Endoscopic Therapy in the Management of Esophageal Varices: Injection Sclerotherapy and Variceal Ligation

Jake E.J. Krige

Stephen J. Beningfield

Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension is a clinical syndrome defined by a portal venous pressure gradient exceeding 5 mm Hg. A portal venous pressure gradient above the critical threshold value of 12 mm Hg causes clinically significant manifestations of portal hypertension in the form of compensatory portosystemic venous collateral formation, increased splanchnic blood flow, and disturbed intrahepatic and pulmonary circulation. These also give rise to the important complications of chronic liver disease, which include variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, hepatorenal syndrome, recurrent infection, and coagulopathy. Esophagogastric varices are part of the collateral venous system that diverts high-pressure portal blood via the coronary, short gastric, and esophageal perforator veins en route to the azygous system. These varices are the major source of hemorrhage and mortality, although bleeding from congestive gastropathy and anorectal varices and other sites may also occur. Epigastric and abdominal wall collateral vessels may enlarge with recanalization of the umbilical vein, and multiple retroperitoneal collaterals may form, which complicate surgical intervention. Splenomegaly and hypersplenism develop with impeded splenic vein outflow.

Cause

Two mechanisms lead to portal hypertension: (a) increased portal resistance and (b) increased portal flow. Increased resistance to flow is classified as presinusoidal, sinusoidal, and postsinusoidal (Table 1). Increased flow is uncommon and is caused by either arteriovenous fistulae or increased splenic arterial flow. Portal hypertension has a wide variety of causes and geographic prevalences; while cirrhosis is the most common cause in the Western world, schistosomiasis is the leading cause in many other countries.

Natural History

Variceal bleeding is the final step in a sequence of events initiated by an increase in portal pressure, and followed by the development of varices with a progressive increase in size. A key factor in variceal bleeding is an increase in the hydrostatic pressure inside the varix, with a resultant increase in variceal size and a decrease in wall thickness. Variceal rupture and bleeding occur when transmural variceal pressure and the increased tension in the thin wall exceed a critical value determined by the elastic limit of the vessel wall.

Variceal bleeding is the most serious complication of portal hypertension and

substantially alters the natural history of patients with compensated cirrhosis. One-third of deaths from cirrhosis are related to portal hypertension, and are due mainly to esophageal variceal bleeding. Up to 20% of initial variceal bleeding episodes are fatal, and as many as 70% of survivors, if inadequately treated, have recurrent variceal bleeding.

substantially alters the natural history of patients with compensated cirrhosis. One-third of deaths from cirrhosis are related to portal hypertension, and are due mainly to esophageal variceal bleeding. Up to 20% of initial variceal bleeding episodes are fatal, and as many as 70% of survivors, if inadequately treated, have recurrent variceal bleeding.

Table 1 Causes of Portal Hypertension | |

|---|---|

|

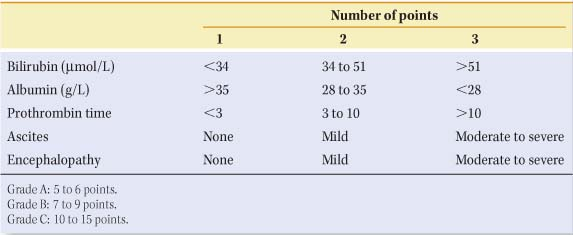

Table 2 The Child–Pugh Classification of Functional Liver Status | |

|---|---|

|

The ideal treatment of portal hypertension and bleeding varices should be universally effective, safe, easy to administer, and inexpensive. Currently no such treatment exists and the surgeon is obliged to select the most appropriate intervention from a menu of available therapeutic options, none of which is ideal or applicable to all patients. The rational treatment of esophageal varices depends on a clear understanding of the risks of rebleeding and the response to each specific intervention. The optimal management of bleeding esophageal varices requires a full appreciation of portal, gastric, and esophageal venous collateral anatomy, the pathogenesis and hemodynamic consequences of variceal bleeding, and the utility of each available therapy at specific stages in the natural history of portal hypertension.

The treatment of variceal hemorrhage has evolved markedly in the past decade. Although these advances in treatment have reduced overall mortality, uncontrolled or recurrent bleeding from varices and the consequences of progressive liver failure remain the commonest causes of early death in alcoholic cirrhotic patients. The spectrum of interventions required to control variceal bleeding and achieve efficient and successful treatment of the severe and potentially life-threatening complications of portal hypertension are invasive and complex and may necessitate advanced skills. No single modality is applicable to all patients, and knowledge of the alternatives allows the well-informed surgeon to choose the appropriate therapy for each clinical situation. A coordinated multidisciplinary team approach is essential as various therapies may be required at different stages in different patients.

Endoscopic treatment has become the principal first-line intervention in patients with bleeding esophageal varices, both during the acute event and for long-term therapy to prevent recurrent bleeding. After control of the index bleed, there is a 70% chance of rebleeding, with a similar mortality. The risk of rebleeding is greatest during the first few days after initial variceal hemorrhage. Survival after variceal bleeding depends largely on the rapidity and efficacy of initial primary hemostasis and the presence and severity of underlying liver disease and hepatic functional reserve. Early rebleeding has been shown to be a strong predictor of overall mortality and recurrent variceal bleeding substantially increases the risk of complications, which further contribute to mortality, emphasizing the need for rapid and sustained control of variceal bleeding as the principal imperative of endoscopic intervention.

Careful assessment of hepatic functional reserve is necessary before selecting the appropriate treatment. Although dynamic tests of hepatocellular function such as aminopyrine breath test, galactose elimination capacity, and hepatic amino acid clearance have been used in the past, the Child–Pugh and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores are currently the most useful and practical predictors of survival in cirrhotic patients (Table 2). For example, the operative mortality for Child–Pugh grade A patients is less than 5%, while for Child–Pugh grade C it exceeds 25%.

In Western countries, variceal bleeding accounts for approximately 7% of all upper gastrointestinal bleeding, although this varies geographically (11% in the United States, 5% in the United Kingdom) depending on the regional prevalences of alcoholic liver disease and viral hepatitis.

Management of Acute Variceal Bleeding

Choice of Therapy

The possibility of variceal bleeding should be considered in all patients who present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and have known risk factors for chronic liver disease or clinical evidence of portal hypertension. The modern management of acute variceal bleeding requires a variety of therapeutic options to be available for use either sequentially or in combination in individual patients (Table 3). Several important clinical considerations influence the choice of therapy, as well as the prognosis in individual patients. These include the natural history of the disease causing the portal hypertension, the location of the bleeding varices, residual hepatic function, the presence of associated systemic disease, continuing drug or alcohol abuse, the patency of major splanchnic veins, and the response to each specific treatment.

General Strategy

Variceal bleeding is a medical emergency and all patients with suspected acute variceal bleeding therefore require urgent hospitalization and standard resuscitation as for any major hemorrhage to be initiated. The immediate aims of emergency treatment are hemodynamic stabilization, blood-volume

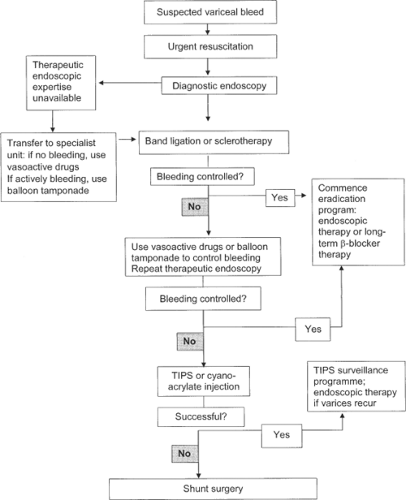

replacement, control of bleeding, support of vital organ function, and prevention of complications due to hypovolemic shock and impending liver failure. Patients should be managed in an intensive or high-care unit with a full staff complement including intensive care specialists, endoscopists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, intensive care nurses, and surgeons. Although variceal bleeding may stop spontaneously in up to 60% of patients, it is not possible to predict which patients will continue to bleed and require further specific emergency therapy. If an experienced medical team is not available at a peripheral hospital, patients should be transferred to a center with appropriate facilities, resources, and expertise as soon as they have been adequately resuscitated and are stable as subsequent management may be complex should bleeding continue or recur and may later require advanced multidisciplinary investigations and therapy. A suggested management algorithm is given in Figure 1.

replacement, control of bleeding, support of vital organ function, and prevention of complications due to hypovolemic shock and impending liver failure. Patients should be managed in an intensive or high-care unit with a full staff complement including intensive care specialists, endoscopists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, intensive care nurses, and surgeons. Although variceal bleeding may stop spontaneously in up to 60% of patients, it is not possible to predict which patients will continue to bleed and require further specific emergency therapy. If an experienced medical team is not available at a peripheral hospital, patients should be transferred to a center with appropriate facilities, resources, and expertise as soon as they have been adequately resuscitated and are stable as subsequent management may be complex should bleeding continue or recur and may later require advanced multidisciplinary investigations and therapy. A suggested management algorithm is given in Figure 1.

Table 3 Management of Acute Variceal Bleeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Initial Measures

Many patients with acute variceal hemorrhage also have liver decompensation with encephalopathy, ascites, coagulopathy, bacteremia, or malnutrition. The extent and urgency of initial therapy depends primarily on the severity of bleeding. Stable patients with intermittent bleeding are candidates for endoscopic therapy, while the infrequent patient with exsanguinating bleeding may require balloon tamponade to control bleeding before endoscopy is performed.

Maintenance of a secure airway and prompt resuscitation with restoration of circulating blood volume are vital and precede any diagnostic studies. Intravenous access is obtained via a central venous cannula. While blood is being cross-matched, crystalloid solution is rapidly infused until the blood pressure is restored and the urine output (as measured with a Foley catheter), is adequate. Infusions of normal saline may aggravate ascites and must be avoided. Overzealous expansion of circulating blood volume should be avoided as this may cause an increase in portal pressure and precipitate further variceal bleeding. The goal is to maintain the hematocrit between 25% and 30% and the central venous pressure should be no greater than 2 to 5 cm H2O, measured from the sternal angle. Patients who are hemodynamically unstable or the elderly or those who have cardiac or pulmonary disease should be monitored using a pulmonary artery catheter because injudicious administration of crystalloids, combined with vasoactive drugs, may lead to rapid onset of edema, ascites, and hyponatremia. Clotting factors are often deficient and fresh blood, fresh frozen plasma, and Vitamin K1 are frequently required. Platelet transfusions may be necessary. Sedatives should be avoided if possible.

Pharmacological Therapy

The role of vasoactive drugs is to reduce variceal pressure by decreasing variceal blood flow. The selection of a specific drug depends on local resources. The most widely used drugs are terlipressin, somatostatin, and octreotide. In the past, continuous intravenous infusions of vasopressin at 0.4 units per

minute combined with glyceryl trinitrate (given as a sublingual tablet or applied as a skin patch) were used. Vasopressin is seldom used today because the newer drugs have fewer side effects and are more effective. Terlipressin (Glypressin), the synthetic analogue of vasopressin, has the advantage of being effective in 2 mg intravenous bolus doses administered 4 to 6 hourly and is simpler to administer. Early administration of Glypressin in a French study showed improved survival.

minute combined with glyceryl trinitrate (given as a sublingual tablet or applied as a skin patch) were used. Vasopressin is seldom used today because the newer drugs have fewer side effects and are more effective. Terlipressin (Glypressin), the synthetic analogue of vasopressin, has the advantage of being effective in 2 mg intravenous bolus doses administered 4 to 6 hourly and is simpler to administer. Early administration of Glypressin in a French study showed improved survival.

Somatostatin does not cause systemic vasoconstriction unlike vasopressin, but reduces splanchnic and hepatic blood flow. Somatostatin is administered empirically as an initial bolus dose of 250 μg, followed by a continuous intravenous infusion of 250 μg/h. This is maintained until the patient is free from bleeding for 24 hours. Therapy may be maintained for up to 5 days to prevent early rebleeding. Major side effects with somatostatin are uncommon, although minor side effects such as nausea and hyperglycemia occur in one-third of patients. Octreotide is a somatostatin analogue with a longer half-life. This is given as an initial bolus of 50 μg followed by an infusion of 50 μg/h that can also be maintained for up to 5 days. The safety profile of octreotide is similar to somatostatin.

Most endoscopy units recommend that pharmacological therapy be commenced when a diagnosis of variceal bleeding is suspected and before emergency endoscopy is performed. This policy has the theoretical advantage of controlling bleeding before the initial endoscopy, which should make both diagnosis and immediate endoscopic therapy easier.

Emergency Endoscopy and Immediate Endoscopic Therapy

Emergency diagnostic endoscopy is mandatory to confirm that a patient is bleeding from esophageal varices. Patients with varices can usually be separated into three groups: those with active variceal bleeding, those with variceal bleeding that has stopped, and those who have varices but are bleeding from another site such as a peptic ulcer, hemorrhagic gastritis, or portal hypertensive gastropathy. These other lesions are treated appropriately.

Emergency endoscopy should be performed in an endoscopy unit with all the necessary equipment available. Many units have a fully equipped mobile emergency endoscopy trolley that can be wheeled into the operating room or the intensive care unit as necessary. It is imperative that full resuscitation facilities are available, together with skilled staff experienced in dealing with emergencies. Two endoscopy assistants should be present throughout the procedure. Adequate monitoring and effective suction are also essential during endoscopy. Emergency endoscopy should not commence until satisfactory venous access and central venous pressure measurement are established and volume replacement and resuscitation procedures including blood transfusions have been initiated to correct hypovolemia. If bleeding is profuse or if the patient is stuporous, endotracheal intubation is essential before starting endoscopy to protect the airway and avoid aspiration of blood or gastric contents.

Patients with endoscopically proven active variceal bleeding or those in whom variceal bleeding has stopped should have immediate endoscopic intervention using variceal band ligation or sclerotherapy (Fig. 1). If variceal ligation or sclerotherapy is deferred until the next elective endoscopy list in patients who have stopped bleeding, there is a distinct danger of further major acute variceal bleeding during the interval period, with substantial morbidity and mortality. If acute or recurrent major variceal bleeding continues despite endoscopic and pharmacological therapy, mechanical control by balloon tamponade is required.

Failed Emergency Endoscopic Therapy

Endoscopic therapy is successful in controlling acute variceal bleeding in over 90% of patients after one or two treatment sessions. Current evidence suggests that variceal ligation is as effective as sclerotherapy during acute variceal bleeding episodes. Any patient who rebleeds after two successive emergency endoscopy treatments during a single hospital admission has a prohibitively high mortality if further endoscopic therapy is pursued. Such patients should have a balloon tube inserted, be resuscitated, and then be treated by an alternative technique. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure may be recommended for patients who continue to bleed despite two endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy sessions. In patients being considered for liver transplantation, a TIPS procedure is now the preferred treatment to provide a bridge to transplantation.

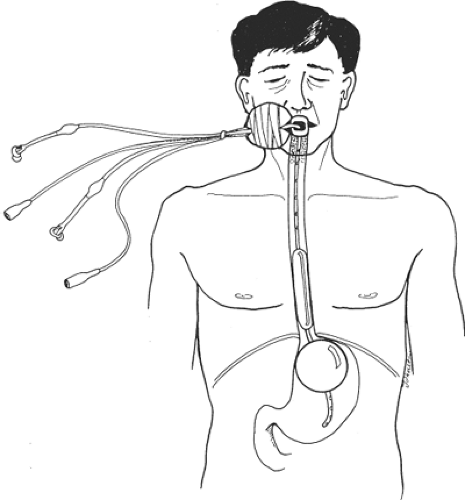

Balloon Tube Tamponade

Acute variceal bleeding can be temporarily controlled by a correctly placed balloon tube (Fig. 2). If the patient continues to

bleed after a balloon tube has been inserted and the balloon is confirmed to be correctly positioned, a further emergency endoscopy is required. Repeat endoscopy usually reveals another bleeding lesion that was overlooked or obscured by blood during the first diagnostic endoscopy.

bleed after a balloon tube has been inserted and the balloon is confirmed to be correctly positioned, a further emergency endoscopy is required. Repeat endoscopy usually reveals another bleeding lesion that was overlooked or obscured by blood during the first diagnostic endoscopy.

The balloon tube should always be inserted by an expert. The technical details are presented later. The tube should be left in situ for as short a time as possible (<24 hr) while the patient is being resuscitated and preparations are being made for endoscopic treatment. A balloon tube is also used when emergency endoscopic therapy cannot be successfully performed because visibility is obscured by major variceal bleeding, or when patients have continued active variceal bleeding despite attempted endoscopic therapy.

Alternative Emergency Management Options

The main secondary alternatives to primary pharmacological and endoscopic therapy for acute variceal bleeding are TIPS stenting, portosystemic shunts, esophageal transection operations, and liver transplantation. In patients with recurrent bleeding, it is crucial to identify the cause and site of bleeding, because the management of recurrent variceal bleeding, gastric varices, injection-induced esophageal ulceration and portal hypertensive gastropathy differs.

A TIPS shunt is the emergency procedure of choice in patients in whom endoscopic therapy has failed to control bleeding. Recent data confirm the utility and efficacy of TIPS stent as a salvage procedure for refractory variceal bleeding unresponsive to endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment. Immediate control of variceal bleeding is achieved in over 90% of patients who have undergone a TIPS stent. However, TIPS in patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding still has a high mortality. Prognosis is also poor if patients have developed sepsis, require inotropic support and ventilation, or have deteriorating liver and renal function. Established renal failure in a decompensated cirrhotic patient with uncontrolled bleeding is a contraindication to TIPS placement in most units.

The need for emergency surgical shunts to control acute variceal bleeding has diminished dramatically in the past decade due to the improved efficacy of pharmacological, endoscopic, and radiological treatment. While a successful surgical shunt effectively stops acute variceal bleeding and prevents recurrent bleeds, the role of emergency shunting procedures is currently restricted to patients who have failed endoscopic therapy and cannot be salvaged by a TIPS stent for technical reasons. This is because emergency shunt surgery has an operative mortality of up to 25%, which is largely determined by the degree of liver decompensation.

A variety of devascularization and transection operations that disconnect the high-pressure portal system from the esophageal varices have been devised. As a basic principle, the most simple procedure should be used. Simple esophageal transection using a staple gun is the preferred procedure for patients in whom endoscopic therapy has failed and TIPS or an operative shunt is not feasible. Previous sclerotherapy may increase the difficulty and risk of performing the operation due to sclerosant-induced ulceration and periesophageal fibrosis. Esophageal transection combined with extensive esophageal and gastric devascularization is not justified in the emergency setting. However, four trials that have compared sclerotherapy with esophageal transection and one comparing sclerotherapy with portacaval shunt after failed medical treatment showed that failure to control bleeding was higher with sclerotherapy. Rebleeding, assessed in three trials, was also significantly higher with injection sclerotherapy. Nonetheless, no significant differences in mortality were found.

Although emergency liver transplantation has been advocated, it is best performed after initial control of variceal bleeding, preferably using an endoscopic technique, as this will interfere least with a subsequent transplant. For the failures of endoscopic therapy in potential transplant recipients, a TIPS shunt may be used as a bridge to transplantation.

Patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding and end-stage liver disease, deteriorating renal function requiring inotropic support, and on ventilation and those who do not respond to emergency treatment should be considered for conservative treatment only. While this decision poses difficult moral and ethical issues, patients with a high MELD score and a Child–Pugh score over 13 seldom survive despite heroic efforts.

Long-Term Management After Variceal Bleeding

Evaluation of Liver Function

Once the acute bleeding episode has been controlled and the patient is stabilized, a detailed evaluation is undertaken to identify the cause of the portal hypertension, the severity of any underlying liver disease, and the likely natural history. The comprehensive medical assessment includes documentation of clinical and biochemical factors that might influence variceal rebleeding, liver function, and prognosis. A detailed history is obtained regarding current and previous bleeding episodes, the duration and amount of alcohol intake, family history of liver disease, and previous exposure to viral hepatitis. The physical examination should document the presence of stigmata of chronic liver disease including jaundice, peripheral and sacral edema, spider angiomata, gynecomastia, palmar erythema, testicular atrophy, Dupuytren’s contractures, clubbing, fetor hepaticus, flapping tremor, cutaneous purpura, and petechiae. Abdominal examination should note the presence of a firm or nodular liver, splenomegaly, ascites, caput medusa and the Cruveilhier–Baumgarten syndrome with a paraxiphoid venous hum due to retrograde flow in a patent umbilical vein. Clinical examination, in addition, seeks to establish clinical evidence of encephalopathy with asterixis and cognitive dysfunction.

All patients require full laboratory studies including hematologic, biochemical, and specific serologic testing. Patients’ fluid and electrolyte status is evaluated by measuring serum electrolytes, urea, and creatinine. Standard biochemical tests of liver dysfunction include serum albumin, bilirubin, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT, and alpha-fetoprotein levels. All patients should have hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-HBc core antigens tested. Hepatitis C is assessed by antibodies to HCV using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with positive results confirmed by recombinant immunoblot assay. Patients without an evident cause of cirrhosis are screened for hemochromatosis including serum ferritin and transferrin saturation levels, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, and Wilson’s disease. Autoimmune hepatitis is tested by antinuclear and smooth muscle antibodies and serum IgG levels. In selected patients in whom the diagnosis is unclear, an ultrasound-guided plugged or transjugular liver biopsy can be done and transjugular portal wedge pressures measured. Transcutaneous abdominal ultrasound is performed to assess liver size and appearance including the features of steatosis, cirrhosis, atrophy–hypertrophy complex, portal vein patency and diameter, direction of portal vein flow, spleen size, and duplex Doppler assessment of portal flow velocity.

Although the risks of recurrent variceal bleeding diminish with time, up to 70% of patients will have further variceal bleeding if left untreated. For this reason, all patients who have had a variceal bleed should be considered for long-term management aimed at preventing further variceal bleeds.

Endoscopic therapy is the primary treatment of choice. The options and second line alternatives are summarized in Table 4 and are detailed below.

Endoscopic therapy is the primary treatment of choice. The options and second line alternatives are summarized in Table 4 and are detailed below.

Table 4 Long-Term Management Options to Prevent Variceal Rebleeding | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Injection Sclerotherapy

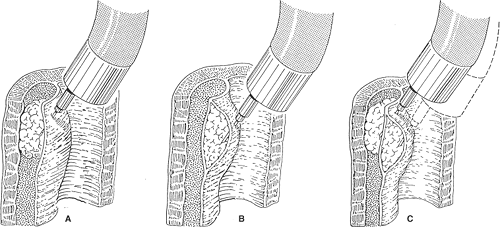

In the past, injection sclerotherapy was the most widely used endoscopic treatment. Sclerotherapy has now been replaced by endoscopic variceal ligation as the first-line endoscopic therapy. Sclerotherapy, when used, is performed using a video endoscope and a freehand injection technique. Unlike most other forms of therapy used in the management of esophageal varices, sclerotherapy techniques are less standardized. The injections may be placed directly into the varices (“intravariceal”) with the objective of thrombosing the varices, or into the submucosa adjacent to the varices (“paravariceal”) to produce submucosal edema to stop acute variceal bleeding and to cause thickening of the mucosa to prevent later bleeding. Many endoscopists use a combination of these two techniques (Fig. 3).

Sclerotherapy is performed with different skill levels and protocols and variable frequencies of injections and endoscopic review. It is not surprising that controlled trials comparing sclerotherapy with other specific therapies, including variceal ligation, have yielded conflicting results. We prefer a combined para- and intravariceal technique for acute variceal bleeding and favor a predominantly intravariceal technique for long-term management when varices are smaller. Our sclerosant of choice is 5% ethanolamine oleate. Injection treatments are continued at weekly intervals until the varices have been eradicated and are no longer visible during endoscopic surveillance. Thereafter, the patient is assessed at 3 months and then at 6-monthly and subsequently at yearly intervals. Whenever recurrent varices are diagnosed, a repeat course of weekly sclerotherapy is undertaken until re-eradication is achieved.

Esophageal Variceal Ligation

The use of endoscopic band ligation represents a seminal development in the endoscopic treatment of varices. The concept of endoscopic variceal ligation is similar to the technique used for treating hemorrhoids, and was devised by Stiegmann from Denver, Colorado. Hemostasis is achieved by physical constriction of the base of the varix by a rubber band. Ischemic necrosis of the strangulated mucosa and submucosa trapped within the band occurs, followed by sloughing of the banded varix. The resulting shallow mucosal ulcer re-epithelializes over the next 14 to 21 days, with scarring and shrinkage of the residual varix by maturing fibrous tissue. Two different types of ligating devices are used: (a) the initial single-band delivery system and (b) the newer multiband ligator. The original Stiegmann apparatus allowed the placement of one variceal band at a time and required the use of an overtube to allow multiple withdrawals and reinsertions of the endoscope. The newer multiband apparatus allows the sequential placement of 8 to 10 bands during a single insertion of the endoscope, obviating the need for an overtube. The multiband variceal ligator has replaced the single-shot banding equipment in most endoscopy units. The band ligation procedure is repeated at weekly intervals until all the varices are obliterated.

Fig. 3. Technical variants of injection Sclerotherapy A: Intravariceal injection. B: Paravariceal or submucosal injection. C: Combined intravariceal and paravariceal injections. |

Endoscopic variceal ligation has been shown to be at least as effective as injection sclerotherapy in the emergency management of bleeding esophageal varices. Furthermore, variceal eradication using ligation requires fewer endoscopic treatment sessions, and causes substantially less local esophageal complications. Current data demonstrate a clear advantage for ligation in preference to sclerotherapy in elective variceal treatment. Ligation is now regarded

as the endoscopic treatment of choice in the management of all esophageal varices.

as the endoscopic treatment of choice in the management of all esophageal varices.

Alternative Long-Term Management Options

Although we prefer endoscopic therapy as the primary therapy for most patients, pharmacological therapy with propranolol alone or in combination with nitrates is an acceptable alternative primary long-term therapy in selected patients.

Pharmacological Therapy

The use of beta-blockers as primary long-term therapy has considerable support in the current literature. Several meta-analyses have concluded that beta-blockers, principally propranolol, significantly reduce the incidence of recurrent bleeding and improve long-term survival when compared with placebo. Unfortunately, beta-blockade is not without its drawbacks. There are a number of relative contraindications to beta-blockade, including bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, congestive cardiac failure, and unstable insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Once treatment is initiated, beta-blocker–induced side effects may also be a problem. The most common side effects are loss of energy, depression, impotence, and headaches. In a minority of patients, these side effects may be sufficiently severe to cause discontinuation of treatment. Thus, a significant proportion of the population at risk may be unsuitable for treatment with beta-blockers or may stop taking the drug as a result of side effects. In addition, one-third of patients treated with standard doses of beta-blockers do not achieve significant reduction in portal venous pressures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree