22.1 INTRODUCTION TO EMERGING VIRUSES

The term “emerging virus” is used in a number of contexts: it may refer to a virus that has recently made its presence felt by infecting a new host species, by appearing in a new area of the world, or by both. Sometimes a virus is described as a “re-emerging virus” if it has started to become more common after it was becoming rare. Foot and mouth disease virus (Section 14.2.5) re-emerges in the UK from time to time.

Human activities may increase the likelihood of virus emergence and re-emergence. Travel and trade provide opportunities for viruses to spread to new areas of the planet, and the introduction of animal species into new areas (e.g., horses into Australia) may provide new hosts for viruses in those areas.

Other activities that may result in virus emergence involve close contact with animals, including the hunting and killing of non-human primates for bushmeat. It has been shown that viruses such as simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) can be present in the meat and there is a risk of acquiring an infection when the meat is handled. Simian-to-human transmission of SIVs is thought to have occurred several times, resulting in the major groups of HIV-1 and HIV-2 (Figure 21.4), and there is concern that further viruses might emerge as a result of contact with bushmeat.

If a virus jumps into a new host species it may undergo some evolutionary changes in the new host, resulting in a new virus. This is how HIV-1 and HIV-2 were derived from simian immunodeficiency viruses, and how a new canine parvovirus was derived from feline panleukopenia virus (Section 21.3.4). Other new viruses emerge when recombination and reassortment result in new viable combinations of genes (Section 21.3.3); new strains of influenza A virus come into this category. Some “new” viruses that are reported are actually old viruses, about which mankind has recently become aware, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (Chapters 11 and 23).

This chapter considers examples of viruses that have “emerged” and “re-emerged” in the late twentieth century and the twenty-first century. Most of the examples discussed are human viruses.

22.2 VIRUSES IN NEW HOST SPECIES

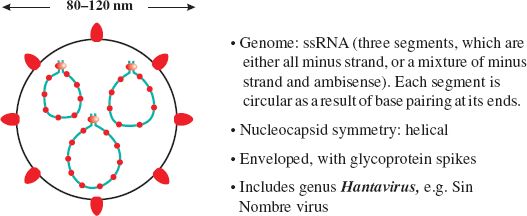

22.2.1 Bunyaviruses

In 1993 in a region of the south-western USA known as Four Corners, some residents became afflicted by an illness resembling influenza; many of them developed severe lung disease and died. The region is normally very dry, but there had been unusually high rainfall and snowfall that had resulted in a burst of plant growth, followed by explosions in the populations of small mammals. One of those mammals was the deer mouse, a species that is attracted to human habitation.

On investigation, it was found that many of the deer mice were persistently infected with a virus that was excreted in their urine, droppings, and saliva. Humans exposed to these materials were becoming infected and developing the respiratory illness. The virus was characterized as a new hantavirus and the disease was called hantavirus pulmonary syndrome.

Hantaviruses are members of the family Bunyaviridae (Figure 22.1). They are named after the River Hantaan in Korea, where the first of these viruses was isolated during the Korean War from soldiers who had developed hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Similar viruses are known elsewhere in Asia and in Europe.

There was much heated debate about naming the virus that had appeared in Four Corners. Local people did not want it named after a place as they did not want potential tourists to be discouraged by publicity surrounding a virus disease. Eventually the Spanish name Sin Nombre virus (the virus without a name) was agreed.

Since 1993 hantavirus pulmonary syndrome has been reported in many parts of North and South America, with mortality rates of around 40%. Some of these cases have been caused by Sin Nombre virus, while many others have been caused by newly described hantaviruses, such as Andes virus. The normal hosts of all these viruses are rodents, in which the viruses can establish persistent infections.

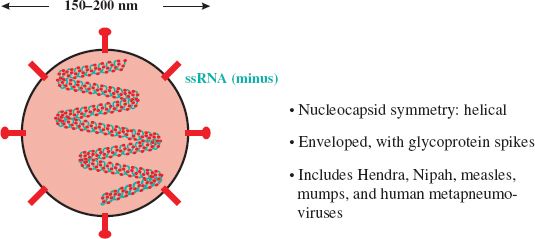

22.2.2 Paramyxoviruses

22.2.2.a Hendra virus

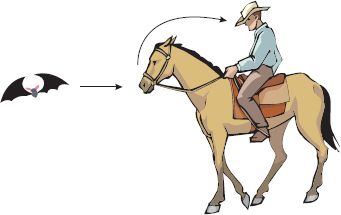

In 1994 at Hendra in south-east Australia, there was an outbreak of pneumonia in horses, then a trainer and a stable hand who worked with the horses developed severe respiratory disease. The horses and the two humans were found to be infected with a virus that had characteristics of the family Paramyxoviridae (Figure 22.2). This family contains well-known viruses such as measles and mumps viruses, but the virus that was isolated was previously unknown. Thirteen of the horses and the trainer died as a result of infection with the virus, which was named Hendra virus.

A couple of years later a man living about 800 km north of Hendra developed seizures and paralysis. He was found to be infected with Hendra virus and he died from meningoencephalitis. It turned out that he had helped with post mortems of two horses 13 months earlier. Tissue from the horses had been preserved and when it was examined it was found to contain Hendra virus.

It looked as though the infected humans had acquired the virus from horses, but the source of infection for horses was a mystery. An investigation was initiated, and evidence was obtained that the virus is present in populations of fruit-eating bats; Hendra virus-specific antibodies were found in all four local species of the bat genus Pteropus, and infectious virus was isolated from one bat. Bats appear to be the normal hosts of Hendra virus, and experimental infection of several bat species has provided no evidence that infection causes disease in these animals. It appears that occasional transmission to horses occurs, with very occasional transmission from horses to humans (Figure 22.3). In horses and humans the outcome of infection is very different, with the virus demonstrating a high degree of virulence.

There have been further cases of Hendra virus disease in horses and humans in eastern Australia; many of these cases were fatal.

22.2.2.b Nipah virus

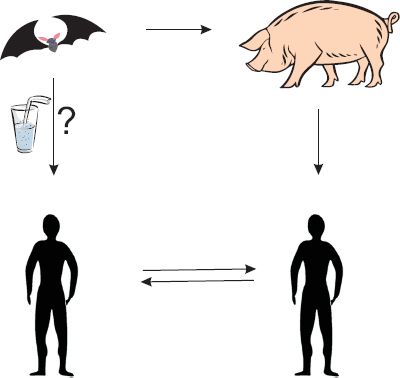

In Malaysia, in 1997, there appeared a new disease of pigs, characterized by respiratory disease and encephalitis. Soon afterwards workers on the affected pig farms began to develop encephalitis; over a two-year period there were several hundred human cases, with over 100 deaths. In 1999 a new virus was isolated from the brain of one of the patients who had died. The virus turned out to be a paramyxovirus with similar characteristics to Hendra virus (Figure 22.2) and it was named Nipah virus. In an attempt to contain the outbreak over one million pigs were slaughtered.

A search was initiated to find the reservoir of infection. As with Hendra virus, bats were investigated and evidence of Nipah virus infection was found in fruit-eating bats of the genus Pteropus. Infectious virus was isolated from bats’ urine and virus-specific antibodies were found in their blood. Thus the situation parallels that of Hendra virus, with a reservoir of infection in bats and transmission to humans via an intermediate mammalian host (Figure 22.4).

Figure 22.4 Nipah virus transmission routes. The virus can be transmitted from bat to pig, pig to human, and human to human. Bat-to-human transmission may also occur.

More recently, in Bangladesh and India, there have been outbreaks of Nipah virus encephalitis and respiratory disease in humans; many of the cases have been fatal. In these outbreaks there was no evidence of transmission from pigs. It is believed that the virus was transmitted from bats to humans; for example, as a result of humans drinking date palm sap contaminated by bats during its collection. There is also evidence of human-to-human transmission of the virus.

22.3 VIRUSES IN NEW AREAS

22.3.1 West Nile virus

In 1999 some people in New York became ill with apparent viral encephalitis; several of them died. At about the same time several birds in the zoo became ill, and deaths of wild birds, especially crows, were reported. Diagnostic tests revealed that the human patients and the birds were infected with West Nile virus (WNV).

This virus has been known since 1937 when it was first isolated from the blood of a woman in the West Nile region of Uganda. In addition to Africa, the virus is also known in Eastern Europe, West Asia, and the Middle East, but until 1999 it had never been reported in North America.

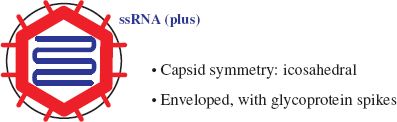

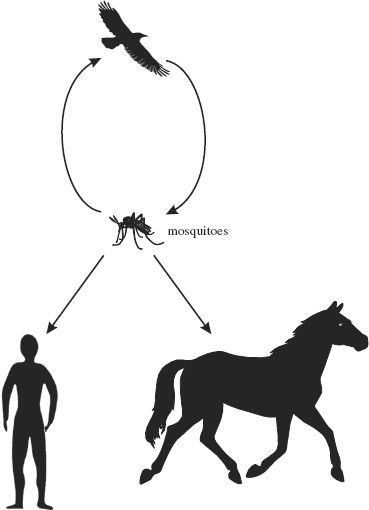

WNV is classified in the family Flaviviridae (Figure 22.5). The virus has a wide host range. It cycles between birds and mosquitoes, in which it replicates. Infected mosquitoes can transmit the virus to mammalian species, including humans and horses (Figure 22.6). Mammalian infections are normally dead-end as far as the virus is concerned (i.e., the virus is not normally transmitted on to new hosts).

Figure 22.5 Families Flaviviridae and Togaviridae. Flaviviruses and togaviruses have many properties in common, but flaviviruses (around 50 nm diameter) are smaller than togaviruses (70 nm diameter).

Figure 22.6 West Nile virus transmission routes. The virus cycles between birds and mosquitoes. Sometimes infected mosquitoes transmit the virus to mammals, including humans and horses.

Most infections with WNV are asymptomatic, but about 25% of human infections result in signs and symptoms such as fever and aching muscles. Less than 1% of infections spread to the central nervous system, causing severe illness (such as encephalitis), which may result in death; these cases are mainly in patients over 60 years old. Protective measures for humans include use of insect repellents, wearing “mosquito jackets” and treating mosquito breeding areas with insecticides.

It is not known how WNV was introduced into North America, but once there it spread rapidly throughout the US (Figure 22.7). Within five years it was also present in Canada, Central America, and the Caribbean islands; it is now present in South America. The virus has caused hundreds of human deaths in North America.

Figure 22.7 Approximate distribution of West Nile virus in the Americas 1999–2004.

Source: Mackenzie et al. (2004) Nature Medicine, 10, S98. Reproduced by permission of Nature Publishing Group and the author.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree