Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an endoscopic technique whereby a specialized side-viewing upper endoscope (duodenoscope) is passed through the mouth to the major papilla in the second portion of the duodenum.

Using various instruments through the working channel of the duodenoscope, access can be gained into the bile and pancreatic ducts and a variety of complex interventions can be performed. The ducts are usually visualized with x-ray after injection of a contrast medium into the ducts. Alternatively, direct visualization of the ducts is also possible via smaller scopes usually passed through the working channel of the duodenoscope or directly into the ducts without use of the duodenoscope.

ERCP allows for minimally invasive management of pancreatic and biliary disorders, but it can be a challenging technique to learn and has higher potential for complications than other standard endoscopic procedures.

Prior to ERCP, a thorough patient history and physical exam should be performed to select appropriate laboratory and imaging studies for workup. These preprocedural studies will enable the proper selection of patients to benefit most from ERCP. A careful history of pancreatic and biliary symptoms and previous endoscopic and surgical therapy of the biliary tree or pancreas is essential. In addition, previous intestinal surgery may make ERCP technically difficult or impossible (such as a previous Roux-en-Y gastric bypass). Finally, complicating medical conditions can be elicited, which might impact the safety of anesthesia or increase the risk of complications of ERCP (such as anticoagulation).

ERCP is indicated for patients with a variety of biliary tract and pancreatic disorders.1 For patients with such disorders, specific symptoms may include abdominal pain (location, character, frequency, duration, alleviating and exacerbating factors), nausea and vomiting, jaundice, change in color of stools and urine, pruritus, steatorrhea, weight loss, and hyper or hypoglycemia. Physical exam should evaluate for jaundice, detailed abdominal exam, and signs of malnutrition or cachexia, which may suggest underlying chronic disease or malignancy.

Key aspects of social history include tobacco use and alcohol. In those patients with suspected malignancy, it is important to elicit any family history of similar malignancies.

Specific laboratory work obtained to decide the need for ERCP usually includes liver enzymes (transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, direct and indirect bilirubin) and pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase). In suspected malignancy, certain tumor markers such as carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and α-fetoprotein (AFP) may be obtained as deemed appropriate. Typically, coagulation parameters (platelets, prothrombin time [PT], international normalized ratio [INR], and partial thromboplastin time [PTT]) are not obtained unless the patient is on anticoagulation or history suggests coagulopathy.

Imaging studies for suspected biliary and pancreatic disease may include transabdominal ultrasound; high-quality, crosssectional imaging such as abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan; or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Transabdominal ultrasound is typically not adequate for accurate visualization of the entire pancreas. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), however, can provide valuable information about pancreatic ductal and parenchymal anatomy and biliary anatomy for proper selection of patients for ERCP.

ERCP has evolved from a diagnostic to an almost exclusively therapeutic procedure.1 Imaging studies that have been described in the previous section (transabdominal ultrasound, CT, MRI/MRCP, intraoperative cholangiography, EUS) should provide diagnostic information for proper selection of patients requiring therapeutic ERCP. In general, a careful assessment of pancreatic ductal and biliary anatomy by one of these techniques is required prior to considering ERCP. ERCP should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes only, as the risk of ERCP outweighs the benefit in this circumstance.

ERCP is not indicated in the evaluation of abdominal pain of obscure origin in the absence of other objective findings suggesting biliary tract or pancreatic disease.1

ERCP is indicated in patients with various pancreaticobiliary disorders. Specific biliary indications include therapy for choledocholithiasis, management of benign and malignant biliary strictures (including tissue sampling, stricture dilation, stenting), and evaluation and treatment of bile leaks.1

Pancreatic diseases that can be evaluated and treated with ERCP include recurrent acute pancreatitis, management of pain in chronic pancreatitis patients with obstruction of pancreatic duct due to stones and/or strictures, pancreatic duct leaks, drainage of fluid collections that communicate with the pancreatic duct, and pancreatic cancer causing pancreatic duct and/or bile duct obstruction.1

Other specific conditions that can be evaluated and treated with ERCP include ampullary stenosis, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), type III biliary cysts (choledochocele), pancreas divisum causing recurrent acute pancreatitis, and treatment of ampullary cancers and adenomas.1

Table 1 outlines indications for therapeutic ERCP.

Table 1: Indications for Therapeutic Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Biliary

Choledocholithiasis

– High preoperative probability

– Intraoperatively diagnosed

– Definitive diagnosis prior to surgery

Strictures

– Benign

– Malignant

Postoperative bile leaks

Choledochocele (type III biliary cyst)

Biliary sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

– Type I

– Type II

Pancreatic

Chronic pancreatitis

– Stricture

– Stones

– Both

Pancreatic duct disruption

Transpapillary pseudocyst drainage

Strictures

– Benign

– Malignant

Acute pancreatitis

– Acute biliary pancreatitis

– Recurrent acute pancreatitis

– Pancreas divisum causing recurrent acute pancreatitis

Pancreatic sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

– Type I

– Type II

Other

Ampullary cancer or adenoma

From Pannu DS, Draganov PV. Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and instrumentation. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):401-416.

ERCP is usually performed as an outpatient procedure, but postprocedural observation may be prolonged due to the potential complexity of the procedure as compared to other standard endoscopic procedures.

Prior to initiation of the procedure, the endoscopist should be absolutely certain of the indication of the procedure taking into account all of the preprocedural workup. The importance of having a well-defined therapeutic goal for the procedure cannot be overemphasized. ERCP should not be performed for diagnostic purposes only.

Informed consent should be obtained, explaining all the potential benefits, risks, and alternatives. This should include a discussion of the risk to that individual patient, taking into account the patient and procedural factors which influence the rate of postprocedure complications.

Table 2 details risk factors for overall complications of ERCP.

Table 2: Risk Factors for Overall Complications of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Definite

Possible

No

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Young age

Comorbid illness

Cirrhosis

Pancreatic contrast injection

Small diameter CBD

Difficult cannulation

Failed biliary drainage

Female sex

Precut sphincterotomy

Trainee involvement

Billroth II anatomy

Lower case volume

Periampullary diverticulum

Percutaneous biliary access

CBD, common bile duct.

From Freeman ML. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: avoidance and management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):567-586.

Patients are kept NPO overnight prior to the procedure. Antibiotics with broad-spectrum coverage should be considered periprocedurally in only limited circumstances of biliary ductal obstruction or transpapillary pancreatic pseudocyst drainage.

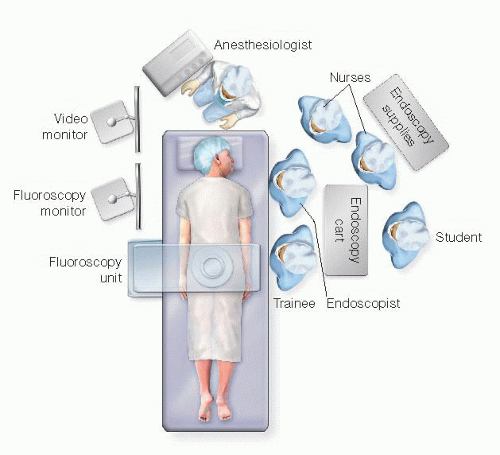

The patient lies in a left semiprone position on the fluoroscopy table with both arms at their side. The right chest/shoulder is usually propped up slightly so that the head faces the endoscopist (FIG 1). A plain radiograph (scout film) is usually taken to ensure the field is clear of any radiopaque material such as monitoring wires and to document the presence/absence of any devices such as drains, stents, feeding tubes, and so forth.

Sedation can be either conscious sedation (combination of benzodiazepine and opiate) administered under the supervision of the endoscopist or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). Most units now use either MAC or general anesthesia, depending on patient and case specifics.

Depending on the indications, various maneuvers may be performed during ERCP. However, passage of the scope to the major papilla in the duodenum and selective cannulation of the desired duct is essential to every successful ERCP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree