Enhancing Communication

Having served on various committees, I have drawn up a list of rules: Never arrive on time; this stamps you as a beginner. Don’t say anything until the meeting is half over; this stamps you as wise. Be as vague as possible; this avoids irritating the others. When in doubt, suggest a subcommittee be appointed. Be the first to move for adjournment; this will make you popular; it’s what everyone is waiting for.

–Harry Chapman

Many books describe the many theoretical and practical problems of communication and have proposed and discussed methods to overcome them. While most general issues relate to all organizations, some are particular to specific groups. This chapter focuses on viewing common communication issues and problems and, insofar as possible, as they apply within a pharmaceutical company.

Communication is an essential skill that is used during most of our waking hours and certainly during most of one’s time at work. The four parts of communication are (a) communicator, (b) message, (c) vehicle of communication, and (d) audience. The major tools used to communicate are listening, speaking, reading, writing, and body movement. In effective communication, the first four tools are used most often in descending order (i.e., we listen more than we speak, we speak more than we read, and we read more than we write). The great irony is that, in Western cultures, our formal education devoted to these four skills focuses on them in the opposite order (i.e., the most time is spent on developing writing skills and the least on developing listening skills).

One of the major means of enhancing communication is to teach people how to listen better and how to retain more of what they have heard. One process to do this is termed active listening (i.e., recapitulating what you have just heard in terms of the message delivered rather than the words spoken). It is a valuable tool that enhances communication by improving the likelihood that both speaker and listener have the same understanding of what has been said.

Barriers to effective communication and approaches that should improve the quality of communication are the first major issues discussed.

BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION

Barriers among Professionals in a Single Group

One of the most important barriers to effective communication involves a person’s hidden agenda. This term means that a person’s apparent goals are not their true ones. A person may purposely deceive or lie to another to hide the fact that he or she has a hidden agenda. Alternatively, the person may simply focus on selected aspects and not mention his or her true intentions. This problem can occur at all levels of a company and in any department. A simple example is an individual who pretends to have the company’s interest in mind but acts primarily on his or her own behalf. Although it is generally difficult to alter someone’s hidden agenda, understanding its existence may enable people to work together more effectively.

Another barrier to communication is poor listening skills. Few people are taught how to listen to others, and most people are so busy phrasing or constructing their response that they forget to listen or listen only partially to what is being said. A third barrier is individual accent; this becomes a barrier when people pay more attention to the way the other person speaks than they do to what the other person is saying. Nonetheless, it is difficult listening to a speech when it is difficult to understand what the person is saying because of their accent.

Barriers among Professionals in Two or More Separate Groups

In some pharmaceutical companies, it often seems that a marketing group prepares the specifications of what they want manufactured based on their beliefs of customer needs and wants and then throws the report over a wall to the production group. The production people look at the document and take the contents apart, reassemble it in their own terms, and then throw their response back over the wall to marketing. This process is usually repeated a number of times. Some marketing and medical groups also work in this out-of-date and grossly inefficient way. It is no surprise that significant delays, problems, and products that fail to meet customer needs generally result from this approach. Obviously, it would be preferable for both groups to sit down together and work jointly on first identifying customer needs and then solving or at least addressing the issues. Improved communication is not achieved, however, by merely having the relevant groups sit at the same table to work together. They must share a common outlook about their customer, the needs and wants of the customer, their company, and the style of drug development that is most appropriate. In addition, they must have a positive success-oriented vision of achieving goals in as rapid a time period as possible. Often, this does not happen because of the multiple barriers that exist between medical and marketing groups or between any two groups with different perspectives and goals.

Five categories of barriers are discussed in the following sections: cultural, functional, hierarchical, informational, and bureaucratic. While these barriers are described as existing between people in different groups (e.g., financial, medical, marketing, legal), they could generally be applied as well to professionals within a single group. There is no particular importance to the order in which these categories are discussed.

Barrier I: Cultural Separation of Professionals

In this chapter, culture is used to mean the way that professionals think based on their training, values, perspectives, and experiences. This type of barrier is more heterogeneous than the other four and is further broken down. The categories or factors that make up cultural separation include (a) type of professional training, (b) long-range versus short-range orientation, (c) primary focus on bottom line financial results or patient improvement, and (d) the different influences of financial rewards and professional recognition on personal motivation.

Professional Training of Scientists, Clinicians, and Marketers

Training and orientation of various professional groups create strong differences in outlook that may raise barriers to communication. For example, a scientist who wishes to withhold judgment until he or she has completed all necessary research will have difficulties communicating with a marketer who wants to see decisions made immediately to help a project move more rapidly toward clinical trials.

Some of the basis for the different approaches of scientists and physicians and the source of tensions between them becomes apparent when one looks at the respective training of each. A scientist’s training focuses on using a logical approach to either induce or deduce certain facts and conclusions. A scientist then challenges, modifies, and strengthens the truthfulness of those conclusions. They will withhold judgment and conclusions until all facts are obtained and considered. On the other hand, a physician’s training focuses on developing clinical judgment skills with the goal of becoming fast, accurate, and skillful at diagnosing and treating patients. A practicing physician often must reach a decision with data that are available, particularly in an emergency setting. It is often impossible for a physician to withhold judgment until a diagnosis is made (e.g., in an emergency situation), while it is usually possible for a scientist to wait until sufficient data are available from their experiments before reaching a decision. A marketing professional’s training focuses on achieving desired results (i.e., making a therapy available to a patient, or improving the bottom line) in the most rapid time and in the most efficient manner. This type of training focuses on the importance of expediency and of clearly differentiating between good or bad approaches to solving a problem or addressing a goal.

Long-range versus Short-range Orientation of Scientists and Marketers

Pharmaceutical company scientists working on long-range projects (often referred to as basic research) may not expect a potential drug to evolve from their work for up to ten to 20 years. The work of other scientists in the same company is much closer in time to when they expect to make a discovery. Their hope is usually to identify a specific compound for development within a one-to three-year period. Even at that stage, another five to ten or more years is often required to bring their discovery to the market.

In most other industries, marketers plan in terms of months for the development of new products. Their training promotes this short-term horizon as a reasonable period to see results of changes they institute in a product or its promotion either in terms of sales or access by a group who has stated a need for such a product. In the pharmaceutical industry, developing and marketing over-the-counter drugs and many line extensions of marketed products have a much shorter time horizon than that of new prescription drugs. Nonetheless, there is often a tension between marketing and medical personnel created by the impatience of many marketers with what they perceive as a slow development pace within research and development (R and D) groups, which often is coupled with what they perceive as a failure of some R and D staff to possess a “sense of urgency” in expediting the development process. (The other thing that contributes to this is proximity to the customer; let’s use a rare disease example. Many scientists have never seen a patient with Pompe disease. As part of their job, marketers are involved in identifying customer needs. Thus, they interview physicians who interview Pompe patients, the heads of patient support organizations, parents, and, in some cases, children with the disease. The firsthand knowledge of the issues faced by these patients leads to a sense of urgency that may not be felt by others on the team who are more removed from the personal circumstances faced by the individual patient.)

Focus on Financial versus Clinical Results

It used to be stated that marketers tend to be oriented, more than medical staff, toward financial outcomes of a new drug, and medical personnel tend to be more oriented toward clinical outcomes. However, this has generally become a myth if it ever was correct. The company must assess whether these orientations create barriers to effective communication between the two groups. The personalities of the specific people involved will determine the strength of these barriers, as will the steps the company has taken to minimize or eliminate them. Any company that identifies such problems should address them by uniting the groups with common company-oriented goals and gaining a better understanding of the orientation and thinking of other groups within the organization.

Motivating Factors

To understand another professional, it is usually vital to perceive the major factor(s) that motivates that individual. This is particularly true if one wishes to improve or alter that person’s performance. The motivating factors that influence medical and marketing staff sometimes differ. Knowing whether a hidden agenda exists is often difficult, and learning what it is (if present) can be impossible, but one should try to understand the true motivations of a person one is negotiating or interacting with. On the other hand, such distinctions as “scientist” versus “marketer” are very arbitrary. In this era, many marketers were originally trained as nurses, physicians, PhDs, pharmacists, genetic counselors, and other healthcare professionals.

Medical personnel derive enormous satisfaction from being part of or leading a team that is developing an important new drug that will help many patients. The more important the drug is in terms of its breakthrough qualities and medical benefits, the greater is this positive feeling. In addition, many medical personnel have various opportunities to achieve professional recognition, not only within their company, but also at outside professional meetings where they are asked to present papers, chair sessions, sit on panels, serve as officers of societies, receive prizes, and so forth. Writing articles, editorials, and chapters in books and reviewing manuscripts are common publication activities of many scientists and clinicians as well as for many professionals on the commercial side of the business.

Barrier II: Inappropriate Separation of Professionals into Departments or Divisions

Each discipline conducts its own functional activities at multiple hierarchical levels (e.g., divisions, departments, sections). The separation of some (or many) activities between marketing and medical (or other disciplines) is necessary and important. However, an additional inappropriate type of separation may occur because the company has not placed both medical and marketing representatives on the same project teams, committees, task forces, and other groups. This makes communication among professionals more difficult in important arenas where (a) decisions are made, (b) teamwork is fostered, and (c) understanding develops. This is a relatively easy problem to remedy or improve, as long as the senior managers understand the importance of lowering barriers and encouraging interactions between groups representing different disciplines.

Barrier III: Hierarchical Separation of Professionals

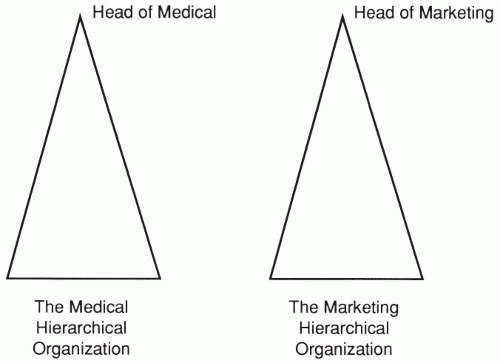

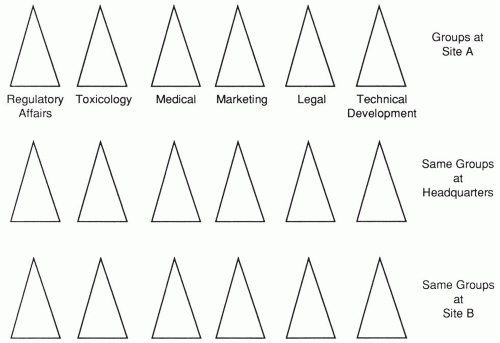

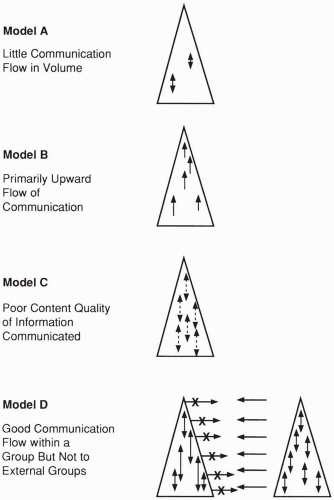

The medical and marketing functions may be conceptualized as pyramids (Fig. 22.1). Communication within and also between the pyramids must be organized to some degree, or it would be random, and gross inefficiency would generally result. If one listened with a stethoscope to the medical (or marketing) pulse within the pyramid in many companies, great differences would be apparent. In some companies, very little communication would be occurring because managers were holding onto information and not discussing it with relevant staff either above or below them within the pyramid or with others who are at the same level also within their pyramid. In other companies, there would be a large amount of important communication and dialogue, but on closer listening, it would be noted that it was all flowing in one direction, generally toward the top of the organization. In yet other companies, effective communication would be flowing both upward and downward within each pyramid, but little or none would be flowing between the pyramids. In other companies, there would be a large volume of communication, but the quality of information conveyed would be inadequate. Other patterns could be described that indicate specific types of problems (Fig. 22.2), particularly when multiple groups and multiple sites are considered.

Figure 22.2 Four models illustrating basic communications problems. Models A to C are problems within a group, and Model D is a problem between groups. |

A pharmaceutical company must ensure that adequate communication flows both within each pyramid (upwards and downwards) and between all relevant pyramids. It is obviously inadequate if the heads of medical and marketing communicate adequately but their subordinates do not (or vice versa). Each level within the company’s hierarchy must communicate effectively for the entire process to operate efficiently.

The actual situation is far more complex in pharmaceutical companies that have more than the typical two large pyramids and several smaller ones (e.g., finance, production, legal, personnel) and is further complicated in companies in which partnership, co-development, or co-marketing arrangements exist; these international companies can have several large pyramids in different countries (Fig. 22.3) or within different companies. Many of these pyramids speak different languages, have different cultures, and appear to think and behave differently. Some of these pyramids create communication problems for the other major pyramids. The principles for ensuring effective communication with foreign pyramids are no different than those for communicating with any other single group or groups. The first step is a desire by both parties to improve and maintain appropriate communications. This obvious and apparently straightforward goal sometimes takes many years and major efforts to achieve in many pharmaceutical companies, particularly in certain countries or cultures or with certain managerial styles (e.g., dictatorial).

Barrier IV: Information Separation of Professionals in Different Areas: Sharing Information

Unless professionals are interested in sharing information, effective communication cannot occur. Relying solely on the interest or desire of most professionals to communicate effectively is insufficient for a pharmaceutical company. There will always be some people in a company who can unilaterally disrupt the flow of information and effectively short circuit important activities. Unfortunately, many of these people apparently enjoy this role.

Both a clearly stated policy and a culture of following open and full communications are needed within each organization. Enforcement of that policy is needed when it is not adhered to. First, the policy should be established that all relevant information is always shared among those who “need to know.” Beyond the setting of policy is the setting of example. Management should be very cognizant of communicating in a way that is consistent with the organizational policies because the culture will be set based on the written policies and unwritten behaviors of those in leadership positions. Second, people in other groups (medical to marketing or vice versa) who would benefit from the information, even though it is only “nice to know,” should also receive it. Third, people within one’s own group who would benefit from the information generally should receive it.

This policy or any policy on communication (i.e., dissemination) of information is difficult to implement fairly and consistently. It depends on many interpretations that are made daily. Some people believe the policy described is incorrect because it results in too wide a dissemination of information within the company. Because having and holding onto information is a type of power, many people believe that telling others about various findings is inappropriate. Clearly, there is a balance, but overly restricting information can lead to decreased motivation, efficiency, creativity, and productivity and will lead to poor decisions by managers who do not have sufficient information. In addition to these motivations for not distributing information, there are some people who hold onto information because of fear—usually fear of being replaced. Good companies work on making a career path obvious, and good people are coached that in order to be “promotable,” you must be replaceable.

Barrier V: Bureaucratic Separation

Another aspect of this barrier is the many bureaucratic systems that may be enacted within and between groups. Standard operating procedures may seem to create problems for accomplishing one’s objectives rather than helping to facilitate one’s work.

How to Assess Communication Barriers

When people do not desire to communicate with other groups, many reasons can be found to justify their behavior, and many barriers can be created by these individuals. This problem may occur even if an individual is communicating to a higher organizational level. It is the responsibility of the company to ensure that this problem is either nonexistent or minimal. For example, individuals who continually refuse or simply do not follow the organization’s policy on communicating information must be instructed about acceptable standards and behavior. The author knows some perennial offenders of this principle who act like small children in the apparent belief that receiving negative attention is better than receiving none.

While a series of interviews or a thorough review could be conducted by external consultants to assess communication barriers within a company, a well-designed and critiqued questionnaire could be constructed (and used) by the company. It could be given to most employees in the relevant group(s) every two or three years to observe trends in communication styles and effectiveness. This process could also evaluate the impact of specific efforts implemented to remedy problems identified in previous questionnaires. Statisticians and other professionals should be involved in (a) designing the questionnaire, (b) assessing its validity, (c) determining its timing, (d) determining the size of the group to receive it, (e) assessing the issue of anonymity of responders, (f) deciding who will conduct the analysis, and (g) deciding who has access to the data generated by the questionnaire. Many believe that a survey, no matter how well constructed, will not yield valid results if conducted by the company. Often, if there are communication barriers, there is also mistrust. When there is mistrust, there is not usually a willingness to answer honestly (i.e., poor communication continues to the level of such survey tools). An outside group usually needs to be hired by a company and then to build trust with those to be surveyed, conduct the survey, and report the results in a way that vendor staff are sufficiently blinded and that results will be addressed without ramifications for individuals involved.

One or more of the steps could be conducted by outside contractors hired by the company. The emphasis must be on developing as high a quality instrument as possible to benefit both the company and its employees. Any approach to this project that does not adhere to the highest scientific and ethical standards will make the project one of ridicule by the employees and will not obtain valid data on which to base decisions.

TEARING DOWN SILOS AND WALLS

Silos

Every company has silos to one degree or another. They are a manifestation of any organization, no matter how flat. The more hierarchical the organization, the more likely it is to have a stronger group of silos. The term silo refers to a group that is created to function as one unit and tends to primarily interact and communicate within the group but not communicate and work with others who inhabit other silos. A large silo is likely to have a series of progressively smaller and smaller silos within it. For example, the R and D function could be considered as a single large silo in most companies. Corporate administration, finance, marketing, and production could be considered as others. Within each of these are various departments, and within departments are sections and possibly smaller groups that could be considered smaller silos.

The problem with silos is that people within them often find it difficult to work with outsiders as effectively as they do with those within their own group. An equally important aspect is the lack of effective communication between silos.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree