portfolio should offer a real advantage over existing drug therapy. This advantage may be in terms of an improved benefit-to-risk ratio or another advantage such as improved absorption, quality of life, convenience, compliance, or acceptability to patients. If the drug will compete with one of the company’s own products, competition may enhance sales or lead to severe cannibalization of the marketed drug’s sales. Second, the number of competitors present in the therapeutic areas where drugs are being developed should be determined, and the potential impact of the competitors should be assessed. Assessments should be in terms of expected time to market, as well as important advantages and disadvantages of the competitor’s drugs in comparison with the company’s drug.

ANALYZING THE VALUE OF A PORTFOLIO

Comparison of Scientific versus Medical Value

There is an overlap between the parameters used to assess the scientific and medical value of a portfolio. Medical value refers to the actual ability of the new drug to address the Medical need (i.e., Public Health need) for a new treatment and includes consideration of the direct benefits it will provide to patients and the indirect benefits it will provide to healthcare providers. Scientific value relates to the interest in a new drug from an academic and research perspective. This includes consideration of the drug’s scientific novelty and mechanism of action. Drugs with high scientific and low medical value are described in Chapter 49 as “sexy drugs.” Few new drugs have high medical and low scientific interest because the mechanism of how an important new drug works would usually be of great interest to academic scientists, if not practicing physicians. Nonetheless, one possible example of a drug that has high medical and low scientific value was the discovery that mannitol was an important new treatment for brain edema through its production of an osmotic diuresis. The mechanism of this effect was believed to be known, and there was relatively little scientific interest generated by this important medical discovery. “Me-too” drugs are in a different category because they have little scientific and little medical value but may achieve significant commercial success.

Judging the Scientific Value of a New Drug

The scientific value of individual drugs may best be gauged on a relative scale from low to high. Determining where a drug fits on this scale is usually straightforward and noncontroversial. As a drug’s medical value changes, there is often, but not always, a concomitant change in its scientific value. The scientific value is based to a large degree on the scientific novelty of a drug’s mechanism of action and the chemical novelty of its structure. Drugs that are unique in the way they act have a high scientific value, but unless they have desirable clinical properties, their medical value may be low. A drug that is found to be toxic and is withdrawn from the market (i.e., loses its medical value) may retain its scientific value and interest if it is the only known drug to stimulate or inhibit a receptor or target of interest or has another property of interest.

Drugs with high scientific value may be marketed in part on that basis. Marketing claims may state that Drug X is the first of a new type of drug to treat disease D, that Drug X is the only commercially available drug to inhibit the Y receptor, or that Drug X is the first drug to stimulate enzyme Z. Whether the latter two

claims are accompanied by desirable clinical effects or remain merely pharmacological activities must be assessed by the physicians who read these or related claims.

claims are accompanied by desirable clinical effects or remain merely pharmacological activities must be assessed by the physicians who read these or related claims.

Rating the Medical Value of a New Drug

The medical value in terms of the benefit to patients and the practice of medicine may be most easily described for each project in the portfolio according to one or more simple scales. Examples of such scales include the following.

The drug has high, moderate, or low medical value (based on a subjective assessment, questionnaire, or other method). This assessment is made with a 3-point scale.

The drug has extremely high, high, moderate, adequate, little, or no medical value. This is a 6-point scale.

The benefits of the drug are expected to reach: over ten million patients per year, over a million patients per year, over ten thousand patients per year, or another number of patients per year. These numbers may be estimated by marketing groups using input from research and development about the drug’s characteristics.

The drug is viewed as providing life-saving therapy, relief of a debilitating disease, high or moderate relief of a chronic disease, or high or moderate relief of an acute disease.

The percentage of all patients with the target disease who are expected to use the drug is: 75% to 100%, 50% to 75%, 25% to 50%, or 0% to 25%.

The overall medical benefits of the drug may be rated by a group using an arbitrary scale of one to 100.

The ability of the drug to displace current therapy for a disease.

The likelihood of physicians prescribing the drug for their patients.

Almost all of these scales assess a drug’s medical value relative to existing drug and nondrug therapy. Only Scale 4 can be rated independently of existing therapy.

Another method of determining the medical value of a drug is to compare the therapeutic ratio of a drug with those of existing drugs. The therapeutic ratio equals the dose that causes adverse events divided by the dose that causes a beneficial effect. The larger the number is, the safer the drug is. This approach would only be practical for drugs that have completed Phase 2. Prior to that point, it would be impossible to assess a drug’s therapeutic ratio. The therapeutic ratio of some drugs entering Phase 3 studies is still difficult (or impossible) to determine accurately.

What Is the Therapeutic Utility of a New Drug?

The therapeutic utility of a new drug depends on the perspective of the group that is asking the question as follows:

To a pharmaceutical company. How do perceived medical benefits compare with perceived commercial benefits? Do benefits sufficiently outweigh risks so that the drug will be able to be marketed broadly?

To a regulatory agency. Can the benefits of a new drug be demonstrated in an adequate population of patients? The benefits and risks are considered on a level of the entire society (i.e., for all patients who may use the drug).

To a physician. How will the physician’s ability to treat patients be affected? The answer is usually phrased in general terms.

To an individual patient. Will the treatment diminish the intensity of symptoms, improve chances for a longer life, and/or provide a better quality of life than was available with prior therapy? The risks and benefits are considered strictly for the single patient affected. The direct effects of a drug on a patient may lead to indirect effects on others (e.g., family, friends, caregivers, and business associates).

Forecasting the Commercial Value of a New Drug

There is no doubt that the commercial value is usually the most important parameter at pharmaceutical companies for judging individual projects, as well as the overall portfolio. The commercial value of a particular investigational drug project (or the overall portfolio) may be expressed in many ways but is always based to some degree on numerous unknown factors. It may be expressed as a forecast of:

Third-year (or other) sales of the drug after it is marketed

Total sales for first three (or other) years on the market discounted to its present value

The estimated range of sales for third-year (or other) sales

The net profit after taxes for the first five (or other) years on the market

The number of years to pay off the research and development costs from the stream of net earnings after taxes

The third-year (or other) sales times the probability of success. This is a risk-adjusted forecast

The above forecast may be based on whether the drug achieves an optimistic profile, expected profile, or minimally acceptable profile. Alternatively, multiple forecasts may be given for each drug.

It is essential that all project forecasts in a portfolio be made using the same approach for all projects. This can usually be best accomplished by a single person or group that evaluates all projects. Any of the forecasts listed may be compared with opportunity costs of using the money invested in research and development in other ways.

New product forecasting is an inexact science that is subject to many changes in the market as well as changes in a drug’s profile. Most of these changes cannot be accurately defined or predicted early in an investigational drug’s development. In some situations, the number of patients to be treated after the drug is marketed is extremely difficult to estimate, and any forecast may be highly inaccurate. This situation may occur when a new drug is to be used for an as yet untreatable disease. Each year that most drugs are on the market, it generally becomes easier to forecast their sales with greater accuracy.

There is usually pressure for marketing groups to provide a forecast early in a project’s life. Providing a range of numbers based on whether a drug attains either the realistic or minimally acceptable profile is desirable. This range allows others to determine whether the minimally acceptable profile would affect the expected sales (based on the projected profile) by up to 10% or by tenfold. A range also allows others to understand the degree of variability and confidence placed in the numbers provided by those who developed them. If marketing reports estimate third-year sales of $40 million for the expected drug profile, it is uncertain whether their calculations are ±10% or ±100%. Even if a range is provided as a forecast using the expected drug profile,

it is uncertain how the minimally acceptable drug profile would affect the forecast. Marketing forecasters must be cautious about clinicians who provide them with overly positive attributes about the drug and glorify the compound’s profile.

it is uncertain how the minimally acceptable drug profile would affect the forecast. Marketing forecasters must be cautious about clinicians who provide them with overly positive attributes about the drug and glorify the compound’s profile.

ANALYZING A PROJECT PORTFOLIO IN FIVE STEPS

Steps to Follow

The first step in evaluating a portfolio of investigational and/or marketed drugs is to determine which projects should be considered as part of the portfolio. The second step in evaluating a portfolio is to evaluate each project in terms of its individual characteristics. The third step is to evaluate the overall balance and composition of the portfolio using the methods desired. The fourth step is to interpret the results. This interpretation is based on changes, trends, progress toward goals, and various comparisons. The last step is to determine if it is necessary to modify any aspects of the company or results to modify the company or business area.

Projects to Include in a Portfolio (Step One)

Categories of the portfolio include (a) marketed drugs, (b) investigational drugs, (c) drugs that are both marketed and investigational, (d) investigational drugs that have passed their go-no go decision point and are definitely going to be developed, and (e) research compounds. Other categories could also be defined.

The current phase of development or status may be illustrated for each project in the portfolio in several ways. A common method is to use a horizontal bar for each project listed along the left margin (ordinate) to show whether it is currently pre-Investigational New Drug Application (IND); in Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3 (pre-NDA submission), or Phase 3 (post-NDA submission); or is marketed. Another method is to have years along the abscissa (X axis) and to show dates of regulatory submission and approval for each project. Many alternative categorizations may be used, depending on the make-up of the drugs in the portfolio.

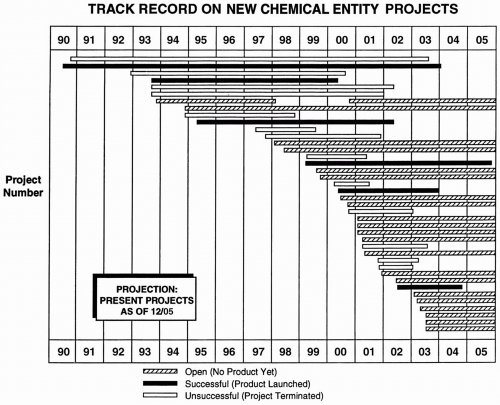

The total number of projects or drugs in the portfolio can be easily illustrated on a year-by-year basis with a line graph or histogram. This type of graph may also show the number of projects terminated per year. The number of projects initiated may be (a) expressed as a number per year, (b) compared with a standard goal, or (c) described on a moving multiyear average (Fig. 52.2A). A graph of all projects may be shown (Fig. 52.3).

Measuring Individual Projects in a Portfolio (Step Two)

Some of the parameters that may be applied to the measurement of individual projects are described in the following text. Not all of these are usually used in an analysis.

Probability of submitting an NDA, Product License Application, or other regulatory submission. Minimally acceptable standards for which a regulatory application will be submitted should be established for each drug. Based on the drug achieving these standards, a probability may then be established for submitting each project in the portfolio. This probability provides a useful single number that estimates the likelihood of marketing each drug. The major disadvantage of this measure is that it is often directly related to a drug’s phase of development (i.e., drugs in Phase 1 usually have a low probability of being marketed, those in Phase 2 have a higher probability, and those in Phase 3 have the highest probability). The probability may be assessed as quartiles (i.e., 0% to 25%, 25% to 50%, 50% to 75%, and 75% to 100%), as deciles (i.e., in tenths), or even on a scale from one to 100. The 100-point scale is clearly too detailed because small differences would not be either accurate or meaningful. If a drug’s profile becomes tarnished, it is worthwhile establishing at what point a regulatory submission would not be submitted.

Probability of achieving clinical goals. This probability is assessed in terms of safety, efficacy, and other important targets (e.g., pharmacokinetics or quality of life). This point and Point 3 listed below are subsets of Point 1 and may be expressed numerically in any of the ways discussed under Point 1.

Probability of achieving technical goals. This probability relates to issues of formulation, chemical scaleup, stability on storage, and numerous other considerations mentioned in Chapter 107. The goals are usually expressed as the minimally acceptable standards that allow continuation of a drug project. The rating of the technical attractiveness of a project may be based on answering one of several questions. What is the probability of:

Getting the product to the market

Supporting existing business

Getting to Phase 3 (i.e., passing the go-no-go decision point at the end of Phase 2)

Getting to Phase 2 (i.e., passing Phase 1)

Number of staff. Is the number of staff working on each project sufficient? This question may be assessed in purely subjective or objective terms. An objective assessment is shown in Fig. 52.2B, where a balance is sought between staff allocated and the potential value of the drug. Several other scales that could be used are also indicated in Fig. 52.2B, such as the percentage of total staff or the percentage of anticipated sales to come from current investigational drugs. The percentage of staff could refer to all development staff, total staff working on projects, senior staff, medical staff, or any other defined group. Cumulative scientist or clinician years of effort expended could be plotted for each project, for highversus low-priority projects, or for projected versus actual values.

Another aspect of staffing could be graphed as the number of people needed per project versus the number available per project. The best means of graphing this comparison might be as two vertical bar histograms per project plotted alongside each other. This approach would enable a rapid evaluation to be made for each project.

Market attractiveness (i.e., value) of the project. Each project should be commercially attractive to the company, or else there should be some other compelling reason to develop the drug (e.g., an orphan drug may enhance the company’s prestige and also enable patients to be helped who previously had no effective treatment). Various scales may be used to measure market value. These include (a) third-year (or other) sales forecast, (b) total of first three years’ forecasted sales discounted to present value, or (c) broad ranges of third-year sales. An example of the ranges could be (a) up to $50 million, (b) $50 to $250 million, (c) $250 to $500 million, and (d) above $500 million per year. The percentage of current projects in each range may be determined.

Figure 52.3 Presentation of all projects in a portfolio over time with the outcome of each project shown. The projects are listed by number and name on the ordinate. Many variations of this table are possible. For example, the definition of success could be said to be NDA submission.

Many marketers prefer a single number to indicate a project’s value to a range of values. Their reasoning is that a single number minimizes the confusion that may occur in determining where in the range the project actually lies. The profit of a drug may also be measured in numerous ways as follows: (a) specific amounts of money, (b) profits of a drug in the third year (or fifth year) after marketing, (c) the number of years until the project begins to make a profit, and (d) the total profits on a drug.

Commercial attractiveness may be rated based on the drug achieving its minimally acceptable profile for each specific indication or overall. It may also be rated based on the drug achieving the desired (or realistic or ideal) profile for each specific indication or overall. The first measure is much more useful in making decisions about the drug (e.g., Should we market the drug if it only achieves the minimally acceptable profile? If the answer is no, then the minimally acceptable standards must be increased until the answer is yes). Caveats may be used to rate commercial attractiveness (e.g., this is the commercial value if the drug is approved by 2010, and the value decreases by X percent or Y amount of money if approval occurs two years later).

Medical attractiveness (i.e., value) of the project. Each project is evaluated as to its medical importance. This can be described using several systems that are discussed elsewhere in this book.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree