Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Barrett Neoplasia

Shajan Peter

C. Mel Wilcox

Klaus Mönkemüller

DEFINITION

Barrett esophagus (BE) is a strong risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.1

The traditional treatment of choice for “resectable” esophageal adenocarcinoma is esophagectomy.

However, surgical resection is still associated with significant mortality and morbidity, even in high-volume centers and especially in elderly or poor surgical candidates.3

Thus, during the last two decades, patients with early cancer or those with high-grade dysplasia have been successfully treated with endoscopic resection methods.4,5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of mucosal neoplasia of the distal esophagus is narrow. The most common malignant neoplasia of the distal esophagus is adenocarcinoma, followed by squamous cell cancer.4,5

Proximal stomach cancer such as cardiac or fundic adenocarcinoma extending into the esophagus may be difficult to differentiate from distal esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Submucosal tumors such as gastrointestinal (GI) tumors, spindle cell tumors, lipoma, and leiomyoma are easily differentiated from mucosal lesions as these tumors generally have a normal overlying mucosa.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Most patients with Barrett’s neoplasia do not have any specific symptoms and BE is discovered incidentally during an upper GI endoscopy performed for the evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, dyspepsia, or abdominal pain.6

However, Barrett’s neoplasia is more common in patients with the following characteristics: male, central obesity, Caucasian, age older than 50 years, tobacco use, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).6

Although reflux of acid is a common occurrence in BE, a high proportion of BE patients deny a history of reflux symptoms.7

Therefore, any patient undergoing upper endoscopy should be carefully investigated for columnar-lined epithelium and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus, with special attention to patients with the risk factors mentioned earlier.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiologic studies do not play a role in the evaluation of BE unless there is a stricture present (benign or malignant). In this instance, a barium esophagogram can be helpful to determine the length and characteristics of the stenosis.

Although computed axial tomography is useful to evaluate for lung metastasis and mediastinal and perigastric lymph node involvement in esophageal adenocarcinoma, its role in patients with early Barrett neoplasia is negligible, as most of these patients have local disease, which does not extend beyond the submucosa of the esophagus.

Patients with Barrett’s cancer invading the submucosa (sm1) have a very low risk of lymph node metastasis and thus are ideal candidates for EMR.4, 5, 6

In the past, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was used to determine the depth of GI layers involvement in early Barrett neoplasia.8

However, the sensitivity and specificity of EUS for early Barrett neoplasia are low and the results can be misleading.8

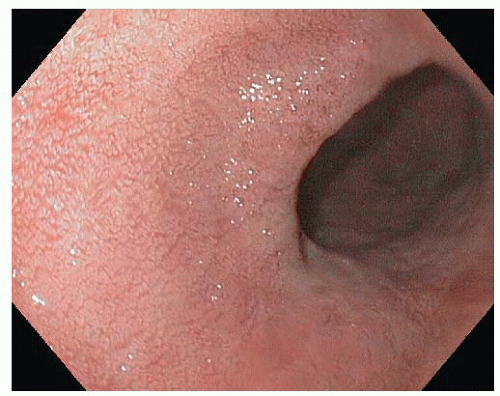

The mainstay of diagnosis of BE is with light endoscopy, ideally using high-definition endoscopes and equipment.9

It is very important to measure the proximal distance of extension of cylindrical-type epithelium into the esophagus. The extent of BE segment should be defined using the Prague C & M classification including the length of the circumferential segment (C) and the maximal extent of the BE segment (M).10

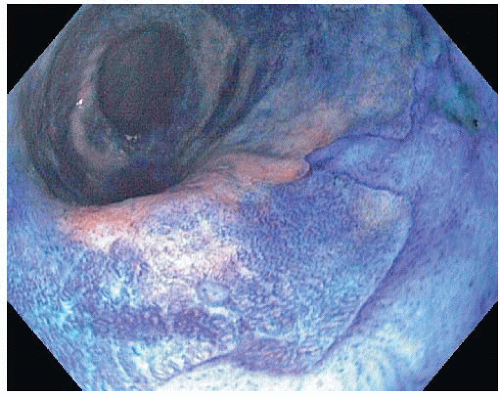

The use of various staining agents and dyes (chromoendoscopy) such as methylene blue (FIG 1) and indigo carmine or agents such as acetic acid (FIG 2) enhances the mucosal pit pattern analysis (see the following text) and thus facilitates the detection high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma.9

Other imaging modalities that might help in delineating BE are narrow band imaging (NBI) (FIG 3), autofluorescence imaging, and confocal laser endoscopy.

Magnification endoscopy is also important to characterize the mucosal surface and pit pattern (FIG 4).

The most widespread classification used to categorize the pit pattern in BE is the Endo classification (adapted from S. E. Kudo).11

This classification categorizes the opening of the pits into round (I), stellar or asteroid (II) (see FIG 2), tubular elongated (IIIL), tubular short or round (IIIS) (see FIG 1), gyrus or sulcus branched (IV) (see FIG 4), and irregular or amorphous (V) (FIG 5).

Types I, II, and III pit patterns are “benign,” whereas pit pattern types IV and V are more commonly present in advanced neoplasia or carcinoma.

Chromoendoscopy is performed to aid in obtaining directed (i.e., targeted) biopsies prior to mucosectomy to define the precise extent of neoplastic involvement.

Targeted biopsies are obtained from visible abnormalities, followed by four-quadrant biopsies of every 1 to 2 cm of the BE segment (Seattle protocol; see Part 1, Chapter 27) and these should be reviewed by a dedicated GI pathologist.

FIG 2 • Acetic acid is another useful adjunct to define the mucosal pit pattern. Careful analysis of the pit pattern of Barrett’s epithelium is mandatory to define its type and discover areas of dysplastic cells. This sample shows a type II pit pattern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|