Essential Hypertension

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Essential hypertension is one of the most common chronic diseases affecting adults. It can occur alone or in combination with comorbidities such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, congestive heart failure, and renal disease.

• ETIOLOGY

Hypertension is a state of persistently elevated blood pressure (BP) due to a wide variety of contributory factors. Excess sodium intake, sodium sensitivity, excessive neurohormonal production, or hypersensitivity (e.g., the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems) are well-identified contributory factors. Because of the complexity of the etiology, it is referred to as essential hypertension (EHT) to differentiate it from numerous much less common and in many cases curable, secondary causes such as pheochromocytoma, primary hyperaldosteronism, and coarctation of the aorta. There are also some medications (including OTC and herbal products) that may cause or aggravate BP elevations.

• DIAGNOSIS

It is important to understand the basics of blood pressure readings in order to effectively diagnose and assist patients in managing their hypertension. The top number of the reading refers to the systolic blood pressure and the bottom number refers to diastolic blood pressure. Systolic blood pressure is the amount of pressure exerted when the heart contracts. Diastolic blood pressure refers to the pressure in the arteries when the heart is at rest, passively filling. A diagnosis of hypertension is made in patients under 60 years of age with a blood pressure reading of greater than 140/90 on multiple occasions. New guidelines set greater than 150/90 as the diagnostic cutoff for patients 60 years of age and older. A single reading of a patient’s blood pressure above 140/90 and below 180/110 is not diagnostic as blood pressure can be raised during stress, infections, medication use, and exercise, or there are a myriad of errors in technique that can also provide falsely elevated blood pressure readings. However, a single blood pressure measurement >180/110 should be considered diagnostic of hypertension and a referral made so that therapeutic interventions can be initiated immediately.

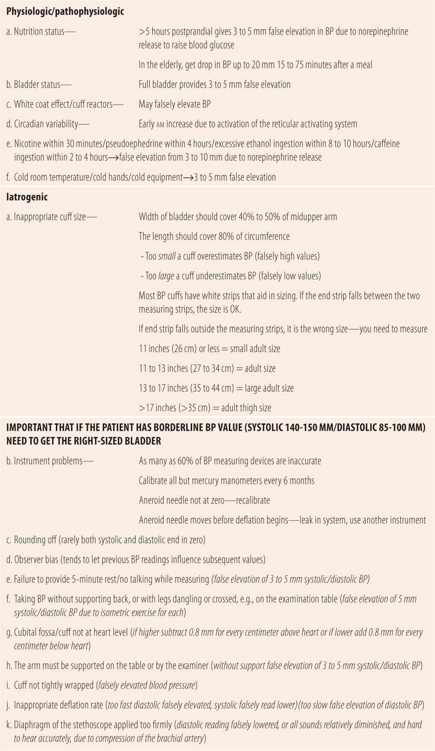

For most patients, the blood pressure goals are <140/90, even for patients with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. Accurate measurements of blood pressure are essential to the proper diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Blood pressure measurements elevated by 5 to 10 mm over the diagnostic criteria should be reassessed at different times of the day because many natural factors such as low blood glucose or a full bladder may cause blood pressure to vary throughout the day. In addition, many patients develop “white coat hypertension,” blood pressures elevations that only occur in the physician’s office and/or in association with a health care provider. To obtain more accurate and meaningful results, blood pressure readings at home should be measured if possible. If a total of at least three readings done at different times of the day and in different settings are all consistently above 140/90, then the diagnosis of hypertension can accurately be made and therapeutic interventions can be initiated. Marked differences in BP readings may be an indication for ambulatory BP monitoring to more accurately assess whether or not the patient has sustained blood pressure values in the hypertension range. An additional consideration in patients with borderline blood pressure levels is to make sure that the cuff size is accurate and that the cuff is centered over the cubital fossa.

• COMPLICATIONS

If not adequately controlled, hypertension can both directly and indirectly lead to complications and possibly death. Uncontrolled hypertension by itself is the leading cause of stroke and congestive heart failure. In addition, it accelerates the rate of atherosclerosis, leading to peripheral artery disease, angina, and myocardial infarction. Finally, by itself, but especially in combination with diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension can cause renal failure and blindness. It is well established that effective antihypertensive therapy (i.e., attainment of goal blood pressures) can drastically reduce the incidence of these complications. Therefore, the goal of antihypertensive therapy is to prevent these complications by lowering blood pressure to target values.

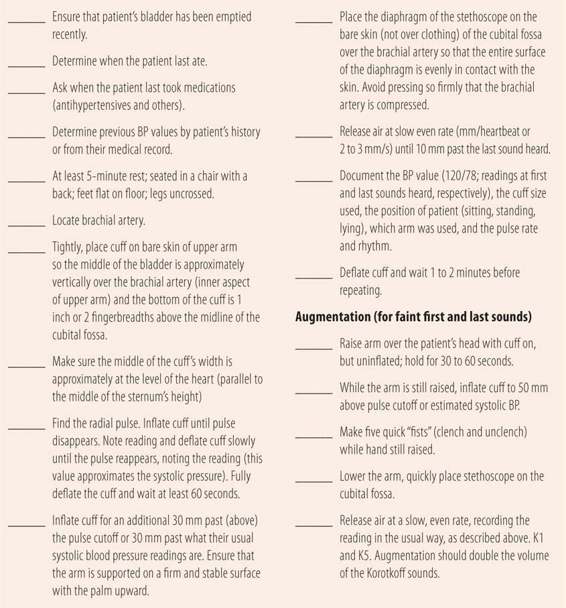

• BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

Unfortunately, due to a variety of factors, many blood pressure readings are inaccurate, causing inappropriate diagnosis and/or inappropriate changes in antihypertensive therapy. Even when taken by skilled medical personnel using proper techniques, blood pressure measurements with a sphygmomanometer on the upper arm with a stethoscope are at best within plus or minus 5 mm of the actual arterial pressure. Using inferior equipment (finger and wrist cuffs), inaccurately calibrated equipment, improper technique, and not addressing potential modifying factors (smoking, caffeine, etc.) can independently or in combination lead to errors of up to plus or minus 30 mm. Table 18.1 lists appropriate blood pressure measurement techniques. Table 18.2 lists common causes for error in measuring blood pressure, which need to be avoided or accounted for to optimize the accuracy of measurement. In addition to technique and other factors that influence blood pressure measuring accuracy, the setting in which the blood pressure is measured can have a significant impact. In patients with hypertension, the vast majority have white coat hypertension. That is, their blood pressure readings are significantly higher in the doctor’s office than they are at home or when done by a friend or family member. Therefore, exclusive reliance on office-based readings to guide antihypertensive drug therapy can lead to overmedication and unnecessary adverse effects such as orthostatic hypotension, which can lead to falls and injuries in the elderly. While home blood pressure readings may be preferred, not all home devices are equal in accuracy. There are international standards for validation of a device’s accuracy. However, not all brands meet those standards. There are two main sources of information regarding comparative accuracy. Every several years, Consumer Reports magazine compares the accuracy of various manufacturer’s devices. The report is available at the web site of the magazine, without a subscription. The other is the dabl Educational Trust web site (http://www.dableducational.com). Only those devices recommended by these two sources are of acceptable accuracy for home monitoring.

| TABLE 18.1 | Blood Pressure Technique |

| TABLE 18.2 | Common errors in Measurement of blood Pressure |

• INITIAL VISIT/WORKUP

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the initial visit and workup has four primary purposes: (1) assess target organ damage and comorbid diseases; (2) assess lifestyle for potential use of nonpharmacologic therapy; (3) collect baseline laboratory data to prospectively evaluate potential adverse drug reactions due to antihypertensive therapy; and (4) begin the education process for the patient and their social support system. Home blood pressure monitoring and educating patients on proper BP measurement techniques can begin at this time. A complete medical history and physical examination should be conducted, focusing on the presence or absence of angina, heart failure, stroke, and the metabolic syndrome. Lab tests that should be done include electrolytes, a glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) for diabetes, a complete fasting lipid panel for dyslipidemia, serum creatinine and urine microalbuminuria for renal damage, and liver function tests that can identify common comorbidities of hypertension and/or serve as baseline values for later evaluation of potential medication adverse effects. A careful history for salt, caffeine, and ethanol intake plus exercise patterns should be done. A smoking history should be obtained. Also, the patient’s willingness to undertake modifications to their lifestyle can be assessed. Appropriate weight loss, smoking cessation, an appropriate exercise program, and minimization of salt intake have all been shown to lower blood pressure and may be successfully used individually or in appropriate combinations in patients with blood pressures only slightly above diagnostic cutoffs. All these measures also augment antihypertensive drug therapy for BP control.

• FOLLOW-UP VISITS

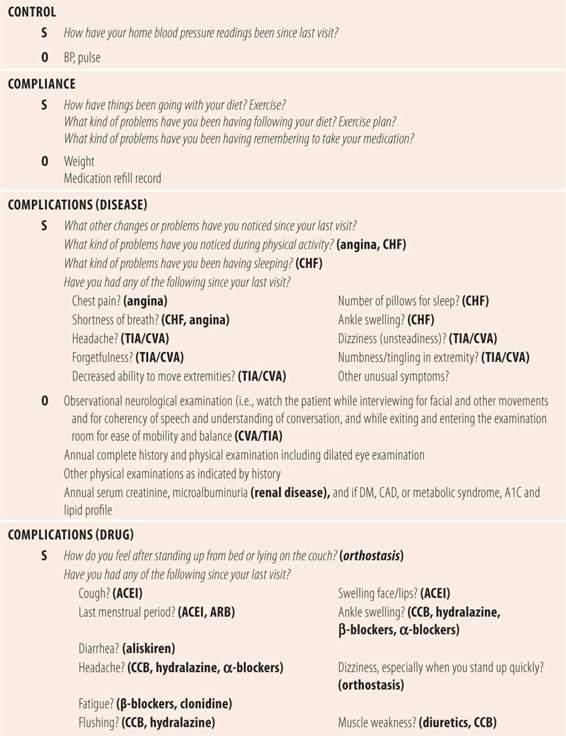

At each follow-up visit control of the disease, compliance with medication and lifestyle changes and any complications related to the drug or disease need to be assessed. Table 18.3 summarizes follow-up parameters and questions to be assessed at each visit.

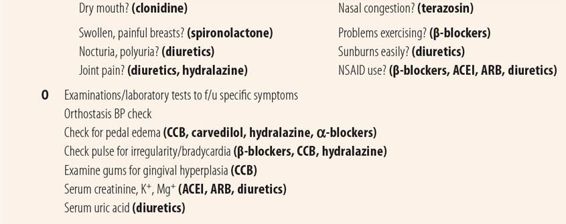

| TABLE 18.3 | Follow-Up Visit Hypertension |

Control

The target blood pressure for most patients with hypertension is <140/90 regardless of comorbid conditions such as diabetes and chronic renal disease. For patients 60 years of age or older, the new target goal is <150/90. Which blood pressures should be used to adjust the patient’s drug regimen? Currently, home blood pressures are preferred because of the high incidence of white coat hypertension among patients with hypertension. Using higher office-based blood pressures exclusively introduces the risk of inadvertently overmedicating the patient and inducing orthostatic hypotension.

Patients need to be educated on proper and accurate home blood pressure techniques. At each follow-up visit, remind the patient of the importance of being seated in a supporting chair with feet on the floor for several minutes, arm supported by table at heart level, the proper placement and position of the cuff in relationship to the brachial artery and the level of the heart, in addition to avoiding any modifying factors such as full bladder. Proper documentation of the readings is also important. Patients need to record the blood pressure with pulse rate along with the arm in which it was measured. Their position (sitting, standing, lying) and the time of the day should also be documented. To assess the relative accuracy of home versus office readings, the patient should periodically bring their electronic devices to the office to allow comparison of blood pressure readings with both the office and home devices. Bringing the home device to the office annually or when there seems to be a significant difference between home and office readings can also serve as the periodic review of patient’s home technique.

Initially, blood pressures should be taken several times a day. Ideally, this would include readings at home and at work. In elderly patients, at least one reading every day should be taken 30 to 60 minutes after a meal to assess postprandial drops in blood pressures. Most elderly patients with hypertension have a significant postprandial fall in blood pressure, which combined with the antihypertensive therapy may exceed 20 mm. Significant drops in blood pressure can be dangerous, leading to orthostasis or syncope, thus increasing the patient’s fall risk and/or precipitating symptoms of other comorbidities such as angina. While the exact cause of this effect is unclear at this time, its frequency and potential severity make it imperative that elderly patients take their blood pressure before eating and 30 to 60 minutes after beginning a meal to ascertain the level of this drop in blood pressure. With these multiple readings, the provider can more accurately adjust the timing and magnitude of any medication or dosage adjustments. It is important to recognize the variations in pharmacodynamic effects of various antihypertensive agents among individual patients. Multiple antihypertensive medications are listed as lasting 12 or 24 hours. However, in some patients the effect may only last 6 to 8 or 16 to 20 hours. This may lead to large gaps of time during which the blood pressure is well above target. In the case of a patient with well-controlled (or lower than desired) blood pressure in the afternoon or evening, but above target values in the morning, the single 24-hour dose can be split into two doses given 12 hours apart. Alternatively, the patient may be given one or more of their 24-hour duration antihypertensives in a single daily dose at bedtime rather than taking all medications in the morning.

One question that frequently arises relates to the safety of blood pressure values well below target values: can blood pressure be lowered too much? While most experts say attempting to achieve blood pressures near normal (120/80) is the ultimate target, others warn of decreased perfusion of vital organs and potential decreased survival. This so called J-curve is controversial. Common sense should direct adjustments in therapeutic regimens. The overall goal is to lower the blood pressure to below target values without adverse effects such as orthostatic hypotension or drug-specific adverse effects. Since elevated systolic pressure is probably more damaging, achieving blood pressure levels below the systolic target is probably most important. However, in some patients that may not be attainable without causing troubling side effects. In particular, in elderly patients, the arteries become less flexible (arteriosclerotic), causing the systolic pressure to be more elevated relative to the diastolic pressure. Sometimes this makes it difficult to attain target systolic pressure without lowering diastolic pressure too much. In that situation, have the patients return to measuring their blood pressure several times a day including after meals. Adjusting timing and dosage of existing medicines or changing medicines based on those pressures may enable adequate control. Recent studies in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes showed that lowering the target systolic pressure 20 mm (from 140 to 120) failed to further decrease overall cardiovascular mortality, which supports the adage: “Treat the patient, not the numbers!”

Another frequently asked question is, “How fast should the blood pressure be lowered?” Other than hypertensive emergencies (>200/120), the general rule is to decrease the blood pressure slowly. Lowering blood pressure too quickly, especially with parenteral agents, can precipitate manifestations of ischemia (in the brain, heart, or kidneys). Even adding oral medications too quickly can be counterproductive. First, a minimum amount of time is required for onset and especially maximal effect for each drug at each dosage. Additions made too soon could ultimately result in hypotension. Second, each new drug and dosage increment increases the chances of dose-related side effects. In addition, it takes time for patients to develop routines necessary for optimal adherence with the medication regimen and to learn to accurately measure home blood pressures. In patients with blood pressures >160/100, it is reasonable to initiate therapy with two medications. For patients with readings slightly above target values, a 6-month attempt at one or more lifestyle changes is warranted before initiating drug therapy. Once the blood pressure nears target levels, the emphasis should be on slowly lowering the blood pressure with small adjustments to the therapeutic regimen. Give each new change in therapy a month or more to take effect, since the full effect of many agents is not seen until 6 to 8 weeks after a dosage change or initiation of a new regimen. Once the home blood pressure readings are stabilized at desired levels over several consecutive office visits, all that remains is fine tuning the regimen to maintain its benefits. If pressures climb slightly, check for medication adherence issues or home device accuracy before considering alterations in the regimen. If pressures rise above target levels and all other explanations have been ruled out, have the patient increase the frequency of their testing and return in 30 to 60 days with their home device for an accuracy and technique check. If at that time the pressure remains elevated and no accuracy or technique issues are found, then small changes in the therapeutic regimen may be initiated. Similarly, if blood pressure readings continue to fall, check for orthostasis, recent weight loss, initiation or increase in intensity of exercise or diet programs, changes in levels of activity or stress, changes in hepatic or renal function, and overmedication.

Compliance

Medication refill records can be a source of objective information regarding medication adherence. Since a healthy diet, appropriate weight loss, and exercise all have a positive impact on lowering blood pressure, patients should be encouraged to lower salt intake, exercise regularly, and attain or maintain an ideal body weight in addition to any medication prescribed. At each visit, patients should also be asked about issues or problems with medication adherence and lifestyle changes, providing support, assistance, and positive reinforcement when appropriate.

Complications

At each visit, patients should be questioned regarding symptoms of congestive heart failure, stroke, angina, renal dysfunction, and visual problems. Start with one or more general open-ended questions. If answers are negative, follow up with “Have you had any of the following since your last visit…” listing each potential symptom of a complication in order. Yes answers need to be followed up using the chief complaint history technique. For the first few follow-up visits, make sure you explain the purpose of each of the questions, to educate the patient on things to look for, making sure that if they have any of those symptoms that may signal the onset of complications, they need to be seen immediately.

A complete history and a thorough physical examination are appropriate on an annual basis. The examination should include a dilated ophthalmoscopic examination. Additional annual evaluations include a serum creatinine and microalbuminuria determination to assess renal function, as well as an A1C and a fasting lipid profile in those patients with type 2 diabetes to detect common comorbid conditions. At each visit, an observational neurological examination can be done looking at cranial nerve function during the interview and evaluating motor function as they enter and exit the examination room. If questioning reveals headache or any other potential symptom of a stroke, a thorough neurological examination should be done.

Evaluating complications due to the medication is generally medication specific. Table 18.3 lists major problems with common antihypertensives. For example, for a patient on a thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic questioning about muscle weakness (not cramping) and observing patient’s ease getting up out of a chair help detect hypokalemia’s early impact on quadriceps muscle weakness. Checking for joint pain will evaluate patients for gout due to elevated uric acid levels depending on the drug therapy. Annual laboratory examinations for electrolytes, fasting glucose and lipids, and uric acid are also warranted. Similarly, with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) questions about cough and ununusual swelling of the face, mouth, or tongue are warranted. For all patients with blood pressure near or below target, the patient should be evaluated for orthostasis, probing for dizziness or light headedness at each visit and periodically measuring the level of orthostatic changes in blood pressure. This is done by first measuring the blood pressure in the normal manner with the patient seated. Then, while leaving the sphygmomanometer in place, have the patient stand. After properly positioning the cuff at heart level and supporting the patient’s arm, retake the blood pressure 30 to 60 seconds after standing. Deflate the cuff, and again repeat the measurement standing, about 1 minute later. A drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm or more or a drop in diastolic BP of 10 mm or more at either standing measurement is indicative of orthostasis and warrants adjusting drug therapy to prevent that drop. When checking for orthostasis in elderly patients, make sure to find out when they ate last.

• SUMMARY

The pharmacist, by training, is ideally suited to play a major role in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, including patient education and managing patient’s medication therapy through prescriptive authority. In addition to knowledge regarding diagnostic criteria and target blood pressure goals, the pharmacist needs to be the expert on the accurate measurement of blood pressure, avoiding the many environmental factors and the multiple potential errors in blood pressure measurement that can eventually lead to poor outcomes. Finally, the pharmacist must be able to fully assess the control of the patient’s blood pressure, assess and support adherence to pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment regimens, and assess the patient for the presence of complications from both the disease and the therapeutic regimen.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Frohlich ED, Grim C, Labarthe DR, et al. Recommendations for human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometers. Circulation. 1988;77:501A-514A.

2. Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometer Circulation. 1993;88:2460-2470.

3. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendation for blood pressure in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans. Circulation. 2005;111:697-716.

4. Ogedegbe G, Pickering T. Principles and techniques of blood pressure measurement. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:571-586.

5. Menash GA, Bakris G. Treatment and control of high blood pressure in adults. Cardiol Clin 2010;28 :609-622.

6. Acelajado MC, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, secondary hypertension and hypertensive crises: diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:639-654.

7. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. Evidenced-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (JNC-8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree