Chapter Eleven

Ethical Aspects of Drug Information Practice

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Explain characteristics that differentiate an ethical deliberation from other types of decision making.

• Interpret and make use of ethics rules, principles, and theories to analyze identified ethical dilemmas.

• Identify and analyze examples of ethical dilemmas that may arise for health professionals when providing drug information, in various practice settings and for various types of clients and circumstances.

• Identify micro, meso, and macro levels of ethical decision making that may occur during the provision of drug information.

• Use the described process of ethical analysis in order to propose and justify a specific decision or course of action in an ethical dilemma case.

• Describe resources and structures that can prepare, guide, and support clinicians faced with ethical dilemmas during the course of providing drug information.

![]()

Key Concepts

What Is Ethics and What Is Not

The Ethics Course Content Committee of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) described ethics as “the philosophical inquiry of the moral dimensions of human conduct.”1 They mentioned that Aristotle taught ethics as “an eminently practical discipline” … dealing…“with concrete judgments in situations in which action must be taken despite uncertainty.”1 These authors indicated that the term ethical is often used synonymously with the term moral to describe an action or decision as good or right. They further stated that ethics is not the study of moral development, and it is not the law.

Veatch stated that “an ethical, or moral, issue involves judgments between right and wrong human conduct or praiseworthy and blameworthy human character.”2 This author indicated that an ![]() ethical deliberation may be differentiated from other endeavors by three characteristics: (1) it is ultimate or fundamental, there is no higher standard against which to measure the rightness of the decision or action; (2) the issue is universal, the parties involved in the dilemma do not consider it simply a difference of opinion or taste—each party believes there is a right or wrong answer—even if they disagree about what the answer is; and (3) the deliberation takes into account the welfare of all involved or affected by the judgment at hand. Those who provide drug information (DI) typically rely on an intuitive sense of these characteristics: we have the feeling that the situation we are confronting is a big deal, and somehow anticipate that we should not address only personal preference in the matter at hand.

ethical deliberation may be differentiated from other endeavors by three characteristics: (1) it is ultimate or fundamental, there is no higher standard against which to measure the rightness of the decision or action; (2) the issue is universal, the parties involved in the dilemma do not consider it simply a difference of opinion or taste—each party believes there is a right or wrong answer—even if they disagree about what the answer is; and (3) the deliberation takes into account the welfare of all involved or affected by the judgment at hand. Those who provide drug information (DI) typically rely on an intuitive sense of these characteristics: we have the feeling that the situation we are confronting is a big deal, and somehow anticipate that we should not address only personal preference in the matter at hand.

Over the past two decades evolving literature has described that ![]() ethical judgments may occur at micro, meso, or macro levels of health care decision making3–15: (1) a traditionally recognized micro level of health care–related decision making involves decisions made at the individual professional–patient level of health care; (2) a less commonly discussed meso level of decision making (with some literature using the term organizational for similar purpose) is variably described as occurring at the institutional/organizational level or at community/regional levels; and (3) macro level decision making often sets policy for the health system, as a standard established for an entire profession, or through government as law/regulation for the society as a whole.

ethical judgments may occur at micro, meso, or macro levels of health care decision making3–15: (1) a traditionally recognized micro level of health care–related decision making involves decisions made at the individual professional–patient level of health care; (2) a less commonly discussed meso level of decision making (with some literature using the term organizational for similar purpose) is variably described as occurring at the institutional/organizational level or at community/regional levels; and (3) macro level decision making often sets policy for the health system, as a standard established for an entire profession, or through government as law/regulation for the society as a whole.

Health care providers may be involved in ethical decision making at each of these levels related to the provision of or access to drug information. Primarily, micro level ethical decision-making scenarios will be presented in this chapter. However, certain scenarios involving meso and macro level ethical decision making will also be addressed. For example, a physician, nurse, and pharmacist may all be participating on a pharmacy and therapeutics committee that is developing an organizational policy regarding use of pharmaceutical samples within hospital clinics, or in a large independent clinic practice. The policy also addresses use of in-house professionals versus industry detailers to provide information about new drug products. Each of these professionals may have competing priorities and concerns that add ethical dimensions to their decision making on this proposed policy.11 This constitutes a meso level of ethical decision making for these professionals. A clinician participating on a national task force charged with developing policy related to medication therapy management services (with inherent drug information access) as part of a health care reform model will have macro level ethical decisions to make relative to balancing patient needs, professional identity, and societal economic constraints.10

![]() Professional ethics is different than the law. Law might be defined as rules of conduct imposed by society on its members. By contrast, professional ethics has been defined as “rules of conduct or standards by which a particular group in society regulates its actions and sets standards for its members.”16 Both constitute macro level policy making, across society or across an entire profession. Law involves written rules set by the whole society (or its representatives) that address responsibilities of that society’s members. Professional ethics focuses on explicit or implicit rules and standards set by a professional subgroup of society, and addresses the responsibilities of only those who are members of that subgroup. Certain ethical standards of a given profession may be institutionalized as law by society as a whole. However, professional ethical standards (for example, do no harm or preserve life) are often impossible to fully regulate by law. Meeting an ethical standard also goes beyond legal requirements; indeed, our ethical beliefs may on occasion command our civil disobedience (e.g., a prison pharmacist who refuses to dispense drugs to be used in legal executions). On the other hand, as will be discussed further below, law also represents one aspect of the culture within which ethical decisions are made. In considering the cultural perspectives of a given dilemma, relevant legal requirements must be identified and considered when one seeks to make an ethical decision.

Professional ethics is different than the law. Law might be defined as rules of conduct imposed by society on its members. By contrast, professional ethics has been defined as “rules of conduct or standards by which a particular group in society regulates its actions and sets standards for its members.”16 Both constitute macro level policy making, across society or across an entire profession. Law involves written rules set by the whole society (or its representatives) that address responsibilities of that society’s members. Professional ethics focuses on explicit or implicit rules and standards set by a professional subgroup of society, and addresses the responsibilities of only those who are members of that subgroup. Certain ethical standards of a given profession may be institutionalized as law by society as a whole. However, professional ethical standards (for example, do no harm or preserve life) are often impossible to fully regulate by law. Meeting an ethical standard also goes beyond legal requirements; indeed, our ethical beliefs may on occasion command our civil disobedience (e.g., a prison pharmacist who refuses to dispense drugs to be used in legal executions). On the other hand, as will be discussed further below, law also represents one aspect of the culture within which ethical decisions are made. In considering the cultural perspectives of a given dilemma, relevant legal requirements must be identified and considered when one seeks to make an ethical decision.

Ethical Dilemmas When Providing Drug Information

This chapter presents case scenarios representing ethical dilemmas. These scenarios will be utilized to demonstrate a specific method for analyzing ethical dilemmas confronted by health professionals providing drug information. The discussion will address ethical dilemmas encountered by generalist and specialist patient care providers providing drug information, as well as examples drawn from the experiences of drug information specialists. All health professionals provide drug information and must address the ethical dilemmas that arise in the course of providing this service. Many of these scenarios represent examples of micro level ethical dilemmas that primarily involve an interaction between a drug information provider and the direct recipient of the information. Other scenarios where health professionals may be providing or determining access to drug information occur at meso (organizational) or macro (societal) levels of ethical decision making. While perhaps less immediately obvious as an ethical dilemma to some individuals involved, these may constitute dilemmas that have even further reaching impacts for both individual professionals and impacted groups. These larger dilemmas may often seem beyond the scope of individual decision making, but indeed ultimately are primarily addressed through the contributed actions/decisions of individuals, typically as they interact in some group process. Of course, it should also be recognized that all ethical dilemmas, by definition, have some implications beyond the welfare of the most immediate individuals involved. The list of example dilemmas provided in Table 11–1 includes scenarios from each of these levels. These dilemmas might arise in a wide variety of settings and circumstances where health care is practiced or health care policy is set. Please identify the level of ethical decision making that each example seems to represent, and consider what ethical issues might exist for each scenario.

TABLE 11–1. EXAMPLE ETHICAL DILEMMAS

In the fifth edition of their foundational text Principles of Biomedical Ethics,17 Beauchamp and Childress address the following aspects of the moral life: principles and rules; rights, character and virtues; and moral emotions. The responsibilities (based on principles and rules) and rights of the health care provider and other involved parties will be addressed briefly in this chapter as considerations that must be dealt with in the course of responding to a specific dilemma. While acknowledging their importance, this chapter will not address the roles of character, moral virtue, or emotions in ethical decision making by health professionals. One might say that they constitute the provider’s inherent moral perspective that will direct and support his or her decision making. The interested reader is referred to the text referenced above for a fascinating discussion of these factors17; this discussion is continued in the 2008 edition of the same text for those wishing to review updated coverage of this material.18 The remainder of this chapter is intended to prepare and assist the pharmacist and other health professionals providing drug information to analyze and address dilemmas, such as those listed above. ![]() The primary focus will be on the health professional’s identification, interpretation, specification, and balancing of pertinent ethical rules and principles as he or she seeks to determine and justify what he or she considers the right decision or the best course of action.

The primary focus will be on the health professional’s identification, interpretation, specification, and balancing of pertinent ethical rules and principles as he or she seeks to determine and justify what he or she considers the right decision or the best course of action.

Basics of Ethics Analysis

This section briefly presents relevant terminology and definitions used in the field of ethics, as well as an overview of a specific process of analysis that may be used in assessing ethical dilemmas. In the section following this one, specific case scenario demonstrations of this process for analysis will be presented.

DEFINITIONS USED IN THE FIELD OF ETHICS

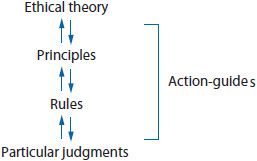

Beauchamp and Childress19 defined ethics as “a generic term for several ways of examining the moral life.” These authors described a process of deliberation and justification that is necessary when confronting a moral dilemma. They stated, “When we deliberate… we are considering which judgment is morally justified….” They indicated that, “Particular judgments are justified by moral rules, which in turn are justified by principles, which ultimately are defended by an ethical theory.” These authors presented a hierarchical diagram that depicts this approach to analysis (Figure 11–1). A later article by Beauchamp further addresses the need to consider these principles and rules within the specific context of the case at hand, in order to fully realize their action-guiding potential.20

Figure 11–1.

The authors referred to these hierarchical levels of analysis (particularly rules and principles) as action-guides, which are utilized to justify a particular judgment. They describe a rule of ethics as specific to context and relatively restricted in scope; for instance, the moral rule about confidentiality that specifically addresses a patient’s right to consent prior to release of privileged information.19 Principles are more broad and fundamental in scope; for example, the principle of respect for autonomy, which is the patient’s right to decide on personal issues. They describe ethical theories as “integrated bodies of principles and rules… that may include mediating rules that govern cases of conflicts.” The prominent rules and principles guiding ethical decision making by health care professionals can generally be placed within one of two broad ethical theories: consequentialist theory or deontological (derived from the Greek word deon, meaning duty) theory.19 Multiple versions exist of each of these broad categories. Consequentialist theories describe actions or decisions as morally right or wrong based on their consequences, rather than on any intrinsic features they may have. The two cardinal principles of consequentialist theory are beneficence (do that which promotes a good outcome) and nonmaleficence (do that which minimizes bad outcomes). Consequentialist theories focus on this one feature of an act, its consequences. For example, an informed consent ethical rule can be of value within consequentialist theory because consent generally results in improved compliance and outcome—good consequences. However, if informed consent was likely to result in a bad outcome, it would not be justifiable within consequentialist theory. A mediating rule utilized by many advocates of consequentialist theory is to hold nonmaleficence as more important, or more foundational, than beneficence.

Duty-driven (deontological) theories look more to intrinsic qualities of an act or decision to assert its moral rightness or wrongness. Deontological theory considers other inherent features of an act, besides consequences, as also relevant and often of greater importance. For example, in various forms of deontological theory, the act is considered inherently wrong if it is dishonest or breaks confidentiality, or if it does not respect individual autonomy. Conflicts between different rules are mediated by appealing to more foundational, underlying principles such as adherence to justice or to respect for persons.

Conscious recognition of the pertinent action-guides, and understanding mediating rules that operate within the health professional’s preferred ethical theory or theories, can help providers honestly and equitably analyze the ethical dilemma, and better comply with the imperative characteristics of ethical deliberation (see the beginning of this chapter).

OVERVIEW OF A SUGGESTED PROCESS OF ANALYSIS TO BE USED WHEN AN ETHICAL DILEMMA ARISES

In the article Hospital Pharmacy: What Is Ethical?, Veatch2 indicated that often people reach a particular ethical decision without a great deal of conscious deliberation, through moral intuition, and without subsequent challenge from any external party. However, on occasion, when pondering a certain ethical judgment, they are called on (internally or externally) to analyze and justify the basis for their conviction. He suggested that when this occurs, it is first important to understand the facts of the specific case. He then described progression through three additional process stages of reflection (on ethical rules, principles, and theories) by which we may identify, analyze, and present reasons for our judgment. In the same report, the author also emphasized the importance in one’s reflection of taking into account the points of view of all parties impacted. As stated earlier in this chapter, this is one of the key characteristics distinguishing an ethical deliberation. A survey of the text Cross-Cultural Perspectives in Medical Ethics, 2nd ed.21 demonstrates that there are many commonalities, but also important differences across the ethical perspectives of different cultures. These cultural perspectives must be considered if all parties’ points of view are to be taken into account.

In this section ![]() the application of a proposed process of ethical analysis is demonstrated for identifying, analyzing, and resolving ethical dilemmas that may arise during health professionals’ provision of drug information. These steps of analysis are derived from the writings of Veatch, Beauchamp, and Childress, as well as other authors.2,19,21–23 The process may be summarized as follows:

the application of a proposed process of ethical analysis is demonstrated for identifying, analyzing, and resolving ethical dilemmas that may arise during health professionals’ provision of drug information. These steps of analysis are derived from the writings of Veatch, Beauchamp, and Childress, as well as other authors.2,19,21–23 The process may be summarized as follows:

I. Identification of relevant background information

A. Factual details of the issue at hand

B. Consideration of who is affected by the ethical issue

C. Learn and respectfully address the cultural perspectives (including applicable legal requirements) for those affected by the dilemma

II. Identification and justification of the relevant moral rules and principles (action-guides) pertinent to the case

III. Deliberation, through the use of moral intuition and application of ethical theory, on how to rank/balance the rules and principles pertinent to the case in order to resolve the ethical dilemma

Step I. Identification of Relevant Background Information

![]() The first process step requires identification and evaluation of pertinent background information to ensure that the facts of the specific case are understood and to assess whether a true ethical dilemma exists. This first step deserves careful consideration and research. Once the facts of a case are known, the moral concerns may be resolved. This step has been divided into three parts: (a) data gathering, (b) consideration of the welfare of all affected parties, and (c) respect for the cultural perspectives of these parties.

The first process step requires identification and evaluation of pertinent background information to ensure that the facts of the specific case are understood and to assess whether a true ethical dilemma exists. This first step deserves careful consideration and research. Once the facts of a case are known, the moral concerns may be resolved. This step has been divided into three parts: (a) data gathering, (b) consideration of the welfare of all affected parties, and (c) respect for the cultural perspectives of these parties.

Health professionals already use data gathering when they apply a systematic approach to answering any drug information question (see Chapter 2). When addressing a potential ethical dilemma, the providers must learn about the factual details of the issue, who is directly involved, and whether there is conflict in factual understanding among the involved parties in the issue. For example, does the parent who calls to ask about the medication recently prescribed for her teenager already know that the teenager is taking a birth control pill prescribed by a gynecologist (rather than a dermatologist for acne) and simply wants to know the name of the product?

If the matter still seems to involve an ethical dimension once data gathering clarifies the facts, the next step is to consider the rights and responsibilities of all affected parties. As previously mentioned, this has been described as an essential component of any ethical deliberation.2 The health care provider, the direct client (patient or parent in the case just described), other indirect but individual clients (e.g., any existing or unborn children, parent paying for service provided to the child patient, or the patient’s spouse), other health professionals (e.g., the patient’s physician), other societal groups (e.g., other patients who might be harmed by an incompetent practitioner), and any higher power recognized by the health professional have rights and/or responsibilities that should be considered.

Finally, during first consideration of any potential ethical issue, the provider should take into account the cultures of the affected parties.22 In his reviews of the foundations of modern medical ethics theories, Veatch21,23 described how the unique perspectives of Western, Chinese, Hindu, Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, and other cultural groups have affected the formulation of their dominant medical ethics traditions. Other cultural classifications might include socioeconomic status, political affiliation, age category, and racial or ethnic group. A report by Najjar et al.24 demonstrates some important similarities (e.g., requests to assess physician recommendations) and differences (e.g., requests to serve as a primary health care provider) in the types of ethical dilemmas that are identified by drug information specialists functioning within the cultural environment of Saudi Arabia compared to those reported at the United States (U.S.) centers.

In a very interesting case study, Carrese et al.25 discussed the ethical obligations of medical professionals in caring for those of a different ethnic culture. In this case, a young Laotian mother had utilized a traditional Mien folk cure to treat her infant. The treatment involved placing several small burns on the child’s abdomen to treat gusia mun toe, an apparently transient, but very distressing, colic-like ailment. The cure resulted in several small scars, but no other obvious ill effects. The mother indicated that the cure worked. The physician recognized the value in supporting the positive impacts of the woman’s attachment to her cultural support group. However, the physician was confronted with the dilemma of how to respond to this mother’s revelation of a culturally promoted treatment measure that was not scientifically supported and could be dangerous. Sometimes, culturally based actions may conflict with the professional’s goal to avoid harm and promote benefit. However, failing to consider a cultural perspective may also have harmful effects. An extended discussion of how differing cultural perspectives affect ethical decision making is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, the health professional should strive to be aware of and respect the cultural perspectives of the affected parties when contemplating an ethical dilemma. The interested reader is encouraged to refer to the resources cited here and above for further discussion of cultural factors in ethical analysis.21,23

One final issue should be addressed relative to cultural considerations. The legal requirements of the society within which an ethical dilemma occurs are part of the culture and must be identified. A specific ethical decision will not always exactly conform to the existing legal requirements of society. The ultimate nature of ethical deliberations may result in decisions that are more demanding than the legal requirements and, unfortunately, may even occasionally involve perceived or true conflict with specific legal requirements. This may involve, for instance, a decision not to divulge confidential communications between a professional and client, which may or may not be acceptable within the law. In another case, the health professional may decide not to provide information related to abortion or capital punishment, even though these activities are acceptable within the law. Obviously, legal requirements cannot be ignored or dismissed lightly when making a specific ethical decision.

Step II: Use of Rules and Principles (Action-Guides) to Assist in Analysis of an Ethical Dilemma

If the dilemma persists, once the available background information has been identified and considered, the process of full ethical deliberation should proceed. Veatch2 suggests that the involved party/parties can proceed as far as necessary through successive stages of general moral reflection assessing at the level of moral rules and then at the level of ethical principles, within their accepted ethical theory. These might be described as the action-guides referred to by Beauchamp and Childress.19 This second process step of analysis will look at moral rules that may apply to the specific case and more general pertinent ethical principles. Definitions are provided at the end of this section for a number of ethical rules and principles that are considered particularly relevant to decision making by practitioners.

It should be noted that specific action-guides may be considered a rule within one ethical theory and a principle within another. For example, veracity (truth telling) as mentioned above, may be considered by some ethicists to be a specific moral rule and by others to be a general principle, depending on which ethical theory is followed. For the practitioner immediately involved in analyzing a specific ethical dilemma, defining the relevant action-guides as rules or principles is important only to the extent that this helps in assessing which are more fundamental to the issue at hand. Therefore, in this chapter, both rules and principles will be included within the same process step of ethical analysis.

Examples of moral rules within biomedical ethics include a confidentiality rule dictating that patient-entrusted information should not be disclosed or an informed consent rule that addresses the individual’s right to information before agreeing to a specific medical procedure. Unfortunately, there is no definitive list universally defining all moral rules and, sometimes, multiple pertinent rules can be in conflict. Furthermore, there are acceptable exceptions to most moral rules. For instance, disregarding the informed consent rule might be justifiable in an acute situation to protect the life of the client, suffering may be necessary in order to achieve cure of serious disease, and many consider killing justified under certain circumstances. Therefore, there may not be a specific rule that resolves a particular ethical dilemma.

When such a circumstance arises, the practitioner may begin a more general level of analysis by looking at the ethical principles that apply to the case. Sometimes, the involved parties can reach an acceptable resolution to an ethical dilemma once they recognize the more broad relevant ethical principles. In a given dilemma, the professional may decide that the primary principle is to respect the autonomy of the client and that requires providing complete information that enables the client to make an informed decision. In another dilemma, if do no harm is considered the most fundamental ethical principle, decisions or acts that deny this principle would be considered unethical. It becomes immediately obvious, however, that relevant ethical principles such as these may also come into conflict. This problem can be demonstrated by the following example: The professional may believe that full disclosure will result in nonadherence by the patient, with significant risk of resultant harm. The practitioner, therefore, confronts two conflicting principles: respecting client autonomy versus the duty to do no harm.

Step III: Ethical Theory as a Means to Clarify or Resolve Ethical Dilemmas

This third step of ethical analysis reveals how relevant moral rules and principles interact within the preferred ethical theory to address the given dilemma. When confronted with conflicting ethical rules or principles, the practitioner may simply resolve the dilemma through his or her moral intuition of the right thing to do; even if unconsciously, this reflects the individual’s at least temporary affiliation to some theory of what constitutes good versus bad or right versus wrong. ![]() Sometimes, the professional will find it necessary and valuable to more consciously deliberate on how various ethical theories suggest that the relevant rules and principles should be prioritized or balanced. According to Veatch,2 this process step can lead to more rational and honest decision making or action taking. He suggests that these ultimate deliberations at the level of ethical theory will be affected by our most basic religious and/or philosophical commitments. It is important that the practitioner recognizes and acknowledges the impact on decision making of his or her own personal ethical perspective. Those dilemmas that cannot be fully resolved can at least be viewed with greater clarity.

Sometimes, the professional will find it necessary and valuable to more consciously deliberate on how various ethical theories suggest that the relevant rules and principles should be prioritized or balanced. According to Veatch,2 this process step can lead to more rational and honest decision making or action taking. He suggests that these ultimate deliberations at the level of ethical theory will be affected by our most basic religious and/or philosophical commitments. It is important that the practitioner recognizes and acknowledges the impact on decision making of his or her own personal ethical perspective. Those dilemmas that cannot be fully resolved can at least be viewed with greater clarity.

Veatch23 states that, “The components of a complete theory will answer such questions as what rules apply to specific ethical cases, what ethical principles stand behind the rules, how seriously the rules should be taken, and what constitutes the fundamental meaning and justification of the ethical principles.” In this reference and another text, the author reviews the foundations of consequentialist, deontological, and other ethics theories particularly relevant to health professionals, including the Hippocratic tradition; Judeo-Christian and other religious-based traditions; the philosophies of the modern secular West; and medical ethics theories outside the Anglo-American West, including Socialist, Islamic, Hindu, African, Chinese, and Japanese traditions.21,23 Frequently, versions of the broad consequentialist and deontological theories are expressed in various ways across these traditions. Particular note should be given to the core of the various Hippocratic Oaths, since this has been the central ethical tradition of Western medicine: “Those who have stood in that (Hippocratic) tradition are committed to producing good for their patient and to protecting that patient from harm.”23 In Hippocratic tradition, there is also a special emphasis placed on the responsibility of the medical professional to the specific patient versus obligations to other less directly affected parties or to society in general. A contract theory of medical ethics has also been proposed, which describes an implicit (unwritten) contract between health professionals and patients.23 This modern theory is of special relevance to the pharmacist providing drug information as a service within an implicit pharmaceutical care contract.23,26 First of all, this theory represents a shift in thinking for those pharmacists who might have considered their primary obligation to be to the prescriber rather than to the patient. Furthermore, this contract between patients and professionals suggests an obligation for more substantive communication with patients and a higher level of caregiving than some pharmacists have previously felt obligated to offer. The reader is referred to foundational writings by Veatch, as well as those of Beauchamp and Childress, for a more in-depth discussion of various medical ethics theories.18,19,21,23

AN ANNOTATED LISTING OF RULES AND PRINCIPLES (ACTION-GUIDES) APPLIED IN MEDICAL ETHICS INQUIRY

The following rules and principles of ethical conduct will be described and subsequently used in the analysis of case scenarios provided in the next section. Their description will necessarily be brief. The reader is referred to other sources to read more about these rules and principles.19,23

1. Nonmaleficence—A basic principle of consequentialist theory; encompasses the duty to do no harm. This tenet has a long history as part of the Hippocratic tradition, where it has often been described in terms of the health care provider’s duty to the individual patient. The principle is also cited as justification for actions benefiting all. Sometimes, application of the principle requires addressing conflicts between the needs of one and all.18

2. Beneficence—Another basic principle of consequentialist theory that expresses the duty to promote good. Again, conflict can arise between what constitutes good for one individual versus the larger societal group. Good or bad consequences are also of importance within deontological theories, but are evaluated along with other principles that may be considered of equal or greater importance.18

3. Respecting the patient–professional relationship—A moral rule, often referring to respect for the physician–patient relationship, but also applicable to other professional–patient relationships. This rule has been mentioned in published reports of ethical dilemmas arising during the provision of drug information.24,27–29 As expressed in Hippocratic traditions, this rule indicates that the physician’s primary duty is to the patient and tends to give the physician, rather than the patient, control in the relationship, which may be judged paternalistic by some. This rule is particularly noted in duty-driven (deontological) ethical theories that consider the professional’s duty to the patient, but also supports consequentialist theory to the extent that good outcomes are enhanced.

4. Respect for autonomy—A principle described particularly within deontological theory. This principle is founded on a belief in the right of the individual to self-rule. It speaks to the individual’s right to decide on issues that primarily affect self.

5. Consent—A moral rule related to the principle of autonomy which states that the client has a right to be informed and to freely choose a course of action; for example, informed consent to receive a therapy or procedure.

6. Confidentiality

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree