LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To provide an overview of educational theories and best practices that can be leveraged to create a comprehensive educational program in professionalism.

To describe elements of a formal curriculum for teaching professionalism.

To explain the relationship between the formal and informal curriculum within professionalism education.

To analyze the primary components of the informal curriculum related to professionalism.

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Fraser, a senior faculty member, was frustrated by his latest teaching assignment. For years he has taught clinical skills to medical students in small group sessions, but this year they added on a module on professionalism, which all preceptors were required to teach. It includes definitions of professionalism along with expected behaviors for students. Dr. Fraser felt that these did not belong in a “skills” workshop, because, in his view, “You can’t teach this stuff—students will either be professional or they won’t. Besides, they should already know how to behave appropriately, by watching their attending physicians and residents.”

Dr. Fraser does not consider professionalism a competency or skill that can be learned—rather, he thinks of it as a trait that one possesses (or fails to possess). The evidence does not support this view, and one goal of this book is to demonstrate that if professionalism is properly viewed as a competency, it follows that it can be taught, learned, and developed over time. Dr. Fraser also mistakenly assumes that professionalism is easily learned by watching more senior physicians. This is partly true, in that excellent positive (and unfortunate negative) role models can certainly imprint on learners and affect their behavior. But it is also clear that relying on passive observation is insufficient at best, and potentially harmful at worst (also see Chapter 8, The Hidden Curriculum and Professionalism).

Of interest, there is some suggestion that students are also unhappy with current educational approaches to professionalism. One school reported on their experience in teaching professionalism and found that a large portion of students felt the word professionalism itself was overused, and that the course content felt like “a collection of excessive directives, lectures, rules, and moral pronouncements that they found repetitive and patronizing” (Goldstein et al, 2006). Some educators focus heavily on evaluation and espouse a zero tolerance policy for transgressions. This leads students to be fearful of admitting difficulty. Students also frequently describe a disconnect between lessons learned in the classroom and lessons based on (and behavior modeled in) the clinical environment. This can be disorienting and confusing, and may lead to cynicism and a sense of futility (e.g., why learn about it if it doesn’t occur in practice?). Another reason for the backlash is that professionalism is often taught in a negative manner, focusing on “lapses” and when things go wrong—medical errors, disruptive physicians, impairment, intimidation and harassment, andso on. This may set students up to expect the worst rather than the best from their preceptors and colleagues. It also may carry the presumption that everyone is susceptible to displaying unprofessional behavior. Although this may in fact be true, it is disquieting to young students, who can’t imagine that doctors can be anything but exemplars of altruism, compassion, and excellence.

A comprehensive overview of educational strategies relevant to professionalism is beyond the scope of this book. In this chapter, we provide an overview of educational theories and best practices that can be leveraged to create a comprehensive educational program in professionalism. Although the literature suggests that there is no one best single approach to teaching professionalism, there are a number of emerging strategies based on accepted pedagogy that can help educators develop and implement a strong program in professionalism. Dominant themes identified in a recent Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) review included the importance of selecting students with well-developed capacity for humanism, attending to their moral development, including professionalism as a major theme through the formal medical education process, using experiential learning supported by guided critical reflection as a best practice, and optimizing the culture and values of the institutions in which education occurs (Birden, Glass, & Wilson, 2013).

EDUCATIONAL THEORIES THAT CAN GUIDE OUR WORK

Being an outstanding physician is a complex task. Not only are physicians expected to sustain their mastery of a conceptually difficult body of knowledge and to behave in a manner that is compatible with the tenets of professionalism, but they are expected to be able to demonstrate these abilities while interacting with an increasingly diverse set of patients in a very dynamic healthcare delivery environment. Given the complexity of the tasks in front of physicians, it is not surprising that teaching professionalism as a set of inviolate rules has not been a successful educational strategy. As Huddle (2005) describes, teaching professionalism requires strategies that bring about “a personal transformation—the shaping of the moral identity of the learner.” Achieving this transformation requires more than just a will to behave professionally. It requires knowledge, attitudes, judgment, and skills. Physicians and physicians in training need to know the values of professionalism, they need to commit(or profess) to following those values, they need judgment to understand the complexity of the situations in which professionalism must be lived, and they must have skills to apply their knowledge, attitudes, and judgment in the sometimes chaotic real world of medicine. Cooke, O’Brien, and Irby (2011) as well as others (Cruess & Cruess, 2009) have argued for the explicit teaching of professionalism and professional identity formation.

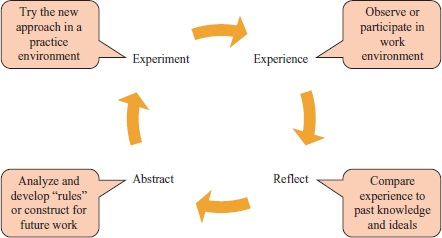

Educational theories that describe how young doctors learn and how expertise develops underpin the most successful strategies in educating for professionalism (Yardley, Teunissen, & Dornan, 2012). Piaget’s (1985) constructivist theory states that we “construct” new learning during the intersection of ideas with experience. New experiences are either assimilated or adapted to fit our current schemas. Kolb (1984) further refines this thought by describing a cycle of learning in which a learner participates in an experience, reflects on that experience, works to develop abstract rules they can use in future situations, and then plans to experiment with these rules before repeating the experience again. This cycle of learning (Figure 9-1) is launched when the learner, comparing his or her current experience to past experiences, realizes that something is different.

Mezirow (2009) has called this the “disorienting dilemma,” wherein something is amiss and the learner will seek to understand the differences and decide whether his or her existing approach should be changed based on this new experience. Experts in the education of adults and professionals realize that the experiences most likely to result in these high-impact disorienting dilemmas occur in the workplace and then only if the student is engaged in work that they, and the others in the environment, view as authentic and valued—this is referred to as “legitimate peripheral participation” (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Learning lessons in the workplace requires the skilled guidance of workplace professionals with more experience than the learner in question. This learning is thought to occur best in the “zone of proximal development,” which is described by Vygotsky (1978) as the difference between what a learner can do with assistance and what they can do alone. In the zone of proximal development, the learner is encouraged to practice skills beyond their current capability with support from experts within the workplace. In a process known as scaffolding, faculty initially provide substantial support and then gradually withdraw that support and guidance as the learner demonstrates greater proficiency with their assigned work. Table 9-1 summarizes important educational theories that guide the construction of a professional curriculum.

| Piaget | Constructivist theory | Learning is constructed at the intersection of new ideas with the mental models (schema) formed from past experience. |

| Kolb | Experiential learning | Learning progresses through a cycle of adaptive learning; experience is followed by reflection, then abstraction, then experimentation. |

| Knowles | Adult learning theory | Adults bring past experience to learning and learn best when they participate in selection of learning goals, see immediate relevance in lessons, and are engaged in problem solving activities. |

| Mezirow | Transformative learning | Learning and transformation occur when learners experience disorienting dilemmas that suggest their past knowledge is inadequate and then work to construct new mental models. |

| Lave and Wenger | Situated learning theory | Learning occurs when learners are engage in legitimate peripheral participation in the workplace communities of practice. |

| Vygotsky | Socio-cultural learning theory | The zone of proximal development is the difference between what a learner can do independently and what a learner can do with the assistance of more experienced members of the community or practice. |

| Dreyfus & Dreyfus | Model of skill acquisition | Learners develop skills in a predictable sequence, starting with learning context-free rules and culminating in practical wisdom that allows them to function in almost any context. |

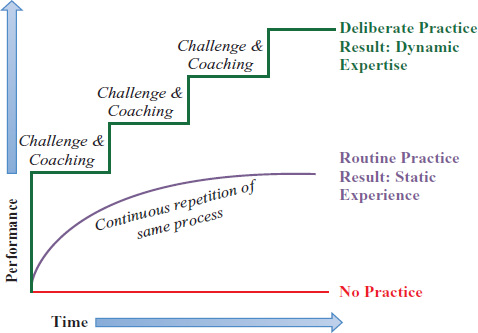

| Ericsson | Development of expertise | The development of expertise, as opposed to experience, requires deliberate practice with coaching. |

Educational theorists who study the development of expertise reinforce the importance of authentic workplace experience. The foundational work of Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1980) on the stages of skill acquisition is highly relevant to the work of educating for professionalism (Batalden et al, 2002). Medical students are novices, capable of reciting the “rules” of professionalism (be altruistic, be respectful, be honest), yet they may stumble when asked to apply these values in a busy clinical environment. Interns and residents are capable of performance described as competent. They are able to apply standard rules in standard circumstances but may struggle with complex or novel situations. Proficiency is a more advanced level of performance, found in residents and practicing physicians early in their careers. The proficient physician is able to view every situation holistically and to balance multiple competing demands. When proficient physicians recognize a professionalism problem, they can craft a work-around that generally fits the situations at hand. Expert performance is developed only after extensive experience. At this level, the physician acts instinctively and correctly in a wide variety of circumstances, drawing on vast stores of experientially acquired knowledge and skills. Many call this intuitive performance phronesis, or practical wisdom. Ericsson (2004) has added an important construct to the work of Dreyfus and Dreyfus. He recognized that routine practice, described as simply doing the same activity over and over, does not help one develop skills to master new circumstances. To successfully navigate the Dreyfus stages of skill acquisition, physicians and physicians in training must engage in deliberate practice, meaning they should be encouraged to take on increasingly complex challenges in the workplace with direct observation, debriefing, and coaching by a more expert individual (Figure 9-2).

Putting these theories into action means that professionalism education cannot end in the classroom and it cannot be left to chance in the clinical environment. In an ideal approach to learning professionalism, learners at all stages need to be prepared to participate in authentic workplace experiences using classroom and simulated activities and then be assigned to work in the patient care environment under the guidance of expert clinical faculty. The faculty must be prepared to welcome the learner into the clinical community of practice, offer authentic but developmentally appropriate roles in that community, provide role modeling and supervision with coaching, and guide critical reflection of the inevitable disquieting dilemmas learners will experience.

DEVELOPING A FORMAL CURRICULUM FOR PROFESSIONALISM

The formal curriculum describes what faculty believe the students need to learn, methods they will use to help students learn, and tools and strategies faculty will employ to assess the learner and evaluate the curriculum. Like any other curriculum, the development of a formal professionalism curriculum must proceed in a structured way, using a model such as Kern’s (2009) six-step model for curriculum. Unlike other curricula that focus on discrete biomedical science disciplines, formal curricula in professionalism are highly affected by the culture and the climate of the educational and clinical arena in which learners learn. The informal curriculum, including teaching that occurs outside in a variety of settings (i.e., ward rounds, bedside, and so on) that are unscripted and predominantly ad hoc, and the hidden curriculum, including lessons that are learned, but are not explicitly intended or embedded in the organizational structure and culture, can either reinforce or negate the impact of the formal curriculum. Experts in professionalism education have outlined a set of principles that must be addressed to ensure that the formal, informal, and hidden curricula are all aligned and synergistic in their impact on learners (Table 9-2). Chapter 12, Organizational Professionalism, illustrates examples of institutions that have worked to ensure that their institutional values resonate with the professionalism curriculum.

| Curricular element | Guideline |

|---|---|

| Definition of professionalism | Should be consistent throughout the institution and be prominently displayed and promoted. |

| Institutional support | Should be strong and publicly expressed. |

| Allocation of responsibility | Directors of curricula/courses should be highly respected, with clear and direct lines to senior administration and leadership. |

| The environment | Should be consistent with professional values and the institution’s mission statement. |

| The “cognitive” base (knowledge) | Should be explicitly taught at every level, including professional values, attributes, history, and the role of organizations. |

| Faculty development | All faculty should be educated in the content of professionalism and given strategies for how to teach and evaluate it in their own settings. |

Planning for a formal curriculum in professionalism begins with the end in mind: the description of the behaviors and responsibilities of a physician who is successfully living the values of professionalism in the workplace. Educators must then work to identify or develop a series of developmentally appropriate educational activities to move the learner from classroom learning (aspiring to be a professional) to simulated and early authentic workplace learning (acting as a professional) to successful workplace performance (being a professional).

The cognitive base of professionalism includes the enduring virtues, values, and behaviors of professionalism, the rationale for their existence, and the consequences to individuals and to the profession when lapses occur (Cruess & Cruess, 2009). Learners must be continuously reminded that the driving force for professionalism is our moral responsibility to our patients.

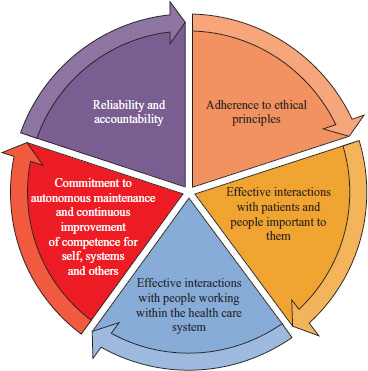

In addition to understanding professionalism values in the abstract, students must learn how these values are translated into behaviors. In a systematic review of the literature, Wilkinson, Wade, & Knock (2009) summarized thematic categories of behavioral competencies relevant to professionalism (Figure 9-3).

In addition to teachings in ethics and doctor-patient communication, lessons from social, behavioral, and engineering sciences can be used to ensure that the curriculum embraces the complexity of professionalism and prepares learners to face a multitude of different and challenging circumstances. Mindfulness training can help learners attend to their thoughts and emotions in the moment and to decrease likelihood that they will overreact to challenging professional situations (Epstein, 1999). Managing and communicating uncertainty can help physicians remain honest and avoid arrogance (Smith, White, & Arnold, 2013). Lessons on boundaries, commonly found in psychiatry programs but rare in other training environments, can be used to prepare students and residents to recognize and manage requests for inappropriate favors or relationships. Wellness awareness programs can remind learners and practicing physicians of the importance of attending to personal health and wellbeing as a requisite for sustaining energy and enthusiasm for high-quality patient care. Information from cognitive psychology and organizational development can help physicians-in-training learn about embedded cognitive biases and inferential thinking that explain how all people (including physicians and their patients) react in stressful situations (Senge, 2006; Croskerry, 2013). Leadership and change management instruction can help learners develop skills in leading, working within, and continuously improving the work of teams and systems. Conflict resolution skills can help physicians learn to navigate disagreements with peers, physicians from other disciplines, other professionals, patients, families, and administrators. “Crucial Conversations” training can provide physicians with tools to engage in difficult conversations in a respectful but direct manner (Patterson et al, 2002). Feedback skills can empower students and residents to engage in peer coaching when professionalismlapses occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree